American/TWA: the integration plan

June 2001

Airline mergers have been characterised by long–running industrial relations disputes, synergy targets that are never attained and major distractions to the management of the core business. The integration of TWA into American Airlines is probably the largest test case so far in the current game of airline consolidation. It will not be known for some time whether American Airlines’ management will pull off a successful integration, but presented below are the targets and objectives that have been set.

American agreed to purchase all of the assets of TWA, in conjunction with its Chapter 11 bankruptcy in January 2001. The initial task of the American management is to justify the cost of the transaction which is estimated at $2.8bn, consisting of $600m in cash and $2.2bn in assumed leases. Using standard financial ratios to compare this take–over to other airline transactions suggests that American would appear not to have overpaid for TWA.

The key to the success or otherwise of the transaction will be whether American can successfully integrate the selected assets that have been acquired. The benefits accruing to American are seen as:

- Increasing the scale and size of American’s network, particularly in the north east

- 138 leases on gates (by far the largest being the 57 gates at St. Louis)

- 171 slots at various constrained airports including 84 at New York JFK, 51 at New York LGA, 34 at DCA, and 2 at Chicago ORD

- 173 aircraft (153 on lease, 20 purchased)

- A third hub at St. Louis, to augment its existing Dallas and Chicago hubs

- Access to TWA’s substantial maintenance facilities in Kansas City, Los Angeles and St. Louis

- 18,000 line employees, many of whom have key skills in areas where there are national shortages

- 26% stake in Worldspan

Fleet

The fleet objectives for American are to minimise the number of fleet types and reduce aircraft ownership cost. Thus lease terms have been re–negotiated with lessors to reflect American’s higher credit rating, and for aircraft such as the DC–9s — which is an aircraft without a long–term future in American’s fleet plans — the length of the leases has been shortened.

The fleet purchased by American consists of:

- 9 767–300s, prioritised for short–term replacement as Pratt & Whitney powered, unlike American’s existing 767s which have GE engines.

- 27 757–200s, which again because of different engine types have had their leases shortened and will leave the fleet between 2004 and 2007.

- 15 717–200s, which as result of a re–negotiation of terms with Boeing will be added as a new type to the American fleet. In addition American has agreed to take 15 of the 35 717s that TWA had on order from Boeing, again under revised terms.

- 103 MD–80s, which are common to American’s existing fleet of MD–80s and will therefore be retained.

- 19 DC–9s, which will all be retired by 2003.

These acquisitions have had a knock on effect on American’s own fleet policy. American exercised its options on 15 767- 300s, which will replace the three–class A300s on transatlantic services, thus reducing a fleet type. The Airbuses will be used for American’s Caribbean services replacing both 757s and 737s, again reducing a fleet type. These aircraft, along with the 717s, will provide American with additional capacity in the US domestic arena.

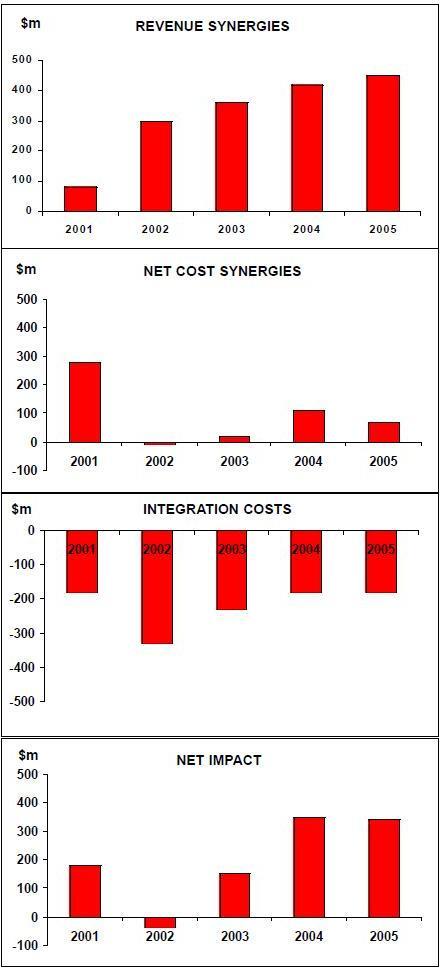

Revenue synergies

American has identified TWA’s lack of ability to generate strong revenues as a rectifiable problem. TWA’s revenue problems, according to American, stem from its single hub, limited number of corporate contracts, lack of alliance partners, weak FFP and the Karabu ticketing agreement. American has set itself a target of annual revenue synergies of $400–500m on a steady state basis.

The key synergy drivers are:

- Elimination of the Karabu ticketing agreement under which TWA was obliged to sell a proportion of its tickets at highly discounted rates to an agency owned by TWA’s former owner, Carl Icahn; this deal, part of Icahn’s settlement, was estimated to cost TWA $80- 100m a year lost revenue.

- Scheduling efficiencies — American has already announced a reduction in flying from San Juan, where the two airlines networks overlapped.

- Enhanced city presence, for example in Los Angeles where American’s market share will increase from 16% to 20%, which it is claimed, because of the "S–curve" effect, will result in an even larger increase in revenue share at the airport.

- Yield improvements through a greater share of premium traffic, the AAdvantage FFP and through improved alliance relationships. Adjusted for stage length and seat configuration, American estimates that TWA’s unit yield was 20% below that of American. It is forecast that "over time" this yield gap will close to 5–8%.

Cost synergies

American describes the cost impacts of the deal as a "mixed bag". On the negative side, as TWA’s employees are shifted onto American’s wage rates and work rules, the impact of these new contracts will cost American $260m a year.

Offsetting this increase American has identified over $150m of annual costs savings from areas such as:

- Elimination of duplicate overhead, which will be achieved in the short term in areas such as advertising, legal and finance, and in the longer term in areas such as computer systems maintenance and airport manning

- Reduction of facility rents which will also include better utilisation of gate facilities at airports such as Dallas DFW and New York LGA

- Improved purchasing; for example TWA had only 20% of its fuel purchasing under contract whereas American purchases some 70% under contract

- Implementing best practice in the area of fuel hedging.

Integration costs

To achieve both the revenue and costs synergies, American will be faced with what it hopes will be one–off integration costs. Whereas some of the synergy benefits accrue in the short–term, most take longer to achieve. Unfortunately in mergers, integration costs are normally up front and in the first three years of the merger will amount to some $600m. In this case the integration costs result from:

- Fleet modifications

- Facility integration

- Training

- System conversions

- Severance and relocation costs

The integration process

By American’s own admission the merger of the two airlines is "extraordinarily complex". American hopes to learn from the mistakes of the Air Canada/Canadian integration. It contends that it was a mistake for Air Canada to integrate Canadian’s schedules into its own before labour issues, customer loyalty programmes and computer systems had themselves been fully integrated.

So American has adopted a three–phase approach to integration.

Phase 1 — Transition of functions to American that have only minor labour and computer system impact, such as marketing functions (passenger sales, revenue management, scheduling and advertising) and financial functions (treasury, purchasing, and auditing). American expects that these functions will have been transferred by mid- July.

Phase 2 — Airport/Reservations integration. The two key drivers in this area are the airline marketing code (easy) and CRS host conversion (difficult). Both need to be achieved if reservation agents are not to face situations where they have incomplete passenger information. Converting TWA’s host system to American’s Sabre will involve solving four key issues:

- Providing the infrastructure for new Sabre hardware at each TWA airport.

- Achieving an interface between Sabre and TWA’s commercial systems controlling operations.

- Training TWA’s operational personnel, particularly airport and reservations agents.

- Providing Sabre/Worldspan interface software to allow a phased airport conversion.

Phase 3 — Operations integration. American expects that full operational integration will not be achieved until 2004–2005 The key is the ability to modify TWA’s aircraft to American’s specifications, and this in turn will determine the integration of TWA’s flight crew and maintenance functions.

On the marketing side American has already progress by offering reciprocal FFPs, extending American’s corporate and travel agency programmes to TWA flying and giving reciprocal airport club access. By the end of this year American hopes to have made progress in re–configuring the seating in TWA’s aircraft, standardising the in–flight product and co–locating at particularly hub airports.

Financial implications

Naturally, American suggest that the purchase of TWA will be earnings enhancing in the medium term. Initially it indicated that despite the up–front costs of integration that the deal would be earnings neutral in 2001. The deterioration in the US economy however has led American to be more cautious and is now talking about "some earnings risk in the near term".

Analysts and shareholders will require American to provide detailed analysis as to how progress is being made with the integration and whether targets are being met. The problem for all parties will be what to measure and how to measure it. Airline mergers are very complex, and as integration progresses measurement of benefits and synergies becomes ever harder. Cynically, one might argue that as long as the management team at American that made the TWA acquisition remain in place then it is likely that numbers will be provided that prove that the acquisition was the right strategic move.