Eastern adaptations of the Western LCC model

October 2004

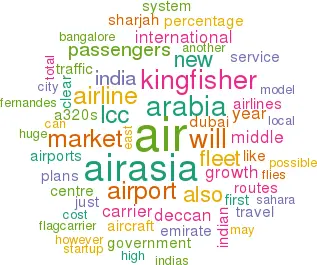

The LCC model is working in the Asian context as evidenced by the rapid growth of Malaysia–based AirAsia, the emergence of Air Arabia in the Middle East market and the ambitious plans of Air Deccan, Kingfisher and others in the Indian market. The most basic question facing these LCCs is how to adapt US/European models to local conditions.

AirAsia

For AirAsia in Malaysia, the core strategy is clear: stick as closely as possible to the Ryanair model, using high–density 737–300s, high aircraft and personnel utilisation, secondary airports where possible, rigorous cost control, very aggressive pricing (including promotional fares at less than 1 Ringitt or 25 US cents), internet–based distribution, and high profile marketing featuring the media–friendly chief executive, Tony Fernandes.

This does not mean that there are not major obstacles to LCC development in Southeast Asia.

As Tony Fernandes points out, the airports, initially at least, hate AirAsia, many local politicians and regulators still regard the airline with deep suspicion, and traditional full–service competitors don’t have to worry about niceties like antitrust legislation.

AirAsia’s main base is at the new Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA), which is not only expensive but also further from the city centre than the old Subang airport. The airline would love to relocate to Subang, and Fernandes is lobbying the government to this effect. The government, however, still seems to prefer the option of an LCC–dedicated terminal at KLIA.

The airport strategy is imaginative. For example, AirAsia uses Senai airport just across the Malay/Singaporean border as its alternative to Changi (though the Singaporean authorities have so far blocked a bus service from Senai to the Singapore city centre).

AirAsia flies to Macau airport although the large majority of passengers are actually travelling to/from Hong Kong.

Cost–conscious passengers are clearly not deterred by the ferry trip between the two ports.

International expansion will almost certainly come though more franchise deals, enabling it to developed from new bases in Southeast Asia, maybe the Indian subcontinent and eventually China. Early this year, the carrier set up Thai AirAsia in Bangkok, in which it holds a 49% stake. Thai AirAsia operates domestically within Thailand and internationally to Macau, Malaysia and Singapore.Acceptance of AirAsia by those in power follows traffic trends — AirAsia is on schedule to carry 3m passengers this year.

Vested interests can be mollified by pointing to the fact that almost all of AirAsia’s growth appears to have come from stimulated traffic rather than stealing from the flag carrier MAS, which has also grown in recent years. Airports can be made to appreciate that volume growth can be guaranteed by AirAsia and persuaded to concede on landing fees.

Security forces have to be educated about ticket–less travel in places where travellers have previously been unable to get into terminals without the correct travel documentation.

Investors see in AirAsia the possibility of a Ryanair–type growth in revenue and profits and so in valuation. An IPO on the Kuala Lumpur stock exchange is planned for late November, which will see about 30% of the airline floated at around 1.40 Ringgit ($0.37) a share, which should raise between $230 and $310m, according to local analysts' estimates.

The total value of AirAsia therefore is being put at about $900m. This compares to Ryanair’s current stock–market valuation of just over $4bn. Ryanair has a fleet of 71 737s (57 -800s and 14 -200s) with 98 737–800s on firm order. AirAsia intends to use the funds from the IPO to finance an order for at 50+50 737–800s or possibly A320s, to supplement and replace its current fleet of 20 737–300s.

Air Arabia

Air Arabia has pursued more of an easyJet approach. Based in the Emirate of Sharjah, which is the Emirate just north of Dubai, all its 14 routes are by definition international.

It flies to main city airports (there generally being no secondary alternatives) and pays rack rates and expensive ground handling charges (there being no choice), but Sharjah Airport is a key asset. Located just 30 minutes away from the centre of Dubai, not much further than Dubai international, Sharjah Airport is uncongested and low cost, as Sharjah Airport Authority owns 60% of Air Arabia.

Air Arabia is unique in being the first flag carrier to have been designed on clear LCC principles — in terms of its point–to–point network, its aircraft utilisation, its crewing ratios, its internet–based distribution, its simple pricing structure and yield management system, its standardised A320 fleet, its slim management structure and its outsourcing of the maintenance function to GAMCO.

Adel Ali, the CEO, is also a media–friendly personality.

In its first year of operation (to November) Air Arabia will have carried about 0.5m passengers at an average load factor of 77%, which is well above budget (Aviation Economics was responsible for the business planning for the airline which went from concept to first flight in eight months).

It is clear that there is strong demand for budget air travel within the Middle East from various sources — Middle Eastern and expat leisure travellers attracted by Dubai, cost–conscious businessmen, students, migrant workers, etc. — which Air Arabia is managing to fulfil.

It is an intelligent flag–carrier for the Emirate, which has limited oil reserves — in contrast to the new flag–carrier of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, Etihad, which appears to be aiming for global A380 dominance, replicating the full–service, long–haul models of Emirates, Gulf Air and Qatar Airways.

However, Air Arabia does face constraints on its growth, related to the bilateral regimes of the region. Most of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries adhere in theory to an open skies regime, which means that there should be no barriers to expansion on services to Qatar, Bahrain and Muscat.

Lebanon also has a liberal regime. But countries like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, also GCC members, stick to restrictive, traditional air service agreements with frequency and capacity caps. Sri Lanka stipulates minimum turn–around times of 90 minutes at Colombo (Air Arabia mitigates this by scheduling Sharjah–Colombo flights during the night).

Rights to India, a potentially huge market, have not yet been granted. The airline currently cannot get into Jordan, another important market.

As with AirAsia, Air Arabia’s approach is to grow wherever possible, in the process proving the attractiveness of the LCC product to the Middle East market. The regulatory barriers are frustrating but eventually they will be lowered.

Investors, meanwhile, are starting to look at the carrier with interest, and a fundraising exercise may well be need in the next few years as the carrier expands with new A320s.

Air Deccan and Kingfisher

India should be the next big LCC market.

The country’s middle class is variously estimated at 150–200m out of a total population of over one billion yet domestic air travel is anaemic — this year total domestic traffic will be about 15m passengers, and a large percentage of those will be connecting to international flights.

With the major population centres (Mumbai, Delhi, Bangalore, etc) located 1.15–1.30 hrs flight time apart, and with a slow and overloaded rail system (which nevertheless manages to transport 15m passengers a day), the market would seem ripe for LCC entrants.

Currently the market is divided up among three full service, interlining carriers — Indian Airlines, Jet Airways and Sahara — but there are also new entrants — Air Deccan and Kingfisher.

Air Deccan is based at Bangalore, the centre of India’s booming IT industry, which attracts young, relatively affluent workers from all over the subcontinent. Air Deccan’s mission is to link the regions and it has done this recently with a fleet of six ATR 42s.

However, this August it leased three A320s from SALE, the first of which is now operating Bangalore–Delhi. Its fleet plans include another two A320s and another 15 ATR 72s.

Kingfisher is a start–up with clear ambitions — its fleet plans call for 12 A320s by the end of 2005, and it has already committed to four new aircraft from GECAS. Although its headquarters are in Bangalore, its base will probably be Mumbai. Kingfisher is flirting with frills like IFE on its aircraft and will cooperate with Indian Airlines in several areas, outsourcing maintenance to the flag–carrier and apparently sharing some check–in facilities.

This new airline is part of the whole Kingfisher lifestyle concept. Kingfisher beer is India’s leading brand (and has a following in the UK) but direct advertising of alcohol is prohibited in India. So the Kingfisher Group has created a lifestyle brand by, for example, sponsoring Bollywood movies, and the airline will be designed to be compatible with the marketing message. Sahara Airlines has a similar role — it is a highly visible symbol of the huge Sahara micro–banking empire in India, which specialises in small–scale loans and saving accounts.

So it could be argued that neither Kingfisher nor Air Deccan (because of its split fleet) is a pure LCC start–up. There are other plans for Ryanair–type airlines, which one might think would be ideal for India, but these may or may not materialise.

The downside of India’s huge demand potential is its bureaucracy and regulation. Start–up carriers have to negotiate the traffic allocation rules, whereby if an airline flies a metro route like Delhi–Mumbai, it has to allocate a certain percentage of the metro ASKs on other inter–state routes and a further percentage on regional routes in the northeast and a further percentage on intra–regional routes. Earlier this year a government commission recommended the replacement of this absurd system with a Public Service Obligation subsidy system, but since then the government has changed, with the Congress Party unexpectedly gaining power. There is also the excessively high price of jet fuel in India and the restoration of an import tax, which could add 48% to the cost of operating lease rentals.