Can Ryanair stick to the winning formula?

November 2005

Ryanair is the most profitable carrier in the world and now aims to become Europe’s largest airline by 2012, carrying more than 70m passengers a year. Can the Ryanair success story continue, or will the dash for growth tempt management to alter a winning strategy?

The airline’s philosophy is summed up by the quote from Michael O'Leary, Ryanair CEO, that: "Our strategy is like Wal–Mart — we pile it high and sell it cheap." But it didn’t start out that way. Ryanair was set up by the Ryan family in 1985 as a conventional airline with turboprop aircraft and 25 staff. But by the end of the decade, despite the introduction of jet aircraft, the building up of a network between Ireland and the UK, and attempts to launch an FFP and a business class service, Ryanair had accumulated €30m in losses in the face of fierce competition from Aer Lingus and British Airways.

It was time for a radical change. In 1991 the Ryan family refocused on Ryanair, following the failure to effect a stock–market flotation of their mega–lessor GPA, and its subsequent collapse.

€30m was invested and the airline was relaunched with new management as Europe’s first LCC, copying the strategy of Southwest Airlines. Against competitors that struggled to match the lower fares of Ryanair, the new direction proved effective almost immediately. Through the early 1990s the airline’s low fare, low cost strategy became even more successful, particularly after the introduction of 737s.

In May 1997 Ryanair floated on both the NASDAQ and Dublin exchanges, with David Bonderman replacing Tony Ryan as chairman..

The shares were more than 20 times oversubscribed and on the first day of trading the share price rose from €11 to more than €25. Revenue growth was given a major boost in 2000 by the launch of a booking website that today receives 15m unique visitors per month and accounts for 98% of all bookings (the other 2% come via the telephone). Even in the financial year covering September 11 Ryanair’s net margin was 24%, and in fact margin has never fallen below 20% at any time during the 2000s.

Today, Ryanair’s staff of just 2,760 operate more than 260 routes to 21 countries out of 15 European bases: Dublin, Shannon, Cork, London Stansted, London Luton, Glasgow Prestwick, East Midlands, Liverpool, Stockholm Skavsta, Frankfurt Hahn, Milan Orio al Serio, Brussels Charleroi, Pisa (Florence), Rome Ciampino and Girona.

These are bases rather than hubs, as Ryanair’s aircraft operate on a basic point–to–point roster, with an average 25–minute turnaround time. Ryanair’s first continental base was opened only in 2001 — at Brussels Charleroi — but the airline has been accelerating its base launches ever since. In the last 12 months bases have opened at Pisa, East Midlands and Liverpool (where easyJet also has a base), while the 15th base was opened at Cork in October 2005, where Ryanair is pressing the airport authority to allow the airline to use the existing terminal exclusively for low cost carriers once a new €160m terminal is opened later this year. Shannon was also developed into a base in May 2005, with 16 routes currently available throughout Europe, although this summer O'Leary admitted that "yields continue to be slightly lower than expected" at Shannon.

737 frenzy

The airline currently operates a fleet of 83 737- 800s and nine 737–200s, although the 737–200s will be phased out by the end of 2005 as a massive 156 737–800s are on order. 70 of these were ordered in February, for delivery between 2006 and 2011, while in October Ryanair converted nine of its options into firm orders, all for delivery in late 2007. Ryanair’s fleet will grow to 200 by 2010 and 234 by 2012, even assuming it does not convert any of its outstanding options.

The 737–800 orders are crucial to Ryanair, as the aircraft have an operating cost per seat some 50% less than the 737–200. In addition, 737–800 winglets will start being installed on all aircraft from December this year, and these will save an estimated €96,000 in fuel burn per aircraft per year. For all its 737–800s, the airline is paying considerably less than Boeing’s list price of $61m- $70m per aircraft. A "baseline price" of €51m has been mentioned by Ryanair, plus another $1m per aircraft for its required internal fittings. But Ryanair also negotiated what it calls an extra "price concession" on this baseline figure, consisting of credits towards Boeing services and products, as well as "allowances" for promotional activities. These are nothing more than a further price discount by Boeing, bringing the cost per 737–800 to probably around €30m for Ryanair.

Approximately 20% of the new aircraft will be acquired on operating lease, in order to retain operational flexibility and to secure financing benefits. Additionally, Ryanair is financing part of the order through bank loans guaranteed by the Export–Import Bank of the US, which in effect gives the airline a subsidy from the US taxpayer, thereby sweetening the deal even further.

Base doubling

The aircraft will enable Ryanair to achieve its ambitious growth plan of doubling passengers carried to 70m by 2012. This also means more than doubling the amount of bases that Ryanair operates, to approximately 35 by 2012. With just two further bases scheduled to open by the end of 2006, that means around three or four will have to open each year over the 2007–2011 period.

These will be chosen from a shortlist of 48 airports that Ryanair has identified as potential bases throughout Europe. Of these, 10 are in France, eight in Spain, seven in the UK and Ireland, six in both Italy and Scandinavia, four in Germany and seven others elsewhere on the continent.

One of the two new bases for 2006 is likely to be in Germany, where Ryanair has just the one base so far — Frankfurt Hahn, which it launched in 2001. Four airports were under consideration: Berlin, Cologne, Munich and Hamburg Lubeck, but the latter appears to have fallen off the shortlist after plans to develop it into a gateway base for northern Germany were shelved following a local court decision that prohibited an extension of the runway and associated infrastructure. Ryanair’s plans for Lubeck had in any case sparked fury from German airlines, seven of which attempted to sue Lubeck airport for what they claimed were unfair and illegal subsidies paid to Ryanair since 2000.

However, the setback at Lubeck reveals just how flexible Ryanair’s route strategy is, because it claims that as a direct result of cancelling its plans for the German airport it will instead launch 10 new routes out of East Midlands in March 2006 (adding to five existing services). These services will temporarily reinforce the UK’s position as Ryanair’s most important market for originating traffic, currently accounting for 41% of passengers flown. Just under half of all Ryanair’s aircraft are based at London airports (although traffic was only slightly affected by the London bombings over the summer). However, the long–term trend is for the UK’s percentage to fall as more continental European bases become established. Currently Germany is the second most important originating market, accounting for 13% of passengers, with Italy and Ireland a close third, each with 11%.

In a recent statement O’Leary has outlined long–term expansion plans for Ryanair’s operations at Frankfurt Hahn. It seems as if Hahn is now set to overtake Dublin as Ryanair’s second base. Ryanair already has 6 aircraft based at Hahn, operating 26 routes. By 2012, it plans to base 18 aircraft flying over 50 routes at Hahn. According to O’Leary “Ryanair is committed to an investment of $1bn in new aircraft at Frankfurt Hahn”. Ryanair is also providing a loan of €12.5m ($15m) in respect of 50% of the total capital expenditure on the new passenger terminal and will also locate a Ryanair maintenance facility at the airport.

Italy is likely to jump into second place following the Lubeck decision and the launch of a third Italian base — Pisa — in October this year. Ten routes are being run out of Pisa, with two aircraft based at the airport initially. Ryanair also has five aircraft based at Rome Ciampino and four at Bergamo, and it is challenging Alitalia even harder by launching domestic Italian routes this year, all out of Rome. In 2005 Ryanair expects to carry more than 10m passengers on 66 routes to and within Italy.

Cost pressure?

But outside of these major markets, where else will Ryanair expand to, and — more importantly — as the new 737–800s are delivered, will it keep rigidly to its low cost strategy, in which rock–bottom airport costs are such a key component? Ryanair vows it will not start up operations anywhere unless airport charges are low enough.

Given that Ryanair has a list of 48 airports from which it needs to pick 18 new bases — and that the airline appears more than willing to walk away from an airport if the terms are not right — then the airline’s route/base selection strategy is one of playing airport authorities off against each other, with contracts signed only with those that are willing to offer the very lowest charges and/or the highest subsidies.

For example, one potential base under consideration is Malta, at which Ryanair would station up to six aircraft and link the island to more than 25 destinations across Europe, carrying as many as 2m passengers a year by the end of the decade (and which would lengthen the airline’s overall average sector length). However, Ryanair is making it clear it will not do so until Malta’s current €25 per passenger departure charge (which includes an airport charge, government security fee and handling costs) is reduced to at least €10 and preferably around the €7.50 mark.

Ryanair is also ruthless in its approach to any threat of additional cost on existing routes. For example, this November it cut its Stansted- Newquay service from two to one flight a day after the local council introduced a £5 "airport development fee" on passenger tickets in October. The average fare on all Ryanair flights is around £28, and many of its regional routes are extremely price–sensitive. Of course Ryanair may also be victim of its own success — at Newquay, the council says its needs to spend £2.8m developing the airport due to the influx in passengers that Ryanair has brought.

Ryanair is also not afraid to drop routes — for example this year routes between London Stansted and Erfurt (Germany), and between Girona and Turin were halted after no more than 12 months' operation each. Ryanair’s policy on each new route is to offer fares that quickly build a load factor of at least 80%, and then to build up yield while maintaining that minimum load factor. If that is not achieved within a relatively short period of time, the route will be axed.

One area of expansion that fits the low cost requirement is central and eastern Europe. Until this year Ryanair insisted that eastern Europe was not a priority for the airline, and instead it concentrated on western and central Europe. That view is now changing. Ryanair opened a route from London Stansted to Kaunas (100km from Vilnius) this autumn, becoming the first LCC to serve Lithuania after the government invited eight LCCs across Europe to commence operations. Ryanair also operates five routes to Latvia, 13 to Poland, one to the Czech Republic and three to Slovakia (Bratislava, which Ryanair uses as its "Vienna" airport). All but seven of Ryanair’s eastern European routes go to London Stansted or Frankfurt Hahn, which indicates the importance of the German base for further routes to the east. O'Leary now wants the EU to liberalise air travel to eastern Europe and to sweep away existing bilaterals, which he deems restrictive. If that happens, Ryanair’s average sector length — which has already risen by 10% in 2004/05 — will increase further. Nevertheless, while bases may be opened in central and eastern Europe towards the end of the planned expansion period, Ryanair’s main base focus for the next few years will remain western Europe, where it believes there is still lots of untapped potential.

How Ryanair’s base strategy will be influenced by the European Commission’s guidelines (published in September) as to how much aid state–owned regional airports can give to LCCs is yet to be seen. Naturally, O'Leary describes the Commission’s move as a "blunder", but it was hardly a surprise given its 2004 ruling that Ryanair had to repay millions of Euros of illegal subsidies at Charleroi airport to the Walloon regional government (on which the airline is appealing to the European Court of Justice).

What’s likely to happen is that Ryanair will continue to reap subsidies and incentives from airports wherever and whenever it can, unless or until local courts intervene. A typical Ryanair deal was laid bare in April year when, controversially (at least in Spain), a London Stansted–Santiago de Compostela service was launched after the local authorities agreed to pay the airline €3.8m over the four years to 2008. The money is coming from the local tourist board in order to support Ryanair’s marketing of the destination, but predictably this caused criticism from Iberia, which operates from Santiago de Compostela to London Heathrow.

Equally predictably, Ryanair ignored the furore and added routes from Compostela to Rome Ciampino and Frankfurt Hahn this October. If Ryanair does stick to its existing mantra of picking bases that offer either subsidies and/or very low charges per passenger, then it’s unlikely that the airline will enter many primary airports, which is what the mainline airlines fear. Now and again a primary airport may be willing to sign an appropriate deal (from Ryanair’s point of view), but what has been admirable about Ryanair’s strategy so far is that it has consistently stuck to its strategy of low–cost airports, with the exception of London Gatwick, out of which it operates just four routes, all to Ireland. And at Rome, although Ryanair pays the same "rack rate" as other airlines, it has negotiated a deal on handling.

Financial trends

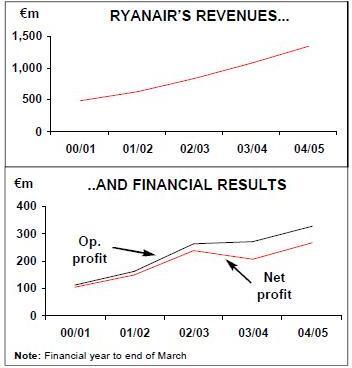

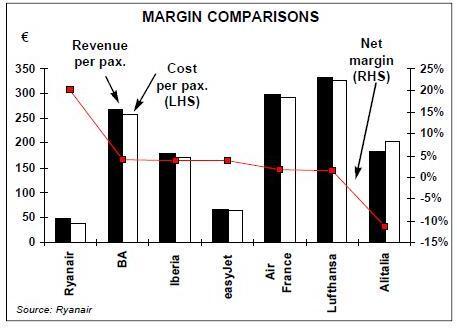

Management insists it will not go down the easyJet route, which operates to higher cost, primary airports such as Amsterdam Schiphol, Madrid Barajas, Paris CDG and Milan Linate. In the 2004/05 financial year (ending March 31st), Ryanair reported an operating profit (before exceptionals and goodwill) of €329m, compared with €271m in 2003/04, and a net profit of €267m, compared with €207m the year before. This was based on a substantial 24% rise in operating revenue, to €1.3bn, and a 19% rise in passengers carried, to 27.6m. And, according to an analysis by the Irish Independent in October, last year Ryanair made €39m from airport charges and taxes paid in advance by passengers who failed to show up for flights (as Ryanair’s policy is not to refund these charges for no–shows).

Contrary to the O'Leary’s predictions a year earlier of massive fare wars and a bloodbath among LCCs, Ryanair’s yield over the 12 month period actually rose by 2%, despite a 16% increase in capacity (although in 2003/04 yield had fallen by 14% compared with the year before). Ryanair says many of Europe’s flag carriers reduce capacity after going head–to–head with Ryanair — which is exactly what the LCC wants, and is a trend that will continue as flag carriers increase long–haul capacity and cut back loss–making short–haul.

However, costs rose by 25% in 2004/05, with a 50% rise in fuel costs to €265m. That trend continued into the first half of the 2005/06 financial year (April–September 2005), when Ryanair posted a 20% increase in operating profit, to €282m, and a 20% rise in net profit, to €242m (the first figure excludes a one–off aircraft insurance settlement of €6m). Revenue increased by 33% in the half–year, to €946m, and revenue per passenger rose by 3%, thanks mainly to ancillary sales.

Passenger traffic grew by 29%, to 18m, with load factor of 86%, while yield rose by 3% despite a29% rise in capacity. For the half–year Ryanair had a healthy net margin of 25% (although 3% lower than in 1H 2004/05).

Ryanair attributes the yield rise to the imposition of fuel surcharges by its rivals, which makes the comparative fare gap even wider. Ryanair has a policy of not introducing fuel surcharges (although it is simple enough to compensate for fuel price rises by adjusting fares upwards), and O'Leary is critical of airlines that do impose surcharges despite the fact that they hedge most of their fuel costs, calling it "profiteering at passengers' expense". However, O'Leary also believes competitors will have to reduce underlying fares through the rest of this year if the gap appears too big to customers.

But that’s putting a positive gloss to a situation where, in the first half of 2005/06, Ryanair’s fuel cost more than doubled, to €237m, making fuel account for 36% of all operating costs in the period, compared with 24% in 1H 2004/05. And this was despite a major effort by the airline to reduce costs in other areas to compensate. Excluding fuel, Ryanair’s unit costs fell by 7% in the period.

Although part of the fuel cost increase was due to increased capacity, the concern that Ryanair (along with all other airlines) has for fuel is obvious, and is a major contributor to its cautious outlook for the rest of the year — although it also believes the European market is not as competitive as it was a year ago, with less fare discounting around.

According to Irish stockbroker Merrion, each $1 per barrel move in the price of oil has a 2% impact on Ryanair’s 2005/06 earnings. However, it is possible to be too critical here, since Ryanair faces the same problem as every other airline with regards to fuel, and is probably in the best position of all to absorb the rising cost. Ryanair is believed to have hedged almost all its winter fuel needs (to the end of March 2006) at a price of $49 per barrel or lower, and it will continue to hedge ahead the vast majority of its fuel needs. Indeed Ryanair also sees a positive side to rising fuel prices in that it may tip over the edge into bankruptcy some of the more marginal carriers across the continent.

Looking to the rest of 2005/06, Ryanair believes that rising fuel prices will be offset by cost reductions elsewhere — most particularly in aircraft (through the newer models) and airports (via deals with airport authorities etc) — although yield may fall. That’s worrying since Merrion calculates that "each 1% variance in yield impacts 2005/06 earnings by 4%" and comes despite Ryanair’s attempts — as one analyst puts it — at "selling fewer seats at the lower end of its fare range".

For the full financial year, Ryanair expects to post underlying net profit of around €295m, around 10% up on 2004/05. Load factors are forecast by Ryanair to be around the 83% level for the full 2005/06 financial year — already this year load factor is consistently above 80%, and it reached 90% over the summer months.

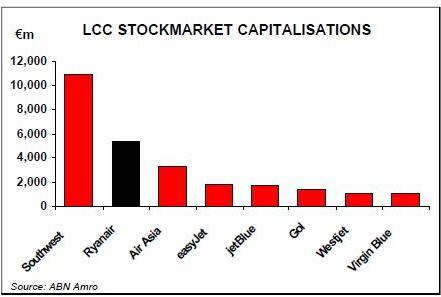

Ryanair’s market cap of more than €5bn is three times larger than easyJet’s, even though easyJet has a bigger turnover and fleet. However, interestingly, this summer ABN Amro stated that "our preference for easyJet is based on our core view that over the coming five years easyJet’s margins will improve from current low levels whilst Ryanair’s will decline. We expect Ryanair’s margins to remain way above easyJet’s, but the gap to close."

O'Leary factor

O'Leary clearly plays up to his persona and doesn’t care if people don’t like him, his aggressive approach to business combined with an antiestablishment persona may be beginning to have a negative effect on the long–term future of Ryanair. Ryanair’s customers can clearly go elsewhere if they do not like the frugality of the airline’s product and service (whether it’s an absence of window blinds or a maximum of 15kg in free checked–in luggage), but for the airline’s workforce it is a different matter, because if a substantial minority of staff are concerned about Ryanair’s management style then this can directly impact on customer experience, and hence the success of the airline.

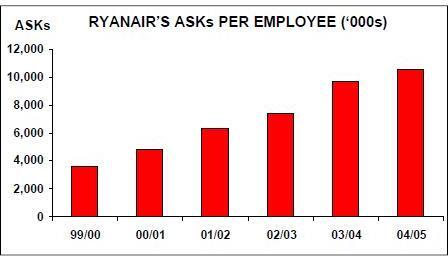

Naturally, cutting labour costs is core to the LCC strategy. 50% of payroll cost is productivity based, and staff have to pay for their own uniforms, crew meals and even training. They are also not given sick pay during their probationary period. There’s no denying that Ryanair is lean. Of the 2,700 staff, just under 2,000 are pilots or cabin crew, and productivity as measured by ASKs per employee is impressive (see chart, below). But it is one thing to cut labour costs and another to instil a working environment where a minority of staff are — apparently — genuinely unhappy. It is reported that Ryanair is having to recruit staff from eastern Europe to make up staff shortfalls, but it’s the refusal to recognise trade unions that has caused the greatest controversy.

In May Ryanair refused to give a salary increase to Dublin–based pilots that did not want to bargain individually with management. Allegedly, Ryanair wants 737–200 pilots who retrain for 737–800s to pay a €15,000 bond, and if they don’t pay such a bond they will be made redundant when the 737–200s are phased out.

Ryanair’s management has set up Employee Representative Committees (ERCs) and a European Works Council. Nevertheless, in October the Irish High Court ruled that it would allow a Labour Court to formally investigate the ongoing dispute between the airline and the Dublin pilots — a decision that, naturally, Ryanair is appealing.

A website set up in 2004 by the International Transport Workers' Federation for employees to post their opinions on the airline — www.ryan–be fair.org — has been swamped by alleged tales of bullying management and rock–bottom staff morale (although there are also a few positive comments). Even more annoying to Ryanair is www.repaweb.org, a site for the "Ryanair European Pilots Association" and associated with BALPA, IALPA and ECA — three pilot unions/associations.

This allows Ryanair pilots to communicate with each other and "freely express their views " on a range of issues. Earlier this year Ryanair launched legal proceedings against Irishbased IALPA, whom it says carried out an "organised campaign of harassment and intimidation" via the site.

As for Ryanair’s external image, the airline’s aggressive attitude had led to more than one PR disaster. In April, for example, Ryanair banned its staff from recharging their mobile phones, which it believes is the equivalent of stealing electricity. But even if every single member of Ryanair’s staff recharged their mobile phones fully once a week, this move will save the airline an estimated €2,000 per year in total. For that €2,000 saving, Ryanair achieved acres of bad publicity in the press.

Even more damaging, in December 2004 Ryanair lost its appeal against a UK court judgement that it must provide free wheelchairs for disabled passengers at airports Ryanair argued that the cost of doing should be born by the airport operator, BAA and, in a reaction to the initial judgement added a 35 pence surcharge to UK tickets to recover the cost — again, a move that resulted in substantial adverse publicity. The surcharge has since been reduced by 50%, as Ryanair will now share the cost of wheelchairs with BAA.

On a whole host of other issues, Ryanair is happy to take on anyone and anybody that stands in its way, whatever the adverse effects on its image. In 2005 this has included:

- A French court ordering Pau airport to redraft its contract with Ryanair after declaring that the town’s Chamber of Commerce had given illegal subsidies to the airline.

- A Belgian industrial tribunal finding Ryanair guilty of illegally terminating the employment of three cabin crew at Brussels Charleroi, who were protected by Belgium laws even though the airline argued they had signed contracts drawn up in Ireland.

- The UK CAA investigating whether Ryanair is ignoring the new European rules that require airlines to look after customers if flights are delayed by more than two hours. Ryanair is arguing that it should not have to pay for delays that are out of its control, and that it should not have to offer meals to delayed passengers since it does not offer meals on board.

Ryanair is appealing or contesting many of these decisions — the Charleroi hearing will be held in the summer of 2006, while the European Low Fares Airline Association is strongly contesting the passenger compensation rules — but accompanying comments from O'Leary on these issues results in a steady erosion of goodwill from press and, more importantly, from staff, customers and suppliers.

This can have serious consequences. For example, it’s fair to say that Ryanair has a poor relationship with BAA, the UK airport operator, which deteriorated over BAA’s intention to increase the fuel levy at London Stansted. Ryanair claimed the increased charge would cost it more than €1.6m a year, and so withheld €1.5m of payments on outstanding invoices to BAA as a protest. An out–of–court settlement was reached in April 2005, in which BAA reduced the fuel levy by 39% for all airlines at London Stansted until 2008, and Ryanair agreed to pay its outstanding bills.

However, the row was not ideal given that the airport is Ryanair’s most important base (with more than 80 routes) and that the airline’s current agreement on landing charges is shortly to be renegotiated, given that it expires in March 2007. BAA is likely to want a substantial increase in charges to pay for the €5bn–plus development of the airport, which O'Leary describes as "grandiose" and "gold plating on a rip–off scale", and which Ryanair claims should cost no more than €600m for a second runway and terminal. Ryanair’s other motivation here is that it may be trying to protect its position at Stansted, as greater airport capacity reduces its scope for dominating the routes from there. Perhaps that is why Ryanair has invested around €200m in developing its base at London Luton, which currently operates 12 routes, but which is also the main base for easyJet. (easyJet is increasingly a rival for Ryanair — 16% of Ryanair’s routes on a city–pair basis overlap with easyJet.)

Ryanair is also unhappy at the Irish government’s plan to build a second terminal at Dublin airport, to be built by the Dublin Airport Authority (DAA) as part of €1.2bn project to increase capacity from 18m passengers a year to 30m by 2016. Ryanair is taking the government to court, claiming that the project was not put out to open tender. Ryanair’s objection is not to the development — since O'Leary condemns "inadequate facilities and long queues" at the airport — but that the development should be strictly cost–controlled in order to avoid further rises in airport passenger charges. Already a 22% rise in fees is to be introduced in January 2006, although the DAA had wanted to increase fees by 50%. Ryanair had previously said it would station another 20 aircraft at Dublin once a second terminal was built. One analyst believes Ryanair’s behaviour on Dublin airport has been affected by a personal feud between O'Leary and Bertie Ahern, the Irish Taoiseach.

O'Leary has gradually but steadily sold his stake in Ryanair. Prior to the 1997 IPO he held 17.9%, but has since made close to €200m by reducing his stake to 4.6%. At some point in the not–too–distant future O'Leary may leave the airline (speculative stories are already appearing in the press), and it’s an arguable point whether his departure would have anything like the impact of, for example, Branson leaving the Virgin empire.

Ancillary key

Although Ryanair’s policy is to push up yields on established routes (particularly where there is a lack of competition), a substantial rise in revenue though fare increases is not possible under its LCC model. And that’s why increasing ancillary revenue to existing passengers is just as key to the airline’s continuing success as is generating new routes and passengers.

The trend is clear — in 2004/05 scheduled passenger revenue rose by 22%, to €1.13bn, while revenue from other sources rose 40%, to €209m. If those comparative rates of increase continue, then ancillary sales will overtake passenger revenues within a decade. Interestingly, Merrion calculates that a 5% increase in ancillary revenue translates to a 3% rise in earnings, so this is a high–margin stream, primarily because Ryanair provides little of the ancillary products and services itself, instead earning commission from third–party suppliers.

Strategically, the ancillary push is correct, even it’s not where Ryanair’s core competence lies. According to Ryanair, its average fare per passenger is €41, compared with €62 at easyJet and €268 at BA, but its overall revenue per passenger is about €48 and its operating profit about €12. In August this year ABN Amro stated that it saw Ryanair’s shares (then €6.80, the same level as they were as at the start of November) "at the top of its trading range … it is hard to see how the revenue side of the business could improve". In October it said that "we retain our long–held view that the company’s margins will deteriorate [to less than 20%] over time as a result of increased airport charges, marketing and labour costs … we continue to believe Ryanair will at some stage in the future face unionisation."

Indeed in this context some analysts now see Ryanair almost as a retail company, rather than an airline, and the analogy is interesting. Presumably at some point the number of profitable European routes than Ryanair can service will reach saturation point, and then the focus of revenue growth will switch primarily to ancillary sales. On the Ryanair website passengers can book lounges, parking, hotels, insurance and holidays, as well as purchase loans and credit cards, while other revenue comes from items as diverse as scratch cards and aircraft advertising. On the latter, in September the airline announced a two–year contract with Inflight Media that will allow companies to advertise their corporate livery on Ryanair’s fleet.

Financial services is likely to be a key area of expansion for Ryanair over the next few years, as well as gambling, which O'Leary describes as the "mother load". This will stretch the brand away from travel, although not to the extent of Stelios Haji–Ioannou and the "easy" franchises. It is a theme that O'Leary increasingly espouses, and indeed in September this year he speculated that within 10 years the standard airline business model could be entirely free flights, with profits coming from ancillary sales and a cut to airlines from airport retailers.

But it doesn’t always work out as planned. Earlier this year Ryanair abandoned the testing of an in–flight entertainment system for films and video that it launched six months' earlier after finding that not enough passengers were willing to pay the €7 fee per flight. O'Leary had predicted it would make "enormous sums of money".

Clearly while Ryanair’s management are experts in transporting passengers by air, they have less experience in selling other good and services, and analysts will watch the figures closely over the next year or so to see if the drive to further ancillary revenue is truly successful.

Never-ending success?

In August — for the first time — Ryanair carried more passengers on its European network than BA worldwide, and although this was partly due to the industrial action at BA over Gate Gourmet, a permanent overtaking must surely be a matter of time given Ryanair’s ambitious expansion plans.

Although growth inevitably results in some dis–economies of scale (such as more complex scheduling), analyst concerns about the pace of route and base expansion are unjustified, and the helter–skelter pace of launches will continue. 80 of Ryanair’s 227 routes as at the end of September had been launched in the last 12 months, with 40 more planned in six month period October 2005 — March 2006.

What is key during expansion is that Ryanair sticks to its core philosophy, as summed up in a presentation to investors in October, that "the lowest cost wins — in every market". That’s what Ryanair management excels at, and they will continue to resist anything and everything that adds to the cost of a ticket, from whatever the source. For example, Ryanair lobbied hard when the UK government considered a recommendation from the UK CAA that a £1 levy be imposed on air tickets in order to modernise the system for protecting air travellers against a company’s collapse (the system is currently based on bonds paid to the CAA by firms). According to O'Leary, "it is wrong for ordinary passengers booking on successful airlines like Ryanair to be asked to subsidise passengers booking with financially flaky airlines and tour operators, because the CAA is not doing its job correctly." To Ryanair’s relief, the government rejected the CAA’s proposal in October.

That cost control is vital in an environment of rising fuel prices but, as discussed earlier, even more important are the strides that Ryanair is making in ancillary revenue. The other potential problem is distraction from non–organic growth.

Ryanair’s cash pile rose to an impressive €1.8bn as at the end of the first half of the 200/06 financial year (September 30th), and although Ryanair insists that growth will come from new routes and bases, it has not ruled out "possible acquisitions that may become available in the future". With a large and growing cash pile, would Ryanair be able to resist the temptation of, for example, a suitable airline in eastern Europe? That’s not to say such a move would be wrong, but that it would impose a huge strain on management’s workload, and undoubtedly lessen the focus on organic growth and the crucial ancillary sales.

Some analysts are intrigued by recent comments made by O'Leary that Ryanair may launch low cost long–haul services in the future. He called it a "logical extension" of the business model, although it would not happen for at least five years, until Ryanair reached a "critical mass" in Europe of carrying around 100m passengers a year (compared with the 35m passengers it expects to carry in 2005).

| Fleet | Order | Options | |

| 737-200 | 9 | ||

| 737-800 | 83 | 156 | 201 |

| Total | 92 | 156 | 201 |

| Revenue or | ||

| unit cost | ||

| Total € | (€ per pax) | |

| Scheduled revenues | 1,128,116,000 | 40.9 |

| Ancillary revenues | 208,470,000 | 7.6 |

| Total operating revenues | 1,336,586,000 | 48.4 |

| Staff costs | 140,997,000 | 5.1 |

| Depreciation & amortisation | 98,703,000 | 3.6 |

| Fuel and oil | 265,276,000 | 9.6 |

| Maintenance, materials and repairs | 37,934,000 | 1.4 |

| Marketing & distribution costs | 19,622,000 | 0.7 |

| Aircraft rentals | 33,741,000 | 1.2 |

| Route charges | 135,672,000 | 4.9 |

| Airport & handling charges | 178,384,000 | 6.5 |

| Other costs | 97,038,000 | 3.5 |

| Total operating expenses | 1,007,097,000 | 36.5 |