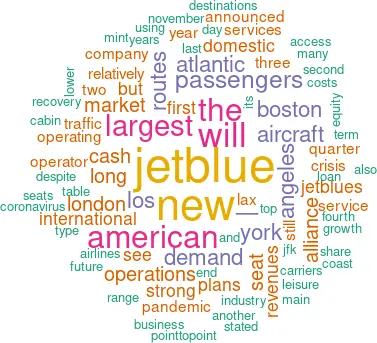

JetBlue: Creating opportunities

from the Covid crisis

December 2020

The US airline industry may have consolidated — the top three legacy network carriers of Delta, United and American, along with archetypal LCC Southwest, controlled 80% of industry revenues in 2019 — but there is still room for healthy innovation.

And over the past twenty years JetBlue has provided much of that innovation to have successfully grown to become the 6th largest player in the market just behind Alaska Airlines with 4.1% of industry revenues in 2019 (and 4.6% of passengers).

It entered 2020 as little prepared as anyone else for the crisis of the Covid pandemic. But it had been consistently profitable over the preceding decade, despite an average growth in revenues of nearly 10% a year, and had a relatively healthy balance sheet. Cash and cash equivalents at the end of Dec 2019 stood at $1.3bn (16% of annual revenues), long term debt (including leases) at $2.7bn with shareholders’ equity of $4.8bn (see table).

JetBlue was one of the first to act decisively in February in reaction to the approaching crisis — and was the first to abandon “change fees” in an attempt to bolster flagging demand (subsequently followed by the major network carriers and made “permanent”). As the operating environment worsened it worked hard to preserve cash, reduce fixed and variable costs: consolidating operations in New York, Massachusetts and Los Angeles; parking less efficient aircraft; implemented salary cuts of 20%-50% across the board. It took advantage of the government’s payroll support scheme to the tune of $1bn, drew down $550m from a revolving credit facility, $1bn from a term loan in March (fully repaid in the third quarter) and another $750m in June. In April it raised $150m from its co-brand credit card partner for the pre-purchase of loyalty points. It completed public placements of ETCs in the amount of another $1bn secured on 49 A321 aircraft in August and completed another $445m of sale and leaseback transactions. In the fourth quarter it started drawing on the $1.14bn loan facility from the Government provided under the CARES Act programme (and in November reached agreement with the Treasury to increase the loan capacity to $1.95bn).

In the first nine months of the year it registered total losses (on a GAAP basis) of $1.26bn at the operating level, and $981m after tax. But in doing so it had reduced its operating cash burn from over $18m a day in March to $7.8m/day in the second quarter and $6m/day by September. Management estimated that in the fourth quarter daily cash outflow would approach $4m. At the end of September JetBlue had $3bn in cash (37% of 2019 revenues), positive net current assets, and still had positive shareholders’ equity of $3.7bn. And then in December it bolstered its balance sheet further successfully raising $500m in new equity.

JetBlue does not seem to be deviating from its long term plans. At the end of the year it had 267 aircraft in its fleet (see table), on the last day of the year having taken delivery of its first A220, with outstanding orders for a further 69 of the type and 74 A321neos. In October the company renegotiated with Airbus the timing of the future deliveries of the A321 aircraft, effectively postponing 15 of the type into 2027 (see graph), but did not change the timing or the volume of the A220s. The company will be using the using these to replace its 60-strong fleet of ERJs, and pre-Covid had seen the type as an “economic game-changer” (see Aviation Strategy Jul/Aug 2018), providing a range of 3,300nm, 40% lower fuel burn and nearly 30% improvement in direct operating costs per seat and significantly lower maintenance costs.

During 2020, and despite the damage to operations caused by the collapse of traffic demand, JetBlue opened more than 60 new routes — more than it had done in the whole of the preceding five years.

CEO Robin Hayes explained that in normal (pre-Covid) times substantially all of the airline’s growth had come from adding capacity to existing routes, with only a handful of aircraft available to take on the “risk” of experimenting with new routes. But in the pandemic, he said, “everything is risky... Suddenly, we have planes on the ground and business travel demand that’s depressed for a while. It’s a fabulous time to experiment with routes.”

And he sees that the recovery in demand, when it comes, will lead fully into JetBlue’s strengths: short haul, domestic, point-to-point, and leisure oriented. In the pre-crisis market, over 80% of its traffic was leisure- or VFR-based, and 85-90% point-to-point.

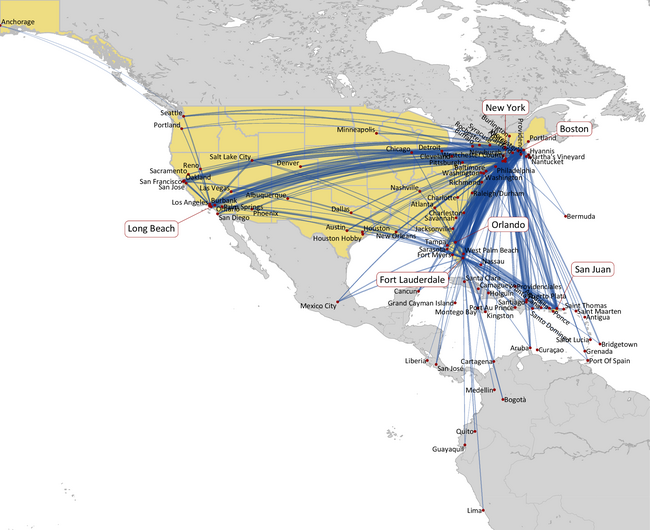

Equally important for its recovery plans is the position it has been able to build in its main “Focus cities". These have seemingly been chosen either as major metropolises that can be the source of strong originating demand, or those where there is equally strong demand as a leisure destination.

Based in New York (where it dubs itself New York’s Official Home Town Airline) it is the largest carrier at Kennedy airport, but has taken the opportunity of the crisis to expand services from Newark and La Guardia. Overall in 2019 it was the third largest domestic operator out of New York’s three main airports with a near 13% share of passengers (see table).

Its second most important city is that of Boston where it had a 29% share of passengers, well ahead of the second largest carrier Delta. It was also the largest operator at Fort Lauderdale and San Juan (there is no coincidence that New York has the largest community of State-side Puerto Ricans), and the fourth largest at Orlando.

Its other focus is Los Angeles. Here it had emphasised using Long Beach rather than Los Angeles International (LAX) and had built operations to dominate the small airport (3.5m passengers in 2019 vs 88m at LAX), carrying twice as many passengers as the next largest operator, Southwest. But taking all the Los Angeles airports into account JetBlue had gained a “natural” 4% share of the market. This traffic will now be consolidated at LAX following JetBlue’s alliance with American.

American alliance

In July, JetBlue and American Airlines announced the signing of a “strategic partnership”. The alliance between the two encompasses a slew of codeshare agreements and loyalty benefits and is focused on the US northeast coast and particularly JetBlue’s strengths at New York and Boston — JetBlue (in more normal times) carried twice as many passengers as American at JFK and 50% more than American at Boston. American saw the region as a gap in its nationwide coverage, in the same way the West Coast had been seen until a similar deal struck width Alaska at the beginning of 2020. The two carriers describe the alliance as providing seamless connections between their two networks, and the usual marketing hype of “giving customers new options with improved schedules, competitive fares and nonstop access to more domestic and international destinations”. The deal was tacitly approved by the DoT in November.

American in particular had allowed its international offering out of New York to stultify — the number of international destinations served had fallen by 40% since 2010 — but as part of the agreement has stated that it will immediately start new services to Tel Aviv, Athens and Rio and “once the coronavirus pandemic has ended... [the alliance will] facilitate American adding new long-haul markets in Europe, Africa, India and South America”.

JetBlue, however, has clearly stated that it will join neither the oneworld alliance nor the immunised joint venture that American has with British Airways, Iberia and Aer Lingus on the Atlantic. But it says it views the partnership “as the next step in our plan to accelerate our coronavirus recovery... and fuel JetBlue’s growth into the future”.

As a sign of future direction for JetBlue, in October it announced that it would close its base at Long Beach and concentrate all Los Angeles operations at LAX (where American is the leading player). It also in December announced its first routes into American’s hub in Miami (from Los Angeles, JFK, Newark and Boston).

Over the last decade JetBlue had been remarkably successful in encroaching on the longer range strong O&D domestic routes, particularly damaging the incumbents with its high quality low premium fare “Mint” service. The chart shows how by 2019 JetBlue had become the largest operator out of Boston to both Los Angeles and San Francisco and had made significant inroads into United’s lead out of New York to the west coast conurbations. They also exemplify American’s relative weakness.

Atlantic ambitions

In a presentation at the company’s Investor day back in 2016 the company had highlighted that it was present in 39 out of the top 50 domestic and international destinations from Boston with London, Paris and Dublin marked as “not currently served”. Given that London and New York are by far the largest gateways on the Atlantic it would be surprising not to try services to London.

Speaking at London’s Aviation Club two years ago, Robin Hayes announced plans to start operations to London in 2021, describing it as “the biggest metropolitan area we don’t serve” from its main hubs. Despite the coronavirus pandemic these plans seem still to be in place.

Three of the six A321neos still planned for delivery in 2021 and all three of those planned for 2022 are the long range variants. In November JetBlue was able to secure 14 slots a week at London Gatwick starting in the Winter 2021/22 season and a further 28 slots at London Stansted, but failed (unsurprisingly) to gain access to Heathrow.

JetBlue is most likely to fit out the aircraft with a form of its Mint premium service. The current Mint service JetBlue operates on transcon services is operated on 159-seat A321s: 12 full lie-flat bed seats (7ft6in bed length) and 4 closed “suites” in the front cabin, 41 standard seats in “Even More Space” cabin (37in-41in seat pitch) and 102 standard seats in the “Core” cabin (33in seat pitch); complimentary food service; seat back IFE with TV and films; AC power at each seat; relatively high speed wi-fi internet access. The company stated that it plans to reimagine the product offering for the European market.

JetBlue’s entry onto the Atlantic will be disruptive, but will it be successful? The Atlantic has been a graveyard for many wannabees from the all-business class operations of MaxJet and Silverjet at the top of the last cycle to recent casualties such as Norwegian in its attempt to pioneer long haul low cost.

However, JetBlue is embarking on the venture focused on its strong bases at JFK and Boston; its model is based on point-to-point O&D demand (only 10% of its passengers connect, while New York-London is the strongest O&D market on the Atlantic). Unlike Norwegian, it is attacking core routes with relatively small aircraft, an efficient cost base, and an excellent brand image.

The Atlantic market will have changed when traffic eventually recovers. Business travel volumes are likely to be smaller, and passengers will be more selective and much more price-sensitive. The incumbents will probably be forced to raise Economy fares to compensate for relatively lower Business revenue. All this will suit JetBlue.

| In service | Parked | Total | Avg Age | On order | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A220 | 1 | 1 | 0.0 | 69 | |

| A320 | 108 | 22 | 130 | 15.3 | |

| A321 | 60 | 3 | 63 | 4.5 | |

| A321neo | 13 | 13 | 0.8 | 74 | |

| ERJ-190 | 40 | 20 | 60 | 12.2 | |

| Total | 221 | 46 | 267 | 11.3 | 144 |

| Market | Passengers (m) | Share | Rank | Largest competitor | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New York† | 8.96 | 12.8% | 3 | United | 19.1% |

| Boston | 6.01 | 29.0% | 1 | Delta | 14.6% |

| Fort Lauderdale | 4.26 | 23.6% | 1 | Spirit | 23.1% |

| Orlando | 2.90 | 11.7% | 4 | Southwest | 21.6% |

| Los Angeles† | 1.94 | 4.3% | 6 | American | 15.8% |

| San Juan | 1.32 | 32.7% | 1 | American | 14.6% |

Notes: † includes all airports

| $m | September 2020 | December 2019 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flight equipment | 7,745 | 7,997 | |||

| Operating lease assets | 833 | 912 | |||

| Other P&E | 630 | 617 | |||

| Other assets | 770 | 606 | |||

| Cash etc | 3,019 | 1,328 | |||

| Other current assets | 436 | 458 | |||

| Current debt and leases | (513) | (472) | |||

| Air traffic liability | (1,253) | (1,119) | |||

| Other current liabilities | (1,042) | (1,072) | |||

| Net Current Assets | 647 | (877) | |||

| TOTAL ASSETS | 10,625 | 9,255 | |||

| Long term debt | (4,439) | (1,990) | |||

| Operating leases | (782) | (690) | |||

| Deferred taxes and other | (1,687) | (1,776) | |||

| LONG TERM LIABILITIES | (6,908) | (4,456) | |||

| SHAREHOLDERS EQUITY | 3,717 | 4,799 | |||

Source: Company reports