Copa: The Pandemic

in Panama

December 2020

Copa Airlines has been the most successful Latin American airline, as measured by profitability, growth, operational efficiency, brand perception, etc. It is also arguable that it has been the most successful pure hub-and-spoke, international-only airline in the world, though much smaller than Emirates, Qatar or SIA.

First of all, some highlights of Copa’s performance before Covid 19 shut the airline down in 2020.

-

Copa has been consistently profitable, with an average annual 10.2% net profit margin during the period 2011-19 (the only loss recorded was in 2015 when it incurred a $432m currency translation charge on funds held in Venezuela as a consequence of the extreme devaluation of the Bolívar).

-

Passenger volumes have grown at an annual average of 7.2% during 2011-19 reaching 15.4m in 2019, a year that was negatively impacted by the grounding of its 737 MAX fleet.

-

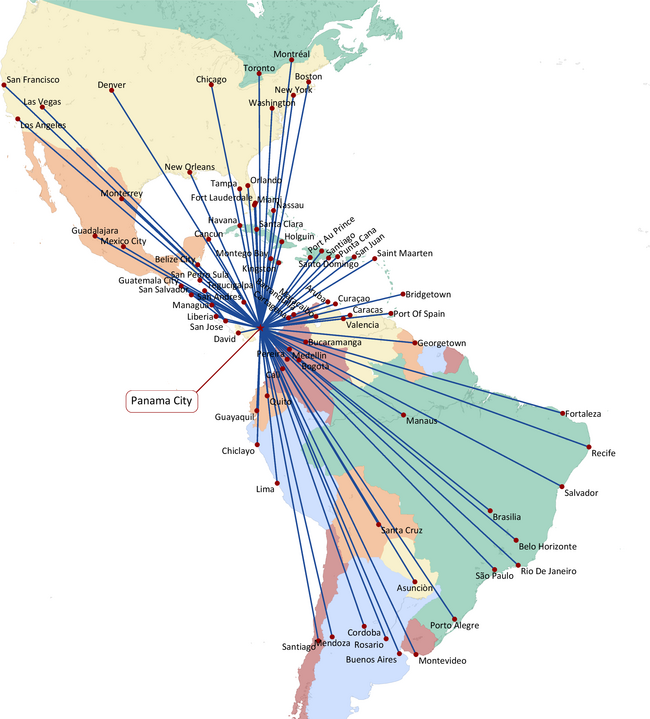

Operating out of its Tocumen hub to 80 destinations, with a narrowbody fleet averaging 104 units, Copa achieved 11.3 hours average daily utilisation and 3.7 departures per day per aircraft (average stage length of 1,288nm), while maintaining 99.8% schedule reliability performance and a 91.4% ontime performance in 2019.

-

Its operating cost per ASM was 9.4¢/ASM, roughly the same as Southwest, adjusted for stage length, and below that of JetBlue.

-

Its passenger unit revenue at 10.4¢/ASM was about 10% above those of Southwest and JetBlue, again adjusted for stage length, and 40% above its main Latin American rivals, LATAM and Avianca.

-

It markets itself as a full-service carrier and regularly picks up SkyTrax and other trophies for product and ontime performance.

-

Without any form of state funding Copa has maintained a strong balance sheet with the type of liquidity needed for reliance in the Covid crisis — at the end of 2019 a net debt to equity ratio of 0.8/1 and $850m in cash, nearly 32% of annual revenues.

-

The management team is long-established and highly regarded, led by CEO Pedro Heilbron. The Heilbron family and other prominent Panamanian families own 28% of the airline’s stock through an investment vehicle called CAISA which owns all the voting shares, and hence this group controls all major investment and ownership strategies; the remaining 72% of the share capital is listed on the NYSE.

That was 2019 and before. In March 2020 the Panamanian government closed down air travel to/from the country, reopening partially in mid-August, then in October removing restrictions on the entry of non-Panamanian citizens at Tocumen. In effect, Copa was closed down completely for 135 days, but by November had managed to resume service to 38 destinations, with traffic running at 20% of 2019 levels.

Net losses for the second and third quarters of 2020 have been reported as $504m. No official forecast is yet available for the full year, but the result will be dire.

However, its balance sheet afforded Copa the necessary protection, and it has not sought nor received state aid from the Panamanian government. In April it shored up its liquidity through a $350m convertible debt offering, with an interest rate of at 4.5% pa for five years; this debt was priced at about half that achieved by American Airlines for its bond issue at the same time.

As at September 2020 Copa’s net debt to equity ratio had risen to a still conservative 1.04/1 and cash has risen to $870m. In total Copa’s management estimates total available liquidity, including credit facilities, to be $1.3bn, more than comfortable with cashburn during the third quarter running at $36m a month, down from $76m in the first months of the pandemic.

The aim is to reduce cashburn further to $25m a month by the end of the year, but that clearly depends on how demand recovers. In November Copa’s RPMs were down 75% on the same month in 2019, and the load factor was down 7.3 points to 78.3%.

Pre-Covid about one third of Copa’s passengers were Panama O&D travellers and two thirds connecting passengers. Panama is a small but dynamic country whose GDP has hugely outperformed the rest of the Latin American — see graph — its economy is largely based on the Panama Canal. Containership and tanker transits through the canal have held up well during the Covid crisis, though cruiseship visits have more or less disappeared. Eco-tourism has potential. In September the government announced a five-year tourism plan with planned investment of over $300m, partly financed by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

However, for Copa the core business is connecting thin O&D markets through its Hub of the Americas strategy (there is one minor domestic route operated by Copa from Panama City to David). In 2019 Copa estimated that 81% of the O&D markets had less than 20 passengers per day each way. Note the contrast between Copa’s network that links multiple secondary points between South America, North America and the Caribbean and JetBlue’s network map, where traffic flows to/from the Caribbean and South America are dominated by the New York market.

Copa’s contention is that most Latin American markets cannot sustain point-to-point service in normal times let alone in a post-Covid market. Copa is best positioned to capture returning traffic, and by funnelling the various flows over its hub it will be able to smooth out variations in traffic recovery on different O&D markets. This will be a test of the resilience of its operating model.

Pre-Covid Copa had built up to a six-wave pattern at Tocumen. Even with a fairly robust traffic recovery in the second half of 2021 Copa will presumably have to redesign that wave pattern, perhaps reverting to its pre-2018 four-wave operation. On its dense routes — like Bogotá, Havana, Lima and Miami, which had six-plus daily flights in 2019 — Copa can operate efficiently at lower frequencies, but the lower density, single daily frequency routes may cause logistical problems: the prospective traffic volumes may not justify resuming operations but not restarting these sectors impacts connecting routes and damages the overall economics of the hub system. Lower frequencies also tend to lengthen connecting times at the hub which could undermine competitivity on some routes. Rebuilding a connecting network is always going to be more complicated than resuming a point-to-point operation.

More generally, Copa remains exposed to economic and political conditions in its main markets; after the US its most important country markets are Columbia, Brazil, Mexico, Ecuador and Argentina. In its October Economic Outlook the IMF observed that “the [Latin American] region contains only 8% of the global population, but it represents roughly 20% of Covid-19 infections and 30% of deaths from the virus. On the economic side, the region’s economy is projected to shrink by 8% in 2020, which is nearly double the 4.4% contraction expected worldwide. The economic outlook for 2021 shows the region will be playing catch up with the growth of 3.6% expected compared to 5.2% for the rest of the world”.

Fleet rationalised

Copa entered 2020 expecting to grow its fleet from 104 units to 120 in 2022, but it also had a flexible fleet plan whereby the end-2024 fleet could have totalled a maximum of 150 units or a minimum of 95, flexibility coming from retirement options, lease extensions and “slide rights” on MAX deliveries. In the event. Covid caused a radical revision of that plan — at the end of November the fleet, active and parked, consisted of 70 aircraft, 63 737-800s and seven 737 MAX9s. Management’s best guess is that the end-2021 fleet will be about 85.

To put a positive spin on the situation, the Covid crisis has accelerated Copa’s rationalisation of the fleet. The sale of the entire Emb 190 fleet has been completed, albeit at a significantly lower price, $79m in total, than was expected last year, and the aircraft will be delivered to the purchaser over the period to June 2021. The 14-unit 737-700 fleet has also been put up for sale and will not be operated by Copa again.

Copa has converted some of its leases on its 737-800s to power-by-the-hour agreements. Such agreements are usually made by airlines in financial distress but in Copa’s case the aircraft were coming to the end of their lease term and the lessor appears to have been more than willing to accept some income from power-by-the hour rentals than having to park unplaceable aircraft.

Following the recertification of the MAX, Copa will be one of the first airlines to restart operations, probably in early January. The MAXes parked in Panama are currently going through maintenance procedures to restore them to operational status while seven units, parked by Boeing at Seattle, are due for delivery over the next year.

The MAX grounding affected Copa badly in 2019 but not having to make progress payments in 2020 year has been a benefit. Negotiations are nearing a conclusion with Boeing on the compensation to be paid, whether in cash payments (no payments have yet been made by Boeing) and/or in delivery price reductions. Copa placed its 61-unit firm order in 2013 and, as one of the most important airline clients for the MAX, would have received a major discount, probably making the unit price close to the $54m believed to have been paid by Southwest, which is about half the list price. How much more Copa is aiming to cut the price to reflect grounding compensation is inevitably highly confidential

Copa’s rationalised fleet will consist of 737-800s with 154-160 seats (plans to densify the full NG fleet to 166 have been put on hold) and MAX 9s configured to 166 or 174 seats. Compared to the mixed Embraer/ 737-700/737-800 fleet, total unit costs per seat will be reduced by 6%, according to Copa.

Costs cut

Unit revenues will be under pressure for some time. Pre-Covid Copa had a strong business segment, over half the total volume, which allowed it to achieve RASM of 10.4¢ in 2019. The average one-way fare was $169. The traffic profile in 2020 changed to an equal division in passenger numbers between VFR, Leisure and Business, and this is likely to continue through 2021,according to the airline’s management.

Pre-Covid Copa had launched its “sub-6 Project”, a series of initiatives designed to bring its CASM ex-fuel down to under US¢6. It has intensified its efforts and slightly modified the target to include maintaining the 2019 ex-fuel CASM of US¢6.6 while operating at 70-80% of the 2019 level. It is seizing the opportunity presented by the crisis to attack fixed costs, aiming to take out 40% by renegotiating all supplier contracts, airport agreements and lease terms. There have also been extensive lay-offs of staff at the airline — Copa managed to cut its employee costs by 61% in the third quarter of 2020, when there was almost no flying, compared to the same period in 2019.

Construction of Terminal 2 at Tocumen airport is now complete and will fully open in the first quarter of 2021. This is the third phase of a long-term investment made by AITSA, the 100% government owned operating company, which will include a new runway and other infrastructure improvements. Copa, which in normal times accounted for over 80% of the throughput at Tocumen airport and which had been experiencing congestion problems, will consolidate all its operations in Terminal 2.

In the short term there could be a conflict of interest between the airline and the airport. Copa needs to at least freeze its airport costs while the airport management is under pressure from its bondholders, who have $1.45bn of Tocumen debt, to ensure compliance with its Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR) covenants, which would imply an increase in rates. In November AITSA obtained an additional $100m in government-guaranteed credit facilities, which should ease the liquidity concerns during 2021.

Chapter 11 carriers and the new competitive scene

Copa’s share price, quoted on the NYSE, has fallen by just 28% since March 2020 and the company is still has a stockmarket valuation of US$3.3bn. By contrast, shareholders in its three main listed rivals in Latin America — Aeroméxico, Avianca and LATAM — face being wiped out, their shares having been suspended when they entered into Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

The policy response to Covid in Latin America has been very different to North America or Europe; governments generally have refused to support distressed airlines. According to IATA the EBIT margin for Latin American airlines was -94% in the third quarter of 2020 compared to -91% for North America while state aid as a percentage of 2019 revenues was less than 1% for Latin America and more than 25% for North America.

The Chapter 11 bankruptcies of its rivals apparently present opportunities for Copa. But Pedro Heilbron’s comments at the results presentations have been low-key, stating that Copa was very happy to have avoided Chapter 11 as the outcome of the process was always unpredictable, but there was the possibility that going through Chapter 11 world enable its rivals to close the cost gap on Copa. In summary, Copa is “careful not to assume the weakness of others”.

Painful in the short term, in the longer term Chapter 11 bankruptcy may be a more effective response to the Covid crisis than government bail-outs, which perpetuate fundamental weaknesses and load the carrier with debt and political obligations. It depends on whether companies can take advantage of Chapter 11 protection to effect fundamental cost cutting, management change, network/fleet streamlining, etc.

Aeroméxico, Avianca and LATAM have all managed to attract investors, while operating under Chapter 11, and those investors will be expecting radical restructuring and financial returns.

Aeroméxico entered 2020 in a weak state, losing market share to dynamic LCCs like Volaris and VivaAerobus, and just about breaking even at EBIT level. After two months of Covid the airline had burnt through almost all its cash reserves and its net asset value was negative to the tune of -$1bn. Delta, which owned 49% of the carrier, was unable to further support its Mexican partner. Aeroméxico declared Chapter 11 in June, with CEO Andrés Conesa making some optimistic noises about using the Chapter 11 process to re-invent the airline, cutting its cost base, terminating leases and switching to Power by the Hour contracts, and rationalising its fleet from 122 aircraft at mid-year to around 80 units.

Aeroméxico attracted a Debtor-in-Possession (DIP) investor — the New York-based private equity giant, Apollo Global Management, which has agreed a loan of $1bn to be delivered in tranches of $100m providing various turn-around targets are met. DIP financing for companies under Chapter 11 protection has to be approved by the US bankruptcy courts as it confers on the investor first claim on the company’s assets if it ends up in Chapter 7.

Columbia’s Avianca was also in a poor financial state pre-Covid, reporting a net loss including exceptional items of US$894m on revenues of $4.6bn for 2019. In May Avianca filed for Chapter 11 protection.

In October Avianca received approval for DIP financing totalling just over US$2.0 bn. United and other investors committed $722m and, as a condition of their loans, will have “super-majority” control of the airline. $1.3bn was raised in DIP loans from institutional investors in an offering coordinated by JP Morgan, the notes bearing interest rates of LIBOR plus 10.5-12 points. According to Anko van der Werff, CEO of Avianca, “… with this DIP financing, Avianca has ample liquidity to support our operations …”.

Before the crisis United held a majority share, but not majority voting rights, in Avianca, and had been pursuing a tripartite antitrust-immunised alliance with Avianca and Copa. That agreement was not filed with the US DoT before Avianca’s bankruptcy and is now in limbo.

The relationship between Copa and Avianca has been complicated by the success of Wingo, a Bogotá-based ULCC which Copa converted out of a formerly loss-making full service subsidiary in 2016. Pre-Covid, Wingo was expanding rapidly and appears to have been resilient throughout the Covid crisis, with its fleet expanding from five to seven 737-800s leased from its parent.

LATAM, the continent’s preeminent carrier, was apparently in a strong position pre-Covid. Its net result in 2019 was $887m, and in January 2020 Delta finalised an agreement to buy 20% of the airline’s shares for $1.9bn and to invest a further $350m in expanding the joint venture.

However, having recorded a $2bn net loss in the first quarter of FY 2020 and unable to access state aid from either Chile or Brazil, LATAM filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in May. While Delta has continued the legal process to obtain an antitrust-immunised codeshare for itself and LATAM, finance for the Brazilian/Chilean carrier has come from other sources. $900m in DIP finance was raised from the Cueto family, which controls 21% the airline, and Qatar Airways which has 10%.

Oakland Capital Management, a Los Angeles-based fund that claims to be the world’s biggest investor in distressed companies was the key investor, committing to $1.3bn. The effective interest rate on Oaktree’s DIP financing might be regarded as distressing — LIBOR plus 11 points plus fees, adding up to an estimated 14.2%pa. This is a major incentive for LATAM to achieve a rapid turn-around and recapitalise.

The post-Covid competitive scene will be intriguing: no significant state-controlled flag carriers; the main full-service network carriers forced to go through Chapter 11 restructurings that might produce powerful new airlines or might force them out of business; the dynamic LCCs in Mexico and Brazil; and Copa Airlines. Its core strategy is convincing: focus intently on rebuilding the Panama hub and use the crisis to strip out costs.

| September 2020 | December 2019 | |

|---|---|---|

| Fleet and other fixed assets | 2.43 | 2.82 |

| Held for Sale | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| Investments | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Intangibles | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Receivables | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| Cash etc | 0.87 | 0.85 |

| Others | 0.18 | 0.20 |

| TOTAL ASSETS | 3.89 | 4.36 |

| Long term debt | 1.61 | 1.38 |

| Short term liabilities | 0.80 | 1.04 |

| TOTAL LIABILITIES | 2.41 | 2.42 |

| SHAREHOLDERS' EQUITY | 1.48 | 1.94 |

| In service | Parked | Total | Average age | On Order | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 737-700† | 14 | 14 | 18.4 | ||

| 737-800 | 51 | 12 | 63 | 8.0 | |

| 737MAX8 | -- | 33 | |||

| 737MAX9 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 1.5 | 6 |

| 737MAX10 | -- | 15 | |||

| Total | 54 | 30 | 84 | 9.2 | 54 |

PANAMA AND LATIN AMERICA TOTAL

HUB FREQUENCY BY HOUR (PRE-COVID)