Emirates: Relentless expansion, political defensiveness

Jul/Aug 2011

After unveiling its twenty–third consecutive year of profit, Emirates is mounting a fierce counter–attack to charges that it benefits from substantial direct and indirect help from the Dubai state. The airline appears to have identified a protectionist backlash from Western network carriers as the main threat to its apparently relentless expansion.

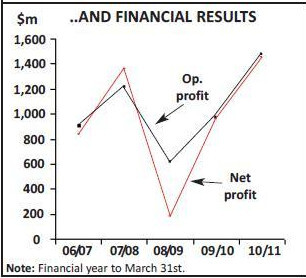

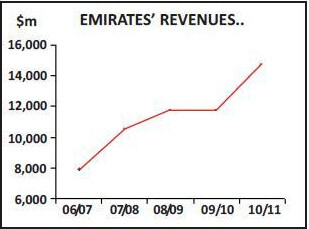

For an airline founded only in the 1980s, the rise and rise of Emirates is staggering. In the 2010/11 financial year (ending March 31st) the Emirates Group shrugged off rising fuel prices and last year’s volcanic ash disruption to record its twenty–third consecutive year of profit (having made a loss in just one year since launching), with revenues rising 26.4% year–on–year to US$15.6bn and operating profit up 44.1% to $1.6bn.

The Emirates Group includes Dnata, the largest airport service company in the Middle East with contracts at 75 airports around the world, and more than 50 other business units, but the vast majority of group revenue and profit comes from the airline operation, which saw a 25.2% rise in revenue to $14.8bn in 2010/11 and operating profit up 52.6% compared with 2009/10, to $1.5bn. Emirates SkyCargo, which operates eight freighter aircraft and the space on passenger aircraft, saw revenue rise 27.6% in 2010/11 to $2.4bn. But profit at the mainline would have been $272m higher if it had not been for a 41% increase in fuel prices to $4.6bn in 2010/11, which now accounts for 34% of the airline’s total operating costs.

Emirates is also having to cope with the effect of the so–called “Arab Spring” (which directly forced rival Gulf Air to cut 200 jobs).

Emirates says that this has impacted on traffic in the region, although it reacted swiftly to pull out of Libya and reduce capacity in Egypt and Tunisia as soon as unrest hit those countries. It’s interesting to note that while the UAE is very stable compared to the rest of the Middle East but political freedom is restricted, and there always must be a degree of concern, however small, about the tensions caused by the extent of conspicuous consumption in the region.

Importantly for Emirates, premium traffic recovered well in 2010/11, and overall passenger yield rose 8.5% in the last financial year when Emirates carried 31.4m passengers in total, a 14.5% increase on the year before. While capacity rose by 13% in the year, traffic rose faster — at 15.7% — and so load factor rose 1.9 percentage points to exactly 80%.

Massive orders

Emirates currently operates to more than 110 destinations in almost 70 countries but the long–term aim is to operate to “several hundred destinations”, according to chairman and chief executive Sheikh Ahmed bin Saeed al Maktoum, adding that “I’m sure this will make a lot of people unhappy but the market is there to grow. Airlines in Europe don’t want to see us there because we are giving them competition.”

The fleet has 153 aircraft (see table, page 10), of which 93 are Boeing models and 60 Airbus, but what makes Emirates unique is that has a huge order book totalling some 213 aircraft, with another 117 aircraft on option. On its own, Emirates accounts for more than 3% of the firm order book at Airbus and Boeing combined.

Those firm orders include 15 747–8Fs, six 777–200Fs, 47 777–300ERs (orders for 30 of which were placed last year) and 70 A350s, of which 50 are -900 models and 20 are — 1000 variants. The A350s were ordered back in 2007 but today the airline says that it now doesn’t really need aircraft with less than 300 seats, and so the 290–seat -900s may change to larger capacity -1000s, which will have at least 320 seats.

However, a complicating factor is that while the -900s would be delivered from 2015 onwards, the stretched -1000s do not yet have a delivery date to Emirates as their design has still not been finalised, with various airlines around the world lobbying Boeing for different features to be included in the -1000 variant. If Emirates does decide to switch to the -1000 model it would then use the 30 extra 777–300ERs ordered last year to fill in capacity while it waits for the–1000s.

On top of all those are orders for 75 A380s, making Emirates the largest single customer for the model. 32 of these orders were placed in 2010 and the Dubai–based carrier wants a total fleet of around 120 A380s, a statistic that some analysts and not a few rival aviation executives find difficult to rationalise in terms of finding enough routes where they could be utilised profitably.

Eight aircraft were delivered to Emirates in the 2010/11 financial year ending March 31st (including seven A380s), and this year six A380s and 13 777s are being delivered, but from 2012 Emirates will receive new aircraft at the rate of two per month for at least the following six years.

However, earlier this year Andrew Lobbenberg, equity analyst at the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) calculated that Emirates will easily be able to find enough routes for the A380s it has on order, and not only that but that the airline is likely to place a substantial amount of new orders in the latter part of this decade and the next as it continues its global expansion. Already there are signals coming from Emirates that it may announce major new aircraft orders at the Dubai air show this November.

The RBS analyst report commented that in the period to 2015 the A380s will spread throughout Emirates’ routes to Europe, North America, Australian, China and Japan, and that in the last part of the decade the emphasis in new A380 capacity will turn to North America and southern Asian destinations.

RBS also forecasts that the Emirates fleet will reach 250 by the end of the decade, which it points out is substantially smaller than the Lufthansa group, for example. Indeed some of the aircraft on order will replace almost 70 older widebodies (A330- 200s, A340–300/500s and 777s) that Emirates began to phase out from February this year. As can be seen in the chart, below, as the fleet has grown through the last decade the average age has crept up and is more than six years, although this will drop as new aircraft are delivered and older widebodies are disposed of.Still, the pace of route expansion will need to rise substantially; just six new destinations were added in the last financial year, to Amsterdam, Prague, Al Medinah al Munawarah, Madrid, Dakar and Basra – although capacity was added to many existing routes, with A380s introduced on services to Manchester, Beijing and Hong Kong, as well as being re–introduced onto the New York route.

In April Shanghai became the thirteenth Emirates destination to be served by the A380, joining the other Chinese routes of Beijing and Hong Kong, but the likely deployment of the model over the next decade is pretty clear from the current expansion priorities for the carrier, which are Asia and the Americas.

As can been seen in the table, right, the most important market for Emirates in terms of revenue is what it terms “East Asia and Australasia”, and although the Americas is currently the smallest market for the airline it is also the fasting growing region, with revenue up 31% in the last financial year. One of Emirates’ strengths is that its revenue base is geographically diverse, with no one region accounting for more than 30% of revenue, and the airline is keen to increase the revenue contribution from the Americas as it seeks to diversify its revenue base.

Emirates currently operates to four US destinations (New York, Houston, Los Angeles and San Francisco), with another point due to be announced soon. Capacity is increasing to most of these – A380s have returned to the Dubai–Newark route and are likely to be added to the San Francisco service as well at some point. Emirates also operates a Dubai–Toronto route with A380s but further expansion into Canada is restricted by the current bilateral, in which UAE airlines are allowed only seven flights a week between the countries. Currently Emirates and Etihad have three flights each, but both have been lobbying hard to increase this, quoting the very high load factors on the routes.

On the other side Air Canada has been pressurising the Canadian authorities to resist a change in the bilateral, claiming there is not enough traffic between the two countries. At one point the row between the two countries became so heated that the UAE refused to renew the lease on a Canadian military base in Dubai, though the argument seems to have calmed down, and Emirates is hopeful a liberal bilateral will be signed at some point in the not–too–distant future.

In South America, Emirates only serves Sao Paulo, although a daily non–stop Dubai–Rio de Janeiro route, going on to Buenos Aires, will start in January 2012 and routes to Santiago and Lima are the next on the list of target destinations. Emirates also wants to increase weekly flights to Australia from the current 70 services, although the current bilateral restricts the airline to a maximum of 85 flights.

Europe will see the addition of a twenty–seventh destination in August with the launch of daily non–stop flights between Dubai and Copenhagen (which will take total destinations in the Emirates’ network to 112), but the airline has run into problems in Germany, where the existing bilateral restricts UAE airlines to four airports in the country, much to the frustration of Emirates, which already operates almost 50 flights a week between Dubai and Frankfurt, Munich, Düsseldorf and Hamburg, but which also wants to launch routes to Berlin and Stuttgart. Germany doesn’t want to alter the existing bilateral, so all Emirates can do is add capacity to the four existing services (including using A380s on the route to Munich).

Emirates’ relentless addition of capacity can be seen in the chart, below, although it is interesting to note that the rise in ASKs has been accompanied by an increase in load factor (other than in 2008/09). That certainly backs up Emirates’ claims that the routes it serves are under–served and that there is plenty of scope to add capacity and routes into its network as the new aircraft come on stream.

In terms of code–shares, until now Emirates has linked with just a handful of airlines, although partnerships with JetBlue and Virgin America were signed late last year, and many more are likely to be signed over the next few years as new markets join the Emirates’ network.

Infrastucture constraints

Future expansion, however, depends on overcoming infrastructure constraints, with Tim Clark, president of the Emirates airline, saying that "physical constraints are the single largest inhibitor to our growth, including which airports can take the A380 and how quickly the Dubai hub can be built to match our expansion. If it hadn’t been for those inhibitors we would have placed much larger orders for expansion over the next 10 years”.

Indeed Emirates’ entire strategy is based on its geographical advantages, and specifically that two–thirds of the world’s population is within an eight–hour flight of Dubai. The value of the Dubai hub to Emirates is immense, and no less than 60% of all Emirates’ passengers transfer through the hub. Along with rivals such as Etihad Airways and Qatar Airways, it’s not an exaggeration to say that Emirates has been at the forefront of a restructuring of global traffic flows; for example, traffic that previously operated between Europe and Africa now tends to go via the Gulf region, thanks to the large onwards networks operated out of Dubai and other local hubs.

Following the opening of Terminal 3 in 2008 (which is used exclusively by Emirates), Dubai airport can handle more than 60 million passengers a year, operating 24 hours a day (much to the envy of some European airports). However, in 2010 international passengers to/from Dubai airport totalled 47.2 million – almost double the figure carried in 2005, and there is limited apron capacity, with Emirates saying it would have had placed even more A380 orders if it wasn’t for the fact that there is not enough space at Dubai airport to park them overnight. That problem will only go away once the airline transfers operations to Al Maktoum International airport, which will be open for passenger operations in 2012 and be fully operational by the end of the decade.

Incidentally, Emirates appears not to be affected by the rise of FlyDubai, the LCC launched in 2009 by Al Maktoum, the chairman of Emirates. FlyDubai operates out of Dubai with a fleet of 17 737–800s to more than 30 regional destinations, has 38 737 aircraft on order, and recently announced it was recruiting another 600 pilots over the next five years.

Finance

Assuming that Emirates finds enough new routes and markets for the massive amount of new capacity being added over the next five years, the other question mark on Emirates’ strategy is just how it’s going to pay for all those aircraft, with fleet investment of $38bn needed in the period to 2017. In fact Emirates’ financial position is strong; cash rose to $4.4bn at the end of March 2010, which Al Maktoum says “is a nice cushion to have” given the uncertainty on where fuel prices will go, and the airline has found little difficulty in raising debt as needed.

Currently only a handful of aircraft are owned outright; 70% of the fleet is under operating leases and almost all the rest are on finance leases, and this June Emirates financed the delivery of 10 new aircraft (five 777s and five A380s) being delivered over the next 12 months through three foreign entities — Doric Asset Finance of Germany, Natixis from France and San Franciscobased Jackson Square Aviation. The aircraft are worth $3bn at list prices, but of course Emirates has secured them at substantial discounts to those sticker prices.

To strengthen its balance sheet, this June the Emirates Group closed the issuance of $1bn worth of bonds, which were listed on the London stock exchange and which have a five–year term at a semiannual coupon of 5.1%. Emirates had originally looked to raise $0.5bn but the strength of demand was such that the group decided to double the amount raised, which will be used for “general corporate financing purposes”.

Emirates repaid a seven–year $0.5bn bond that matured in March this year, and as at the end of March 2011 the airline had long–term debt of USS6.5bn, which was 21.2% up on a year earlier.

Nevertheless, the impending large rises in capacity will probably hit Emirates’ profitability in the medium–term as the airline chases passengers in new markets, but while Emirates is likely to return to the bond market in the future, more cash is likely to be raised whenever Emirates carries out an IPO. The Group insists that an IPO is not on the cards either this year or in 2012, but it is likely that one is coming in order to secure a partial exit for the Dubai government. A quoted company would also make it easier for Emirates to carry out an acquisition or merger, but although Etihad and Virgin Atlantic have been rumoured to be of interest, Clark says that "getting sidetracked into a merger, acquisition or alliance would bring us to a complete stop as half the time our DNA does not jibe with other airlines."

But there’s another reason why an IPO may come sooner rather than later; an injection of new investors may ease some of the rising political pressure that Emirates Group is facing due to its closeness to the Dubai emirate.

Emirates and the state

Perhaps mindful of a future IPO, Emirates is at the forefront of the fight back against claims by European airlines that Gulf carriers have certain “unfair” advantages in the global aviation market. In January this year Ulrich Schulte–Strathaus, secretary general of the AEA, said that the expansion of the three main Gulf airlines made him "uneasy", and other airlines have weighed in with accusations that Emirates is effectively heavily subsidised by the Dubai emirate, whether in terms of export credits guarantees when buying new aircraft or the hefty support given to airport infrastructure.

Emirates appears to have taken a conscious decision that it can longer stand back as criticism grows, and earlier this year hit back with a claim that a “troubling trend is emerging”, and that Western airlines were co–ordinating activity to deliberately limit the growth of Gulf airlines.

Specifically, Emirates insists it does not benefit from subsidised fuel costs, nor indeed from subsidies of any kind, and points out that the airline has paid a total of $1.6bn in dividends to its owner, the state–owned Investment Corporation of Dubai, since 2002.The airline does use export credit–backed funding but it says that this is an acceptable practice worldwide, and that in the 14 year period ending in 2010, of the total $22bn raised to finance new aircraft “just” $5.2bn came from EU/US credit agencies. Emirates also says that it pays similar fuel rates as airlines pay elsewhere in the world, and that it does not get preferential treatment at Dubai airport.

Emirates does not pay any airport taxes at Dubai airport, which Emirates says is part of the “tax–free regime that prevails in the UAE and which existed before Emirates started flying in 1985”. In fact, the non–tax regime affects all aspects of Emirates’ cost structure – fuel, emissions, personal income, corporate profits, etc. – and this understandably infuriates Western network carriers which are over–burdened by taxes.

But there is little that they can do about it, apart from reverting to protectionist measures, which eventually will rebound on them and their home economies. The playing field in aviation just isn’t level.

In June a study released by UK consultancy Oxford Economics claimed that the Dubai aviation industry has not benefited from government support of any kind – although this report, called Explaining Dubai’s Aviation Model, was directly commissioned by Emirates itself. Unfortunately, as a result, the report’s unremittingly positive findings about Emirates, Dubai Airport, the local economy and global aviation read rather more like a propaganda exercise than an objective analysis.

Nevertheless, the report reveals some interesting facts – while the Emirates airline employs 30,000 people (see chart, left), the aviation sector directly supports 58,000 jobs in Dubai, rising to 125,000 if indirect jobs are included, contributing some $11.7bn a year to Dubai’s economy.

But whatever reports Emirates commissions, the criticisms of the friendly regime that the airline operates in will not go away, and is only likely to increase as the fleet and network reach of Emirates keeps on expanding.

| Type | In Service | On Order | Options | ||||

| A330-200 | 27 | 3 | |||||

| A340-300 | 8 | ||||||

| A340-500 | 10 | 10 | |||||

| A350-1000 | 20 | ||||||

| A350-900 | 50 | 50 | |||||

| A380-800 | 15 | 75 | 10 | ||||

| 747-400ERF | 3 | ||||||

| 747-400F | 3 | ||||||

| 747-8F | 15 | ||||||

| 777-200 | 3 | ||||||

| 777-200ER | 6 | 5 | |||||

| 777-200F | 2 | 6 | |||||

| 777-200LR | 10 | ||||||

| 777-300 | 12 | ||||||

| 777-300ER | 54 | 47 | 39 | ||||

| Total | 153 | 213 | 117 | ||||

| Revenue | |

| Middle East | 10.6% |

| Europe | 27.2% |

| Americas | 10.4% |

| E. Asia/Australasia | 29.2% |

| W. Asia/Indian sub-continent | 12.1% |

| Africa | 10.5% |

| Total | 100% |