Cathay Pacific: Western approach to the East

Jul/Aug 2011

As the hub carrier in Hong Kong, Cathay Pacific provides one of the major international gateways into China – the world’s economic powerhouse – which in the medium term is likely to provide the highest rate of air traffic growth of any region in the world. Cathay should be able to benefit strongly from this growth, assuming it can exploit its strategic link with Air China.

Hong Kong itself as a major financial and manufacturing centre provides a solid level of point to point demand, and the economy is again growing strongly: after a 2% contraction in 2009 the GDP grew by 7% in 2010 and recent IMF forecasts suggest annual GDP growth of 4- 5% a year for the next few years. China, however, saw GDP grow by 10% in 2010 (and it was hardly affected by the global slowdown) and the economy is forecast to increase at a similar rate of between 9% and 10% in the medium term.

Statistics from CAAC show that Chinese airlines' total air traffic growth in RPKs has averaged 15% a year in the past decade – with an average annual compound growth of 16% on domestic routes and 12% on international routes. Included within domestic routes those to Hong Kong and Macau (which exclude Cathay’s and Dragonair’s figures) have seen annual average growth of only 7%. However in 2010, total domestic traffic grew by 16%, Hong Kong and Macau traffic by 29% and international traffic increased by 33%. With its large population, increasing urbanisation and strong growth in per capita incomes the Chinese originating market is growing fast. It overtook Japan as the largest originating tourist market in 2003 and is expected to provide some 65m people travelling overseas in 2011. By 2020 the WTO estimates that this will grow to 100m people a year.

Cathay has one of the major gateways into China – but is seeing increasing competition from the developments of Air China at Beijing, China Eastern at Shanghai and China Southern in neighbouring Guangzhou. Also, the number of international gateways away from the major three mainland hubs is likely to grow as China increasingly opens; and as the PRC progressively permits cross–Straits flights to Taiwan there is a possibility of increased erosion of transfer demand between Hong Kong and the island.

Even so, the Hong Kong–Taipei route is still the busiest international route in the world with nearly 6m passengers in 2010 (and Cathay operates 108 flights a week to Taipei and 28 a week to Kaohsiung). (Meanwhile, of note, the route between Hong Kong and Shanghai is the world’s sixth densest route with over 3m passengers a year and five of the top ten international routes in Asia involve Hong Kong).

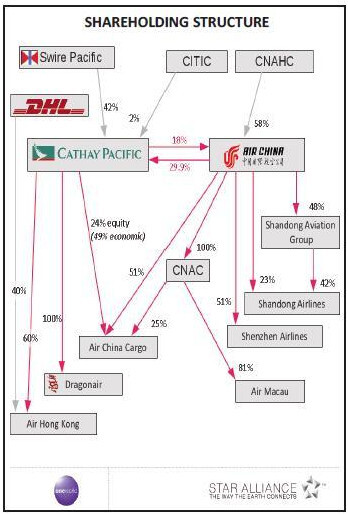

Relationships in China notoriously take time to develop. Cathay Pacific, its immediate parent Swire Pacific and ultimate parent John Swire & Sons have a distinct advantage in their commitment to the region over the past 160 years; and a strong positive benefit from being one of the British hongs not to have left Hong Kong on the handover to the PRC in 1997. Cathay has been positioning itself with the Chinese aviation operators for the past 20 years. In the early 1990s the group accepted an investment from mainland government fund CITIC and CNAC in return for relinquishing control of Dragonair which had achieved significant access to mainland Chinese routes. In 2004 on the IPO of the new Beijingbased Air China, Cathay acquired an initial 10% stake. Two years later and nearly ten years after the handover, in 2006, Cathay and Air China created a mutual strategic partnership in which among other things Cathay took back full control of Dragonair (at last providing the opportunity to develop a true network transfer operation at HKIA) increased its shareholding in Air China from 10% to 17.3% while Air China acquired a 17.5% stake in Cathay. In 2009 this was extended by a further realignment of shareholdings: Air China increased its stake to 29.9% and Swire Pacific its interest in Cathay back above 40%.

The fact that the two carriers are in different global branded alliances – Cathay a founding member of one world and Air China in Star – may be irrelevant given the growth potential in their local markets.

Last year the two carriers also received regulatory approval for a cargo joint venture which has been put into effect this year: based in Shanghai and using Air China’s existing cargo subsidiary Cathay will be selling a handful of 747–400BCFs and providing management expertise. Cathay has a 24% equity interest (funded by the sale of the freighters) and an additional 25% economic interest in the JV.

Cathay’s current strategy is stated as:

- to develop HKG as one of the world’s leading aviation hubs

- fully support the development of a third runway at HKIA

- no compromise in quality and brand, strong service proposition to the customer

- develop benefits from the strategic relationship with Air China

- prudent financial approach

It recognises that its cost base remains relatively high in comparison with near neighbour competitors and that its competitive advantage is in the quality of operation and service. It is concentrating increasingly on developing frequencies of lower capacity aircraft on long haul routes to maximise the premium potential and minimise the requirement to fill the back–of–the bus on ultra low fares; while recognising that the most valuable transfer traffic is the premium transfer traffic and that to build and maintain an efficient transfer hub at Hong Kong high value transfer traffic is required. The recent order for A350s (see below) is in part to provide a replacement for the ageing and operationally expensive 747s and A340s. Were the third runway at Hong Kong not to gain approval, perhaps this fleet strategy must needs change; and in time the group would reconsider the A380 or 747–8 for high density routes.

Recent performance

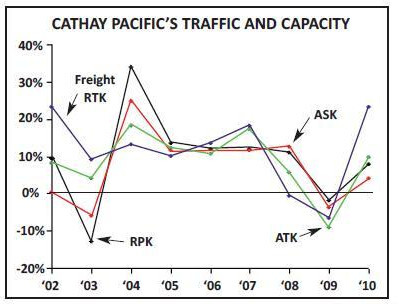

Cathay has benefited strongly from the region’s growth in the last ten years. Since 2001 total passenger traffic in RPK has grown by a compound annual average 9% — despite the gyrations of the impact of SARS in 2003 and the post–Lehman downturn in 2009. Freight traffic has grown faster with a compound annual growth of 11%; while total capacity in ATK has increased at an average 8% a year.

It has increased its route network substantially with 146 destinations served in 2010 up from 56 in 2001; and in doing so it has managed to improve staff efficiency (in terms of ATK per employee) by an average 4.5% a year. Between 2000 and 2007 it remained consistently profitable, averaging a 9.2% operating margin and 7.5% net margin.

In 2008 with the turn of the cycle, the group turned in its first major loss of over HKD8bn (US$1bn) – but almost all was due to the need to mark hedging contracts to markets (along with a provision for its share of similar losses at Air China). Despite the weak operating environment in 2009, the company still managed to return a profit – of HKD4.6bn – and this time saw a HK$2bn recognition of mark–to–market profits on fuel hedge contracts. The balance sheet had been badly impacted by the 2008 losses – with net debt to equity rising from 30% to 69% and the group decided to sell nearly half of its 27% holding in HAECO to parent company Swire Pacific.

In 2010 the group benefited strongly as passenger demand – both premium and economy — as well as freight demand bounced back from the recession. Total passenger capacity increased by a modest 4% as the group gradually restored services halted in the previous year – particularly from June onwards. Passenger demand grew at twice this rate and the total numbers of passengers increased to a record for the company of 26.8m up by 9%. The recovery in premium demand from the lows of 2009 along with reasonably strong economy demand led to a 20% bounce back in yields – almost back to the level of 2008 – and total passenger revenues jumped by nearly 30%. The recovery in the freight business was more dramatic with an 18% growth in freight traffic while capacity increased by 15% as the group progressively dusted off the sand from the freighters it had parked in the previous year. Freight yields recovered by 25% and total freight revenues increased by over 50%.

Total group revenues were up by a third on the prior year levels. Fuel prices however rose by 28% during the year and total fuel costs excluding hedging increased by 40% year on year: total fuel expenditure accounted for 36% of total costs. Further to improve the balance sheet the group sold its remaining 15% in HAECO and its shareholding in Hactl to parent company Swire Pacific, helping to generate exceptional gains of HK$2bn. In addition, the group recognised a gain of nearly HKD0.9bn on the deemed disposal of shares in Air China (as it did not participate in a rights issue) and nearly HK$2.5bn from the share of the results of Air China itself. Total operating profits reached HK$11bn and net profits an extraordinary HK$14bn or 15% of revenues. Even excluding the asset sale gains the net profit however would still have represented an exceptional 12% margin. As a result of all these effects the group restored its balance sheet to its more normal conservative 28% net debt to equity – and restored year–end cash balances to HK$24bn from HK$17bn at the end of 2009.

2011 first half trading

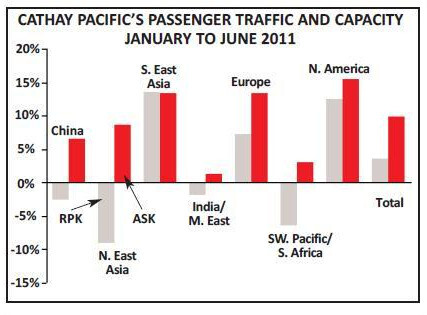

The restoration of capacity growth in the latter half of 2010 has continued into the current year with an increase in RPKs of 9% in the first six months. The company states that premium demand has remained consistently strong and that it is registering continued yield improvements in both premium and economy cabins.

However there appears to have been a weakness in demand in economy class, and total passenger demand in the first six months has only increased by 3.6% giving a five point decline in load factors to 79%.

Demand by region also appears mixed.

Unsurprisingly traffic to and from Japan has been hit by the aftermath of the earthquake and tsunami, and demand on North East Asian routes is down by some 9% cumulatively year on year; traffic on routes to SW Pacific and South Africa are also down by 6%. Disturbingly, traffic on Chinese mainland routes is also down by 2.5% year on year against a 7% increase in capacity – in contrast to figures from the mainland carriers suggesting growth. On the other hand traffic on routes within South East Asia is up by 14%, to North America up by over 12% and to Europe by 7%.

The concern may be that the persistently high oil price (and the necessary fuel surcharges) are having dampening effect on tourist demand. Freight traffic however does seem to be showing significant softness with monthly year on year declines since April and a total growth for the six months of only 0.5%. The company states that this weakness has been most pertinent in its main markets out of Hong Kong and mainland China giving concern for coincident economic activity in the region – although it is the weak season of the year. However, there has apparently been an interesting improvement in inbound demand, particularly for high value imports into China which is starting to produce a better traffic flow balance (always the headache of full freight cargo airlines). Meanwhile the Air China Cargo joint venture finally got under way in March and is showing modest performance with load factors around 60%.

Fleet and capex

Cathay has managed its fleet conservatively and consistently but is currently entering a period of fleet renewal. The fleet has an average age of 14 years – but the oldest of the passenger 747s are 22 years old, while the earliest 777s, A330s and A340s were built in the early 90s. It appears that the company will be replacing its fuel expensive four engine aircraft with twin engine equipment. Towards the end of 2010 the company announced its largest ever aircraft order for 30 A350XWB (+10 options) for delivery between 2016 and 2019 and six additional 777- 300ERs, supplemented by an order for another two A350s in December.

Earlier this year it announced an order for 15 new A330s and 10 777–300ERs. In addition it has orders for 10 747–8Fs and an additional 14 options. Originally slated for delivery in 2009 the first new generation 747 freighter is now expected in the second half of this year – and considering the fuel costs of the classic long range version no doubt eagerly awaited. The current order book stands with 86 aircraft due for delivery in the next eight years and additional options for 24 aircraft. In the 2010 annual report the company also suggested that it was in negotiation for another order for a further 14 aircraft. Meanwhile it still has one A330 and three A340s in storage – the latter likely to be returned to lessor.

The group is expected to use these orders in part for replacement and part for growth; but in doing so it aims to reduce the average size of aircraft in order to concentrate on premium traffic potential rather than physical seat capacity. This acquisition plan is likely to lead to a gross capital expenditure requirement of some HK$45bn over the next three years.

Also, the company is in the process of building a state–of–the–art cargo terminal at HKG. Put on hold in the depths of the financial crisis, originally designed to open this year, the group restarted the project in 2010 and now expects to be able to open it in 2013 presenting “an unwavering commitment to Hong Kong as an international air cargo hub”. This will be a common facility terminal managed by an arms–length subsidiary of Cathay and run on a 20 franchise form the airport authority, designed to cope with 2.6m tonnes of cargo annually: the total cost of construction is estimated at HK$5bn.

HKIA has recently published proposals for the development of the airport in Hong Kong over the next twenty years. It appears likely that HKG will run out of capacity by 2020 on current growth rates, while the airport authority argues that the current plans for airports in the Pearl River Delta will also not be able to cope with anticipated demand. It has put forward alternative base proposals for consultation by September this year: maintain the two runway system and develop the existing terminal structure; or build a third runway and associated passenger and apron facilities.

Cathay has put its weight behind the proposal for a third runway. This will involve a significant further amount of land reclamation, but, without a third runway Cathay would have to revisit its fleet plan towards the end of this decade and, despite earlier indications to the contrary, might even consider the need to look to acquire some A380s to accommodate growth on congested routes.

| In service | Orders Options | LOI | Storage | Total | ||

| 747-400 | 21 | 21 | ||||

| 747-400F | 21 | 21 | ||||

| 747-800F | 10 | 14 | 24 | |||

| 777-200 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| 777-300 | 34 | 24 | 4 | 62 | ||

| A320 | 11 | 11 | ||||

| A321 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| A330-300 | 46 | 20 | 1 | 67 | ||

| A340-300 | 11 | 3 | 14 | |||

| A350-900 | 32 | 10 | 42 | |||

| Total | 155 | 86 | 24 | 4 | 9 | 273 |