Virgin Atlantic: Behind the impressive 08/09 results

Jul/Aug 2009

Virgin Atlantic Airways posted impressive results for its 2008/09 financial year – and far better than bitter rival BA – but a closer look at the few figures that are available from the airline indicates that the situation may be very different to the optimistic sheen that Richard Branson and others are putting on it.

As a private company, Crawley–based Virgin Atlantic does not have to reveal most of the details a listed company has to, and what it does release tends to be the very minimum it has to make available under UK law. There’s nothing wrong with that of course, but it does make it almost impossible to analyse the true financial situation of the airline.

Because of that paucity of information, it’s understandable that much of the UK press took Virgin Atlantic’s bullish statements about its 2008/09 financial results (covering the 12 months to the end of February 2009) at face value, and most particularly the apparent over–performance compared with BA’s recently–released figures for its 2008/09 financial year.

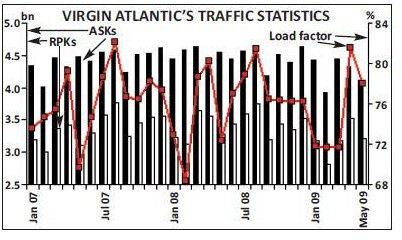

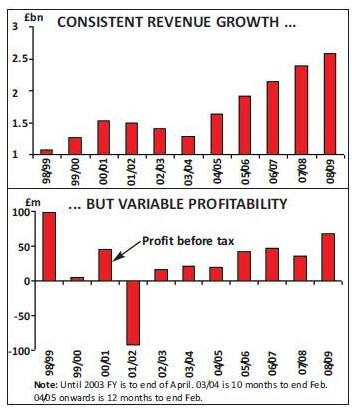

In the 12 months to end of February 2009, Virgin Atlantic (which also includes tour operator Virgin Holidays) posted an 8.4% rise in revenue to £2.58bn ($4.57bn), with pre–tax profit reaching £68.4m ($121.1m) — compared with £34.8m in 2007/08 — and net profit of £45m, down just 6% on the previous 12 months. Passengers carried in the 12–month period rose by 70,000 to 5.77m, and overall load factor rose by around 2% to 78%, according to the airline.

Virgin Atlantic says the result is due to an increase in premium–class passengers and tight management but, before Aviation Strategy looks at the strategic and operational direction of the airline, a few points have to be made about the figures just released.

- GAAP versus IFRS. Virgin Atlantic’s figures have been prepared under the UK’s GAAP accounting rules (which it can legitimately do as it is not a listed company), rather than the international financial reporting standards (IFRS). There are a number of areas where large differences can occur in the two standards, not least in the reporting of derivatives — fuel and currency hedging losses have to be reported under IFRS, whereas in GAAP they are not taken onto published financial results. Worryingly, statements from the Singapore Airlines group — a 49% shareholder in Virgin Atlantic — imply that under IFRS Virgin Atlantic’s results would be very different from those stated under GAAP. In its figures for the three–month period to end of March 2009, the SIA group said its associated companies had lost US$73m, with one SIA executive saying that this was “largely coming out of our investment in Virgin Atlantic”. Altogether SIA says its stake in Virgin contributed just US$0.3m in profits over the full 12–month period to the end of March 2009, which means that Virgin Atlantic barely broke even under IFRS standards. Over the last couple of years Virgin Atlantic has become more aggressive in fuel and currency hedging, and fuel costs rose “just” £300m in 2008/09 year, to £1bn, which implies the hedging strategy has worked in that period. But there is a huge difference between the GAAP and IFRS numbers, so potentially there are costly unclosed derivative positions left for Virgin Atlantic.

- Financial year end. SIA’s statements about Virgin Atlantic’s relative performance in the full 12–month period and the three months to end March directly imply that Branson’s airline had a very poor January- March 2009 period. But Virgin Atlantic’s financial results just released only cover the 12–month period to the end of February 2009, and so if Virgin Atlantic’s performance is getting steadily worse as the year goes on, it has avoided reporting a poor March (everyone else reported a terrible March) by the fact that its financial year ends at the end of February. Of course this also makes a comparison with BA’s results – which do include March 2009 – even more unfair.

- Exceptionals. The GAAP figures provided by Virgin Atlantic include exceptionals that varied widely year–on–year. The £34.8m figure for pre–tax profits in 2007/08 is after exceptionals of £26.1m (largely provisions for potential losses on the fuel surcharge collusion case), while the £68.4m pre–tax profit figure for 2008/09 includes £15m from asset sales. Looking at a better measure, operating profit from continuing operations only — excluding exceptionals — fell year–on–year by a hefty 42%, from £44.4m in 2007/08 to £25.9m in 2008/09. And that £25.9m figure would have been a significant loss but for the fact that Virgin also benefited from a £68m non–exceptional “gain” from dollar–denominated cash balances.

Putting aside the smoke and mirrors of Virgin Atlantic’s accounts, is the airline’s underlying business model sound? Virgin Atlantic says that its apparently improved GAAP figures were due largely to an increase in premium passengers, with the 1% rise in premium traffic in the 12 month period stimulated primarily by fare reductions.

More than premium...

That is in stark contrast to the reduction in premium passengers at BA, and there does appear to be a qualitative difference between the premium passengers carried by Virgin Atlantic and its main rival. BA has traditionally had a far greater reliance than Virgin on financiers and bankers crossing the Atlantic (thanks partly to its better global network); while that has been a strength when the economy has done well, it is a market that has been one of the hardest hit by the current recession (with a resulting disastrous effect on BA’s latest results). In contrast, Virgin’s premium passenger base is far more widely distributed between business sectors, and particularly among the creative and service industries (which are more attracted to Virgin Atlantic’s brand image than BA’s). In addition, Virgin Atlantic has built up a large slug of the UK public sector market (i.e. government officials and civil servants flying on business trips), which is a relatively robust market even in “credit crunch” times. But it would be wrong to overemphasise the importance of the premium story. Plans announced by Virgin Atlantic back in 2007 to launch all–business class services between the US and Europe in 2008 have obviously come to nothing (Branson now calls those ambitions a “mistake”), and one analyst believes that the GAAP increase in post–exceptional profit in 2008/09 is probably due more to cost–cutting than to any great increase in premium passenger revenue.

Indeed Virgin says that it saw tough times coming as far back as 2006, and then began deferring deliveries scheduled for 2007 and 2008. The fleet currently stands at 38 aircraft (see table, left), with six A380s on order, for delivery from 2013, as well as six A340–600s and 15 787s. But Boeing’s delivery delay on the 787 forced Virgin Atlantic to look for capacity from 2011 onwards, to fill in the gap before the 787s are delivered, and at the end of June the airline announced a deal for 10 A330–300s. Four A330s are to be leased directly from AerCap, and six others will be bought initially from Airbus and then sold to and leased back from AerCap. Five of the aircraft will be delivered in 2011 and the rest in 2012, though it’s understood the leases will be for 12 years, providing capacity way beyond that needed as an interim until the 787s arrive. Virgin says the aircraft will be put onto new routes to Shanghai, Cancun and Vancouver. Virgin Atlantic is also reportedly talking with Airbus about an order for A350s. These would replace 747s and potentially even the 787 order, given that a figure of 50 aircraft is being mentioned.

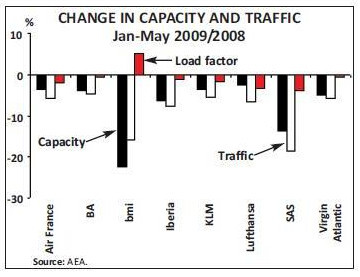

In the shorter–term Virgin is cutting between 7% and 10% of its capacity in the 2009/10 financial year (i.e. the 12 months to the end of February 2010) compared with 2008/09. Around 7% has already been taken out, most particularly on routes to New York, Washington and the Asia/Pacific region.

For example Virgin closed its London Heathrow–Mumbai route in May, instead replacing it with a code–share with Jet Airways, which has a twice–daily service between these cities. Virgin still operates a Heathrow- Delhi route but closed the Mumbai service due to what it calls “irrational overcapacity”; the airline competed against BA, Jet Airways, Kingfisher Airlines and Air India on the route.

However Virgin will add capacity on some routes, such as from Manchester to Barbados and Orlando (after bmi and BA pulled out of long–haul services from the airport). And a weekly London Gatwick to Puerto Rico route (via Antigua) will be launched in November, which will join the existing Caribbean routes to Barbados, St Lucia, Grenada, Tobago, Havana, Montego Bay, Kingston and Jamaica. Altogether Virgin currently operates to 28 destinations from London Heathrow, London Gatwick, Manchester and Glasgow – nine US and eight Caribbean destinations, as well as four in Africa, five in the Asia/Pacific region, and one each in the Indian Ocean and the Middle East. Virgin Atlantic is examining potential routes to South America, Canada (Canadian routes were closed back in 2001) and various Asia/Pacific destinations (thought to include China and Thailand), but any more new routes in 2009 are unlikely. Indeed in July Virgin said it would suspend its Heathrow–Chicago route in winter 2009/10.

The other major cost effort by Virgin Atlantic has been on labour. In February the airline announced it would cut up to 600 positions in 2009, equivalent to 7% of its workforce as at the start of the year (which totalled 8,500). Virgin Atlantic also imposed a pay freeze for all staff during 2009, though this was somewhat eased by the fact that 10% of the GAAP pre–tax profits are now being distributed to staff as a bonus this year, equivalent to one or two week’s extra pay. However in July the airline said another 600 positions could go this year (bringing the total to 1,200), which prompted Jim McAuslan, head of BALPA (which represents 90% of Virgin’s pilots) to say the union would “pressure–test” the need for these cuts. Industrial action is not out of the question, with one employee saying: “The moral leadership at the top of this company is non–existent; the very day they were boasting about their profits they were making people redundant.”

Another front in the effort to improve results is the attempt to offload Virgin Nigeria, the Lagos–based airline that was launched in 2005 and which currently has a fleet of six aircraft. Virgin Atlantic owns 49% of the airline but since last summer Virgin Atlantic has been trying to sell this as Virgin Nigeria’s results have been dragging down the group figures. Virgin Atlantic now regards the airline as merely a regional player rather than a carrier that can provide feed into other Virgin airlines. Virgin Nigeria closed down long–haul routes to the UK and South Africa (which had used leased 767s) at the start of 2009 in the face of fierce competition, and it has also been in a serious dispute with the Nigerian government on access to terminals at Lagos airport. In short, while Nigeria is a tough market, Virgin Nigeria simply hasn’t turned into the African long–haul airline that was envisaged a few years ago, and this must be seen as a strategic failure for Virgin.

Yet serious buyers for Virgin’s stake look thin on the ground. The Nigerian–based United Bank for Africa (UBA) owns 7.5% of the carrier and is reported to want to buy the entire carrier, but the other Nigerian investors are believed to be resisting the bid. Potential buyers may be put off by the fact that Virgin Nigeria needs to raise more capital (at least $200m, which the airline had been trying to raise via a private placement) in order to help pay off what are believed to be high levels of debt. But in any case the Virgin brand will disappear from the airline in July, even before a new owner is found.

At least the Virgin empire’s other forays into global airlines have been more successful than Virgin Nigeria. Domestic carrier Virgin America — though still at a very early stage — is growing, while Virgin Blue (which also owns New Zealand–based Pacific Blue and 49% of Samoan–based Polynesian Blue), finally launched its long–haul subsidiary — V Australia – in February.

Branson has long wanted to create a raft of successful Virgin airlines around the world and says he would like the existing carriers to “integrate as best we can”, but that may not be so easy. The CEOs of Virgin Atlantic, Virgin Blue and Virgin America met in April this year to discuss areas for co–operation, which include everything from logos, sales and marketing to joint aircraft ordering, but all that seems to be happening at the moment are some efforts towards a linked FFP and combined “around–the–world” fares.

Elsewhere, Branson had previously been keen on launching an airline in India, but this idea seems to have drifted away given the major upheavals happening in the Indian market (see Aviation Strategy, December 2008). The Virgin group is also believed to be looking at potential new airlines in South America (Brazil in particular) and Russia, but the realistic short–term imperative for Branson must be to secure short–haul feed into Virgin Atlantic at London Heathrow.

With the purchase of bmi by Lufthansa finally going through, following a last minute agreement between Sir Michael Bishop and the Germans on the steps of the UK High Court, all prospects for a merger between Virgin and bmi have evaporated. In reality, such a merger was always a remote prospect, not because of the supposed antagonism between Branson and Bishop but because adding a limited and heavily loss–making European network to Virgin’s generally profitable, point–to–point long–haul network did not make sense.

Lufthansa is now engaged in the process of trying to sell off bmi’s Heathrow slots and Virgin might appear to be a prime candidate. But the global traffic downturn and the impact of US–EU open skies has probably reduced its appetite for investing in new slots. Would there be any logic in a Virgin/Lufthansa alliance or joint venture? Again, though rumoured, this is a highly unlikely development. Lufthansa’s experience with the Swiss takeover has demonstrated that, with the correct local legal structure, directly owning a locally based airline is not required in order to operate ex–EU from Heathrow. Moreover, Lufthansa is not going to repeat SIA’s mistake in taking a minority position with no effective influence, let alone control, over Virgin.

Virgin Atlantic’s current strategy is all about slowing down capex, preserving cash and keeping revenues up through the bad times. But Steve Ridgway, the chief executive of Virgin Airways, warns that the airline will not make a profit this year, although cleverly this was wrapped up in a statement that no major airline will make a profit this year because of the decline in premium traffic.

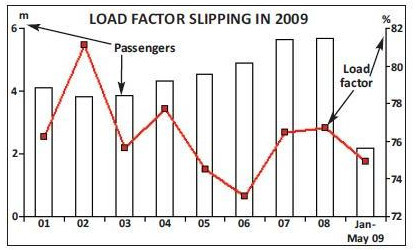

A further clue to the tough year facing Virgin Atlantic is the fact that it says that unlike BA, where traffic began to drop off in July last year, Virgin managed to keep traffic levels up right until November 2008 — from when they started to drop. Assuming that this drop in traffic will not recover substantially before the end of the current financial year, Virgin Atlantic is likely to plunge into a large loss in 2009/10, whether by GAAP, IFRS or indeed any accounting standard it chooses.

Cash is king

The debt and cash position for Virgin Atlantic will be critical, and of course there is an inextricable link between Virgin Atlantic’s financial situation and the rest of the Virgin businesses, given that Branson’s Virgin Group owns 51% of Virgin Atlantic Airways, and historically Branson has often tended to fund many of his businesses with cash generated from his other ventures.

Just how much cash the Virgin empire has is impossible to tell, again because of the offshore and/or private nature of most of the Virgin businesses. What we do know is that Virgin Atlantic had cash reserves of £838m as of June 2008 (it did not release any information about its cash position as at the end of February 2009), and that a stated aim of the airline is to preserve (whatever) its current cash position is. But a recent comment from Branson that he hadn’t ruled out a bid for BA was met with incredulity by most analysts.

If there is a cash squeeze, it’s no wonder that signals from Virgin Atlantic that it would team up with other airlines and make a bid for London Gatwick came to nothing, although not until after a curious incident when Virgin Atlantic claimed it was in discussions with easyJet over a bid for Gatwick — a claim that easyJet immediately and vehemently denied.

Again, without a published balance sheet it’s impossible to know how much debt Virgin Atlantic is carrying. Every now and again Virgin Atlantic executives say they are interested in floating, although there are no plans in the short- or medium–term and therefore no likelihood of analysts being able to examine the airline’s accounts in depth.

Unsurprisingly, Virgin Atlantic continues to lobby against antitrust immunity for the transatlantic joint venture between BA, American Airlines and Iberia. Virgin says that it would lead to higher fares and Branson admits it “would obviously affect our revenue”. Branson also says that he can’t “guarantee Virgin Atlantic’s survival" if antitrust immunity is granted to his competitors, but that is obviously bluster. His serious point is that competition on Heathrow–US would be reduced: Virgin Atlantic says that BA and American have an 80% market share of passengers on LHR–Boston, 73% on LHR–Miami, 64% on LHR–New York JFK, and 64% on LHRChicago (although if BA/American did raise fares then surely this would be beneficial to Virgin Atlantic?). Virgin also serves US leisure destinations from London Gatwick — a lower yielding but also lower cost operation. At least the row between the two airlines will be over soon, as the US DoT will rule on the BA/AA/Iberia application for antitrust immunity by October.

Perhaps the best judge of Virgin Atlantic must be the one entity that should have clear sight of how the carrier is doing – Singapore Airlines. It remains unhappy at the performance of Virgin Atlantic and is still open to offers for its 49% stake, which it bought back in 2000 for US$975m. SIA’s “under–performing” investment – to quote SIA CEO Chew Choon Seng – is likely to have a very tough 2009, so buyers for SIA’s stake are going to be very thin on the ground.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

| A330-300 | 10 | ||

| A340-300 | 6 | ||

| A340-600 | 19 | 6 | 13 |

| A380-800 | 6 | 6 | |

| 747-400 | 13 | ||

| 787-9 | 15 | 8 | |

| Total | 38 | 37 | 27 |