Jet and Kingfisher: Fierce rivals forced together

December 2008

After three years of frantic expansion in the Indian aviation industry, the combination of a weak domestic economy, market overcapacity and rising fuel prices that have forced fares to rise (and domestic demand to shift back to rail) has led to a crisis for India’s airlines. In response, fierce rivals Jet Airways and Kingfisher Airlines are forging an unexpected strategic alliance — but will this be enough for these carriers to survive?

As Praful Patel, the Indian civil aviation minister says, the country’s aviation industry is undergoing its "worst–ever phase", with many analysts forecasting that the country’s airlines will make net losses of around US$2bn in the 2008/09 financial year (ending March 31st 2009), compared with an estimated $1bn loss in 2007/08 and a $0.5bn loss in 2006/07.

The underlying cause of the crisis is straightforward: overambitious expansion since 2004, when the government began to liberalise the aviation industry (see Aviation Strategy, December 2003 and June 2007). Since then, new airlines have been overly aggressive in ordering aircraft and throwing capacity into both the domestic and international markets in an attempt to win market share. Between them, Boeing and Airbus have delivered an estimated 60 new aircraft a year into India over the past three years, and additional capacity has come from a large number of leased aircraft. This extra capacity has been split between international and domestic markets, but the biggest problem is in the domestic sector, where a fleet of around 300 aircraft is estimated to be around 50 to 60 aircraft too large for current domestic demand, according to one analyst. Although both Airbus and Boeing remain — as ever — optimistic about the long term future for Indian aviation (with forecasts of 1,000 new aircraft over the next two decades), the reality on the ground today is very different.

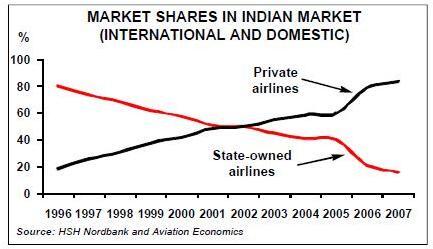

Naresh Goyal — the founder and chairman of Jet Airways — points out that the basic problem that virtually all Indian airlines face is that their costs are still higher than their revenues. That has been conveniently overlooked in the growth phase of the last few years (when the market share of private airlines has risen substantially — see graph) but airlines now realise that this has to change, particularly with fuel costs rising. Practically, that has meant raising fares and fuel surcharges, but this has stifled demand.

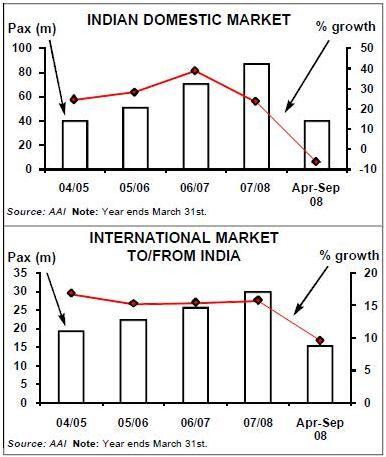

According to statistics from the Airports Authority of India, in the April–September period there were 15.3m international passengers to/from India — 9.5% up on the same period in 2007 — but domestic passengers totalled 39.4m, some 6.7% down on April–September 2007 (see charts). Load factors on many domestic services are hovering around 60–65% as a substantial switch back to cheap rail travel has occurred. Ironically, the state–owned rail company has been hiring ex–airline cabin crew in order to run more service–oriented train services.

The big alliance

Although there has been an estimated 10% reduction in the Indian fleet over the last few months through the grounding of aircraft, that is simply not enough, and Goyal says the industry has overcapacity of 30%. With demand continuing to fall the only option left for India’s airlines is to cut costs, merge and consolidate. Airline consolidation began in 2007, but the speed and depth of consolidation that has happened in 2008 has surprised many observers. But are the mergers and alliances that occurred this year a sufficient response to today’s market conditions in India? In October 2008, Jet Airways — the biggest domestic carrier — and Kingfisher Airlines (the second–largest domestic airline) agreed a strategic alliance. The move was largely unexpected as these airlines have been fierce rivals, but it underlines the crisis that the Indian aviation industry is going through.

Jet and Kingfisher employ 19,000 between them, and they aim to save $200m a year in joint costs thanks to the alliance. The details are still being worked out, but Kingfisher and Jet are looking to save costs in almost all areas, including fuel management, ground handling, FFP, GDS, cross–utilisation of crew, code–sharing, network rationalisation and cross–selling.

Jet Airways

Together, Kingfisher and Jet have an estimated domestic market share of between 55%-60%, and while the government is holding an enquiry into the alliance, Goyal says that the airlines had no choice but to align, since if they had not done so then both carriers would "have gone bankrupt". Mumbai–based Jet Airways was launched in 1993 and is the biggest private airline in India, carrying 11.4m passengers in 2007. It operates to more than 40 domestic destinations and 19 international destinations, the latter including New York, London, Brussels and Toronto.

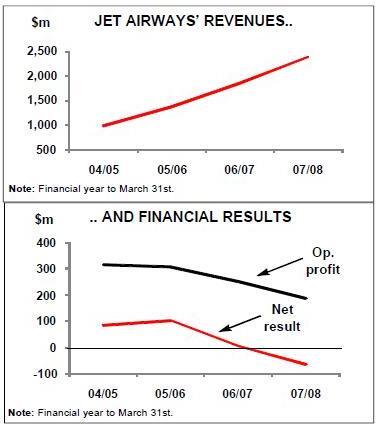

In the year ending March 31st 2008 Jet Airways recorded a net loss of Rs 2.5bn (US$63m), compared with a Rs280m ($6.4m) net profit in 2006/07, despite a 28% rise in revenue to Rs 94bn ($2.4bn) in 2007/08. In the first–half of the 2008/09 financial year (April–September 2008) Jet Airways made a net loss of Rs 2.4bn ($56.2m), compared with a net profit of Rs 592m ($14.9m) in the same period of 2007/08, despite a 45% rise in revenue to $1.3bn.

That’s Jet’s worst half–yearly result in three years, and is due primarily to the costs of international expansion. International routes accounted for 52% of all Jet revenue in the last reported quarter (July–September 2008) — compared with 31% a year earlier — but they made a pre–tax loss of Rs 4bn ($86m) in the three month period, and 50% of that was contributed by just two routes: Amritsar–London and Mumbai–Shanghai- San Francisco.

That was a huge blow to Jet, as international strategy was central to its strategy over the next few years. Jet currently offers services to the Asia/Pacific region, Europe, the Middle East and North America (New York JFK, Newark, and Toronto), but after a Bangalore–Brussels service was launched in October this year Jet now says that it has no plans for any new international routes "in the near future".

At the same time, Jet has suspended or reduced services on several international routes. For example, Jet’s Mumbai- Shanghai–San Francisco service (using 777–300ERS) will close in January 2009, just seven months after it was launched. Jet had long wanted to begin such a service, but after finally winning approval from the Chinese government it found that demand has not been sufficient to keep the service going, although it will code–share on the route via a partnership with United. Elsewhere, Jet is also closing its Amritsar- London route.

This all means that Jet has excess longhaul capacity, and widebody deliveries have been postponed for at least 12 months — although as yet no orders have been cancelled. Jet Airways has fleet of 85 aircraft (which have an average age of less than five years) but more than 50 outstanding orders (see table), including 10 787s.

Jet’s international plans have undoubtedly also been hit by the postponement earlier this year (after a fall in the Indian stock market) of a $400m rights issue that would have funded international expansion.

To compensate, Jet is carrying out extensive cost cutting and network rationalisation, but in October the airline became the subject of fierce criticism after sacking and then reinstating 800 staff within just a couple of days. Jet had wanted to lay off 1,900 (out of a total workforce of 12,666), but after the first 800 (mostly cabin crew based in Mumbai) were made redundant the airline faced protest from staff and politicians alike.

The planned job losses (announced days after the alliance with Kingfisher) were quickly reinstated after Naresh Goyal claimed that he did not know of the sacking of his airline’s staff. Goyal said once he found out he changed the decision, as he could not stand to "see tears in their eyes". The reinstated employees reportedly agreed to take reductions in pay or to forgo salary rises.

Jet’s share price has fallen by 75% in a year, and — in an attempt to set a new direction — in October Jet Airways appointed a new group CEO: Ravi Chaturvedi, who previously spent 25 years with Proctor and Gamble across the world. But he has little option other than to keep cutting costs. Already Jet has cut capacity in its winter schedule by 15%, and while Jet believes domestic Indian market will bounce back quicker than international demand, a few weeks prior to the temporary dismissal of the Jet employees JetLite — its LCC subsidiary — had already made 800 people redundant.

Kingfisher Airlines

Additionally, in October Jet Airways started code–sharing with JetLite on domestic routes, even though the airlines target slightly different markets. Jet bought Air Sahara in April 2007 and changed its name to JetLite, thereafter giving it a low fare focus, but JetLite made a net loss of Rs2.73bn ($64m) in the July–September 2008 period. Mumbai–based Kingfisher Airlines was launched in 2005 by conglomerate United Breweries Holdings (owned by businessman Vijay Mallya), with the airline taking its name from the group’s well–known beer brand.

Kingfisher carried 5.2m passengers in 2007 and operates to more than 40 domestic destinations. It targets both business and leisure passengers, and its mainline operation offers a "premium service" that includes frills such as in–flight entertainment. Its low fare unit is based on LCC Air Deccan (India’s first LCC, which launched in 2003), into whose parent (Deccan Aviation) Kingfisher merged earlier this year.

Kingfisher had previously bought a 26% stake in Bangalore–based Deccan Aviation in June 2007, which was raised to 49% later that year before a merger was carried out in the summer of this year, after which the Deccan name gradually disappeared. Kingfisher was previously in private hands but Deccan was already listed on the Mumbai stock exchange, so the "new" Kingfisher (now that the Deccan brand has gone) is a quoted company.

In September the low cost operation was rebranded as Kingfisher Red, although it then started to offer some frills — such as free on–board meals" — in an effort to differentiate itself from other LCC competitors, and specifically its largest LCC rival, IndiGo Airlines.

That rebranding came as Kingfisher released results for the first half of its 2008/09 financial year (April–September 2008), with net losses of Rs 6.41bn ($150m), 50% higher than the net loss recorded in the first half of 2007/08, despite a tripling of revenue to Rs 27.2bn ($637m) thanks to the merger with Deccan. Operating loss rose from Rs4.26bn ($106m) to Rs7.1bn ($166m) in the first six month of the 2008/09 financial year, thanks primarily to a massive increase in costs. Capacity fell by 4% in the period (with two aircraft returned to lessors, with negotiations continuing for the return of another eight aircraft), although this didn’t stop load factor falling even further, by 6%.

Vijay Mallya, chairman and CEO of Kingfisher, says that the airline will now break even in 2010 (rather than 2009, which had been the previous target) and in September Kingfisher said it was looking to sell debt or equity in order to raise funds of up to $400m. That injection is much needed (an IPO has been planned since 2006, but has just not been possible) as Kingfisher needs to fund a hefty 73 aircraft on order, and although its conglomerate owner is wealthy it will not want to fund a cash drain for ever.

In 2005 Kingfisher placed orders for A330s, A350s and A380s in anticipation of international expansion in 2008; the airline could only operate international routes from August 26th, five years after Deccan was launched (since the Indian government rule is that international routes can only be launched after an airline has operated domestically for five years).

Kingfisher ordered five A380s in 2005, due for delivery from 2011, and the first of five A350s on order are due to arrive in 2014. There are 15 A330s on outstanding order as well as three A340–500s, with five A340–500s delivered to Kingfisher in October.

The first international route began in September, with a service between Bangalore and London Heathrow, with Kingfisher claiming that as it is a "five star airline" it offers offer better service on the route than rival British Airways. It has two–class service in the route: economy and "Kingfisher First", which is a superior business service prices close to a first class product at fares "slightly higher" than standard business class services.

As the new long–haul aircraft arrived Kingfisher had been set to launch many more routes, to Europe, North America (e.g. Bangalore–San Francisco) and the Asia/Pacific region, and as recently as July Kingfisher was planning to operate routes to 13 countries by October, using A320s, A330s and A340s, with Mallya then saying that "we want to expand quickly as yields are better and tax is lower on international

However, in the new realities of the Indian aviation industry and due to the "global economic environment", Kingfisher has now postponed this massive international expansion for at least 18 months. Although the Bangalore–London Heathrow route will continue to operate, no other service is to be launched in this period other than a Mumbai–London route (which starts in January 2009) — and this has meant a frantic reshaping of the order book.

Most A320s that were due to be delivered this year and 2009 have been deferred and other aircraft — such as three recently delivered A330s — are grounded. Two of the A340s on order have already been sold, to Nigerian airline Arik Air, and altogether Kingfisher has already reduced its capacity by 20% since the summer and will dispose of another 10 aircraft over the next year as leases expire.

Domestically, the pre–merger Kingfisher and Deccan had overlapped on 49 routes, but that has been reduced to 14 routes in the current winter schedule, mostly by Kingfisher cancelling around 100 flights a week on around 50 routes. Kingfisher is now concentrating on the Mumbai–Delhi trunk route (where Deccan flights have been reduced), and is also phasing out its fleet of nine leased 42–500s.

Kingfisher had already launched a major cost–saving programme following its integration with Deccan, and so far has trimmed $1m a month from costs, including the laying- off of 300 non–operational staff laid off in August. Other measures include Kingfisher ceasing to paying travel agents a 5% commission (along with other Indian airlines) from November.

However, redundancies of pilots and cabin crew are difficult (if not impossible) to implement, even though — for example — it has a surplus of pilots, estimated to be at least 100, who had been trained up on A330 and A340s ahead of the airline’s planned international expansion, but who are now on full pay and unable to fly.

Merger?

Kingfisher has therefore has to resort to other measures, including a 90% cut in the salaries of newly–trained pilots, while 30 pilots who flew A340–500s have been reassigned to fly A320s, with an accompanying downgrading of salary and seniority. And in December Jet cut salaries for all senior executives by 25%, while all other employees with salaries greater than $18,000 per annum will face gradual cuts in pay over the next 12 months. Given the difficulties that Jet and Kingfisher face, its no surprise that the unexpected alliance between these airlines is leading to speculation that the next step could be a merger.

That would be a logical move, since while the current state of panic in the industry may be overdone, the fundamental problem that India’s airlines face — that demand for air travel is very elastic (being much more price sensitive than, for example, leisure markets in Europe) — remains.

Kingfisher would like to sell a stake to foreign airlines, although currently this is not allowed by Indian law. Mallya wants the government to allow foreign airlines to hold up to 25%, and he says that he has had "expressions of interest" from carriers abroad. Meanwhile in November Jet refuted reports that it was trying to sell a 10% stake to Temasek Holdings, the investment vehicle of the Singapore state.

And there is another problem looming for Jet in particular. LCC Air Asia launched routes to destinations in India this December, with nine routes planned linking India with Air Asia hubs in Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand. Fares are expected to be lower than any currently existing in the market, and this may be the final impetus that forces Jet and Kingfisher to look at even closer ties than they are currently exploring.

Substantive help from elsewhere is unlikely, although India’s airlines have appealed to the government for financial assistance. In July the Indian government set up a committee to examine the financial crisis affecting the aviation industry, although so far the government has refused demands to pump $1bn into Indian airlines via an interest–free three–year loan. Praful Patel recently said that the government is examining ways of assisting Air India as it "is obliged to help" (the government owns 100%), whereas it "is not as obliged to help private carriers".

Instead, the government is concentrating on other support, such as reducing landing fees and cutting tax on fuel. Fuel costs around 50%-70% more to buy in India than in other Asian countries and it is estimated that this burdens Indian airlines with between $1bn-$2bn a year of additional costs. India’s airlines owe an estimated $650m to state–owned oil companies and while an appeal by the industry for relief (via a $1bn loan) over this bill has been turned down by the Indian government, in October the government did agree that India airlines could pay outstanding fuel bills in instalments until March 2009. Additionally, after that date, future fuel bills will only have to be paid within 90 days, rather than the current 60 day period — but all these measures came with the proviso that in return airlines will not make any large–scale reductions in employees.

India’s airlines want a similar scheme for outstanding airport duties, but this has been refused so far, although in November the Indian government also abolished the 5% import duty on jet fuel, which along with the general fall in fuel prices gives an important boost to Indian airlines.

Whether this support is enough remains to be seen, and it may well be that the only alternative to bankruptcy for many of India’s airlines is a further round of consolidation. Rumours swirl about the fate of the smaller private Indian airlines — IndiGo Airlines (which has 20 aircraft), SpiceJet (12) and GoAir (eight) — and it is likely that these will be swallowed up by Jet or Kingfisher in due time. Whatever happens, it’s inevitable that 2009 will see a final bout of consolidation in the troubled Indian aviation industry.

| Kingfisher | Dep. seats | Share | Jet | Dep. seats | Ann | Share | |||||

| Route | Oct-08 | Ann change | K'fisher | Jet | Others | Route | Oct-08 | change | Jet | K'fisher | Others |

| Delhi -Mumbai | 67,466 | 40% | 25% | 20% | 55% | Delhi -Mumbai | 54,462 | -26% | 20% | 25% | 55% |

| Mumbai -Bangalore | 32,859 | 38% | 28% | 26% | 47% | Mumbai -Kolkata | 32,214 | 2% | 45% | 17% | 38% |

| Delhi -Bangalore | 29,660 | 35% | 28% | 28% | 44% | Chennai -Mumbai | 30,832 | 0% | 32% | 18% | 50% |

| Shamshabad -Bangalore | 24,449 | 38% | 39% | 13% | 48% | Mumbai -Bangalore | 30,628 | -25% | 26% | 28% | 47% |

| Bangalore -Chennai | 20,390 | 40% | 32% | 40% | 28% | Delhi -Bangalore | 29,283 | 1% | 28% | 28% | 44% |

| Chennai -Mumbai | 17,143 | 106% | 18% | 32% | 50% | Bangalore -Chennai | 25,486 | 5% | 40% | 32% | 28% |

| Chennai -Shamshabad | 17,074 | 338% | 34% | 11% | 55% | Shamshabad -Mumbai | 22,652 | -13% | 26% | 12% | 62% |

| Shamshabad -Delhi | 12,918 | 55% | 17% | 16% | 68% | Chennai -Delhi | 22,150 | 6% | 31% | 12% | 57% |

| Delhi -Kolkata | 12,772 | 54% | 18% | 28% | 53% | Mumbai -Goa | 21,272 | -5% | 38% | 18% | 44% |

| Bangalore -Pune | 12,750 | 53% | 42% | 22% | 36% | Ahmedabad -Mumbai | 20,504 | -15% | 34% | 11% | 55% |

| Mumbai -Kolkata | 12,258 | 19% | 17% | 45% | 38% | Delhi -Kolkata | 19,829 | -33% | 28% | 18% | 53% |

| Srinagar -Delhi | 10,747 | 167% | 40% | 29% | 30% | Guw ahati -Kolkata | 18,508 | 41% | 38% | 16% | 46% |

| Shamshabad -Mumbai | 10,582 | -15% | 12% | 26% | 62% | Kochi -Mumbai | 15,846 | 7% | 40% | 13% | 47% |

| Shamshabad -Kolkata | 10,323 | -12% | 32% | 15% | 53% | Mumbai -Vadodara | 13,346 | 2% | 68% | 0% | 32% |

| Mumbai -Goa | 10,046 | -19% | 18% | 38% | 44% | Shamshabad -Delhi | 12,149 | -30% | 16% | 17% | 68% |

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

| Jet Airways | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| A330-200 | 11 | 6 | 5 |

| 737-400 | 4 | ||

| 737-700 | 13 | ||

| 737-800 | 33 | 28 | 20 |

| 737-900 | 2 | ||

| 777-300ER | 10 | 3 | 7 |

| 787-8 | 10 | 10 | |

| ATR 72-500 | 12 | 5 | |

| Total | 85 | 52 | 42 |

| JetLite | |||

| 737-300 | 1 | ||

| 737-400 | 2 | ||

| 737-700 | 7 | ||

| 737-800 | 7 | 10 | |

| CRJ200 | 5 | ||

| Total | 22 | 10 | 0 |

| Jet group total | 107 | 62 | 42 |

| Kingfisher Airlines | |||

| A319 | 3 | 1 | |

| A320 | 34 | 24 | 20 |

| A321 | 8 | 4 | |

| A330-200 | 5 | 15 | |

| A340-500 | 3 | 5 | |

| A350-800 | 5 | ||

| A380-800 | 5 | ||

| ATR 42-500 | 9 | ||

| ATR 72-500 | 28 | 16 | |

| Total | 87 | 73 | 25 |