Lufthansa: ready for a major acquisition?

October 2007

The Lufthansa group is set to make more than €1bn of operating profit this year, thanks to cost–cutting, the disposal of loss–making assets, a resurgence of premium bookings and the successful turnaround of SWISS. But will Germany’s flag carrier be satisfied with a steady accumulation of profits, or will the incessant drive to maximise shareholder return tempt Lufthansa into making a major — but risky — acquisition sometime in the next couple of years?

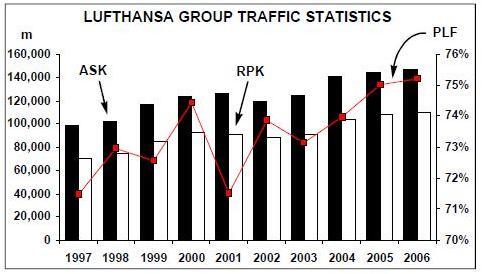

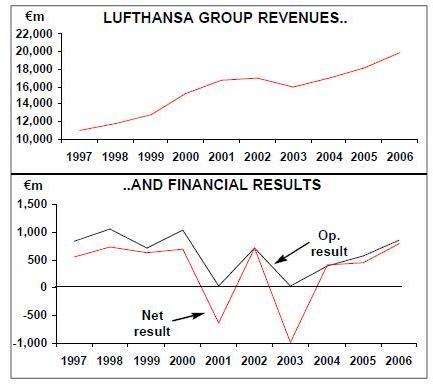

After a poor 2003 (see Aviation Strategy, March 2005), the Lufthansa group has undergone a significant turnaround over the last few years and has increased both operating and net profit in every year since then (see chart). In 2006 group operating profit rose 46% to €845m and net profit rose 77%, to €803m, based on a 4% rise in passengers carried to 53.4m, and a 9.9% increase in revenue.

The upward trend in financial results is continuing, in the first–half of 2007 the group reported a 4.6% rise in revenue, to €10.1bn, with operating profit up 65% to €486m and a significant rise in net profit, up to €992m compared with €85m in the first half of 2006. However, the net figure included a €503m profit from the sale of the group’s 50% stake in Thomas Cook to German retailer KarstadtQuelle (now renamed as Arcandor) for €800m.

The half–year performance has encouraged the group to revise upwards its forecast for full 2007 operating profit to "significantly above" €1bn (reaching as much as €1.3bn, it is believed), but management says that there is still room for improvement, as the stated goal is to become more profitable than its two main European rivals — Air France/KLM and British Airways. That’s still some way off, as Lufthansa’s 2006 operating margin (adjusted for provisions) of 4.9% was well below the 6% of Air France/KLM and the 7.2% of BA.

How much more scope for margin enhancement is there at Lufthansa? To answer that, the group’s overall performance needs to be analysed in its constituent parts. The Lufthansa group now comprises a number of aviation business units, each operating independently, with scheduled passenger airlines grouped together in the "passenger transportation" segment. This segment not only includes mainline Lufthansa but also the regional airlines — CityLine (100% owned by the group), Air Dolomiti (100%), Eurowings (49%), Contact Air and Augsburg Airways — as well as SWISS. In the first–half of 2007 ”passenger transportation” reported a 6.6% rise in revenue, based on a 7.7% increase in passenger traffic, and a doubling of operating profit, to €278m. Passengers carried rose 5.9%, to 27m in January–June 2007, and with capacity rising by 4.6%, load factor rose 2.1 percentage points, to 76.1%.

That’s impressive, but it should be remembered that altogether the airlines contributed just 60% of the group’s total revenue and 55% of overall operating profit. As can be seen in the table, the Technik division (maintenance, repair and overhaul) delivers almost a quarter of group operating profits, while both IT services and the service/financial segment have higher margins than the passenger transport division. Lufthansa has now disposed of the major loss–making part of the group — Thomas Cook — but the overall margin is being dragged down by catering and cargo operations.

Cargo (known as "Logistics" within the group) saw revenue fall by 5.8% in the first half of 2007, and operating profit plunge by almost 40%, due primarily to intense competition and falling yield, particularly on Asia/Pacific routes (where yield dropped 13.1% in 1H 2007). This is prompting the cargo division to switch capacity from the Asia/Pacific region to North and South America routes, but it is too early to see just how successful this strategy is, as other cargo operators are believed to be pursuing the same strategy. In September Lufthansa Cargo announced a 50:50 joint venture with DHL Express, in which a new, unnamed carrier based at Leipzig–Halle will operate a fleet of 11 leased 777Fs from April 2009. Also hanging over the Logistics division is just how much "restitution" it will be required to pay following the investigation by the US Department of Justice over Lufthansa’s role in the alleged global air cargo cartel. While Korean Air and BA have been given hefty fines, Lufthansa is co–operating with US investigators under the DoJ’s leniency policy, but this does not mean that the airline will escape a substantial financial penalty.

Perhaps more of a worry for the group is its catering operation, called LSG Sky Chefs. Although its performance has improved recently, thanks largely to cost–cutting, this segment employs a hefty 30,000 people (the total group employs 97,000), and the return on the capital employed is just not good enough if the group — as a whole — wants to improve its margins to that of its key rivals. Strategically, catering adds little to the group, and it would surely be much more cost and capital effective to sell LSG and outsource the catering needs of the group? An IPO had been planned for LSG prior to September 11, and the unit’s recent improvement presents the group with the ideal opportunity to offload this under performing business.

While fine–tuning of the rest of the group is still necessary, the passenger airlines will continue to be "at centre stage", according to Wolfgang Mayrhuber, chairman and CEO of Lufthansa group. He says that the passenger airlines "are the engines driving the group forward and spurring all other group activities".

| Share of | |||

| Share of | operating | Operating | |

| revenue* | profit | margin | |

| Passenger transport | 59.9% | 55.3% | 3.8% |

| Technik (MRO) | 15.3% | 24.7% | 6.6% |

| Cargo | 11.0% | 5.8% | 2.2% |

| Catering | 9.5% | 6.2% | 2.7% |

| IT services | 2.8% | 2.8% | 4.1% |

| Service & Financial | 1.6% | 5.4% | 14.1% |

Strategic success

The passenger transport division’s strategy is based on the "four multiples" — multiple brands, markets, hubs (Frankfurt, Munich and now Zurich) and product (i.e. three classes).

At the heart of this is a so–called "multi–offer" appeal, offering products and services for every part of the passenger spectrum, from economy to premium. Rather than shoehorn this multi–offer into the mainline Lufthansa, the variety of airlines and brands in the Lufthansa empire target specific customers and markets, and while this may lead to some brand dilution and even customer confusion as to which airline does what, overall the strategy has been very effective.

In the economy segment, in 2005 the airline started offering discounted fares (what Lufthansa calls "taster" fares) of €99 on selected European routes out of Hamburg, with dedicated aircraft stationed there in a new operational model that linked in with improved feed by CityLine into Hamburg, with the regional airline also basing more aircraft at the airport. This increased aircraft productivity at Hamburg by 20%, according to the group, and such was the customer response that Lufthansa expanded what it now calls its "betterFly" fares to all German airports from last year. Accompanied by a major expansion of capacity within Europe, with ASKs up by 7.4% in the first–half of 2007, and this extra capacity and lower fares (together with services from budget airline Germanwings) "betterFly" fares have provided real competition to the LCCs, in particular to Air Berlin.

But Air Berlin, the second–largest airline in Germany, hasn’t been inactive either, and after an IPO in 2006 it accelerated the process of consolidation in Germany. After acquiring Gexx and dba, it bought LTU this year and now intends (subject to agreement by the German regulator) to merge its fleet with Condor in a two–stage share swap in which Thomas Cook will acquire a 29.9% stake in Air Berlin in 2009, in exchange for which Air Berlin will obtain 75.1% of Condor in 2009 and the remaining 24.9% in 2010. This last part of the deal will occur once Thomas Cook has acquired the 24.9% of Condor still owned by Lufthansa, which it is entitled to do by 2009 as long as Lufthansa does not exercise an option it retains to buy back the entire Condor airline now that a buyer has emerged. Lufthansa is contemplating its response to the Thomas Cook/Condor/Air Berlin deal at the moment — tempting as it would be to sink the deal, Lufthansa is unlikely to want to be burdened with Condor. There are now more than 100 aircraft in the Air Berlin group fleet (pre the merger with Condor, which will add another 20–plus aircraft), with almost 130 aircraft on outstanding order.

Ryanair remains an annoying thorn in the side of Lufthansa, with continuing complaints by Ryanair about "state aid" to the German flag carrier through the dedicated terminal Lufthansa uses at Munich airport. Lufthansa has also been battling against Ryanair in the German courts over the latter’s deal with Frankfurt Hahn airport, at which Ryanair has built up a major base that serves more than 40 European destinations.

Despite Lufthansa’s strong counter–attack against the LCCs, the challenge to Lufthansa’s economy business in Europe continues to grow. Yield on the passenger airlines' European routes fell 2.3% in 2006, falling to -5.4% in the first–half of 2007. Strategically, it would be very difficult for Lufthansa to reverse the fare cuts it has been introducing on short–haul, and so the only other answer the group can have in combating the LCCs is to keep up the cost–cutting pressure.

Group annual costs have been reduced by €1.2m over the 2004–2006 period under the so–called "Action Plan" programme, but Lufthansa will have to cut even deeper if it wants to keep some kind of margin on short–haul, given the continuing fall in yield. There is scope for further improvement, as revealed with analysis of Lufthansa’s ambitions in the "Action Plan" and what it actually achieved. In 2004, management targeted €300m of group savings in each of four segments: employees, external suppliers, internal suppliers and "production processes". In fact, both the "production process" and employee cost targets were missed, with the former saving just €208m on an annual basis, and staff just €196m. These shortfalls were made up by higher–than–anticipated cost cuts in the other two areas, but this under–performance in two targeted areas suggests there is scope for further cost–cutting — but only if management is prepared to get tough with unions.

That’s a very big if, because — with some justification — the unions believe they have already given enough concessions away, they see little reason to concede more on pay and conditions with profits rising sharply. In 2006 Vereinigung Cockpit, the union that represents 4,000 pilots at the mainline and cargo business, agreed an 18–month deal with management following the end of a two–year wage freeze. Pilots received an immediate 2.5% pay rise followed by a further 1.5% rise in March 2007, but in return agreed to a gradual reduction of normal working hours before overtime kicks in, which gives the airline greater cost flexibility when seasonal demand is low.

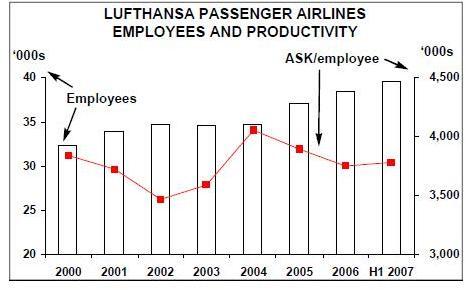

While cost comparisons with earlier years are difficult because of changes in the composition of the group, Lufthansa can be criticised on one key efficiency measure — productivity. As can be seen in the chart, productivity as measured by ASKs per employee in Lufthansa passenger business rose considerably over the 2002–2004 period while employees remained flat at around the 34,500 level and large capacity increases were implemented. However, in 2005 and 2006 productivity plunged as the effect of the rise in the number of employees from new "acquisitions" in passenger business (2,000 staff have been added through the full consolidation of Eurowings, for example) has more than overcome the accompanying capacity increase, and there was only a minor improvement in productivity in the first–half of 2007.

A key problem facing management here is that relations with unions are tricky at present. In July Lufthansa came to an revised agreement with the Ver.di union for 14,000 cabin crew, following disputes in which the union claimed the airline was in breach of a deal only signed last May. The amended deal included an extra 0.9% pay rise for staff on top of the previously agreed 2.5% rise, as well as participation in a profit sharing scheme.

A new clash with Ver.di has broken out, this time at regional carrier CityLine. While Ver.di primarily represents ground workers, it has recruited some pilot members at the regional carrier who are dissatisfied with the actions of the union Vereinigung Cockpit. Ver.di wants to reduce the pay differential between the 750 CityLine pilots and mainline Lufthansa crew, which Jan Kahmann, the head of Ver.di, says on average is around 40%. A deal reducing the differential had been agreed with CityLine pilots represented by Vereinigung Cockpit, but this was rejected by a number of pilots, and those objectors have now become members of Ver.di.

Following stalled talks, minor industrial action took place in August and while the dispute is likely to be settled soon, the atmosphere just does not exist for management — even if it wanted to — to try and obtain any cuts in employee pay and conditions, and in any case the Ver.di union is already warning Lufthansa to abandon its "shareholder–value ideology".

Fleet overhaul

If further employee cost savings are ruled out, there seem to be few other areas of the airline operation with serious cost cutting potential, although the group has launched an "Upgrade to Industry Leadership" programme to identify new areas to trim costs. Lufthansa has already taken out infrastructure costs in Germany under a plan called "Air Traffic for Germany", which has included buying a 9.9% stake in Fraport, the German airport operator. A new service agreement signed with Fraport for the Frankfurt hub will deliver "considerable cost savings in the double–digit millions", according to Lufthansa. One area of future cost improvement will be in the fleet, where lower unit operating costs will result from the massive renewal programme that is currently underway. The mainline fleet currently stands at 244 aircraft (see table, below), but 137 aircraft are on order, which is a reflection that more than 100 aircraft in the mainline fleet are more than 12 years' old. On the back of improving financials, Lufthansa has placed major orders over the last couple of years in an effort to completely overhaul its regional, medium–haul and long–haul group fleet.

On long–haul, an order for five A330–300s was placed in 2006, for 2006- 2008 delivery, while an order for nine A330–300s was placed on behalf of SWISS in September this year, which will replace A330–200s from early 2009 onwards. Lufthansa also became the launch customer for the passenger version of 747–8 in December 2006, when it ordered 20 aircraft and placed options for another 20 aircraft, to be delivered in 2010–2013. Some analysts saw this order as a stop–gap reaction to the delay in receiving the 15 A380s that Lufthansa has on order, and which will now arrive from 2009 onwards, but the airline insists this is not the case, and says the 400–seat 787s are part of the planned overhaul of the long–haul fleet, filling in a gap between the smaller capacity A340–600s (seven were ordered in December 2006) and the 550–seat A380s.

On medium–haul, in September 2007 the Lufthansa board approved an order for six A319s, four A320s (plus two A320s for SWISS) and 20 A321s, which will replace ageing 737s and A320s in the European fleet. 30 other A320s were already on order, for delivery from late 2007 onwards, so the mainline has a total of 60 medium–haul models on order.

Lufthansa group’s five regional airlines operate a fleet of 149 aircraft, but 37 of them are ageing BAe 146s (with an average age of 18 years) and Avro RJs. In June this year Lufthansa ordered 30 Embraer E–190 regional jets, with delivery from early 2009. This order "replaced" an existing SWISS order for 30 E–170s and E–190s, and the 100–seat aircraft will operate in a two–class configuration for the various regional airlines. However, in order to operate the E–190s the Lufthansa group will have to reach new agreements with pilot unions, as current deals restrict its regional carriers to operate aircraft with no more than 70 seats. After agreement with the unions, there is an exception at CityLine, where RJs and CRJ900s are flown, and a deal for the E–190s should be agreed with unions soon. In May last year Lufthansa also ordered 15 CRJ900s (plus purchase rights for 15 further aircraft), which was a confirmation of a planned order by Swissair, and further regional aircraft orders will follow as the 45 aircraft on order are not sufficient to replace the older models currently operated.

Premium success

All these orders mean a sizeable capex by the group over the next few years, although the group’s financial position is healthy. Longterm liabilities and provisions are relatively static, totalling €7.9bn as of the end of June 2007, just €43m higher than a year earlier. Of this, a hefty €3.7bn is for retirement benefit obligations, while there is €2.9bn in long–term debt. Cash flow from operating activities was €1.1bn in the first half of 2007 (54% up on 1H 2006), and cash and cash equivalents stood at €699m at the end of June 2007 (compared with €455m a year previously). With short–haul yield falling and the scope for further cost–cutting reduced, it is on premium customers that the future of the mainline — and perhaps the entire group — really depends, indeed within the "multi–offer" strategy there is a big push in first- and business class that is designed to protect and improve Lufthansa’s overall yield position.

Around half of Lufthansa’s revenue — and a large majority of its profits — on long–haul come from first- and business classes, and the airline says that first–class passengers have risen by more than 20% over the last couple of years. Unlike some of its rivals, Lufthansa has kept a three–class configuration and its decision to keep first–class on all but a handful of aircraft appears to be paying dividends as premium traffic has returned over the last year or so. In fact the airline is reconverting back to a three–class configuration the few aircraft it did change to two–class, and is now fitting more premium seats on aircraft at the expense of economy seats. In May the airline also completed an overhaul of business class cabins in its entire long–haul fleet, while on short–haul more storage room and a free middle seat have been added in the business section. A new first–class cabin is also being developed, and will be introduced across the entire long–haul fleet in 2009, once the A380s start arriving.

In 2005 Lufthansa also introduced a first–class only terminal at Frankfurt, and the airline believes this has been a major factor behind the resurgence in first–class ticket sales. A first–class lounge costing €6m was also opened at Munich airport in August this year, although this time it is within the Terminal Two building, rather than in a separate facility as at Frankfurt. Interestingly, although SWISS and Austrian first–class passengers are allowed to use the facility at Munich, all other Star first–class passengers have to use the business class lounge.

Lufthansa will also open a new first–class lounge at New York JFK early next year, and business lounges at Dusseldorf and Frankfurt are also being upgraded as part of a €100m investment over the next couple of years on premium–class lounges and other ground facilities. For its premium passengers Lufthansa also operates private jet flights in Europe in a joint venture with NetJets that started in 2005. The service operates around 300 flights a month, and after extending the partnership with NetJets for another five years, Lufthansa is now analysing the introduction of onward private jet flights at some of its long–haul destinations in the Middle East and the Asia/Pacific region.

Improvements in the premium product are being accompanied by expansion into markets Lufthansa believes have the best long term potential for premium traffic. Two–thirds of passenger traffic turnover in the first–half of 2007 came from Europe (66%), with North America (15%) and the Asia/Pacific region (14%) accounting for the bulk of the rest. However, the contribution to profits is believed to be the reverse of this, thanks to the high margin premium traffic on the longhaul routes.

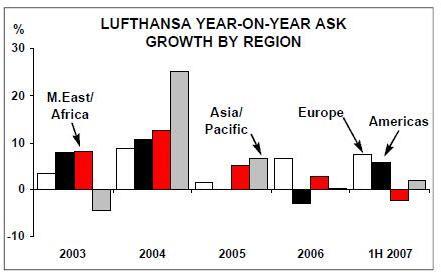

Including code–shares, the North America and the Asia/Pacific regions account for 204 out of 249 long–haul destinations served by the group, and for 82% of all long–haul revenue. After a year or so of static or even negative growth on Americas and Asia/Pacific routes (see chart), capacity growth is starting again on these two sectors. A Munich–Denver route started in March this year, helped by an "incentive package" of $2m given by the local development corporation, while a five–times–a-week service between Frankfurt and Orlando launches in October this year. Other long–haul routes launched or shortly to open this year include Buenos Aires, Busan (South Korea), Karachi and Lahore (the last two restarted after being mothballed for a number of years), while Lufthansa has signed an MoU with Brazil’s TAM over a code–sharing deal (which would help fill in the gap created by the withdrawal of Varig from the Star alliance last January).

The renewed focus on premium was a major reason behind the acquisition of SWISS, in which Lufthansa initially acquired 49% in July 2005. Via a holding company — AirTrust — Lufthansa completed full operational takeover of SWISS in 2006 when the airline was de–listed from the Swiss stock exchange, although the Lufthansa group only acquired 100% legal control of SWISS in July this year, after finally acquiring the required traffic rights. Lufthansa had hoped to fully incorporate SWISS onto its balance sheet in 2006, but the renegotiation of bilaterals (which previously required majority Swiss ownership of the airline with which the traffic rights were agreed) took much longer than anticipated, particularly in Russia, China and India.

The SWISS fleet has now been consolidated, new collective agreements have been signed with unions, extensive cost–cutting has been implemented and SWISS has been integrated with Lufthansa timetables, products and fares. Importantly, the decision to keep SWISS running as a separate brand within the Lufthansa group appears to be very successful. As well as access to a swathe of lucrative SWISS business passengers, the deal fills in a relative weakness in the group’s long–haul network through the addition of SWISS’s routes into Africa. Capacity is now being added on a number of routes (such as to Los Angeles and Sao Paulo), while for the first time since its emergence from the wreckage of Swissair, SWISS is starting to increase its long–haul network, with a Delhi route starting in November and a service to Shanghai from March next year.

Lufthansa says that synergies between the two airlines in 2006 totalled more than €200m, well ahead of the €70m it previously expected. Synergies in 2007 are expected to be €224m, compared with the forecast €156m, of which €120m will come from extra revenue and €104m from cost savings. However, that has to be set against an estimated one–off integration cost of €45m, on top of the purchase price, which in a complicated process will cost anything between €47m and €300m, depending upon the performance of the Lufthansa share price, which is part of a debtor warrant to the former SWISS shareholders.

However, it must be noted that SWISS has structurally high costs due to Switzerland’s high infrastructure and labour costs, and how far SWISS’s unit costs can be reduced through integration with the Lufthansa group remains to be seen. Lufthansa argues that larger average aircraft size, a reduction in turnaround time from 40 to 30 minutes and an optimised hub structure will lower costs at SWISS, but there are certain structural costs at the Zurich hub that Lufthansa simply will not be able to reduce. Nevertheless, the Lufthansa group may believe that this is a price worth paying in order to access the premium customers that are loyal to SWISS. Additionally of course, the deal gives Lufthansa a third major hub to add to Frankfurt and Munich, and Zurich has the key advantage that — unlike most German airports — it has plenty of capacity. Indeed the ease of transiting in Zurich has enabled SWISS to build up a large transit market, with 90% of its traffic going to points beyond Switzerland.

Nevertheless, in the medium–term the Frankfurt and Munich hubs remain the core of the Lufthansa passenger airline network, even despite the capacity problems they face. 78% of all Lufthansa’s traffic currently goes though either Frankfurt or Munich, and the group operates an extensive feed operation into them (60% of CityLine’s flights feed into Frankfurt and Munich, and 90% of Air Dolomiti’s services go into Munich). Of the two hubs, capacity restrictions are more severe at Frankfurt, so Munich will be the focus of most of Lufthansa’s expansion over the next few years. The plan is to build up Lufthansa’s long–haul fleet at Munich to 30 aircraft by 2011, while on short–haul, routes are being expanded to south and east Europe.

Even here though, Lufthansa faces short–term difficulties, as Munich’s second terminal — which opened in 2003 and is dedicated to Star airlines — carried 22m passengers last year, and its maximum capacity is 25m. Although the terminal will be extended in the future to add another 17m passengers a year capacity, no timetable for its building has yet been agreed, so while construction of a third runway is scheduled to begin in 2011, it’s likely that neither an extended terminal nor a new runway will be opened until 2012 at the very earliest, which leaves Lufthansa with a short–term — but potentially severe problem — once the second terminal reaches capacity, which it is likely to occur in 2008 or 2009.

Mayrhuber says that German bureaucracy is getting in the way of Lufthansa’s growth, citing the delays in expanding Frankfurt and Munich airports (as opposed to the rapid development of new airports in Dubai, for example). But given the tight timescales, little can be done about the Munich problem, and the group has little option to develop Zurich and — potentially — open up a third hub in Germany.

Traditionally, the group’s two–hub strategy in Germany has been based on the argument that there is not enough demand at other German airports for direct long–haul flights, and that business passengers are happy to feed into Munich and Frankfurt in order to reach their destinations. But prompted by the capacity problems at its hubs, Lufthansa is having a rethink about this — though sceptics might claim that a bigger incentive is being provided by competitors, who are keen to develop viable long–haul hub competition to Munich and Frankfurt.

US carriers offer a number of routes into other German cities, but it is Emirates that may be causing Lufthansa most concern. It already operates a daily route between Hamburg and New York, and there have been persistent rumours — completely denied by all concerned — that Emirates is interested in buying a stake in Lufthansa (which is believed to have caused upwards pressure on Lufthansa’s share price this summer). At the very least Emirates is interested in increasing capacity into the German market, and it has reportedly asked the German government for permission to operate routes to Berlin and Stuttgart — which would be a direct challenge to Lufthansa’s operations at Frankfurt and Munich.

Under the current air services agreement, there are no restrictions on the number of flights from the UAE into Germany, but there are restrictions on the airports that can be served, which are Frankfurt, Munich, Hamburg and Düsseldorf. Negotiations with the UAE are believed to have begun, and the German transport ministry is reportedly willing to give Emirates permission for the new services, but only as long as it sticks to the current limit for its flights into Germany (63 per week). Whether the German government will be able to agree such a deal with the UAE and maintain the cap on flights into Germany remains to be seen, but Lufthansa knows that sooner rather later Emirates will build up more routes into Germany.

A further concern for Lufthansa is that in August the German authorities cleared the takeover of LTU by Air Berlin. Air Berlin wants to turn LTU into a scheduled airline that targets the business market, and as the two airlines have large operations at Düsseldorf, this will be built up into a substantial operation, with many of the 25 787s that Air Berlin has ordered likely to be based there.

These twin threats — combined with the capacity restraints at Munich and Frankfurt — have undoubtedly prompted Lufthansa’s decision to start building up Düsseldorf as a longhaul airport, and create some competition to its long–haul rivals. Currently Lufthansa stations 30 aircraft at the airport, mostly serving European and domestic routes. The exceptions are services to New York and Chicago operated on Lufthansa’s behalf by PrivatAir, using 48–seat A319s. Lufthansa has now come to the conclusion that the tiny amount of capacity offered by PrivatAir out of Düsseldorf is not adequate, and so the PrivatAir aircraft will be taken out of service in April next year (and will be redeployed to another German city, it is believed).

A troubled future?

In its place Lufthansa will launch A340 services (with a 221–seat, three–class configuration) out of Düsseldorf to the two US cities as well as Toronto. Almost 500 new jobs will be created at Düsseldorf as a result, and it’s likely that further long–haul routes will be added in the future. Three A340–300s will be based at Düsseldorf from next year, and these aircraft will compete directly with services to New York and Toronto operated by LTU. Meanwhile Lufthansa’s other PrivatAir route — from Munich to Newark using a 44–seat Boeing Business Jet — is also being transferred, to operate out of Frankfurt from this October, and will be replaced by a mainline service out of Munich using a three–class A330. The Munich–Newark route was lunched in 2003, but Lufthansa says the Newark service is being transferred to Frankfurt as this has earlier departure times, thus allowing business passengers to get better connections in Newark.While the prospects for full year results are very good, the Lufthansa group faces mounting pressure on yield in Europe, and with relatively little scope for further cost cutting or the sale of substantial non–core assets (apart from the catering business, which management appears reluctant to dispose of), revenue growth looks the main strategic option for the group. Management insists this will be organic, and that there are not any immediate plans for a major acquisition. While there is probably scope for driving more revenue and profit out of the existing airline portfolio, most of the internal synergies are already exploited to their greatest extent, and revenue growth will largely be dependent on signing new partnership deals with other airlines. For example, in July Lufthansa signed an MoU with AirUnion, the alliance of five Russian airlines launched in 2004 (see Aviation Strategy, April 2007). The MoU envisages code–sharing, FFP links and reciprocal ticket selling from 2008 onwards, and will ensure substantial feed for Lufthansa out of Russia, as in 2006 AirUnion carried 4.9m passengers to 35 domestic destinations, making it second only to Aeroflot for carrying passengers in Russia.

Lufthansa operates to almost 20 destinations in the former USSR, and to Moscow alone operates 70 flights a week from Munich, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Düsseldorf and Berlin, carrying more than 0.6m passengers each year. The deal has encouraged Lufthansa to switch its Moscow operation from Sheremetyevo to Domodedovo airport from the summer of 2008, once its current contract with the airport expires. Sheremetyevo airport reportedly offered Lufthansa a long–term contract to remain there, but Domodedovo is not only the prime Moscow hub for AirUnion, but also receives flights from other Star members (including SWISS, bmi and SIA, with Austrian moving its flights there from Sheremetyevo earlier this year). The move will cement Domodedovo at the Moscow hub for Star, where it will compete against operations there by oneworld airlines (with Sheremetyevo left only with SkyTeam flights).

Partnerships with this potential are few and far between, and the Lufthansa group will have to be very creative elsewhere if its wants to increase revenue organically. One area may be long–haul economy. Lufthansa is introducing individual television screens for all seats on long–haul aircraft from November onwards, following the successful trial on selected routes though the summer, but more ambitiously Lufthansa is examining the introduction of all–sleeper cabins for economy class on long–haul. This would entail a bunk–style layout with beds stacked three at a time, and as it is unlikely that these would be convertible into normal seats, this could only be used on routes with overnight flights. The concept is currently being tested with focus groups, but it must be noted that a number of airlines have already taken a close look at beds in economy class, and all of them abandoned the idea because of the amount of space required.

Without an organic revenue panacea, the Lufthansa group is vulnerable to any threat to its long–haul yield, for example during the next aviation down cycle — when premium passengers may fade away yet again — or from competition on long–haul out of Germany. If long–haul yields did fall for any reason, then combined with what will surely be continuous competitive pressure on short–haul, the whole group’s profit base would be under tremendous pressure.

The targets?

A related factor here is that Lufthansa’s shareholder base is slowly changing. Lufthansa is now in danger of breaching the 50% foreign ownership cap, (on which its traffic rights and operating licence depends), and in April the percentage of German shareholders fell to less than 56%. If the proportion of foreign owners keeps rising Lufthansa will be forced into a share buyback of foreign shares, or into issuing new shares to German investors, a complication that the group could well do without. The issue of foreign ownership is sensitive in Germany, and although French insurance firm Axa holds a 10.6% stake in Lufthansa, it is the almost 30% of Lufthansa’s shares in the hands of US and UK investors that unions and some politicians see as potentially leading to the major disadvantage of encouraging an Anglo–Saxon/US short–term investment horizon. At the first sign of any erosion in long–haul yield, the foreign shareholder base at Lufthansa may be less forgiving than the more "friendly" German shareholders of the past, so from a strategic viewpoint the temptation for the Lufthansa group in 2008 may be to pre–empt any trouble on the long–haul yield front by making a major acquisition, or at least a number of medium–sized takeovers. If this happens, who will Lufthansa move for? The "usual suspects" are Iberia and Alitalia, but while Lufthansa has also continually been linked with a bid for the Spanish flag carrier, earlier this year Lufthansa said the Spanish carrier was too expensive (or as Mayrhuber put it, the share price had been driven upwards by bid speculation to a price that was "not affordable" for Lufthansa). Although a last ditch bid for Iberia cannot be ruled out if the BA/Texas Pacific Group bid falls through, it’s unlikely that Lufthansa will make a move for Iberia. Interestingly, Stephan Gemkow, CFO of Lufthansa group, has stated that the group would never want to partner with private equity investors in making a bid for any major airline, as financial investors "do not add value for us".

Debatably, a better strategic fit for Lufthansa would be Alitalia, but — rather sensibly — the German airline has never been a serious bidder for the troubled airline, either previously or currently (now that it is back on the market). Lufthansa claims that the conditions on the sale of Alitalia were too restrictive, though it might look at the option again if conditions "changed dramatically", according to Gemkow. However, it’s likely that Gemkow is being polite towards its close neighbour, given the catastrophic position the Italian flag carrier finds itself in.

If this analysis is correct, then ostensibly Lufthansa would have to turn to a more "medium–sized" target if it decides to go down the acquisition route. As with all major airlines, Lufthansa is continuously linked with a raft of potential targets, and these have recently included:

- Austrian Airlines (possibly delivering substantial cost savings thanks to overlap in the airlines' networks, particularly in eastern Europe — though this deal may be difficult to pull off politically);

- JAT Airways, the Serbian flag carrier that is undergoing a privatisation process; and

- Spanair, which has been put up for sale by owner SAS. Spanish newspapers claim that Lufthansa is analysing a joint bid for the airline along with fellow Star member TAP. Lufthansa calls this story a "rumour", which may be corporate–speak for potential interest in the deal.

Any of these deals would be interesting for Lufthansa and provide some premium feed for long–haul, but they surely wouldn’t deliver any meaningful strategic value to the group, particularly in terms of securing valuable new long–haul routes? And that’s where bmi comes into the reckoning. Lufthansa has a 30% stake (minus one share) in bmi, but now that SAS’s 20% stake in bmi is up for sale, sources indicate the German airline has been in discussion with SAS over the potential purchase of those shares — though Lufthansa, of course, will not confirm this.

Lufthansa, like SAS, has been in partnership with bmi through the European Cooperation Agreement, which was signed back to the late 1990s as a profit–sharing scheme for short–haul operations at the Star alliance. This deal has been nothing short of disastrous, having turned out to be a loss–sharing agreement for both SAS and Lufthansa, and as soon as it expires (on December 31st this year) SAS will sell its bmi stake. While at one point Lufthansa was also tipped to sell its bmi shares, it now far more likely that Lufthansa may buy SAS’s stake, with the key prize being bmi’s 12% share of slots at London Heathrow. In August bmi stated it would use its Heathrow slots for Middle Eastern and African routes in the medium–term, rather than for transatlantic routes, but Lufthansa (or any other potential buyer) would surely find more lucrative uses for those slots. Potentially the 50% plus one share owned by Michael Bishop, the founder of bmi, may also be in play, and Lufthansa would be well positioned to persuade Bishop to sell to it rather than anyone else.

But over and above bmi, there may be other less obvious targets on the horizon. Right now reports are emerging that Lufthansa is in talks looking to buy the 25% stake of LOT Polish Airlines that was owned by Swiss Air.

With a healthy balance sheet, the Lufthansa group is — if it wants to — strong enough to make a play for virtually any of the world’s major airlines, particularly if the other carrier was open to a "merger of giants". A Lufthansa equity tie–up with, say, Emirates or an Asia/Pacific carrier appears unlikely at the moment, but if Lufthansa figures out that this would be the best strategic move, then the unlikely could well become possible.