Aeroflot battles through chaotic times in Russia

April 2007

Aeroflot is starting to post significant profits, but the airline is battling against a shambolic Russian aviation industry and a government owner whose indecision continues to hold back Russia’s flag carrier. Can Aeroflot overcome these external challenges, or is the airline destined to fall back into the ranks of Europe’s niche carriers?

Aeroflot was established in 1923, not long after the end of the Russian civil war, but in 1992 the state airline was divided up into hundreds of regional airlines, with international routes remaining together as Aeroflot Russian International Airlines (ARIA). Later that decade 49% of ARIA was sold to employees, and Aeroflot started building up a domestic network again.

At the start of the current decade its name was modified yet again, to Aeroflot Russian Airlines, and today the airline serves almost 100 destinations in 53 counties around the globe, including 36 in Europe, five in North and Central America, two in Africa, five in the Middle East, nine in Asia and eight in the CIS.

Aeroflot has a 21% share of international traffic to/from Russia and 17% of the domestic market, but international passengers accounted for 62% of Aeroflot’s revenue in 2005, and most of Aeroflot’s profits come from scheduled routes into Europe. Though more profitable, the reliance of Aeroflot on international traffic means "the company is more vulnerable to external shocks", according to one Russian analyst, and a key part of the company’s strategy is to win a much greater share of the domestic market, both in trunk routes and those routes that feed into international services. But perhaps a more important rationale for the domestic push is that Aeroflot wants to build up its position prior to Russia joining the WTO (expected sometime this year), which will oblige the government to open up domestic routes to foreign airlines.

Aggressive expansion began in the domestic market in 2004, and Aeroflot currently serves 25 Russian destinations, but the aim is to grow domestic traffic by more than 20% in 2007 through both new routes and greater frequencies, with a target of a 30% market share domestically by 2010.

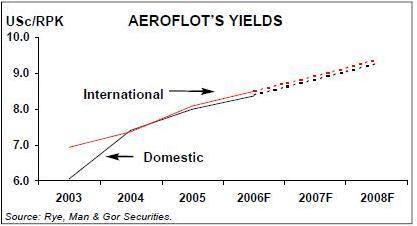

Though Aeroflot’s yield lags behind all its major western competitors, it is improving (see chart, page 12), and according to Deutsche Bank analysis "the growth in domestic routes will not lead to a deterioration in the quality of its revenues, as domestic yields are only marginally lower than international yields."

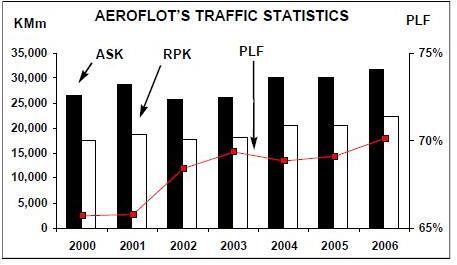

In 2006 Aeroflot carried 7.29m passengers — 8.5% up on 2005, but somewhat short of the targeted 8.3m for the year. Load factor reached 70.1% in 2006 (see chart, page 13), one percentage point up on 2005. Excluding its wholly–owned regional subsidiary Aeroflot- Don, mainline Aeroflot carried 6.7m passengers in 2006, which is identical to the 2005 figure. Aeroflot is aiming for 8.3m passengers in 2007 (including its subsidiaries), representing a 14.6% rise, and believes this will be achieved through better fleet utilisation, higher frequencies and better connection with SkyTeam partners. Overall capacity will rise by 11% this year, although this varies greatly by segment, and particularly internationally. There are capacity growth targets of 19.5% on routes to CIS destinations, 16% on European routes and 8.2% to Asian destinations excluding Japan. Traffic to North America (Aeroflot operates 15 flights a week to four US destinations — New York, Los Angeles, Seattle and Washington DC), the Middle East and Japan is forecast to rise by less than 2% this year.

European capacity will increase despite the refusal of the Russian aviation authorities last year to allow Aeroflot to extend its operations in St Petersburg from the current domestic network to up to 30 European destinations. Instead the authorities reserved a European route monopoly at the airport for the airline created by the merger of St, Petersburg–based Rossiya Airlines and Pulkovo Airlines in October 2006 (now operating under the name Rossiya, and owned 100% by the government).

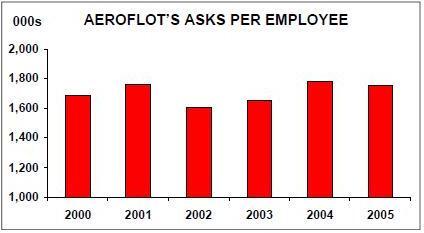

Nevertheless, Aeroflot’s domestic expansion in the rest of Russia will mean a further increase in staff numbers. At the end of 2005 the Aeroflot group (including regional subsidiaries) employed around 18,500 staff, of which 17,064 were in airline operations. Though Aeroflot has a relatively bloated employee base that makes productivity poor (see graph, page 14), staff costs are relatively low in Russia compared with western Europe, and employees accounted for 14.9% of costs in 2005 — a percentage considerably lower that at any of its major European rivals.

Aeroflot has, of course, been trying to reduce costs for several years, but the prime motivation for this has been fuel prices, which doubled in Russia over the 2003 to 2005 period. Fuel costs of $741m in 2005 were 49% up on 2004 and accounted for 32.3% of total costs (25.3% in 2004). As a reaction to the rising fuel bill, Aeroflot increased fares by around 15% in 2005, and while international passengers carried remained flat, domestic passengers carried rose by 17.6% in 2005. But Aeroflot hedged only 6% of its fuel needs in 2005, and though fuel costs rose by "just" 26.3% in the first nine months of 2006, to $691.1m, the airline says it is now considering hedging up to 30% of its fuel needs every year. And although the current reduction in fuel prices comes as a relief to Aeroflot, the fact that Russian aircraft are much less fuel efficient than western aircraft has led to an overhaul of the entire fleet. And as a higher proportion of the fleet will be owned going forward, this will also lead to a reduction in aircraft leasing costs (which totalled approximately $180m in 2006).

Other cost–saving initiatives include the construction of a new $100m headquarters for Aeroflot in Moscow (not far from Sheremetyevo), which will be completed in 2010. Once finished, this will save the airline the $10m a year that it currently pays for renting various offices throughout Moscow.

Good prospects?

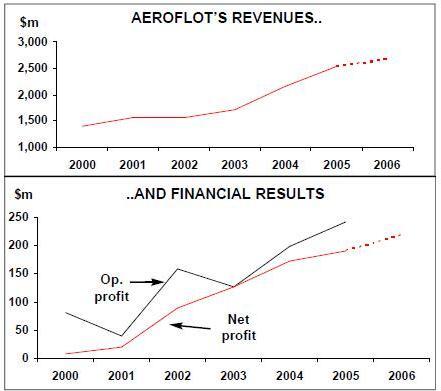

Aeroflot is also tackling distribution costs through a encouraging a higher proportion of telephone and online bookings; the airline is still too dependent on selling tickets via the Russian travel agent network, which accounted for 30% of all sales in 2005. Results for full 2006 are likely to be encouraging. In the first nine months of 2006 net profits rose 46.2% to $186.3m (under IFRS standards), with operating profit rising 36.8% to $246m and revenue up 15.7% to $2.1bn. Full year results are expected to come in at $2.66n in revenue, with net profits reaching $218m, more than 14% up on the 2005 figure (see graphs, page 15).

In 2007 Aeroflot’s revenue is forecast to grow by 21%, although net profit will remain just above the $200m level, according to Aeroflot CEO Valery Okulov. The latter is due primarily to the need to devote increasing amount of capex to upgrading Russian equipment (which in 2006 included installation of wing enhancements and lighter internal fittings on Tu154s in order to reduce fuel consumption); to the requirement to invest in domestic expansion eastwards; and to the fact that the change to IFRS from Russian accounting standards will reduce net profit by an estimated $100m in 2007, according to Aeroflot.

The good news is that Aeroflot is relatively strong financially. Its debts have been cut substantially, and as at the end of September 2006 Aeroflot’s long–term debt was just $106m, while cash and cash equivalents stood at $63m.

Crucially, this year Aeroflot is being boost–ed by two key strategic developments. 2007 will be the first full year in which Aeroflot reaps the benefits of being in the SkyTeam global alliance (which it joined in April 2006). Aeroflot already code–shares with Delta and has asked for permission to code–share with fellow SkyTeam members Continental and Northwest. Aeroflot estimates the revenue impact of joining SkyTeam at around $20m a year, but perhaps the more valuable benefit is the raising of some of Aeroflot’s operational and commercial practices to the standards requited by SkyTeam. This has included a new reservations system (supplied by Sabre), a proper internet booking facility and the installation of self–service check–in kiosks at Sheremetyevo — all standard practice at international airlines, but not at Aeroflot prior to 2006. The new infrastructure boosted revenues by around $15m in 2006, Aeroflot believes, although the capital cost of the upgrades is considerable.

The second key development is the imminent provision of an efficient, modern hub in Russia (which Aeroflot has never had), when a long–awaited new Terminal Three opens at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport, the airline’s base, at the end of the year. Sheremetyevo has experienced severe overcrowding for several years, but Aeroflot and its partners will transfer all their flights at the airport into the new $430m terminal, which will have a capacity of 10m passengers a year. The terminal will enable easy transfer between domestic and international SkyTeam flights, and also allows Aeroflot to connect passengers arriving on European flights through to connections into Asia and east Russia, with Okulov talking of developing a "bridge between Europe and Asia".

The terminal will boost Aeroflot’s profit line by around $20m per year, it is estimated, and Aeroflot is financing the project by selling 45% of the development to two state–owned Russian banks in exchange for $130m in cash as well as a 13–year, $475m loan. In the first part of that deal Vnesheconombank (VEB) bought 20% of the terminal in January, while Vneshtorgbank (VTB) will buy another 25% later this year. After these deals the "net" cost to Aeroflot of the terminal is believed to be around $150m. It’s also possible that Sheremetyevo airport itself may buy another 25% of Aeroflot’s share.

The bad news is that at some point over the next few years Aeroflot is going to take a huge hit on its bottom line from the loss of a peculiar hangover from the Soviet era — fees paid by international airlines overflying Siberia. These are collected on the government’s behalf by Aeroflot, but the airline retains a staggering 70% of the fees for doing so. It’s difficult to calculate the precise amount that this benefits Aeroflot, as the airline does not separate out the overflight revenue/ profit. In Aeroflot’s 2005 accounts, within "other revenue" there is an "airline revenue agreements" category, which includes overflight revenue as well as revenue from code–sharing and pooling; this totalled $357m in 2005. One analyst estimates that overflights were worth $277m in 2004 alone (representing 13% of total revenue in that year). This goes straight to the profit line, with the only deduction being tax. To be fair, other analysts say the figure is lower, at around $100m- $150m per year, although this is still a substantial sum. Following talks with the European Commission, Russia has agreed to abolish these charges by 2012, but the Commission is now putting pressure on Russia to speed up the timetable for abolition, and pressure will intensify once Russia joins the WTO.

Domestic chaos

A slightly more intangible challenge for Aeroflot is improving passenger service over the next couple of years, although in–flight catering and entertainment has improved substantially recently. However, Aeroflot has to balance improved services with the need to cut costs — last year the airline introduced a paid–for service for alcoholic drinks in economy class as part of the drive to compensate for higher fuel prices. Aeroflot is facing the same problems as the rest of the Russian aviation sector — increasing penetration by foreign carriers combined with rising fuel prices and an over reliance on ageing, fuel–inefficient Russian aircraft.

In 2005 (the latest year for which data is available) foreign airlines accounted for just over 31% (7.3m passengers) of the international market to/from Russia, with Aeroflot carrying 21% and five other airlines/groups (Vim–Avia group, Sibir, Pulkovo, AirUnion group and TransAero) accounting for 32%. The domestic market is more fragmented, with Aeroflot, Sibir, the AirUnion group (KrasAir, Domodedovo Airlines, OmskAvia, Samara and SibAviaTrans), UTair and Pulkovo accounting for 57% of domestic passengers — although the rest is divided between more than 150 much smaller small airlines.

So far foreign LCCs have not had a major impact in the Russian market. Air Berlin and germanwings operate a handful of routes, but as yet neither easyJet nor Ryanair fly to Russia — although easyJet is believed to be looking at the potential for the market. However, in January the first Russian–based LCC was launched — SkyExpress, which operates a couple of 737s on routes from Moscow’s Vnukovo airport to Sochi (a leisure destination), Rostov–on–Don (home of Aeroflot–Don) and Murmansk. The airline was launched by the owners of KrasAir, two Russian investments funds and a number of private investors, although the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development bought a 20% stake in December 2006 for an investment in the region of $10m-$20m.

SkyExpress tickets are sold online and, most importantly, via the network of 40,000 post offices in Russia, as well as a mobile phone retailer. Flights are being offered for as little as $19 and the airline hopes to tap into the large proportion of the population that cannot currently afford to fly (the average salary in Russia is $4,800 per annum). Ironically, despite the plethora of airlines after the break up of Aeroflot, the number of domestic passengers has fallen from 130m to less than 20m a year in the last 15 years, thanks largely to the increase in fares.

SkyExpress will add another six leased 737s through the year, with a planned network of eight domestic routes by the summer and a target of 1.2m passengers carried in 2007. The longer–term target is to build a fleet of 44 aircraft, and if these plans come into fruition this will be a major challenge to Aeroflot, not least because it will encourage other LCCs in the domestic market.

However, the challenge that Aeroflot faces from foreign and domestic competitors are being exacerbated by the chaotic state of the Russian aviation sector, which — while not as bad as in the immediate period after the break–up of the USSR in the 1990s — is still in a state of flux. The core problem is that the industry is still fragmented, even though over the 2000s the number of Russian airlines has halved, from around 400 to less than 200. That’s still way too many, even for a country as huge as Russia, particularly as the vast the majority of these operate a handful of obsolete aircraft and — crucially — cannot afford to upgrade to western aircraft.

These so–called "babyflots" continue to survive only because they were handed aircraft and other assets for free in the 1990s, but as Oleg Sudakov, analyst with Rye, Man & Gor Securities in Moscow, says, "these smaller airlines will go out of business when their aircraft are fully depreciated, or else they will be acquired by larger companies".

The problem is, this consolidation is happening at a sluggish pace, and so the Russian government — mindful of the concern about the growing presence of foreign airlines in the country — is now frantically trying to reduce the sector into to a handful of carriers that are more robust financially, which can replace ageing aircraft with modern western equipment and that are strong enough to establish hubs throughout Russia (and so lessen the dependence of the aviation industry on Moscow).

It’s difficult to keep count, but at present the Russian government completely owns more than 55 airlines and holds stakes in around 60 others, and — unsurprisingly perhaps — within parts of the government there has been a growing lobby to re–consolidate the aviation industry around Aeroflot. Many regional governments in Russian also see Aeroflot as a white knight that can rescue debt–burdened and/or loss making local airlines. In 2006 the state property fund therefore proposed consolidating up to 100 state–controlled regional airlines back into Aeroflot, the effect of which would be to increase the government stake in Aeroflot to more than 75%. Some managers within Aeroflot are believed to favour this option, but most others, including CEO Valery Okulov, as well as important allies in the government, are fiercely opposed, and prefer Aeroflot to cherry pick the best regional airlines as needed.

The latter alliance of interests appears to have won the argument, and Aeroflot is likely to be helped in its more "selective" regional acquisition policy by the transfer of its former CFO, Yevgeny Bachurin, to the Russian civil aviation authority in May last year, where he is now responsible for the re–consolidation of the Russian airline industry. Last year Aeroflot therefore proposed taking over six airlines based in the east of Russia — Pulkovo (in which the state owns 100%), GTK Rossiya (100%), Dalavia (100%), Vladivostok Avia (51%), KrasAir (51%) and Sibir Airlines (25%). Combined with existing Aeroflot subsidiaries, this would result in a domestic market share of more than 50% for the group, and an international share of approximately 60%.

However, many of the airlines named by Aeroflot insisted they wanted to have a say in the process of consolidation, and some were fiercely opposed, particularly KrasAir, which heads up the AirUnion alliance of five Russian airlines. KrasAir is based in Krasnoyarsk and operates a mixed fleet of 40 aircraft, and instead proposed that the members of the AirUnion merge to form a decent sized competitor to Aeroflot. It’s also uncertain as to whether Rossiya (into which Pulkovo was merged late last year) wants to be part of Aeroflot, while Vladivostok will definitely not be part of Aeroflot’s plans due to (depending on the source) either a willingness of the government to maintain competition in the region, a reluctance of Aeroflot to become involved with the airline, or a wish of the airline itself to remain independent. Sibir — which rebranded as S7 Airlines last year — is now due to be auctioned off by the Russian government early in 2007.

However, one of the airlines among those "chosen" by Aeroflot was receptive to the idea, and so in early 2007 the Aeroflot board gave formal approval for "Aeroflot–East" to launch via the takeover of Dalavia and another airline, Sakhalin Aviatrassy (SAT), which will be combined with Aeroflot’s existing operations in the region. Dalavia is based in Khabarovsk and operates 25 Russian aircraft to around 30 destinations, with international routes to Japan, China and South Korea. It carried 0.58m passengers in 2006. SAT carried 0.12m passengers in 2006 and operates 10 aircraft out of the island of Sakhalin on 14 mostly domestic routes, although there are services to Japan, China and South Korea.

Aeroflot-Eastwill be based at Khabarovsk (30km from the Chinese border), where a hub operation is to be built up, although Aeroflot says it will take two years to bring the acquired airlines up to "Aeroflot standards". It’s probable that other airlines will be rolled into Aeroflot–East at a later stage, and among the possibilities is Yamal Airlines, based in Siberia with a fleet of 22 Russian aircraft. Potentially also part of the new regional grouping will be former employees and aircraft of Mavial Magaden Airlines, a Siberian–based airline that operated six aircraft to local destinations as well as Moscow, St Petersburg and Alaska, but which suspended operations last year (leading to a hunger strike by employees in an attempt to get their outstanding wages paid).

Whichever regional airlines do become part of Aeroflot’s eastern empire, the most likely mechanism will be that airlines are acquired in exchange for newly–issued shares in Aeroflot being given to the government, who will subsequently sell them in the open market, thus improving Aeroflot’s liquidity.

Once established, Aeroflot–East will join the two existing major subsidiaries — Aeroflot- Don and Aeroflot–Nord.

Aeroflot Don is based in Rostov–on–Don in the south of Russia, and operates a fleet of 13 aircraft — all but two of which are Tu–134s or Tu–154s — on 17 domestic and regional routes, with the most important routes including Rostov to Moscow and St. Petersburg and handful of international destinations, including Frankfurt, Tel Aviv, Istanbul and Dubai. The airline carried 0.59m passengers in 2006 (1.9% down on 2005), but the first western aircraft — a pair of 737–500s on six–year operating leases from Pegasus — arrived in August last year, and another four will be added to the fleet during 2007 as it seeks to introduce more modern equipment to its key domestic and European routes. Aeroflot–Don had previously planned to introduce Fokker 100s into its fleet, but faced regulatory problems due to non–certification of the Fokker 100 in Russia, with the relevant authority (the Interstate Aviation Committee) reluctant to grant certification to a model that is no longer in production.

The airline dates back to the 1920s, and was previously known as Donavia Airlines until Aeroflot acquired a 51% stake 2000, after which it became Aeroflot–Don. The rest of the shares were held by Opt Invest, a Russian investment company, but at the start of 2007 Aeroflot bought all of the shares in a deal in which few details have been revealed.

Aeroflot-Nord carried 0.8m passengers in 2005 and is based at Arkhangelsk Airport in the north of the country, It was launched in 1961 as Arkhangelsk Airlines, before Aeroflot acquired a 51% stake in 2004 (with the rest being held by Aviainvest, although again Aeroflot plans to acquire a 100% stake as soon as possible). The airline operates a fleet of 25 aircraft (with the only non–Russian types being four leased 737–500s, introduced last year) on more than 30 domestic and international routes, including services to Norway, Sweden and Finland. The 737s had initially been considered an a temporary measure, with the airline’s management reportedly favouring an order for new An–148s, but the influence of its parent is likely to result in further 737 leases.

Elsewhere, Aeroflot pulled out of a deal to buy a majority stake in Moscow–based charter airline Continental Airways in 2005 after concern about tax reimbursements owed to the airline by the Russian government, as well as about ambiguity over who the actual owner of some of the Continental shares was. Instead, in 2006 Aeroflot set up Aeroflot Plus, its own VIP charter operation that uses the last IL–86s in the Aeroflot fleet and three older Tu–154s. In contrast to elsewhere in Europe, the Russian charter sector has been growing strongly in the last couple of years, based on increasing traffic flows to popular Russian holiday destinations.

Fleet farce

Another carrier being linked with Aeroflot is Ural Airlines, a 26–aircraft carrier with a network that overlaps considerably with Aeroflot’s regional routes, but which is attractive to Aeroflot as the airline’s management owns 73% of its shares, with just 27% held by the state. In the late 1990s Aeroflot operated 120 aircraft — of which just 20 or so were western types (Aeroflot aircraft went through spate of accidents in the early 1990s) — with the fleet consisting of 12 different types. This variety of types and the large amount of unreliable and fuel–hungry Russian models was simply not viable for Aeroflot in the long–term. As fuel prices have risen through the 2000s so Aeroflot has tried to rationalise the fleet, but pressure to increase the pace of modernisation has also come from the SkyTeam alliance. The goal is to reduce aircraft types to four, but although the situation has improved, Aeroflot is still some way off achieving that.

With one major exception (see below), Aeroflot’s fleet will be based on western aircraft from now on. New Russian aircraft development has been beset by many problems, not least of which has been an inability to define an accurate price per unit in advance. Although the Russian government recently decided to consolidate the remaining civilian (Ilyushin and Tupolev) and military (Sukhoi, MiG, Yak and Irkut) aircraft producers into one company — the United Aircraft Building Corporation — with the civilian aircraft makers under the control of the Russian defence minister Sergei Ivanov, it is too late to make existing models competitive with Airbus or Boeing.

Today Aeroflot’s mainline fleet comprises 91 aircraft (see table, opposite), of which 40 are western models. On medium haul, Aeroflot’s 25–strong fleet of Tu–154s will gradually be phased out by the end of 2010, with its replacement being the A320 family, of which the airline currently has 25 aircraft. Five A320s and A321s are on outstanding order, most of which are arriving on 12–year finance leases over the next year, but by 2010 Aeroflot will place an order for 45 A320s, according to Valery Okulov, which would be worth around €2.4bn at today’s list prices.

On short–haul Aeroflot operates a fleet of 13 Tu–134s, a model that Aeroflot admits is both old–fashioned and uneconomical. The 76–seat Tu–134s are being phased out this year, either being sold or passed on to its regional or charter subsidiaries, and they will be replaced ultimately by 30 Sukhoi Russian Regional Jets (RRJs), for delivery in 2008 onward (with 20 more on option).

However, the order process for the RRJs went on for more than a year, largely due to the fact that as the Russian government owns a majority stake in both Aeroflot and Sukhoi, this triggered the necessity for a long–winded "related party" approval procedure. Whether the 95–seat RRJ has been purchased purely from a commercial viewpoint is doubtful. The Russian government is believed to have put pressure on Aeroflot to become the launch airline for the new model, and the order has been approved despite reported reservations by some airline executives on everything from the model’s technical specifications and price to the feasibility of the delivery timetable. There was also a preference among some Aeroflot managers for the An–148 aircraft instead, complicated by the fact that the National Reserve Corporation (known as NRC, and a 30% shareholder in Aeroflot) has an interest in Antonov, but that deal didn’t happen after concerns that the unit price of the An–148 was too high.

Whatever the decision–making process, the RRJ order is worth around $630m (approximately 15%-20% less than list prices), and the aircraft will arrive on a mix of finance and operating leases. To fill the gap between the last of the Tu–134s and the arrival of the RRJs, some 737s will be leased on a short–term basis.

It’s on long–haul, however, that Aeroflot has managed to make itself look something close to incompetent, via a long–running saga over a new order that has still not been resolved. Aeroflot completed an evaluation of its long–haul fleet options back in 2005, identifying a need for up to 22 aircraft for delivery in 2009–2015. The A350 and the 787 were (and are) the favoured types for the order, but the decision has been complicated by the fact that Russian airlines have to pay a 20% import duty as well as 18% VAT on all imported aircraft. Previously Aeroflot has negotiated exemptions with the government on these import taxes and tariffs, usually by promising to buy a certain number of Russian–built aircraft at the same time, but this time around the government insists that it can no longer make an exception for Aeroflot (even though the airline is committed to buying six IL–96–300s). That’s partly a negotiating tactic in order to pressure the airline into buying further Russian types, but a looming external factor in the situation has been talks over Russia’s imminent entry to the WTO, in which aircraft import tariffs are a key discussion point. (since when Russia joins the WTO, taxes on western aircraft will have to be reduced substantially).

So while in early 2006 Aeroflot provisionally chose the 787 as its preferred model, a firm decision was delayed time and time again as Aeroflot negotiated with the government over a tariff exemption, and the government negotiated with the EU and the US over entry into the WTO. In April, Aeroflot was then "persuaded" to switch its preference over to the A350, a move that some analysts saw as a non–too–subtle Russian government response to perceived aggressive pressure exerted by the US over the terms of Russia’s entry to the WTO.

But — as the year progressed — a firm order was still not forthcoming. Aeroflot’s managers used the delay to make it clear that they preferred the 787 (and specifically the 787–8 and 787–9 stretch version), largely because it would be available earlier than the A350 (2010 rather than 2012). Yet another complicating factor became the Russian government’s keenness to increase its influence in Airbus after Vneshtorgbank (VTB), a state bank, acquired 5% of EADS in the summer of 2006 for $1bn, and drew the Airbus group into supporting the struggling Russian aerospace industry.

A final decision between Airbus and Boeing was going to be made at Aeroflot’s board meeting in September last year, but in the end the board decided not to make a firm order after the Russian government failed to make clear which manufacturer it wanted the airline to choose. Bizarrely, a few days later the privately–held NRC signed a preliminary agreement with Boeing to purchase 22 787s at prices fixed as of 18 months previously (roughly equivalent to a discount of $15m- $20m per aircraft on current list prices, and thus making the whole order worth around $3bn). In signing the deal, NRC paid Boeing around $40m to secure a month’s option on production slots for the 787 in 2010 onwards, in the clear expectation that final approval from the board the government was just a matter of days away.

Inevitably perhaps, Aeroflot missed the November 1 deadline to confirm the NRC "order", and so Boeing awarded the production slots for the 22 aircraft to other customers. NRC was furious about the delay and persuaded Boeing to backtrack and extend the deadline to December 1, but — to no–one’s surprise — Aeroflot/the government still could not make a confirmation by that date, and so the delivery slots were lost for good.

One senior Aeroflot executive describes the situation as "farcical", while another says the airline is "hamstrung" by the situation. The owner of NRC — Alexander Lebedev — a billionaire businessman who is a deputy of the Duma and a former KGB employee, didn’t hold back in his reaction, saying that: "The bureaucracy of the government is very inept. The state has practically left the national airline with no modern long–haul planes, and losses from that decision will run into hundreds of millions of dollars." The NRC is threatening to sue the Russian government over its "dithering" in choosing between Airbus and Boeing, but that will not help the airline solve its fleet problem.

Further developments in the saga appear to occur every week, but the latest news is that Aeroflot has "changed" its analysis of its long–haul needs, and now needs a fleet of up to 45 long–haul aircraft, with differing capacities. This should have allowed the compromise of splitting requirements between Airbus and Boeing — even though that will not be optimal from an operating viewpoint — with orders for 22 A350XWBs worth $3bn, as well as 22 787s. The likelihood of this, however, depended on whom you spoke to, and other sources within Aeroflot indicated another, final twist in the story, with the growing coolness between the US and Russian governments potentially leading to a placement of the total (expanded) long–haul requirement with Airbus. If this occurs it will likely set off a storm of complaints from both Boeing and the US government, but as Aviation Strategy went to press, Aeroflot said it had indeed signed an MoU to buy 22 A350s, as well as a deal to lease up to 10 A330–200s, the latter of which will cover the minimum seven–year period until the A350s arrive.

If this deal is confirmed, the unavailability of the A350 XWB until 2014 at the earliest (and even this is subject to confirmation of the A350 production schedule) means that Aeroflot still has to find interim (and costly) solutions to its long–haul fleet needs — over and above the leased A330s. That has already resulted in extending leases on the eleven 767–300s Aeroflot currently operates, and extending the life of its six owned IL–96- 300s, even though the model has relatively high operating costs. Aeroflot also has another six IL–96–300s on order, which will come on 15–year leases from the manufacturer — even though back in 2005 there were concerns from the Russian authorities over technical reliability of the model, particularly on the braking system. Those concerns led to a grounding of the existing IL–96s in Aeroflot’s fleet in August that year (for 43 days), which took out just under half of the airline’s longhaul capacity at the time and cost the airline a great deal of money. Hopefully the longhaul crisis will not persuade Aeroflot to hang on to its remaining IL–86s, which were supposed to be taken out of the fleet in November last year, although Aeroflot has apparently struggled to find suitable buyers or lessees.

A bright future?

On cargo, last December Aeroflot separated out its operations (it is currently the largest cargo operator in Russia) into a separate subsidiary called Aeroflot Cargo, though still fully owned by the mainline. Aeroflot currently operates four DC–10–40Fs from its cargo hub at Frankfurt Hahn, but they should be replaced on international routes by up to six MD–11Fs leased from Boeing Capital Corporation, and scheduled to be delivered this year and in 2008 (although they were originally supposed to be delivered from 2006 onwards, and there is no confirmation of this order yet). The DCs would then be reassigned to purely domestic Russian routes. Longer term, the cargo unit will look to order new aircraft, most likely to be 777s. Cargo generates around 10% of Aeroflot’s revenues, and the group is looking to increase cargo volumes by 9% in 2007. It’s clear that Aeroflot is facing severe challenges at the moment, many of which stem from the government’s inability to make sensible, timely decisions, whether on which aircraft to buy for Aeroflot or on the way forward to clear up the mess in the Russian aviation industry in general.

From Aeroflot’s point of view it mattered relatively little which manufacturer the government chose for long–haul aircraft — just as long as the government did make a choice and that the airline received new western aircraft as soon as possible. But the chance of receiving new aircraft in the next few years has gone, and the cost to Aeroflot will run into tens of millions of dollars, if not hundreds of millions.

As for restructuring the Russian aviation industry, it’s vital that the government does not bend to pressure to force regional airlines upon Aeroflot. There’s no doubt that many of the smaller regional airlines will be loss–making for ever, and should either be allowed to go bankrupt or (more likely) receive continuing state help in order to survive,. This may necessitate wrapping up these airlines into a new state aviation concern — but one completely separate to Aeroflot.

On the positive side, the management team at Aeroflot is much improved (in November last year the airline successfully sued three former senior executives — including Nikolai Glushkov, a former deputy director — for embezzling millions of dollars from the company in the late 1990s). With (at some point) a new fleet, a continuing strategy of picking off the strongest regional airlines in order to secure feed, and the benefits of both SkyTeam and the new terminal at Sheremetyevo, Aeroflot can have a successful future, but it’s vital that the state divests its remaining stake as a matter of urgency. Currently, the Russian government owns 51.2% of Aeroflot, with employees having 14% and NRC 30%, with a negligible free float of around 3%.

Although an ambitious (and unrealistic) plan by the state to privatise the airline by 2005 inevitably came to nothing, Russian government sources say that it wants to dispose of its stake in Aeroflot at some point, but there are no plans as yet for an IPO, either in the short- or long–term, (and anyway, this can’t happen until Aeroflot is formally struck off the list of Russian "strategic enterprises" by the Russian president). Until that situation changes (and NRC is believed to be lobbying hard for an IPO), analysts will be sceptical about the long–term future of Russia’s flag carrier.

| Fleet | Orders | Options | |

| Aeroflot Russian Airlines | |||

| A319 | 8 | ||

| A320 | 10 | 2 | |

| A321 | 7 | 3 | |

| 767-300 | 11 | ||

| DC-10-40F | 4 | ||

| IL-86 | 7 | ||

| IL-96 | 6 | 6 | |

| Tu-134 | 13 | ||

| Tu-154 | 25 | ||

| Sukhoi SuperJet-100 | 0 | 30 | 20 |

| Total | 91 | 41 | 20 |

| Aeroflot-Nord | |||

| 737-500 | 4 | ||

| An-24/26 | 7 | ||

| Tu-134 | 10 | ||

| Tu-154 | 4 | ||

| Total | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Aeroflot-Don | |||

| 737-500 | 2 | ||

| Tu-134 | 2 | ||

| Tu-154 | 9 | ||

| Total | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Aeroflot total | 129 | 41 | 20 |