Delta Airlines: Deleveraging and de-risking

October 2011

Delta, the second largest US carrier, is well positioned to weather a potentially tougher economic environment because of its successful 2008 merger with Northwest, its continued capacity and capex discipline and progress in de–leveraging the balance sheet. Will it also manage to keep unit operating costs in check?

Delta is fortunate in that, with the merger integration behind it, it is enjoying a period of relative calm. Unlike the other two of the “US Big Three”, it has no major dramas or risks to deal with. American faces serious challenges and in recent weeks has been subject to speculation that it is now headed for Chapter 11 – something that is not likely in the near term because of its strong cash reserves, and because its goal is to avoid bankruptcy (see Aviation Strategy, May and July/August 2011, for analysis of AMR’s problems).

United Continental, in turn, is performing well financially but still has ahead of it the toughest and riskiest aspects of the merger execution: labour and systems integration (see Aviation Strategy May 2011).

This period of relative calm has enabled Delta’s management to focus on managing the airline to the best of their abilities. The results are impressive.

First of all, Delta is earning solid profits and generating significant free cash flow. Its revenue generation has been so strong that it has more than offset a $3bn higher fuel price impact this year.

Second, Delta is showing remarkable capacity discipline. Its system ASMs will decline by 4–5% in the fourth quarter, with a further 2–3% reduction already pencilled in for 2012.

Third, as part of efforts to “recalibrate the business to high fuel prices”, Delta is seeking to bring its non–fuel unit costs back to the 2009/2010 levels.

Fourth, Delta is exhibiting remarkable capital spending restraint, despite having a relatively old fleet and a much smaller orderbook than its peers.

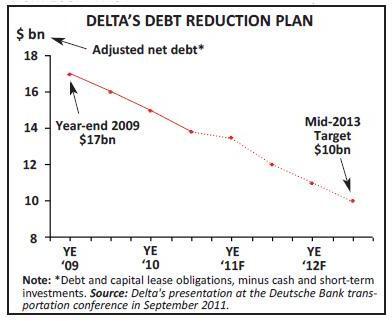

Fifth, Delta is determined to de–leverage its balance sheet. It is already at the halfway mark in reducing adjusted net debt from $17bn at year–end 2009 to $10bn by mid–2013.

Sixth, thanks to its conservative spending and balance sheet management policies, in the future Delta may be the first of the top three carriers to achieve its financial targets – a 10–12% annual operating margin, $5bn EBITDAR and a sustainable 10%-plus return on invested capital (ROIC). Of course, despite the capacity cuts and fiscal austerity, Delta also has many exciting product, network and alliance developments in the works. Among other things, it is expanding in Asia and Latin America, strengthening its position in the New York market, acquiring a stake in Aeromexico as part of a deeper commercial alliance — which also offers intriguing longer–term potential for Delta to grow its MRO business and reduce costs – and implementing an immunised code–share relationship with Virgin Australia on the Pacific.

Virgin Atlantic may make its global alliance decision this autumn. Although Star would seem to have the edge (in light of Virgin’s interest in Lufthansa–owned bmi), SkyTeam and the Delta/Air France- KLM/Alitalia transatlantic JV have undoubtedly presented an offer package worth considering.

Delta’s main challenge is that cost pressures will rise as capacity shrinks, making it harder to reach cost cutting targets and maintain unit costs that are among the lowest in the legacy sector.

Southwest’s aggressive growth in Atlanta following its acquisition of AirTran is another negative, though the impact on Delta may not be material. First, Southwest merely replaced an existing low–fare airline. Second, it is probably a more rational competitor than AirTran (because it has higher costs and is more profit–oriented). Third,the new routes that Southwest is likely to introduce to Atlanta represent perhaps less than 1% of Delta’s system revenue.

Outperforming its peers

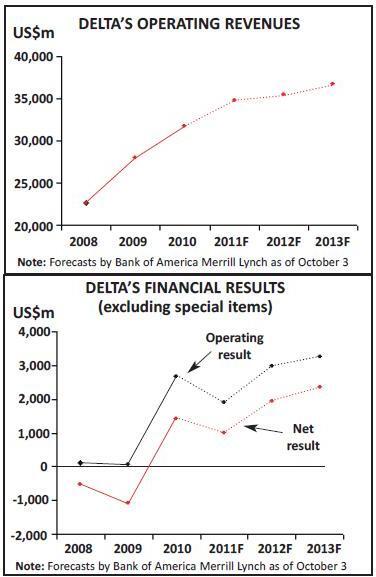

Because Delta and Northwest were the last legacy carriers to restructure in Chapter 11 (both emerged in the spring of 2007), the airline that resulted from the October 2008 merger enjoyed a cost advantage over its peers. In 2010 Delta finally showed concrete benefits from the merger, achieving operating and net profits of $2.7bn and $1.4bn, respectively, though UAL still beat it in the margin league. Delta generated a respectable 8.4% operating margin and a 10% ROIC.

This year Delta has continued to post solid results. In the June quarter, it grew its revenues by 12% and earned a $636m operating profit (7% margin), despite $1bn higher fuel expenses and $125m negative impact from the Japan crisis (Delta has the highest Japan exposure among the US carriers).

In the September quarter Delta grew revenues by 10% and posted a $1bn operating profit before special items and profit–sharing.

The 10.5% operating margin was expected to be among the highest earned by the large legacies.

In the past six months Delta has been outperforming its peers in terms of unit revenue growth, partly because of its strong corporate contract gains. Bank of America Merrill Lynch estimated last month that the airline’s PRASM gains exceeded the sector average by two points in the September quarter and that the lead will widen to four points in the current quarter.

Although the full–year 2011 margin is expected to dip to the mid–single digits because of fuel, at this point analysts are predicting 8–10% operating margins in 2012 and 2013.

Capacity and cost discipline

Delta’s impressive capacity restraint and cost cutting efforts reflect a determination to fully adjust the business model for a high fuel cost environment. Since the spring the airline has led the industry in reducing capacity for this winter. Delta’s system ASMs are falling by 4–5% in the fourth quarter, with much of the reduction focusing on the transatlantic market (down 10–12%), where RASM performance was disappointing last winter.

In May Delta and its transatlantic JV partners made the unprecedented move of announcing a joint reduction in transatlantic capacity. The JV’s 4Q ASMs will now fall by 7–9%, compared to a 7–8% increase planned originally. Although Delta did add capacity rather liberally last winter, the JV’s actions are impressive given that the transatlantic is a fiercely competitive market where the three global alliances have similar market shares. (United announced in July that its transatlantic JV with Lufthansa and Air Canada had reduced 4Q growth from 6% to flat.) Delta’s actions have drawn much praise from analysts. JP Morgan’s Jamie Baker suggested in mid–September that “among industry management teams, only Delta is(thus far) taking the threat of weakening global economic trends seriously”. Baker commented that “having followed this sector for close to two decades, such proactivity is both unusual and refreshing”. (By comparison, United is cutting 4Q consolidated capacity by 3% and is currently targeting flat capacity in 2012. In early October American announced plans to accelerate 4Q mainline capacity cuts to 3% and to retire up to 11 757s in 2012.) Delta’s service reductions will be across all regions except Latin America. The airline is cutting frequencies or getting out of markets where revenue has not kept pace with higher fuel costs. Domestically, Memphis will bear the brunt of the cuts; the small ex- Northwest hub will see a 25% reduction in daily departures, starting in January.

Delta is also making an effort to better match flying to seasonal demand in order to reduce or eliminate seasonal losses. This winter it will fly 20% fewer seats than in the summer – a greater differential than it has ever had historically.

The 4Q capacity cuts are helping Delta maintain relatively strong (10%) RASM performance into the fourth quarter, which otherwise might see deceleration of the positive trend due to growing economic uncertainty.

Delta is determined to remove the costs associated with the “resizing” by trimming its fleet, workforce and facilities. Furthermore, Delta wants to bring its non fuel CASM back to the 2009/2010 level of 8.25–8.30 cents per ASM (its unit costs have been trending around 3% higher this year).

The fleet reductions include retiring 140 less efficient aircraft by the end of 2012 (half of them this year), including DC9–50s, Saab turboprops and more 50–seat RJs. It is hard to believe that Delta still had 32 DC9- 50s in its fleet at the end of June (average age 33.3 years).

This year’s retirements are projected to generate $250m of maintenance cost savings in the second half of 2011. Delta is also consolidating facilities and reducing its headcount by at least 2,000 through a voluntary exit programme this autumn. And efforts are being made to further reduce distribution costs by shifting more bookings to lower–cost channels. With the Delta–Northwest integration completed, there is also potential for further efficiency gains resulting from the merger.

However, analysts are sceptical that Delta can achieve the non–fuel CASM target in 2011 or 2012, which would involve reducing costs by $700–800m, given the magnitude of the capacity cuts. Delta’s management too have acknowledged that it could be a “multi–step process” of “gravitating towards the 8.25–8.35 cent range”.

On the positive side, Delta has a long history of keeping operating costs in check, its unit cost position remains competitive, and the fleet renewal will help.

Capex restraint and balance sheet de-leveraging

Recent months have seen a spate of large aircraft orders from global carriers (AMR, Air France–KLM, etc.) keen to get on with necessary fleet renewal, secure delivery positions and take advantage of the great deals that can be had as the Airbus- Boeing market share battles reach new heights (see Aviation Strategy’s analysis of the AMR orders in the July/August issue).

Delta, with its relatively old fleet, had been expected to be among those carriers. In early 2011 Delta’s top executives had stated that they would make a decision later in the year on replacing large parts of the airline’s short haul fleet and had asked manufacturers for proposals to deliver up to 200 narrowbody aircraft. Delta was believed to be in the market for large, medium and small single–aisle aircraft.

What materialised was an order for 100 737–900ERs in August, for delivery in 2013- 2018. And since then Delta has made it clear that there will not be a “part two”.

President Ed Bastian said at the Deutsche Bank conference in mid–September that the airline would not place more orders from any manufacturer for “the next couple of years”.

The 180–seat 737–900ERs will replace the airline’s older–technology 757s, 767s and A320s. But Delta has postponed the MD–80/90 replacement decision (for which Embraer and Bombardier are obviously strong contenders). Notably, at this stage Delta also opted not to include orders for the planned re–engined 737 MAX.

But Delta has continued to acquire used MD–90s. In the first half of 2011 it purchased seven and leased four, and as of June 30 it had firm commitments for another 14 and options for seven. The management has described the type as a “very cost–effective aircraft for fleet replacement”. The MD–80 is a highly flexible aircraft and its economics are apparently still good at $90 oil.

A year ago Delta deferred the 18 787–8 orders that Northwest brought to the union (the type’s original North American launch customer) to the 2020–2022 period. Instead, Delta opted to upgrade its existing widebody fleet with flat–bed seats and other enhancements.

All of this illustrates Delta’s absolute determination not to be distracted from its main goal – de–leveraging the balance sheet. The management says that the 737- 900ER order maintains financial and capacity discipline. The aircraft are purely for replacement, offer significant savings from increased fuel efficiency and lower maintenance costs and will be cash flow positive and earnings accretive from the first year of operation.

Delta will receive the first 12 737- 900ERs in the second half of 2013, followed by 19 aircraft each year from 2014 to 2017, and the remaining 12 in 2018. The deal includes 30 options, which replaced previously held 737–800 options. Delta has a preference for owning aircraft and has obtained committed long–term financing for a substantial portion of the purchase price. Separately, the airline ordered $2.2bn of CFM56–7BE engines to power the 737–900ERs.

The size and timing of the order will enable Delta to maintain its total capital expenditure at a modest $1.2–1.4bn annually in the next three years. Aircraft capex will be only $210m in 2012 and $540m in 2013, rising to $760–780m annually in the subsequent years – all a far cry from the $2.8bn annual average spending in aircraft by Delta and Northwest collectively in the decade preceding their merger.

Delta has staged its capital projects very carefully. In 2008–2010 the focus was on merger integration. Currently, in 2010- 2013, the airline is spending on fleet, product and facility improvements. From late 2013 the focus will shift to the domestic narrowbody replacement.

Delta is more than halfway through a $2bn, three–year investment to “enhance the customer experience as a means of generating a unit revenue premium to the industry”. This means adding flat–bed and “Economy Comfort” seats on international aircraft and more first class seats and WiFi on domestic aircraft, renovating and expanding airport facilities and acquiring slots at key locations (more on these projects in the section below).

With adjusted net debt at the $13.8bnmark in June, and with plans to use all of the projected $2bn–plus annual free cash flow to pay down debt, Delta is well on its way to achieving the $10bn net debt target by mid–2013. The impact will be to de–risk the business and reduce annual interest expenses by around $500m between 2009 and 2013.

Delta’s scheduled debt maturities over the next three years are “relatively heavy but manageable” (as Fitch put it). The airline has taken advantage of market opportunities to refinance debt. In April it obtained a new $2.6bn credit facility to refinance the Delta Chapter 11 exit facility from 2007. This included a $1.8bn revolver,which came in handy because Delta’s cash reserves have been a little on the light side compared to peers. Delta ended the September quarter with total unrestricted liquidity of $5.1bn

New revenue opportunities

As a result of its investment projects, Delta is projecting as much as $1bn of annual incremental revenues by 2013. Those revenues would come from premium up–sell programmes and higher business traffic volumes attracted by the product enhancements.

The products already implemented include “Economy Comfort”, a new section in the first few rows of the international economy cabin offering more legroom, more recline and early boarding (similar to the upgraded economy products available on JV partners Air France–KLM and Alitalia). Delta began offering it in June on all 175 international aircraft, and it has been so successful that the carrier is now introducing it also domestically. Domestic fleet enhancements have included increasing first class seating by 13% on some 350 aircraft, interior upgrades and WiFi; the latter is now being installed also on the 228- strong dual–class regional fleet.

Delta is in the middle of installing full flat–bed seats in the Business Elite cabins of its widebody international fleet. So far about one third of the 140–plus aircraft have been re–fitted (including all 777s and 767- 400s), and the process is due to be completed by the end of 2013.

Delta is also revamping its e–commerce platforms to facilitate more innovative products and enhancing the FFP to reward the best customers. Almost 40% of Delta’s North American bookings are now through its website, making delta.com an attractive platform for selling ancillary items.

Obtaining state–of–the–art facilities at Atlanta (Delta’s main hub) and New York (which the airline sees as one of its biggest opportunities, see Aviation Strategy, Jan/Feb 2010) are a key part of Delta’s efforts to enhance the customer experience and hence boost revenues.

Atlanta airport’s new $1.4bn international terminal is set to open in the spring of 2012. It will dramatically improve passenger convenience (among other things, bringing to an end a cumbersome baggage process now required of arriving international passengers).

A new concourse with 12 international gates will facilitate growth for Delta and other airlines.

After long been handicapped by its ageing JFK terminal (T3), which was built in 1960 and compares very unfavourably with the modern facilities of competitors, Delta will be able to move its international operations to a redeveloped and expanded T4 in the spring of 2013. This first phase of a five–year $1.4bn project will give Delta nine new international gates, a passenger connector between T4 and T2 (which Delta will retain for domestic operations) and expanded baggage claim and customs areas. The airline has described it as a “game–changing” project; the many benefits to customers will include faster transit times and one of the largest Sky Club lounges in the Delta system.

The project is on schedule; work began in December 2010, when Delta also issued $800m of special bonds and signed a 30- year agreement with the airport. The second phase of the project (by May 2015) will see demolition of T3 to make way for aircraft parking.

Delta’s ambitions to operate a true domestic hub at LGA have just taken a major leap forward with the DOT’s approval of the slot swap with US Airways on October 11 (more than two years after it was first proposed).

Under the deal, which the airlines revised in May, Delta will acquire 132 slot pairs at LGA, while US Airways will get 42 slot pairs at Reagan National, rights to operate additional daily flights to Sao Paulo from 2015 and $66.5m in cash. The deal includes divestiture of 16 slot pairs at LGA and eight slot pairs at National. The transaction, which the airlines hope to complete by December 1, will involve Delta taking over most of US Airways’ Terminal C at LGA, to create an expanded two–terminal facility at the airport, and spending $100m on renovations and upgrades over two years.

This deal will enable Delta to double its destinations from LGA, significantly strengthening its position in the New York market amid intensified competition (from United Continental, American, JetBlue, Southwest and others). Given that LGA is New York’s preferred airport for business travel, the positive implications for RASM are obvious.

According to Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Delta’s management sees $300–600m upside to annual New York revenues by closing its relative RASM gap with competitors.

Network and alliance opportunities

Despite the need to keep overall capacity in check, Delta has had growth opportunities this year. The most promising of those originally – Tokyo Haneda – has had a very difficult start, because US–originating travel to Japan has remained severely depressed following the March disasters. Delta has suspended its Detroit–Haneda route until April 2012 though continues to operate Los Angeles–Haneda (the other new route introduced in February), as well as services to Narita.

On the positive side, however, because Japan–originating demand has recovered much faster, Delta is now able to add a new seasonal Fukuoka–Honolulu route in December – its ninth resort market out of Japan and a handy use for some 767–300ERs pulled from other markets.

As a result of the BA/AMR alliance slot divestitures, Delta was able to start serving London Heathrow from Boston and Miami in March. The flights are operated as part of the transatlantic JV with AF–KLM and Alitalia.

Delta’s position is not strong at either Haneda or Heathrow. At Haneda, it does not have feed because it lacks an airline partner in Japan. At Heathrow, it is a relative newcomer (2008) and SkyTeam has only a 6% share of seats there (compared to oneworld’s 47% and Star’s 26%). However, Delta needs to have a presence in key business markets such as Haneda and Heathrow, and those destinations offer long–term potential.

The best immediate opportunities are in emerging markets. China has been a major focus of Delta’s expansion in recent years. In June the airline restarted Atlanta–Shanghai flights (a route that had been suspended since 2008) and in July it launched Detroit–Beijing.

The other growth market is Latin America. After launching Detroit–Sao Paulo in late 2010, this year Delta has been building frequencies on the Atlanta–Brasilia route and has begun code–sharing with Gol. Service expansion this winter will include upgrading Atlanta–Brasilia to a daily service and introducing a new Minneapolis–Costa Rica route.

Delta is an enthusiastic proponent of alliances, all the more so because of its capacity and fiscal discipline and hopes of achieving a decent ROIC. Spearheading its efforts in this area is the transatlantic JV, which was signed in May 2009 (after securing ATI a year earlier), has been aggressively developed and is probably the most deeply integrated of the JVs. The spring saw some nicely coordinated expansion between Florida and three major European cities.

This year Delta has begun code–sharing with some of the notable new SkyTeam members, including China Eastern. Also, after two years of regulatory delays, Delta will be finally able to implement its immunised transpacific JV with Virgin Australia in early November.

In August Delta forged a very interesting deeper “long–term exclusive commercial alliance” with its SkyTeam partner Aeromexico. It will involve Delta investing $65m for a 3.6% stake in Aeromexico and a seat on its board. The two airlines also plan to expand their MRO agreement by investing $40m to build a joint maintenance facility in Mexico – something that could offer significant cost savings to Delta.

Delta executives have since then commented that they see the Aeromexico relationship eventually developing into a JV with ATI, once an open skies regime is secured. They also suggested that it could be a template for other relationships “particularly in South America”. One potential candidate is obviously Gol, which signed an MRO agreement with Delta back in February. Another is Aerolineas Argentinas, which Delta has already secured as a code–share partner ahead of its SkyTeam membership next year.