Virgin's airlines: Wise and foolish

October 2005

After reporting record profits for 2004/05, Virgin Atlantic Airways plans to double in size over the next five years. Is this a positive move by the flagship of Sir Richard Branson’s empire, or recognition that — as its name suggests — the airline is dangerously exposed to a transatlantic market that sooner rather than later will face greater competition?

Based at both London Heathrow and Gatwick, the long–haul carrier that was launched with a single leased 747 by entrepreneur Richard Branson in 1984 today operates 26 routes in total. 10 to the US , four to Africa, five to Asia/Pacific and seven to the Caribbean. This makes it the second–largest operator of long–haul routes in the UK.

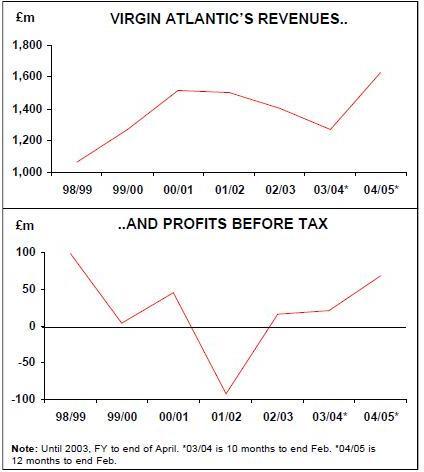

After September 11, Virgin Atlantic was affected severely by the collapse in business traffic across the Atlantic, and in the year to April 2002 the company made a loss before tax of £93m, even after cutting more than 1,300 staff. However, in 2002/3 Virgin Atlantic changed its strategy by starting to hire again and pushing ahead with business class innovation, in the expectation that it would be one of the first airlines to benefit when business travel levels returned to normal.

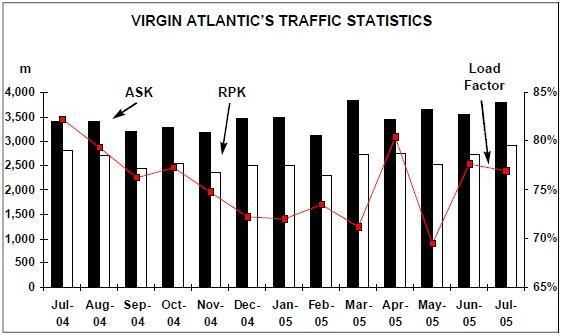

That proved to be an astute move, and the airline returned to profit in 2002/03. Profit rose again in 2003/04, and results for Virgin Atlantic’s 2004/05 financial year (the 12 months to the end of February 2005) seem even more impressive, with pre–tax profits of £68m — the best result since 1998/99 (see chart). This was based on turnover of £1.63bn, with 4.4m passengers flown in 2004/05. In comparison, in 2003/04 (a 10 month period only, due to a change in Virgin Atlantic’s financial year to match that of SIA, its minority shareholder) pre–tax profits were £20.9m on revenue of £1.27bn, with 3.4m passengers flown. Results were so good in 2004/05 that Virgin Atlantic’s employees received a profit–related bonus.

In business class, Virgin Atlantic carried 352,000 passengers in the 2004/05 year, a 26% rise on 2003/04. Business load factor was 56%, its highest percentage since 1999/2000. This was due partly to the 5% increase in capacity in the financial year, but more substantially to the revamped Upper Class Suite seat, which was launched in November 2003 (and which is still being fitted to the last of the airline’s A340–300s). Virgin Atlantic says the product is luring business passengers across from rivals such as British Airways, although BA is now revamping its own business class seat in response.

As the Virgin Group — which holds Branson’s 51% stake in Virgin Atlantic — is privately held, a detailed picture of the airline’s finances is impossible. But what is apparent is that the 2004/05 results were boosted by several extraordinary items, including £31m from the partial writing back of a provision for the value of Virgin Atlantic’s fleet following September 11. Virgin Atlantic also banked £16m from the sale of its 50% share in cargo handling company Plane Handling, which was a joint venture with Go–Ahead.

Without these two items, pre–tax profits would be £21m — which is almost the same as in 2003/04 — although that financial year only had 10 months. If the 2003/04 figure is extrapolated to 12 months, Virgin Atlantic’s 2004/05 profit before tax actually fell by more than 16%.

And the Virgin Atlantic financials also include tour operator Virgin Holidays, as well as cargo operations. In 2004/05 the tour operator contributed £407m of turnover, compared with £314m in the 10 months of FY 2003/04. That means the airline (and cargo) part of Virgin Atlantic recorded revenue of £1,223m in 2004/05, compared with £958m in the 10 months of 2003/04. If the 2003/04 figure is extrapolated to a 12 month basis, the airline’s 2004/05 revenue is just 6% higher.

The difference in profit margin between the tour operating and airline operation is unknown, but what is apparent is that Virgin Holidays is being given more prominence within the over–all Virgin Atlantic operation, for example by helping the airline choose which destinations to add to its network. As for Virgin Atlantic’s cargo business, it carried 149,000 tonnes in 2004/05, although that was just 4% higher than the 2000/01 financial year (the last financial year pre–September 11). 45% of cargo tonnage comes from routes to the US, while 44% is on flights to the Asia/Pacific region.

Expansion push

Branson intends to double both the revenue and fleet at Virgin Atlantic by the end of the decade, with the immediate aim for the 12 months to the end of February 2006 being a growth in capacity and revenue of between 10% and 15%.

More than 1,500 staff (including 150 pilots and 1,100 cabin crew) will be recruited by the end of 2006, although one–third of them will be for natural staff turnover. During the financial year to the end of February 2005 the Virgin Atlantic workforce increased by 600 (mostly cabin crew) to 8,118, and the extra 1,000 staff will lift the workforce to almost 9,500 by the end of next year. Longer–term, Virgin Atlantic is looking to increase its staff to 12,000 by 2010.

In terms of the fleet, Virgin Atlantic currently operates 18 A340s and 13 747s, at an average age of just under six years. Three A340–600s were received in 2004/05, and Virgin Atlantic currently has 21 aircraft on outstanding firm order. Two A340–600s are outstanding from a previous order, while 13 A340–600s were ordered in August 2004, for delivery in 2006–2008 (with another 13 aircraft on option). The A340s are valued at £2.3bn at list prices, but Virgin Atlantic will have negotiated a steep discount on this. Three aircraft from the order are to be leased from ILFC on 12 year contracts, and they will join seven other aircraft in Virgin Atlantic’s fleet on lease from the US lessor.

These join the six A380s (and six options) that Virgin Atlantic ordered in February 2001, which will be delivered between May 2008 and February 2010. Originally the aircraft were to be delivered from the summer of 2006, but the date was delayed by an initial 18 months due to problems with suppliers of interior cabin equipment and delays in facilities at airports, although the delivery schedule has since slipped even further. Virgin Atlantic’s A380s will be in a 555–seat configuration and are due to be used on routes to New York, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, Sydney, Tokyo, Washington DC and Johannesburg. In total, the fleet will rise to 36 aircraft by February 2006 and to 39 by the end of 2006.

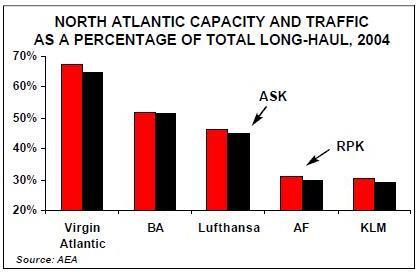

The extra staff and aircraft will be used primarily for the launch of a series of new longhaul routes around the globe although — crucially — almost all of them will be outside of the transatlantic sector. In 2004 no less than 65%of Virgin Atlantic’s capacity and 67% of its RPKs came from North Atlantic flights, a significantly higher proportion of total long–haul capacity and traffic than at any of its main European rivals (see chart, right).

Steve Ridgway, CEO of Virgin Atlantic, said in April this year that the airline fully supported the EU’s attempts to strike an open skies deal with the US, and it would undoubtedly benefit from the lifting of foreign ownership restriction in US airlines (see below). However, at the same time Virgin Atlantic’s transatlantic revenues will be hit significantly if more US and UK airlines are allowed to compete on US–UK routes. Virgin Atlantic is already concerned about overcapacity on transatlantic routes, where struggling US airlines have been slashing fares in order to bring in revenue to compensate for dismal domestic turnover, but the situation will get much worse once more than just two US and two UK airlines compete on the transatlantic sector.

New routes

As Virgin Atlantic tries to lessen its dependence on the transatlantic market, the focus is turning to the Asia/Pacific region, the Caribbean, India, the Middle East, Africa and China. A London Heathrow–Mumbai route using A340–300s was launched in March 2005, following the signing of a new, liberalised bilateral between India and the UK in September 2004. Prior to the new bilateral, BA had operated 19 of the permitted weekly frequencies between the UK and India, with Virgin Atlantic flying just three times a week on Heathrow- Delhi via a code–share with Air India (although this code–share deal has since ended).

Following the revised bilateral (on a sector worth an estimated £200m in revenue each year), the UK CAA awarded 10 of the additional 21 frequencies to Virgin Atlantic, seven to BA and four to bmi. Naturally, all three airlines appealed, but in March this year the UK government upheld the CAA’s decision.

However, after another round of bilateral negotiations in the spring, an additional 44 weekly frequencies over the next 18 months were agreed. Despite a suggestion that Virgin Atlantic might operate UK–India routes jointly with bmi, Virgin Atlantic is pushing ahead on its own, and will expand its services to daily flights to New Delhi and Mumbai by December this year. The airline is also looking at other Indian destinations.

A twice–a-week service between London Gatwick and Havana was also launched in July 2005 to tap into rising demand from UK holidaymakers to Cuba, while in the same month a weekly service commenced between London Gatwick and Nassau in the Bahamas.

Both routes use 747–400s. A London Heathrow–Dubai service will also start in March 2006 with A340–600s, the first of what Virgin Atlantic hopes will be several routes on the lucrative London–Middle East market — although Emirates is likely to react very competitively to Virgin Atlantic’s moves. And following a revised bilateral between UK and Jamaica, a Gatwick–Montego Bay route will launch in July next year, using 747–400s.

These two definite new routes will bring to 28 the number of destinations served by Virgin Atlantic. Virgin Atlantic has been operating between London and Shanghai since 1999, and on October 30 this year boosted the route to a daily service. The increased frequencies were made possible by the Chinese government’s listing of the UK as one of its "Approved Destination Countries" (which enables many more Chinese tourists to visit), part of the government’s liberalisation policies (see Aviation Strategy, September 2005).Virgin Atlantic believes there is great potential for UK–Chinese travel — but so does BA, and it launched a five–times–a-week Heathrow- Shanghai service in June. Virgin Atlantic also plans to launch a daily London–Beijing service at some point in the near future.

However, Virgin Atlantic’s long–haul expansion plans have not all gone to plan. Following a new bilateral between Hong Kong and the UK to allow fifth freedom rights to Australia, in December 2004 Virgin Atlantic launched a daily London Heathrow to Sydney route via Hong Kong, using A340–600s, which it wanted to increase to two flights a day.

Routes to Australia had long been a target for Virgin Atlantic (in order to challenge BA/Qantas on what is a very profitable route) and the airline also wanted to launch a route to another Australian destination — most likely Melbourne or Sydney. But Virgin Atlantic’s performance on the so–called "Kangaroo route" has been poor.

In April outbound flights had an average load factor of just 36%, and incoming flights achieved a paltry 33%. Following a two–for one offer on economy seats to Hong Kong, load factor on the route has reached at least 50% in both directions, but according to a Virgin executive the airline was unprepared for the level of competition on the Sydney- Hong Kong route. Rivals Cathay and Qantas increased capacity in response to Virgin’s entry, and almost 1,000 extra seats a day are now available on the sector. This forced Virgin Atlantic to significantly restructure its pricing policy this summer, with a reduction in some fares by as much as 50%. It’s unlikely the route is making a profit at the moment, although in July Virgin Atlantic commenced code–sharing with Australian–based Virgin Blue on beyond flights from Sydney to six Australian destinations.

One of these is Melbourne, which has long been a target for Virgin Atlantic following demand from business travellers, though a direct service has been hampered by a delay in getting traffic rights. The current Australia- UK bilateral allows 28 flights per week from British airlines, of which Virgin Atlantic has seven and British Airways 21.

Qantas operates all 28 of the Australian capacity. Virgin Atlantic complained to the Australian regulator about an extension of BA’s alliance with Qantas, but the regulator turned down the appeal. Instead, Virgin’s hopes depend on talks held this summer between Australia and the UK on expanding the bilateral. An expansion of flights is even more crucial given that local analysts are uncertain as to how many of Virgin Atlantic’s business passengers will want to transfer onto Virgin Blue flights, which is a single–class LCC operation.

A Manchester–Barbados service is also possible before the end of the year, while frequencies are being increased on a number of routes by the end of 2006, including to Shanghai, Las Vegas, Orlando, Port Harcourt, Dubai and Jamaica. Other new destinations under consideration include Mauritius, the Seychelles and Rio de Janeiro.

Virgin Atlantic is also revamping its portfolio of code–share and frequent flier partnerships. Codesharing began with America West (now US Airways) in 2004 on domestic US routes operated to/from four of Virgin Atlantic’s eight US destinations (Los Angeles, San Francisco, Las Vegas and Washington Dulles).

Virgin has been code–sharing with Continental on North Atlantic flights since 1998, and the airline also code–shares with bmi, Malaysia Airlines and Singapore Airlines. An existing interline deal with South African airline Nationwide was replaced on October 31 this year by a domestic code–share and frequent flier agreement with South African Airways on beyond destinations from Johannesburg.

A key part of Virgin Atlantic’s expansion plan is to almost double the number of passengers it will be able to handle at London Heathrow by 2012, following a deal struck with airport operator BAA earlier in 2005. The first part of the expansion will be completed by BAA by 2008, when Virgin Atlantic’s first A380 will be delivered, and the work will be competed by 2012, when the airline will be able to handle 5.5m passengers a year at Heathrow (compared with 3m at present).

Although not part of the Virgin Atlantic group, Branson has other substantial airline interests, though they have met with varying degrees of success. Virgin Express, Branson’s attempted European LCC, was a failure strategically (see Aviation Strategy, April 2004) and is merging operations with SN Brussels Airlines this year. And Branson’s other current aviation investments are meeting with variable success too.

Virgin America: delay after delay

Virgin America intends to be a LCC that will now commence operations sometime in the first half of 2006. However, the airline’s launch has been delayed several times already, and it originally intended to start way back in 2003 (under the name Virgin USA).

In April of that year Branson declared that the airline would be launched "within six months" — once $150m was raised from venture capitalists — while in early 2005 Branson said the launch financials were in the final contractual stages. However, both times Branson’s optimism has proved to be wrong.

Branson now says that "it has taken slightly longer than thought to get suitable investors on board because we are giving away control of the Virgin brand in the US. We've got to pick someone who can do the job well." But it may be that the delay is due to a lack of financing, although the launch team may be facing a host of other problems too. For example, Virgin America is likely to face opposition from unions and politicians over the impact to weaker US carriers from a LCC in which a foreign company holds up to 49% of the equity (although it can have no more than 25% of voting rights according to current US regulations).

Unions are fully aware that Branson cited US foreign ownership restrictions as a reason that Virgin did not invest in Jet Blue Airways in the late 1990s. Last year the giant AFL–CIO union wrote a letter to Congress in which it alleged Branson had an agenda to "gut US laws that limit foreign control and ownership of US airlines and that bar foreign air carriers from servicing domestic point–to point markets in the US". The letter went on to warn that "we will strongly oppose any rule–bending that harms airline workers".

US airlines are also reacting aggressively towards the perceived threat of Virgin America. Alaska Airlines, for example, told its employees that it would be "all over it [i.e. Virgin America] defending our territory", and that "if they attack our routes, we will meet and match them at every turn". Most concern though must be felt at United, which has a hub at San Francisco (Virgin America’s proposed operational base). Interestingly, Southwest moved its operations from San Francisco to Oakland in 2001 after citing delays and poor turnaround times at San Francisco airport.

For the moment though, both unions and airlines are waiting for Virgin America to launch. Surprisingly, there has been no official press communication from Virgin America since July 2004. This deafening silence followed a host of announcements in the first half of that year, including the appointment of Frederick Reid as Virgin America’s CEO. Reid resigned as COO and president of Delta in early 2004 after being overlooked for the CEO position at the US carrier, and must have been looking forward for a rapid expansion of Branson’s new airline, particularly given the June 2004 announcement that Virgin America had ordered 105 A320 family aircraft. This included 11 A319s and seven A320s, (with options for 72 further A320 family aircraft) as well as 15 additional new A320s to be leased from GECAS.

The firm Airbus order was to be delivered from early 2005, but that obviously hasn’t happened, and some US–based aviation observers believe Virgin America is highly unlikely to be able to launch even in the first half of next year.

Question marks have also been raised over Virgin America’s proposed "split personality", with operations based at San Francisco and corporate headquarters based in New York — which must hold the record for the longest distance between the operational and corporate HQs of any airline in the world. The split presence is less to do with logic than local government incentives, with the state of California contributing a reported $15m in benefits towards the San Francisco operation and the city and state of New York offering $11m for the corporate base. Between them, the two bases will employ up to 3,000 staff, when — or if — the carrier is launched.

Virgin Nigeria: brave joint venture

In October 2004 Virgin Atlantic agreed a deal with the Nigerian government to launch Virgin Nigeria Airways. The government had been trying to launch a new flag carrier since the collapse of Nigeria Airways in May 2003, but previous attempts had failed (see Aviation Strategy, July/August 2004).

In 2004 the plan was for the airline to be called Nigerian Eagle Airlines and be launched in October of that year, but after talks with proposed partner South Africa Airways stalled during the summer, the government approached Virgin Atlantic. Branson’s airline still had to compete against SAA in a final shortlist to win the joint venture deal, but the success of its London–Lagos route launched in 2001 is believed to have been influential in the government’s decision to choose the UK carrier as its strategic and technical partner. Virgin Atlantic owns 49% of the airline, with the other 51% being held by Nigerian institutional investors. The Lagos–based airline has its own management team, employs 1,000 staff in Nigeria and currently operates a fleet of three Airbus aircraft. Virgin Nigeria’s first route was Lagos–London Heathrow, started in June this year with an A340–300 transferred from Virgin Atlantic, while two A320s are used for routes from Lagos to Abuja, Port Harcourt and Accra (Ghana).

The A320s are temporary, as they will be replaced by 737–300s, the first of which will be delivered in December 2005. The airline aims to increase its fleet to 11 aircraft by the end of 2006, with seven 737s and four A340s.

These aircraft will operate on new regional routes within western and southern Africa (such as to Johannesburg and Douala in the Cameroon), while on long–haul the airline wants to operate the US (New York and Houston are under consideration), Asia, Europe and the Middle East (Dubai is a target).

Altogether the airline plans to have a network of more than 15 routes by the end of next year. Virgin Nigeria is also aiming to become profitable from 2006 onwards, and — according to Branson — if the airline is successful the joint venture concept could be extended into other west African countries.

Virgin Blue: the lost shareholding

The Australian–based LCC was launched by Branson in August 2000 and today operates a fleet of 47 737–700s and 737–800s to more than 30 domestic destinations, as well as to New Zealand and selected Pacific islands. It has grown to become the second biggest airline in Australia after Qantas, with an estimated 30% share of the domestic market. Even though Virgin Blue issued a profit warning in August, saying that net profits for the 12 months to end of September 2005 were likely to be in the US$67m- US$76m range (compared with US$120m in the previous financial year) — due to higher fuel prices and increasing competition from airlines such as Jetstar, the LCC launched by Qantas — the airline must be considered a huge success. But the Virgin Group controls only 25% of Virgin Blue.The airline was set up as a 50:50 joint venture between the Virgin Group and the Patrick Corporation, an Australian transport conglomerate, but in December 2003 Virgin Blue carried out an IPO, with Virgin’s stake falling to 25% and Patrick’s to 45%. But Branson appears to have made a strategic error in allowing the Virgin Group’s stake to drop much lower than Patrick’s, because in January 2005 Patrick announced a takeover bid for the whole of Virgin Blue — a bid that took the Virgin Group by surprise and which it resisted strongly. Although ideally Patrick wanted to take 100% control of the airline, it still managed to increase its stake to 62.4%. That gives Patrick effective control of the airline — albeit it with an upset and troublesome minority shareholder that does not want to sell its stake.

Indeed in August this year the Virgin Group said it was supporting an attempt by Toll Holdings — another Australian transport conglomerate — to take over Virgin Blue. Branson said that if successful, the bid would allow the Virgin Group to increase its stake to 41% and "take a more active role in Virgin Blue’s strategic direction". He added: "As a minority shareholder we have been somewhat frustrated by the delay in implementing new business initiatives such as the frequent flyer programme and the decision made not to hedge Virgin Blue’s exposure to fuel prices."

Given that Branson now regrets selling down Virgin Group’s stake, why did he do so in the first place? A clue comes from sale of 49% of Virgin Atlantic (for £600m) to Singapore Airlines in April 2000, which revealed just how vital the cash–generating airlines are to the entire Virgin empire. In 2000 an investigation by the UK’s Economist newspaper revealed that the Singapore sales effectively saved Branson’s music retail chain from bankruptcy. The Economist stated:

"As Virgin’s finance chief admits, without the money from SIA Virgin would have had to approach the trustees of Branson’s offshore family trusts, which are the ultimate controllers of his companies. The financial position of these private trusts, based in the Channel Islands, is secret … The trusts would have lent the money and it would have been repaid out of the bumper cash flow that Virgin Atlantic rakes in during the busy summer months. One way or another, the airline was to be the ultimate source of the cash." So as much as Branson is attracted to the excitement of the airline industry, he is also pragmatic enough to milk successful airlines as cash cows when needed.

Virgin Blue is keen to export its business model to other parts of the Asia/Pacific region. In January 2004 Virgin Blue launched Pacific Blue, a New Zealand–based LCC that uses three 737–800s on routes to Australia and Pacific islands. Based in Christchurch, the airline used the "Blue" name since Virgin Blue does not have the legal right to use the Virgin brand outside of the Australian market. Virgin Blue is also now launching Polynesian Blue, in partnership with the West Samoa government, to take over the international routes previously operated by flag carrier Polynesian Airlines, but now to be operated under a LCC strategy. Routes from Apia to Auckland and Sydney were due to launch in late October/early November using 737- 800s crewed by Polynesian Airlines' staff. Virgin Blue and the government each own 49% of Polynesian Blue, with the last 2% held by "an independent Samoan shareholder".

New airline opportunities

As well as long–haul expansion, Virgin Atlantic and Branson are scouring the globe for other start–up opportunities. Branson says he is advanced in his plans to launch another airline in Australia, this timed focussed on the Australia to US sector (particularly to Los Angeles), as well as to Japan and China. A CEO is being hired at the moment and according to Branson the airline is set to launch by the end of 2005, with Virgin owning up to 49%, with 51% held by a local investor.

The move by Branson to set up a transpacific airline comes after Virgin Blue decided to focus on a domestic network — although given the relationship between the Virgin Group and Patrick (see above), it would come as no surprise if the new airline competed against Virgin Blue in the long–term.In the shorter–term, a new transpacific airline will face fierce competition anyway.

Qantas operates to Los Angeles from Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne (and will operate A380s on the sector later this decade). Singapore Airlines also wants to operate routes between Australia and the US, and is unlikely to be influenced by its 49% stake in Virgin Atlantic. Much depends on whether the Australian government is prepared to give Singapore fifth freedom rights, which puts Branson in the delicate position of either explicitly or implicitly lobbying against the interests of Virgin Atlantic’s minority shareholder.

Elsewhere, India has long been a target for Virgin, and in July 2005 Richard Branson promised that an investment of up to $50m would be made into an Indian domestic airline within the next six months, presumably an existing carrier given the number of new LCCs now in the Indian market. However, since the Indian government does not permit foreign airlines to invest in its carriers, the stake will be made in a personal capacity, most likely being held by one of the myriad of offshore companies/trusts that Branson controls.

China too is on the Branson radar, and his development team are believed to be examining at several possibilities in the Chinese market — although it’s unlikely that the Chinese government’s liberalisation drive could extend to a Virgin China in anything other than the long–term.

Atlantic outlook

While Branson is pressing ahead on several fronts in establishing new airlines, what’s clear is that he tends to be too optimistic about timescales. However, the success (or otherwise) of new Virgin airlines around the globe and held by other parts of the Virgin empire will not particularly affect the future of Virgin Atlantic. Rumours persist that Virgin Atlantic would like to merge with bmi in order to challenge British Airways even more keenly. The airline is believed to be interested in acquiring the 30% stake in bmi that Lufthansa may want to sell (see Aviation Strategy, May 2005), although some analysts believe this is no longer a possibility given Virgin Atlantic’s ambitious organic growth plans. Maybe — but Branson may also be hedging his bets, since by building up the perceived strength of Virgin Atlantic he will be in a better position to negotiate the best deal for Lufthansa’s bmi stake in the future. Much depends on Virgin Atlantic’s performance in the 2005/06 financial year, in which management says profits will increase.

Sources suggest Virgin Atlantic’s figures for the first quarter of the 2005/06 financial year (March–May 2005) have been according to plan, but it is believed that rising fuel costs will have hit second quarter results. An overall increase in profits for the year is a brave prediction given the challenge of rising fuel costs. In the 2004/05 financial year fuel costs totalled £293m, against a budgeted expenditure of £233m, and a fuel surcharge introduced in May 2004 only recovered £20m of the extra £60m fuel costs experienced during the year. Perhaps this is one reason why Branson is now apparently launching Virgin Oil, which plans to build an oil refinery in the UK.

This financial year, fuel costs could top the £400m mark. In June Virgin Atlantic increased its fuel surcharge from £16 to £24 per sector on all tickets sold in the UK, and in September raised it further, to £30. Again however, this is likely to only recover part of the extra costs.

Virgin Atlantic is pushing ahead with a cost–cutting programme that is targeting to save £50m by the 2006/07 financial year, but much of the planned savings are to come from renegotiated contracts with suppliers. Substantial savings may be hard to achieve; for example, one of the biggest suppliers to Virgin Atlantic is Gate Gourmet, the in–flight meals provider that is undergoing substantial financial problems (and in current contract negotiations with British Airways is insisting that its prices go up, not down, as Virgin wants). And there is a risk that the dash for non–transatlantic growth will hit the bottom line. Altogether the next 12 months will be a challenging time for Virgin Atlantic.

| Fleet | On order | Options | |

| A340-300 | 8 | ||

| A340-600 | 10 | 15 | 13 |

| A380 | 6 | 6 | |

| 747-400 | 13 | ||

| Total | 31 | 21 | 19 |