bmi: who's going to be holding the baby?

May 2005

bmi broke back into pre–tax profit in 2004 after two years of losses, yet two of its three shareholders are believed to be seeking an exit. Does shareholder uncertainty imply the future for the bmi group is less than secure?

bmi’s origins date back to 1938, but the airline was named British Midland Airways in 1964 before turning into bmi in 2002. Today the bmi group comprises bmi (the main airline), bmi Regional and bmibaby (its LCC), and altogether it operates a fleet of 59 aircraft out of the UK.

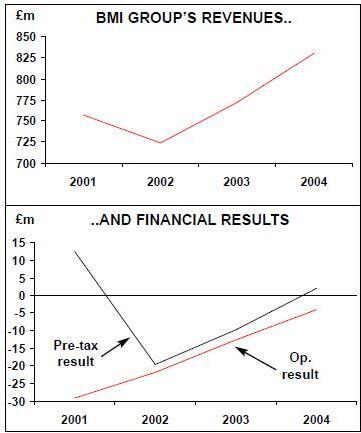

Run conservatively by management, the airline made steady — if unspectacular — profits through the 1990s (see Aviation Strategy, March 1998). However, following September 11, the group posted a pre–tax loss of £19.6m in 2002 — its first pre–tax loss in a decade. In 2003 passengers carried rose 25%, resulting in a 6.6% rise in revenue to £772m and a trimming of the pre–tax loss to £9.8m, although the Gulf war badly affected transfer traffic from bmi’s Star alliance partners at London Heathrow, costing the group around £17m.

In addition to external shocks, the group has also been affected by increasing competition from the LCCs. In the late 1990s, Austin Reid — CEO at bmi since 1985 — was sceptical about the challenge of the low cost carriers, arguing that there was very little evidence that the LCCs were making money.

Reid resigned in October 2004, a year earlier than planned due to "personal reasons". Although bmi claimed the change was routine, some analysts saw the early exit of Reid as part of an attempt by long–time majority owner Sir Michael Bishop to reestablish greater control over the group.

Nigel Turner, bmi’s CFO since 2001, replaced Reid and his appointment was accompanied by an overhaul of the group management team.

This included the appointment of bmi legal affairs director Tim Bye as deputy chief executive and bmi Regional managing director Alex Grant as chief operating officer. Following the management changes, in January this year bmi group launched a wide–ranging strategic review, including an analysis of European routes out of London Heathrow as well as of long–haul strategy.

The review was initiated just before bmi group reported a pre–tax profit of £2.1m for 2004 (see graph). Turnover in 2004 rose 7.6% to £830m, based on an 11% increase in passengers carried, to 10.5m.

Group ASK growth of 7% in 2004 was outstripped by a rise in RPKs, resulting in load factor increasing by three percentage points to 70%. However, at an operating level the group recorded its fourth consecutive year of losses, partly due to rising fuel costs. Even after hedging more than 80% of its fuel needs in 2004, rising fuel prices cost the group £11.1m, although half of this was recovered through passenger fuel surcharges (which were raised yet again in April this year). But results would have been far worse if it wasn’t for a major cost cutting push.

Cost push

Called Blue Sky, bmi group’s cost–cutting initiative aims to reduce costs by £100m over the three–year period to the end of 2006, with £34m in savings targeted in 2004, £26m in 2005 and £40m in 2006.

The 2004 target was achieved, with savings coming from fleet harmonisation (an all–Embraer fleet at bmi Regional and an all–737 fleet at bmibaby), better aircraft utilisation and the introduction of self–service check–ins. bmi also closed its call centre at East Midlands airport in 2004 after the number of calls handled fell by 40% in three years, thanks to the rise of internet bookings. bmi’s website was redesigned and relaunched in the summer of 2004, complete with a new internet booking engine.

This was part of a consolidation of a number of IT contracts into one central outsourcing contract with Fujitsu Services, in a 10–year deal worth an estimated £60m. Interestingly, this partly includes variable payments — e.g. the fee for Fujitsu’s provision of the website and booking engine depends on the amount of bookings processed through the site. According to Richard Dawson, bmi’s IT director, this will achieve "significant savings" and is part of a philosophy "to correlate prices [i.e. costs] with business activity".

As for labour costs, other than by natural wastage, bmi has promised that cost cutting will not result in job losses among the group’s 4,800 staff, 2,700 of which are employed by the main airline and bmi regional (1,600 of those are based at London Heathrow) and 2,100 of which work at bmibaby. bmi offered a 1.5% pay rise to staff in 2004, which was accepted by all employees other than the pilots.

The British Air Line Pilots Association (BALPA) members at the main airline were reluctant to accept the percentage rise, and an indicative ballot of members last year suggested "overwhelming" support for industrial action if needed. However, after negotiations carried on into 2005, a deal was eventually agreed between the two sides in February, which a union source says "was higher than management’s initial offer".

Overhead costs per ASK fell by 20% in both 2002 and 2003 — perhaps an indication of the bloated nature of bmi group in the first place — and overall unit costs fell by 15% over the same period, and by another 15% in 2004. But again — as with virtually every other airline in Europe — bmi has to continuously drive down costs as yields continue to fall. At a group level, yield fell in both 2002 and 2003, although it did remain level year on- year in 2004. However, bmibaby’s yield rose 4.1% in 2004 and as bmi Regional’s also improved during the year, this means that yield fell yet again at the mainline bmi operation.

Mainline woes

Based at London Heathrow, the mainline bmi is a legacy airline that holds 14% of take off and landing slots at the airport.

These are used on operations to more than 20 destinations across the UK and Europe, although just three destinations were added in 2004 — to Aberdeen, Inverness and Naples.

However, this is precisely the short–haul market targeted so effectively by Ryanair at London Stansted and easyJet out of London Gatwick.

bmi is currently in a long running argument with the UK CAA over a proposed 40% increase in charges at London Heathrow in order to pay for the construction of the fifth terminal. bmi accuses the CAA of a "dereliction of duty" in allowing the airport operator, BAA, to levy the charges for a terminal that will be used by BA, while bmi and its Star partners will be moved to ageing terminals one and two. As well as a reduction in the charges, bmi is lobbying BAA to at least allow Star carriers to combine all their flights into one terminal, thereby allowing "parity" with BA’s facilities.

For short–haul, bmi operates a fleet of 27 Airbus and Fokker aircraft. In February 2004 the first of six A319s leased from ILFC was delivered to bmi, all of which will arrive by the autumn of 2005. The A319s are replacing Fokker 100s and a couple of A321s as part of drive to convert the short–haul fleet into an all Airbus operation, which will be completed this summer. bmi is also looking at the A319LR as a potential aircraft for point–to–point medium–haul routes.

But while fleet harmonisation will improve unit costs, the short–haul mainline operation continues to face increasing competition from the LCCs, not just in London, but also at bmi’s other main UK base, East Midlands airport, where easyJet and Ryanair are building up their route network. And there is always the challenge of British Airways, which is becoming much more price competitive on short–haul Europe routes.

Competition contributed to a decline in business class passengers on bmi’s mainline Heathrow routes in 2004, and fare wars are so fierce that one of the options under consideration by the bmi group in the current strategic review is turning short–haul mainline operations into a one–class product.

British Midland was a pioneer of business class on European routes, yet bmi is finding that over the last few years business travellers have not just switched from business class to economy as a temporary measure, but as a permanent trend.

This highlights bmi’s key strategic problem that it cannot fully take advantage of the group’s major asset — the slots at London Heathrow. With business class passengers and yield falling on European routes, the airline would love to switch valuable slots over to long–haul operations. Yet it has long been frustrated in its ambition to launch services on the lucrative UK–US sector out of London Heathrow by the Bermuda II bilateral, which restricts the number of airlines on the sector to four, with BA and Virgin being the designated UK carriers.

After receiving three A330s in 2001 — but failing to win rights to operate out of London Heathrow to the US — bmi instead launched long–haul operations out of Manchester to Chicago and Washington DC in the summer of that year. These are both hubs for United, which bmi has code–shared with since 1992.

The two routes made a loss of around £1m in 2003, but are believed have been close to break even in 2004. Last year bmi built on these initial services through the launch of routes to Toronto in April in co–operation with Star partner Air Canada, and to Las Vegas in October. Routes from Manchester to three Caribbean destinations — Barbados, St Lucia and Antigua — also started in November 2004 (and are reaching load factors of 80%).

The launch of five routes in 2004 ensured that even with vastly better aircraft utilisation (there are now more than 40 flights a week out of Manchester), the long–haul business was again unprofitable in 2004.

The Star alliance is crucial to bmi’s longhaul business — interline revenue totals more than £100m a year, though with United and Air Canada in financial trouble, the dependence of bmi on interline traffic from these carriers at Manchester is worrying. That’s why the US still remains the major long–haul target for bmi out of London Heathrow, particularly as the UK accounts for 40% of all traffic between the US and Europe.

In the meantime, bmi’s first–ever longhaul route out of London Heathrow will start in May with a service to Mumbai — although initially not with the number of frequencies that bmi wants. After the UK and India signed a liberalised bilateral in September 2004, bmi, Virgin and BA applied for 21 additional weekly frequencies between the countries at a UK CAA hearing in December.

Previously, BA controlled all 19 of the authorised weekly services between the UK and India, while Virgin Atlantic operated three times a week on London–Heathrow–Delhi via a code–share with Air India. In a market that it estimated to be worth £200m a year in revenue (with UK visitors accounting for 16% of all travellers to India), bmi wants to operate a daily service to Mumbai and six times a week to Bangalore, and told the CAA that it would undercut BA’s current fares by 10%.

bmi was therefore unhappy with the CAA’s decision to allocate bmi just four flights a week to Mumbai out of London Heathrow, with 10 weekly flights going to Virgin (which will now operate the route itself following the expiry of its code–share with Air India) and another seven to BA. bmi — along with BA and Virgin — appealed against the decision, but in March the UK government upheld the CAA’s allocation, However, the UK and Indian governments started another round of bilateral negotiations in April, and they quickly agreed to increase the number of frequencies between the countries by another 44 flights a week over the next 18 months. bmi is confident it will operate a daily service within that timeframe, but despite a suggestion that bmi and Virgin should in the meantime co–operate on a joint route, bmi insists it will launch the route on its own in mid–May.

The Mumbai service will be followed later in the summer by a three times a week service between London Heathrow and Riyadh, which bmi hopes will pick up demand no longer served by BA since it axed its Saudi Arabia routes in March due to security issues, which it said was hitting profitability.

However, these two routes will severely stretch bmi’s long–haul capacity, as it has just three A330–200s. bmi did hold options for further A330s, but these were given up.

bmi plans to damp lease a 757–200 (i.e. bmi will provide cabin crew) from Icelandair for the Manchester–Washington DC, which will free up an A330 to serve the Mumbai and Riyadh services. This is not ideal, however, as on the Washington DC route the 189–seat 757 will provide less capacity than the 244- seat A330, and with the addition of the route to Riyadh the group will have to add permanent long–haul capacity. Another complication comes from the need to get approval from the US FAA for the Icelandair damp lease deal on the Manchester–Washington DC route — until approval is given, bmi will have to temporarily suspend its code–share with United on the service, using only its own designator instead.

bmi is also considering long–haul routes to South Africa, possibly in co–operation with fellow Star member SAA. bmi already code–shares with 20 airlines — last year code–sharing was started with Singapore Airlines and Sri Lanka, while an existing code–share with Gulf Air on UK flights was extended to selected European routes in October 2004, a move that indicates that Gulf Air may join the Star alliance in the future. bmi also started code–sharing with fellow Star member US Airways in October 2004.

bmi Regional

Aberdeen–based bmi Regional operates three Embraer 135s and 10 Embraer 145s on regional routes. As part of bmibaby’s launch in 2002 (see below), all of bmi’s regional routes out of East Midland airport were transferred to the LCC. However, due to lack of demand, some of these services have now been transferred back to bmi Regional, the latest being routes to Paris CDG and Nice, which bmi Regional took over in March 2005.

In November 2004 bmi Regional restarted group operation to London City airport after a 13–year absence through the launch of a four–times daily route to Leeds Bradford.

The service used an ATR 42 leased from Air Atlantique, but although bmi Regional said it had plans to develop routes and services out of the airport using its Embraer 135s, at the end of April the Leeds Bradford route was abruptly suspended due to low demand, caused by "the type of aircraft used".

Whether further routes will be launched from the airport is now open to doubt. The bmi group describes bmi Regional’s performance in 2004 as "satisfactory", with passengers carried increasing last year, although load factor fell "marginally".

bmibaby

In 2001 Austin Reid, then the CEO of bmi, said that the airline would never launch a LCC as "going from a full service to a budget airline is almost impossible".

That view rapidly changed once Go launched operations at bmi’s base, East Midlands airport, in 2002. In March that same year bmibaby was launched at the same airport using a fleet of three 737s borrowed from the main airline.

At that point bmi announced it was adopting a "segmentation strategy", based on separate products for different segments — the mainline bmi airline for European short–haul and long–haul; bmi Regional; and the new LCC.bmibaby didn’t get its own air operator’s certificate until March 2004, which meant that it did not have operational independence from its parent until that date, but today bmibaby operates to 20 destinations out of six UK airports — East Midlands, Manchester, Teesside, Cardiff, London Gatwick and Birmingham — with a fleet of 10 737–300s and six 737–500s transferred over from its parent.

The LCC will dispose of the 737–500s in favour of an all 737–300 fleet by the end of this year, a model that has larger seat capacity. Three 737–300s were added to the fleet in December 2004, on lease from ILFC, and following the launch of routes from Birmingham International airport in January this year — which increases bmibaby’s route network by more than a third — the airline will lease further 737s in the summer.

Five aircraft will be based at the Birmingham hub (where 150 jobs were created) by the summer, where currently bmibaby operates 12 routes — to Alicante, Amsterdam, Belfast International, Bordeaux, Cork, Edinburgh, Geneva, Knock, Malaga, Murcia, Palma and Prague — with another eight being added by the summer schedule.

Altogether, bmibaby expects to carry more than 1m passengers out of Birmingham in 2005.

Although Flybe and MyTravelLite are based at Birmingham airport, easyJet doesn’t have a presence and Ryanair has just one route. However, this wasn’t the case at London Gatwick, where bmibaby’s attempt to establish a hub in April 2004, with plans for at least 10 routes, was a failure. The operation was shut down at the end of 2004 in favour of the new base at Birmingham, bmibaby having learnt the hard way that directly taking on easyJet — as well as being in indirect competition with the mainline bmi operation at London Heathrow — was a mistake.

bmibaby carried 3.2m passengers in 2004, 16% up on 2003, and the LCC expects to break the 4m barrier in 2005.

Load factor rose from 71% in 2003 to 78% last year, after a 9% capacity increase was met with a double figure growth in RPKs.

Although bmibaby made a loss in 2003, it is thought to have been close to break even in 2004 after yields rose, a trend that is continuing into 2005 (yield was up 5.2% in January this year compared with the same month in 2004).

To keep up momentum at bmibaby, David Byron, who has been with the bmi group for four years, was appointed managing director in January, replacing Tony Davis, who became CEO of Singaporean LCC Tiger Airways. Last year bmibaby also agreed a partnership with LCC Germanwings — controlled by bmi’s Star partner Lufthansa — with co–operation on sales outside their home countries.

The bmi group claims bmibaby has a similar cost base to easyJet, and in terms of fleet utilisation there is a significant difference in operations between bmibaby and the mainline operation. Aircraft utilisation is approximately 25% higher at the LCC than the main operation, while pilot hours are up to 33% longer at bmibaby.

Uncertain future?

If bmibaby moves into profit in 2005, it has been suggested that a flotation or trade sale is a possibility. That appears unlikely though, as it increasingly appears as if the LCC is becoming the key success story at the Group, out–shadowing the continuing weak performance of short–haul operations within Europe at the mainline bmi.

The Group admits that "bmibaby has had an important role in absorbing part of the overhead cost of the group, which otherwise would have had a detrimental effect on our mainline operation". In the future, long–haul may generate substantial profits, but this is heavily dependent on bmi being able to better sweat its key assets — the Heathrow slots — through more routes.

According to Bishop the main airline has "turned the corner" and the group is on track to both meet the 2005 cost–saving target and make an operating profit this year. bmi also points out that at the end of 2004 the Group’s debt stood at £122m, compared with debt of £181m at end 2003, while cash totalled £139m at end 2004, compared with £120m a year earlier. But it was interest on that cash pile that turned the operating loss in 2004 into a pre–tax profit, and if the group was floated then surely shareholders would demand that either the cash pile was invested in a suitable opportunity or returned to investors as a dividend.

And despite the massive cost–cutting effort and new senior management, the bmi group looks weak strategically, with a tiny long–haul network and with short–haul being squeezed by the LCCs.

There are marketing problems too, particularly with bmi’s image — or rather the lack of one. In 2004 bmi commercial director Adrian Parkes admitted at a meeting with UK travel agents that: "People know what they are getting with Ryanair and Virgin — they don’t with us." bmi’s market position has not been helped by the name change from British Midland, nor by the segmentation strategy, which offers the public three different bmi brands.

Shareholder flight?

Sir Michael Bishop owns 50% plus one share of bmi group, Lufthansa has a 30% minus one share, and SAS owns 20% — yet the two external shareholders are unhappy with the performance of the group, and are believed to be looking to sell their stakes.

Part of the reason for this is that bmi, Lufthansa and SAS pool revenues and profits on their routes between the UK, Germany and Scandinavia (and a few other destinations) under the so–called "European Cooperation Agreement".

Under this pooled deal, although bmi operates most of the included routes it absorbs only 10% of losses, whereas SAS and Lufthansa each take 45% of losses. According to SAS, the pooled routes made a collective loss of £23m in 2004 (compared with a £42m loss in 2003), though bmi’s share of this under the pooling agreement is just £2.3m. SAS now says that the pooled agreement is "unsuitable", and that when it expires at the end of 2007 SAS will not renew it. In any case, according to Jorgen Lindegaard, CEO of SAS group, "we probably wouldn’t even get acceptance in Brussels for continuing this sort of co–operation."

bmi admits it wants the pooled agreement to perform better, and that the deal is being examined as part of the current review of mainline operations.

This review will be shared with SAS and Lufthansa, bmi says, and it is confident the pooled deal will be much more attractive by the end of 2007.

This appears to be a significant difference between SAS and bmi, and even if bmi offered to change significantly the cost allocation in any new deal, the Scandinavian airline appears determined to end its association with bmi as soon as possible. SAS says it has "no strategic interest" in bmi, and says that "financial assets should be sold if you don’t see a return on those assets" — although in March SAS said that the airline had not yet received any offers for its bmi stake.

Lufthansa too is believed to be trying to sell its stake, to either Virgin Atlantic or British Airways, in order to avoid having to buy Bishop’s 50% plus one share stake that it is legally obliged to if Bishop exercises a put option anytime until 2009, as agreed between the two parties when Lufthansa bought into British Midland in 1999 (for details on this see Aviation Strategy, March 2005). Lufthansa rushed into the 1999 deal — in which it bought 20% of the airline for £91.4m — out of a fear that Bishop would ally British Midland with the SkyTeam alliance (hence securing access to London Heathrow) and as a result entered into obligations that are now looking less than wise from Lufthansa’s point of view.

One put option was exercised in 2002, when Lufthansa bought another 10% stake for £45.7m, and the option for the 50% that Bishop owns would also be at the 1999 price. bmi’s 1999 valuation was £457m, meaning that the remaining put option would cost Lufthansa more than £228m.

That price is well above what most analysts believe to be the true market worth of bmi, and write downs by Lufthansa imply that the value of bmi has at least halved.

However, the launch of routes from London Heathrow if/when an open skies deal with the US is signed would increase bmi’s valuation substantially. The winner in this situation is Bishop, who can hang on to his stake in the hope that a new US–UK bilateral is imminent — but in the event it isn’t, can sell his shares to Lufthansa by exercising the put option.

One way of valuing the airline is on a slot basis, by considering bmi’s 85 slot pairs at London Heathrow. Historical transactions suggest a price of up to £10m a pair (as paid by Qantas in 2004), although the price for an "average" pair of slots at Heathrow is around the £5m level. That suggests a price of around £425m for the slots, which, is close to the 1999 valuation of the airline.

Unconfirmed sources claim both BA and Virgin talked to Lufthansa about acquiring the German carrier’s stake, but both airlines told Lufthansa that because of the Bishop’s put option they did not want to do a deal at present. With BA holding 40% of the slots at London Heathrow, an acquisition of bmi is almost unthinkable from a competition point of view, but a Virgin Atlantic/bmi group merger would make sense strategically.

There’s little doubt that Virgin is interested in acquiring bmi (formal talks held in May 2003 came to nothing after a reported reluctance of Bishop to cede overall control), although the airline continues to refuse to comment on the current situation.

Virgin’s trump card is that there are unconfirmed rumours that Bishop wants to exit his holding sooner rather than later (which he would do by simply exercising the existing put option with Lufthansa).

If Bishop’s intention is true, it means that not one of the three existing shareholders has a long–term commitment to the airline, leaving Virgin a clear run at securing key slots at London Heathrow — providing no surprise bidder emerges.

| Fleet | Order | Options | |

| Mainline bmi | |||

| A319-100 | 4 | 1 | |

| A320-200 | 11 | 1 | |

| A321-200 | 10 | ||

| A330-200 | 3 | ||

| Fokker 100 | 2 | ||

| bmi Regional | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Emb 135 | 3 | ||

| Emb 145 | 10 | ||

| bmibaby | |||

| 737-300 | 10 | ||

| 737-500 | 6 | ||

| Total | 59 | 2 | 0 |