How will the Canadian market evolve?

October 1998

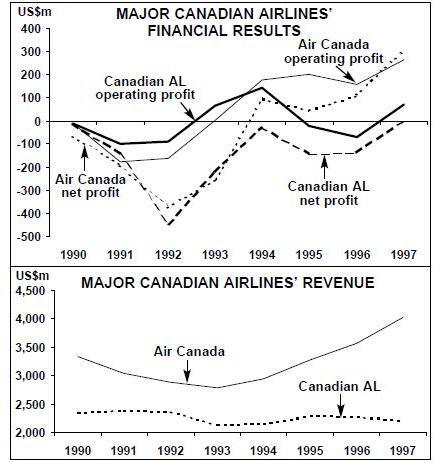

In 1997 there was a unique aviation achievement in Canada: both of the major carriers — Air Canada and Canadian Airlines — reported a net profit. Since then, however, the situation has deteriorated again and now a new entrant — WestJet — poses a new threat to the incumbents.

Air Canada: a European American

Although it had already been privatised for some 10 years when the Canadian industry was deregulated, Air Canada still occasionally gives the impression of a state–supported European flag–carrier rather than an all–commercial North American airline. This was evident during the 14–day pilot strike in September, which completely grounded the carrier.

The pilots ended their action accepting a 9% pay rise over the next two years plus improved conditions — an offer which was on the table before the strike — although the pilots had originally demanded a 20% increase. Much of the argument between the union and the management concerned cross–border pay comparisons, with the pilots claiming that their salaries had drifted well below those at the leading US Majors. Management’s response was that this apparent trend was largely the result of exchange rate changes: the Canadian dollar has fallen to an historical low (64 US cents) against the US currency.

The impact of the strike on Air Canada’s finances is going to be significant. Bottom line losses caused by the strike are estimated at C$290m (US$201m), according to the airline. Although Air Canada reported a net profit of C$427m (US$308m) in 1997, C$201m of this came from the sale of its investment in Continental, so it is no longer certain that Air Canada will be able to produce a profit for the whole year. Moreover, it is almost inevitable that Air Canada will have to concede the same pay rises to the other employees, so increasing its annual costs by about C$60m (US$42m).

There is also the question of winning back its customers. Air Canada’s service reputation was badly damaged by the strike, especially by actions such as turning back aircraft on Canada–Caribbean routes in mid–flight on the day the strike was called. The airline’s immediate response was to offer treble miles on its Aeroplan FFP, a move designed to appease its core customers — the fewer than 100,000 passengers who, according to Air Canada’s own calculations, contribute more than 80% of the airline’s profit.

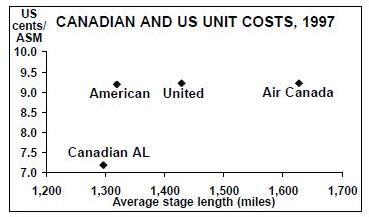

Air Canada’s concentration on the business traveller sector does push up its costs. But it is still clear that its unit costs, taking into consideration the weakness of the currency and its long average stage length, are out of line with its main competitor Canadian and the two mega alliance partners south of the border.

Lamar Durrett, Air Canada’s CEO, has announced various measures to tackle the cost problem, including rationalising the network in the west of the country, shifting more operations to its regional subsidiaries like Air BC, redeploying aircraft on transborder routes and cutting maintenance costs by establishing joint operations with its Star partners.

These initiatives now look inadequate following the strike and the imminent escalation in labour costs. In addition, the fragile, tax–burdened Canadian economy is already feeling the fall–out from the Asian crisis, and the prospect of a recession is now widely feared.

Nevertheless, Air Canada has been remarkably successful in the US–Canada open skies environment, developing a hub avoidance network from Toronto to US cities that regularly uses 50–seat Canadair RJs. It has been protected from full–scale US competition as the agreement initially limited US carriers’ entry into Toronto Pearson.

That protection is now over but Air Canada has succeeded in developing a fortress hub at Toronto — commanding about 70% of the market — as part of its Star alliance strategy. By combining with United it achieves very high market shares on routes to its US partner’s hubs at Washington and Los Angeles, although American’s strong presence at Chicago provided effective competition to AC/UA services. Not surprisingly Air Canada has fared much less well on routes to hostile hubs like Dallas and Atlanta, and has been forced to downscale operations there. US expansion into the Toronto market should be limited to routes that take advantage of their respective hub strengths.

One of the reasons that Air Canada has been able to return profits in recent years was a change in attitude to Canadian Airlines. Air Canada used to compete too strongly against its Calgary–based rival, with the management evidently believing that there was not room for two full–service international airlines in the Canadian market. Air Canada’s actions helped produce a miserable series of results for Canadian (it reported a net loss for every year during 1990–96 and a minuscule profit in 1997), but they also contributed to its own negative results in the mid–1990s.

Canadian’s problems

Canadian, one–third owned by American, has teetered on the edge of bankruptcy several times, notably in late 1996 when it suspended creditor payments for 3–6 months and had to be supported by a fuel tax rebate from the provincial governments of Alberta and British Columbia. 1998 first–half results were again very disappointing (see table, right), raising more doubts about the carrier’s survivability, although it did react effectively to the Air Canada strike, adding 20 flights a day to its domestic network.

Canadian faces three very serious problems. First, its code–share agreement with American enjoys antitrust immunity, but intra–alliance relations are not all that harmonious. Under pressure from its own pilots’ union, American recently forced Canadian to hand over some key transborder operation, so damaging Canadian’s revenue. (Incidentally, one of Canadian’s strengths at present is perceived to be the position of Douglas Carty as CFO as he is the brother of American’s CEO, Donald Carty.)

Second, Canadian’s key strategy focused on building up its Vancouver hub, offering about 120 flights a week to eight of the ten top Asian points. The Asian crisis has evidently put a serious dent in this strategy. Canadian had intended to increase its US–Asia traffic, marketing the CP/AA code under antitrust immunity. Now, however, with Cathay Pacific in the oneworld alliance, Canadian risks being marginalised. The Vancouver hub has also come under attack from Alaska Airlines, although the US airline is expected to retrench.

Third, Canadian faces increasing competition in the west of the country from a new entrant that might just evolve into a northern version of Southwest.

The WestJet threat

WestJet, established in 1994, operates nine 737–200s out of Calgary and has plans to increase its fleet by seven during 1999/2000. It has found a profitable niche serving the VFR market in western Canada. Distances between the western triangle (Calgary, Vancouver, Edmonton) are such that air travel has to be the main mode of transport.

WestJet’s success is that it has been able to stimulate this market even though it defies conventional wisdom by operating at low frequencies (one to five flights a day). An explicit aim is to persuade customers to increase the number of flights that they take.

WestJet employs all the standard strategies associated with successful low–cost operations. It flies an homogeneous 737 fleet, and has so far avoided the temptation of new equipment — the seven 737s it is buying from a leasing company will cost US$30m in total. Sales are mostly direct, with an emphasis on selling through the internet. It tries to project a relaxed image, with humorous messages and adverts.

By its own calculations WestJet’s unit costs are 43% below those of Air Canada or Canadian on a stage length adjusted basis, but it still faces vigorous competitive responses from the incumbents when it enters new markets. They normally match WestJet’s fares within 72 hours — with capacity controls to limit yield erosion — or through offering two or three times normal rewards on their FFPs for travelling on WestJet–operated routes.

These tactics do not seem to be working. As with the Ryanair experience in Europe, the WestJet effect has been to generate new, low–yield markets. And the major carriers, by advertising their own new low fares, have destabilised the economics and value of their premium product.

In 1996, its first full year of operation, WestJet was present on five of Canada’s top 25 city–pairs; on these routes the average traffic growth was 36%. On the 12 city–pairs without any low cost competition average growth was 11.4%. (On the remaining eight routes low cost competition was provided by the now defunct Greyhound; average traffic growth was 15%.)

WestJet has definitely damaged Canadian’s yields and volume in the west, and Air Canada recently announced that it will remove some capacity from markets that WestJet serves.

Possible IPO?

For a start–up, or indeed any airline, WestJet has a solid balance sheet — C$43.5m (US$30m) in equity and C$11.5m (US$8m) in debt at the end of June, and the airline has been consistently profitable in its early rapid expansion phase.

Although a private company — it is owned by its founder, chairman and CEO, Clive Beddoe, who is also chairman of a successful real estate development company, and other managers — WestJet filed in August a “non–offering prospectus” with the Toronto stock–exchange, raising expectations of an IPO.

Stockmarket conditions have of course deteriorated since then, but the move is an indication of the carrier’s ambitions. In the non–offering prospectus the airline often compares itself to Southwest (but then so does every new entrant seeking to raise capital), and speculation in Canadian aviation circles is that WestJet is looking to intensify its campaign in Canadian’s western territory, then expand into the east — Air Canada’s domain.

An objective analysis of the Canadian market (geographically the country is huge but the population is only about 22m, 38% that of the UK) might suggest that there should not be two traditional, full–service airlines. One full service flag carrier plus lower cost, product–differentiated international and domestic rivals is the norm in deregulated European markets.

However, as Tony Hine of First Marathon in Toronto points outs, the eastern city triangle (Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal) is also known as the “Bermuda Triangle” for new entrants: no new entrant has survived in this market.

Expansion in Canada is also complicated by the presence of a large and successful charter sector (as in the UK and Germany, but hardly at all in the US). The main players — Air Transat, Royal Airlines, Canada 3000, and Skyservice — operate in an interesting market. As well as the summer operations to European destinations and transcontinentally within Canada, there are also winter operations from the frozen north to Florida and the Caribbean, creating a second peak that is counter–cyclical to the European market.

Transat is the biggest tour operator in Canada and through a subsidiary owns the third largest tour operator in France plus 50% of Star, a French charter. First Choice set up Air 3000 and its UK charter subsidiary, Air 2000, provides the Canadian airline with capacity.

But, as in Europe, the charters have no serious plans to expand into the scheduled sector (their equipment is the wrong size). If anything WestJet could expand its own charter activity — last year it won a contract from a tour operator for flights to Reno, Palm Spring and Las Vegas. This is a useful supplemental strategy for maximising aircraft utilisation.

It may seem improbable that a newcomer like WestJet could undermine part of the mighty oneworld alliance and change the structure of the Canadian industry, but it does seem to have found a formula that works in that market.

| US$m | Revenue | Operating | Net | Operating | Net |

| profit | profit | margin | margin | ||

| Air Canada | 2,049 | 106 | 45 | 5.2% | 2.2% |

| Canadian | 1,020 | -22 | -57 | -2.1% | -5.5% |

| WestJet | 34 | 3 | 1 | 8.3% | 3.7% |