Identity crisis for Europe's LCCs

November 2010

The Southwest LCC model, as it was adopted in Europe, changed to suit the different operating environment, in particular the high density and concentration of population within the continent and the slow introduction of deregulation. In the early days Ryanair found a niche in generating and stimulating demand from UK regional cities to Ireland; attacking the pent–up VFR demand from the Irish diaspora in England. easyJet, in contrast, initiated domestic UK routes in direct competition with the incumbents, BA and British Midland; and then turned to leisure routes, diverting demand from traditional charter carriers.

Both were able to create a developmental leap forward in the early 2000s negotiating very advantageous deals with the main manufacturers following the equipment order slump after September 2001 – deals possibly never to be repeated. In the process of this growth they both concentrated on the KISS principle; but more importantly, wedded to the idea of pure point–to–point services and operating purely intra–European services, they were able to take advantage – thanks to the slow process of deregulation — of their legacy competitors' inability (or desire) to operate network services from bases outside their home countries. As a result, both have been able to build a series of bases in the main countries of western Europe and pan–European air transport brands, now accounting for some 20% of total intra–European capacity.

There are differences: Ryanair has tended to concentrate on secondary and tertiary airports that can provide the 25 minute turnaround essential to the schedules and special deals on landing fees, relatively low frequency but high number of destinations served from each base; easyJet has tended to be willing to operate at more primary airports – accepting a higher operational cost in the anticipation of higher achievable yields — while operating relatively higher frequencies on individual routes to attract business traffic. As part of the process of chasing ever lower costs the two have been instrumental in “unbundling” the product helping to change consumer expectations and behaviour – even to the point of creating their own self–service hub networks.

Other entrants have followed with variants on the basic principle. Norwegian was able to take advantage of the vacuum provided by the SAS acquisition of Braathens to establish itself as a serious contender against a very high cost competitor in a niche regional market. Vueling started off trying to create a Catalan low–cost contender, and has ended up, after a massive fares war in the Spanish market, merging with Iberia’s affiliate Clickair. Flybe re–created itself as a low fares airline on secondary and tertiary city pairs, operating what otherwise would be termed regional flights on relatively low density aircraft. Air Berlin, originally came to the stock–market in 2006 heralded as the third largest LCC in Europe – although to give them their due, with a substantial level of charter business, they stated that they ran a “hybrid” business model. With the acquisitions of dba, LTU, Balair, Niki and TuiFly, Air Berlin has established itself as Germany’s second largest carrier. Wizz is focusing on central and eastern European services to secondary airport destinations in western Europe – having finally seen off SkyEurope’s attempt to do the same.

Each tries to offer a variety of the LCC model – some operate allocated seating (and charge for extra leg room); some such as Vueling, Norwegian and Air Berlin actively promote transfer routings; some even have FFPs – Norwegian through its own bank to get past the ban on the use of miles on domestic flights; Air Berlin in its pursuit of the corporate business customer has its Top Bonus program; and even easyJet has a possible precursor of a frequent flier club in its annual easyJet Plus card.

Few business models stay static forever. Ryanair has signalled an intention to slow its growth plans dramatically once the last of its current aircraft orders enters the fleet in 2012 (see Aviation Strategy, October 2010). The company has stated that while it will continue its basic opportunistic view of airport destinations, there are more offers coming its way to attract it to more major airports – emphasised by its new operations in Barcelona El Prat – and the management has suggested they would consider moves into any but the top three network hubs. This will no doubt have a knock–on effect on the rest of the industry.

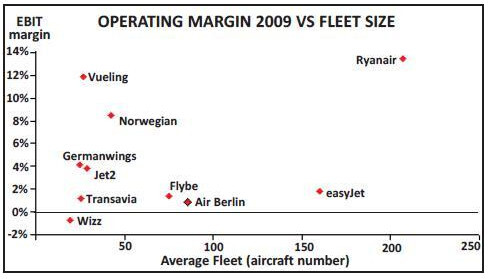

At the same time, easyJet, whose recent financial performance has been well below that of smaller LCCs (see chart, above), is reassessing its direction. With a full change of personnel at board level (unlike Ryanair, easyJet’s top management has rotated several times over the years, with little left of the “orange culture” introduced by Stelios Haji–Iannou and Ray Webster), the new CEO, Carolyn McCall, is expected to announce the result of the company’s strategy review in late November. It was intriguing to note a recent online customer survey on their website asking such questions as whether they should offer allocated seating or even fly to and from Heathrow (assuming they could get slots of course). easyJet has tended to show in its route development a preference to reduce capacity on routes where it is in direct head–to–head competition with Ryanair. With the possibility of pressure from Ryanair providing more competition at primary airports, easyJet may need to consider moving even more to mainstream airport destinations – and so a move into Heathrow (it is already a major player at Paris CDG, Milan Malpensa and Geneva) may not be such a silly idea. Such a move may even raise the question of whether a potential link between them and incumbent BA (or the new IAG holding company) to provide BA’s short–haul feed could be feasible or sensible.

Air Berlin also is moving even further away from the KISS principle of the Southwest model. It of course has built its own complexity – with intra- European hubs in Palma, Berlin Tegel and the congested Düsseldorf; in–flight service; FFP. It signed up with the oneworld alliance earlier this year – giving that global alliance its first real access within Germany. It will start code–sharing with AA this winter, and is set to start code shares with BA, Iberia, and Finnair from the summer of 2011 on all points east, west and south. It will now be able to join in with the alliance’s FFPs and should gain some benefit for its long–haul, ex–LTU operations from the American sales exposure. It has even been invited by BA to move London operations to Gatwick from Stansted in order to improve European feed for BA’s long–haul (admittedly leisure oriented) flights – although it is unlikely to be included within the immunised transatlantic joint venture between AA, IB and BA.

Meanwhile, the latest news from Norwegian is its plans to take two 787s on lease from ILFC in 2012 to pursue its future long–haul operations – the longest sector route in its network at present is the route from Oslo to Dubai, which at 5,100km may just be classified as long–haul (seven–hour flight on a 737!). This may be the next logical step for LCCs with existing effective short–haul hubs to develop access long–haul markets (see Aviation Strategy May 2010).