Lufthansa Group - an empire at its limits?

November 2009

Lufthansa kicked off the European airline profits reporting season for the three months to end of September with a reasonable set of figures in the circumstances. But has the Lufthansa empire grown too complex and unwieldy – or is the time right for further expansion of the Lufthansa Group?

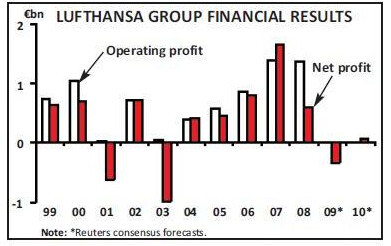

As usual, the numbers were confused by continuing changes in the group’s universe and the seemingly inevitable changes in accounting standards : the nine month figures presented included just under one month’s consolidation of Austrian Airlines (included from September 3rd) and just a quarter from bmi (fully consolidated from the beginning of July). The group’s revenues for the nine month period fell by 13% in absolute terms to €16.2bn and traffic revenues declined by 16%. Without the first–time consolidation of bmi and Austrian, total revenues would have fallen by 16%. Total operating costs meanwhile fell by 6% to €17.8bn (and would have fallen by 8% on a like–for–like basis) – mostly influenced by a 36% drop in fuel costs – and after allowing for a 50% increase in “other operating income” the group produced an operating profit of €316m, down from €936m in the previous year. However, the published operating profit under IFRS includes what normal observers would regard as exceptional or extraordinary items. On an adjusted basis, after taking account of profits on aircraft sales, revaluations, provision movements and write–downs/ write–ups (the acquisition of Austrian generated negative goodwill of around €60m), the underlying operating profits for the nine months were €226m, compared with €994m in the same period for the prior year.

Lufthansa is almost unique in having successfully (so far at least) operated as a conglomerate. The passenger airline division is by far the most important in terms of revenues, but the logistics (i.e. cargo), MRO (or maintenance), Catering and IT Services businesses are all important global businesses in their own right.

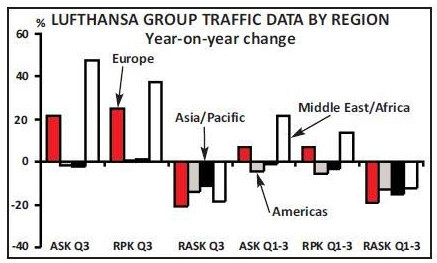

The passenger business in the nine months saw capacity up by 2%, traffic at the same level as the prior year, while yields slumped by 14% and total revenue fell by 12%. Operating profit halved to €239m. For the quarter, benefiting from bmi and one month of Austrian, capacity was up by 9%, traffic by 10% (though this does compare with a strike–affected period last year at LH) but yields down by a massive 17% and total revenues only down by 6%. The operating result for the quarter jumped by 42% to €204m (but will have been helped by the “badwill” from Austrian).

The consolidation of bmi, and to a lesser extent Austrian, causes some difficulty in interpreting the published figures. Both these companies have provided a significant boost to the operations with Europe and to the Middle East, and account for most of the strong growth in capacity seen on those route areas. For the month of September alone, Lufthansa reported a 33% increase in capacity on European routes and a 50% jump in capacity to the Middle East and Africa. Unit revenues were still consistently 10–20% down year on year for the quarter across all regions of traffic. For the three month period bmi provided Lufthansa with a mere €300m of revenue, an EBITDA loss of €14m and an operating loss of €10m – and this is in the main summer season. Austrian on the other hand generated €188m in the month of September, and Lufthansa was able to register an operating profit from its new subsidiary of €38m, albeit helped by a one–off effect of €26m.

The balance sheet at the end of September meanwhile shows deterioration. In the nine months the group generated operating cash flow nearly sufficient to cover its net capital expenditure of €1.5bn. The group is sitting with gearing currently of 80% — well above its long term target of 40–60% — although this does not take into account any capitalisation implied by the aircraft under operating lease, of which the group has 142 units in its fleet. Unsurprisingly both Moody’s and S&P have downgraded their ratings on Group debt – but it is still one of the few investment grade airlines in the world.

Like all airlines at this time of the cycle Lufthansa has introduced a new cost reduction plan – this time under the name “Climb 2011” — to cut costs by €1bn by the end of 2011 and safeguard earnings and cash flow. This seems to include further capacity reductions, an accelerated phasing out of the 50–seater regional fleet, redundancies/early retirements and a further 10% reduction in personnel unit cost, a squeeze on external suppliers, and a promise to “invest in the earning capacity of aircraft” (i.e. increase seat density?) and to renegotiate the delivery of its 136 aircraft on order – including no doubt its 15 A380s. Unlike others, however, it also has to deal with restructuring at two new subsidiaries.

Is the group too large?

Meanwhile, the group restructured the responsibilities of the executive board in May and June this year, bringing in Christoph Franz as CEO of Lufthansa itself and Stefan Lauer as “Chief Officer Group Airlines”. This reshuffle of responsibilities, the group states, provides the necessary organisational steps “for new airlines to be integrated into the Lufthansa airline group”, and gives rise to the suggestion that it will look actively to acquire even more failing European carriers in the apparent drive towards consolidation.Has the group managed to get its hands too full? In several senses Lufthansa is unique: it has built an aviation conglomerate that encompasses but separates operationally the passenger business, cargo, maintenance and catering operations. Within the passenger business it has segmented a product offering by retaining individual brands, without apparently cannibalising its core business. It is also unique in being a major European network carrier heavily reliant on transfer traffic without the benefits (enjoyed by British Airways at Heathrow or Air France at Paris) of a high–density local catchment area and good levels of point–to–point demand. Following the acquisitions of bmi and Austrian, and assuming that it gains a majority of SN Brussels in a couple of years, it will be in charge of a disparate portfolio of some 790 aircraft (see table, left) – substantially greater than great rival Air France–KLM’s fleet of 649.

In the longer run this may provide some substantial cross- benefits of commonality and fleet rationalisation (after all it was SWISS that acquired Austrian’s discarded A340s two years ago when OS rationalised its long–haul network), but in the short–run may appear unwieldy. The three Germanic–speaking carriers – Lufthansa, SWISS and Austrian – all have hubs geographically fairly close together at Frankfurt, Munich, Vienna and Zurich. bmi brings the dubious benefit of access into fortress Heathrow. Sabena provides a pincer into the attractions of the AF/KLM joint hub system between Paris and route rights and strong ethnic flows into Francophone Africa. The others in the portfolio – Eurowings and germanwings (including perhaps the Turkish charter SunExpress, 50% owned with THY) — may appear a pure Germanic solution.

SWISS, fully consolidated since July 2008, was acquired after it had restructured itself towards profitability out of the ashes of Swissair’s collapse, and after all the necessary route rights had been renegotiated. It brought Lufthansa strong operational group benefits in maintenance, cargo and presumably IT. It also brought Lufthansa’s first hub outside Germany, having discovered from the performance of Air France–KLM that there could be strong revenue benefits, for a carrier dependent on transfer traffic, from being able to market routings over a variety of hubs (and cut out a competitor). Even though SWISS’s main base at Zurich is only 300 km away from Frankfurt — and 240km from Lufthansa’s second hub at Munich — there is a sufficient geographic spacing to allow the two to access incremental traffic flows. SWISS accounts for 15% of the total Lufthansa Group’s passenger numbers and a slightly lower proportion of total capacity (in ASKs).

germanwings is Lufthansa’s in–house LCC and operates a fleet of 27 A319s to 47 European destinations primarily from Cologne and Stuttgart, but also has small bases in Berlin, Hamburg and Dortmund. In 2008 it started negotiations with TUI to consider a merger with its LCC Hapag Lloyd Express/TUIfly, but shied away to allow Air Berlin to take over the troubled operation. There are very few full service airlines that have successfully operated an LCC, but Lufthansa obviously sees this as a matter of branding and a way of accessing the non–corporate traffic on routes that bypass its main hubs in Frankfurt and Munich (and of course fending off incursions from outside Germany); but at the same time must be very nervous of ensuring that there is no cannibalisation of its own traffic base. It appears that some rationality has returned to the domestic German airline scene following the merger activities of Air Berlin in the past few years and although germanwings has stabilised its fleet (and, unlike many other LCCs in Europe, cut capacity by 6% this year) it has carried 8% fewer passengers in the nine months to September and seen load factors drop by nearly two points.

Austrian has been a partner of Lufthansa since 2000 in the Star alliance and helpfully, like SWISS, almost speaks the same language. The company finally gave up ideas of independence and effectively invited Lufthansa to rescue it late last year: the Austrian government pumped in €500m in state aid and after handing over the ÖIAG stake and a public offer practically gave the former flag carrier to LH for nothing. There may not quite be as much synergistic benefit to come as there was from SWISS: the two companies have been operating a joint venture on all routes between Germany and Austria for the past nine years and have already been gaining some reasonable revenue benefits from cross–scheduling through their respective hubs.

However, they had also been competing against each other (from LH’s case through Munich, which is only 240km away from Vienna) in what Austrian has come to see as its core niche market into central and eastern Europe. Vienna, however, does present an impressively efficient hub and has an added advantage of being the easternmost European hub, allowing some of the most efficient timings of flights to and from the Middle East. Having restructured its long–haul network in the past few years Austrian has become increasingly dependent on short–haul transfer operations: the “Focus East” strategy effectively generating niche premium feeds through Vienna but on relatively low density routes into the CEE states that others cannot afford to reach. At the same time, however, the company has been particularly badly hit by the incursion of LCCs into the Vienna market.

The bmi problem

The two companies nevertheless appear to anticipate being able to generate some €80m in annual synergies. Apart from these, Austrian has introduced a new strategy (“Austrian Next Generation”): focus on volume routes but continue to serve niche markets; strengthen the position of Vienna as the Lufthansa group hub focussing on CEE markets; remain a network carrier; lower unit costs by removing small capacity aircraft (the 50–seaters are to go) and increase the seating density on existing aircraft. bmi is a completely different matter – apart from anything else being far more expensive an acquisition while being half the size of Austrian.

Lufthansa started consolidating the company from the beginning of July and became sole shareholder from the beginning of November. bmi’s main (and possibly sole?) asset is its position as second–largest operator at Heathrow behind BA, with 11% of the slots: but as the second largest carrier its route network appears intrinsically unprofitable. It does, however, bring in an extra 9% in passenger numbers and capacity to the group total – with a heavy focus on Europe and to a lesser extent the Middle East and Africa. Lufthansa could attempt to combine the slot portfolio with some of its own 4% (and maybe link in with SAS and United) to give the Star alliance 21% of the operations at Europe’s main gateway – though it would still need to find a way to operate those slots profitably.

The group management clearly has not really decided what to do with the carrier it has acquired, and at the results' meeting in Frankfurt reiterated that it was examining all options. In the meantime it has appointed new top management: Wolfgang Prock–Schauer (formerly of Jet Airways, and before that Austrian) will take over from Nigel Turner as CEO (who is becoming deputy chairman) from December. They have already started slimming some short–haul European routes and the long–haul routes from Manchester, but this may be short–term window–dressing of the problems. easyJet’s withdrawal from East Midlands nevertheless gives bmibaby (its attempt at the LCC market) some breathing space at the company’s home base – even though it has just announced plans to cut the 17–strong fleet by five aircraft.

Management says that it expects to have a comprehensive restructuring plan in place for bmi by the end of November. The options clearly are not as straightforward as for either Austrian or SWISS: LHR with its significant constraints on capacity is not an easy place to run a network hub (and Lufthansa is a network carrier par excellence) and because of London’s geographical position within Europe it is therefore difficult to see any real revenue benefits accruing from greater control over network route allocation and marketing without eating in to Lufthansa’s own network. There should, however, be some further cost savings from joint station operation (Lufthansa itself has just moved into Terminal 1 at Heathrow), and the hub concept may improve as all the Star alliance members move into what will become Heathrow East. In the meantime it is likely that bmi will be a drain on Lufthansa’s results for quite some time. One option may still be to sell the company – if it can get a reasonable price – and at least Willie Walsh, British Airway’s CEO, the other day confirmed publicly that it would be in the market, and actually regarded some of bmi’s route network as attractive, whether it could afford it or not.

These are interesting times for the airline industry and Lufthansa’s management is obviously taking advantage of others' weak positions and the resulting opportunities to build a unique portfolio of brands, hubs and fleet. “Interesting times” sometimes do turn out to be a curse; but it may well be that the German flag carrier indeed has the right board structure to manage an even larger portfolio. At the analysts' meeting for the nine–month results, when asked if there were other acquisition targets under consideration the response came back that “there are acquisition targets out there that we can afford but wouldn’t want and those we would want but cannot afford ... but our priorities must be to be able to generate strong cash flow (to restore the balance sheet) and sustainable returns through the cycle”.

| Under | |||||||||||||||

| operating | |||||||||||||||

| LH | LX | LCAG | CLH | EN | OS | BD | EW | 4U | SN | XQ | Total | lease | Orders | Options | |

| A319/20/21 | 99 | 36 | 21 | 30 | 27 | 4 | 217 | 48 | 47 | ||||||

| A330 | 15 | 13 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 36 | 10 | 7 | |||||||

| A340 | 52 | 13 | 2 | 67 | 4 | ||||||||||

| A380 | 0 | 15 | 5 | ||||||||||||

| 737 | 63 | 11 | 17 | 11 | 17 | 119 | 17 | ||||||||

| 747 | 30 | 30 | 20 | 20 | |||||||||||

| 757 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| 767 | 6 | 6 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| 777 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| CS100 | 0 | 30 | 30 | ||||||||||||

| Embraer | 11 | 4 | 3 | 18 | 36 | 8 | 17 | 50 | |||||||

| Others | 38 | 20 | 19 | 72 | 14 | 56 | 27 | 26 | 272 | 53 | |||||

| Total | 308 | 86 | 19 | 72 | 14 | 104 | 68 | 27 | 27 | 45 | 20 | 790 | 142 | 136 | 105 |

Notes: SN and XQ not consolidated. Operating lease numbers exclude SN and XQ.