British Airways, A318s and the masters of the universe

November 2009

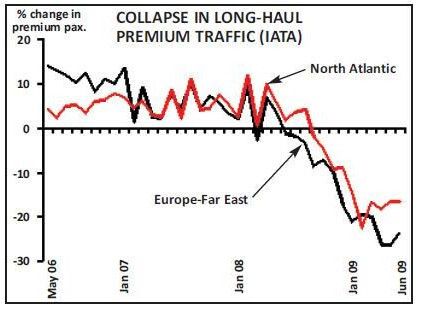

In an attempt to stem the collapse in premium long–haul traffic, British Airways has launched a remarkable new service from London City Airport (LCY) to New York JFK using A318s. It has been given the flight number 001, re–designated from the former Concorde operation. Might it work?

Aviation Economics looked at this concept a couple of years ago for a group of potential investors in an A318 LCY–based long–haul airline and came to the conclusion that the New York route looked very promising but that prospects for an independent airline operation (as opposed to an operation within a network carrier) were questionable.

BA is aiming at a niche market — the masters of the universe who inhabit the City of London/Canary Wharf and Wall Street. The attraction for London–based high–flyers is time and convenience. LCY is 15 minutes from the City, five minutes from Canary Wharf; it’s possible to get from curbside to departure lounge in less than 15 minutes. Flying from Heathrow, one has to allow more than two hours from the City and endure rush–hour crowds on the tube or risk London traffic in a taxi. Importantly, the A318 promises to create an elite club atmosphere – the aircraft are configured with only 32 flat–lie seats and are equipped with OnAir communications.

Technical issues

The A318’s unit operating economics (per seat–mile) on the North Atlantic are more than three times those on a 777, but average yields will hopefully be more than three times greater. BA is currently selling at around £2,600 one way, identical to its business–class fares on LHR–JFK. In reality the average fare achieved will be significantly lower than this, as all of the big financial institutions have loyalty deals with BA that discount published business class fares. Even after taking the discounted average fare into consideration (say 25% on average off published rates), break–even on the route with load factors in the low 60%s (i.e. around 20 passengers per flight) looks feasible. There are a couple of technical issues — the A318 cannot make the westbound trip non–stop because of a combination of weight take–off limitations at LCY and Atlantic weather conditions. The refuelling stop at Shannon is unavoidable, and gives the A318 a 1.5 hour elapsed time disadvantage over a LHR–JFK flight on this leg. But pre–US immigration and custom checks are being performed at Shannon, allowing passengers to be delivered directly into the JFK domestic terminal — and this is being turned into a selling point. Also London City airport is closed for 24 hours at the weekend as agreed with the local population, so scheduling is limited to five and a bit days per week — and if you want to arrive back in London on Saturday or early Sunday you can’t.

The timing of the product might seem odd. It was conceived when corporate travel was booming but launched into a regime of cut–back budgets and downgrading of travel privileges. On the other hand, recent profit announcements from the investment banks and a resurgence of interest in M&As suggests that the launch of this service might just be propitious. British Airways itself commented on an uptick in premium travel during its November 6th analyst meeting, and even suggested that the “Open Skies” 757 operation from New York to Paris Orly was showing promising signs.

Service limit

Launching the A318 service under the BA brand has clear advantages, compared with an independent start–up. Passengers add points to their BA frequent flyer programmes when using the A318 and they can visit existing executive lounges, but — more importantly — they have a fall–back if there is a technical event (as there was on one of the first A318 flights). Passengers can be transferred to a regular JFK–LHR operation, and of course will have to be compensated, but the costs involved are nowhere near the amounts that MaxJet and SilverJet incurred when they had to transfer passengers to other carriers (mainly Virgin Atlantic) when they, for whatever reason, couldn’t meet their schedules. BA can accept the limitations of this niche operation – it is possible to envisage an operation with six A318s and 25 weekly frequencies, taking about 5% of the premium London–New York traffic, but not much more. Other long–haul destinations from LCY are not promising: Washington is government- related travel with no City of London base; Chicago is too far and without the financial demographic; Moscow is a possibility but only low frequency; Dubai requires a stop and is heavily competed from LHR. For BA this is not an issue, but it is for an independent operator striving for economies of scale, and for an exit sale story. BA’s problem, however, is working out how much business it is simply cannibalising from its LHR–JFK operation.