Air France/KLM: Thinking about competitiveness through the cycle

November 2008

Back in 1993 the state–owned Air France had just suffered a crippling strike, was losing out to start–ups and the TGV in the domestic market, had a very poor perceived product quality, a balance sheet in tatters and was heading for annual losses of some FRF7.5bn. It seemed very ill–prepared for the full force of European deregulation and was viewed as the basket–case of the industry. In short, its very survival appeared in doubt.

Fifteen years on and how things have changed. The Air France/KLM group is now by some measures the largest airline grouping in Europe, firmly in a pole position among the three network legacy carriers. It has been at the forefront of industry consolidation, is profitable and — as we enter this current downturn — has a healthy balance sheet. Notwithstanding the current financial crisis, weakening economic environment, damaged consumer confidence and slowing air traffic demand, the group held its annual investor day in Paris in October: the last such meeting to be chaired as CEO by Jean- Cyril Spinetta, the prime architect of this remarkable turnaround.

Naturally these events are used to present and reiterate some of the group’s strategic thinking; and since it holds its investor day during a closed period (the September quarter results are due for publication later in November), few meaningful details can be disclosed about current profitability. The presentation from deputy CEO (and CEO designate) Pierre–Henri Gourgeon indeed continued in much the same vein as since privatisation nearly a decade ago; the numbers just get bigger and more impressive. There were nevertheless some important messages to be gleaned.

The Air France/KLM management has obviously been thinking for some time of the group’s competitive positioning through this next cycle; it has concentrated on increasing flexibility in its medium–term planning; it is willing to react decisively and proactively in changing market conditions; and it has built a prudent and risk–aware financial strategy.

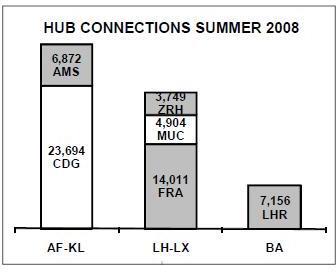

Air France/KLM has some pre–eminent competitive advantages. It has the largest international network of the three major European network carriers. The combined group operates to 114 long haul destinations, some 63% of the long haul points served by the AEA carriers, compared with BA serving 71 and Lufthansa (plus SWISS) operating to 85. Of these routes 42 (or 37%) are not served by the other two network majors — what the AF management refers to as "unique" routes — whereas both BA and LH/LX enjoy a greater overlap on the same measure — only 25% and 13% of their respective route portfolios offer "unique" destinations. Second, the twin hub system of Roissy CDG and Schiphol — each with their multiple parallel runways — provide the capacity to allow the group to run effective multi–wave network systems at their base airports, with little in the way of the capacity constraints and slot scarcity suffered by BA at Heathrow or LH at Frankfurt. This provides them with by far the largest number of connection opportunities through their hubs (short–haul to long–haul) of any of the network carriers. This last summer AF could market some 24,000 weekly transfer connections through CDG compared with 14,000 for Lufthansa at FRA and 7,000 for BA at LHR. On a group wide basis, KLM added some 6,900 to provide a total approaching 31,000, far outstripping provision by LH and LX at FRA, MUC and ZRH of 21,000 and dwarfing BA’s offering (see chart, left). The mere potential is not enough of course, but CDG is the only other airport destination after Heathrow that provides a good level of point–to–point demand to underpin a successful hub operation. This competitive position has been producing rewards — helped to no small extent by increased marketing of multi–hub routings — in that premium connecting traffic revenues grew by some 4% in the first half of this year, more than twice the rate of growth in point to- point revenues.

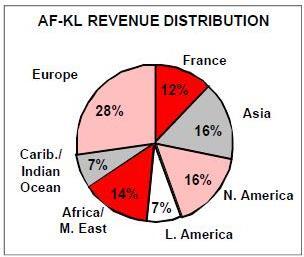

Third, the group has a relatively well–balanced network in terms of markets, traffic and revenues. Admittedly 12% of revenues arise from the domestic French operations (see chart, right) and a further 27% from intra–European routes (with 20% being point–to–point and subject to LCC incursion) but Asia and North America each account for 16% of revenues while the Middle East and Africa (with great help from francophone Africa since the demise of the Swissair empire) account for 14%.The Caribbean and Indian Ocean (albeit mostly leisure routes, these provide strong unique benefits, specifically the DomTom routes for AF and the Dutch Antilles for KLM) and Latin America supply a modest 7% each.

The KLM Joint Venture

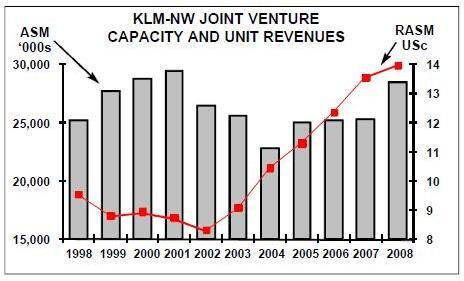

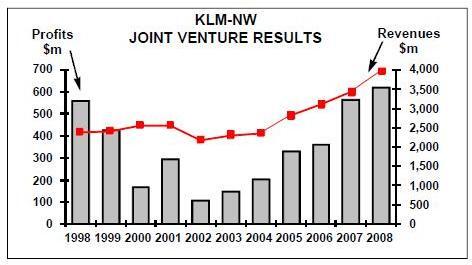

The fourth major benefit it sees is the (currently) unique four–way joint venture on the Atlantic between AF, Delta, Northwest and KLM. With Delta and Northwest likely to finalise their merger before the year end, the four have received full anti–trust immunity and originally planned to introduce a full cost, revenue, capacity and margin–sharing joint venture on the Atlantic in April 2010. This target they have now brought forward and aim to introduce the joint venture in time for the 2009 summer season. This will generate a business pooling of all the respective carriers' transatlantic operations (and some beyond routes) significantly widening the scope of the successful and long–standing KLM–Northwest joint venture to generate a business area with annual revenues of over $25bn. This will give them a pre–eminent market presence on one half of the Atlantic market — the bit that bypasses Heathrow — while they may no doubt be suffering a feeling of envy (or should it be schadenfreude) at Lufthansa’s success at gaining entry to Europe’s main transatlantic gateway. One of the more interesting presentations at the meeting was one from Leo van Wijk, former CEO of KLM, on the subject of joint ventures. KLM was the pioneer. Having taken a stake in Northwest in 1992 (and later forced to divest — at a profit though, which is unusual for an airline’s investment in a US carrier) it created a transatlantic joint venture with the Minneapolis–based carrier in 1997. It has naturally gone through various changes over time as they have ironed out the best ways of managing the structure, and has evolved into an almost irreversible linkage — the initial 10 year agreement was extended last year. Following the Delta/Northwest merger it will no doubt form the basis of the new AF–DL–KL–NW joint operation. The deal is effectively a margin–sharing agreement, with a pooling of capacity, joint pricing (thanks to ATI) and joint revenue management system. In one sense this type of JV on the Atlantic is a surrogate for that full merger forbidden by the ownership restrictions implicit under the Chicago Convention — and almost goes as far as a full merger would go to create the operational and capital advantages that would otherwise be available. The JV is based on the assumption that both carriers have fully aligned their interests so that neither worried nor cared which operated what route — save that naturally there is a clause in union negotiations to specify that there is a "fair" distribution of flying between the two. Given that both carriers operate from equally weak intercontinental hubs the benefits have been enormous. With a fully co–ordinated flying schedule, the JV created an exponential expansion in city pairs that they can (jointly) market through their respective hubs far beyond the conventional code–share agreement, giving many more markets and frequencies and improved asset utilisation.

Each has been able to cut out the waste of resources in the other’s home market — cutting out the individual sales organisations (always expensive at the other end of a route) and using the most efficient handling operations at delegated hubs and spokes per continent. Equally they have been able to achieve an efficient use of capacity for marginal network expansion: using a NW 757 for a route from Hartfield, CT to Amsterdam (a route KLM would never be able to operate on its own) or utilising NW’s route rights to India, via Amsterdam, (which also NW would never have been to operate profitably on its own) to provide KLM access to the sub–continent where it was restricted by the bilateral.

Strong finances

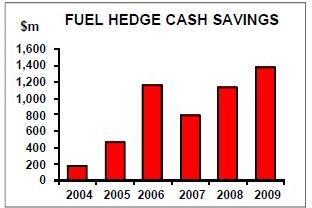

The returns appear to have been very strong: in the eleven years of joint operations (albeit with the downturn post September 11 and SARS providing a disruption) joint capacity has grown by 13%, revenues by 65% to $4bn and operating margins are exceedingly strong. Apparently Air France management was somewhat surprised to find, after the merger with KLM, that unit revenues being achieved by the JV on the Atlantic were several points higher than its own (and CDG with its natural O&D demand should be a far less revenue–dilutive hub operation than AMS) and the margins were impressively better (although in the past two years no doubt helped by the post Chapter 11 restructuring at NW): for the year ended March 2008 they appear to have achieved returns of $620m (a 16% margin) on $4bn of revenues. The group’s hope is no doubt that these returns will be achievable on the expanded agreement including Delta and Air France. On the finance side meanwhile, the group is in one the best positions it has ever been in during the approach to a cyclical downturn. This is partly due to what appears to be an excellent management of risk; throughout the increase in fuel prices in the past few years the group has operated one of the best fuel hedging strategies on this side of the Atlantic. Since 2003 it has achieved cash savings through its hedging programme of some $5bn from what it would have paid at spot prices — including a possible cash saving in this current year alone of $1.4bn. After the recent slump in the crude price of oil it still has reasonably effective hedges in place with a near 70% cover for FY2010 at an average $78/bbl equivalent, which would still provide it with cash savings at current forward rates of some €100m — and it will no doubt continue to build its cover at advantageous rates. Of course the hedging advantage will unwind and the group’s total fuel bill is still likely to continue to rise into a period where it may be increasingly difficult to get the passenger to pay — but these savings have significantly bolstered the balance sheet. It is certainly a sign of the times that the CFO felt it necessary to include a slide in his presentation showing details of how the group manages counterparty risk — through a "Proactive Risk Management Committee" — with strict group–wide limits on exposure to individual counterparties and daily monitoring of exposure. It is fortunate that, unlike Lufthansa, it had no exposure to Lehmans.

The balance sheet is in good health. Capital spending has been restrained in the past few years — ironically helped in part by the delays in the A380 delivery programme — while cash flow has remained strong. Net debt has fallen from €3.8bn at the end of March 2007 to €2.17bn at the end of June 2008 (representing a modest 24% of shareholders' funds down from 48% two years ago). The group currently has cash balance of €5.15bn (having drawn down €500m from a revolving credit facility in October as a "precautionary measure") and has a further €2bn available credit lines carefully spread through a plethora of banks. It is comfortable in maintaining (and exceeding) a cash/liquidity objective of 10–15% of revenues. Debt repayments over the next few years meanwhile are well spread with no real peaks: averaging €670m–700m a year. At the same time the underlying group debt is conservatively financed: of the €7.6bn total long term debt, 80% is secured on aircraft assets and 75% on fixed or swapped rates — and the advantage of secured debt is that it is still (just about) available and at reasonable rates.

The changing operating environment

Air France/KLM has one additional major competitive advantage — hardly really noticed by the markets or regulators — in that it has no pension funding problems (at least at the moment). For Air France, its French employees are all fully covered by the French national scheme; whereas at KLM its employees' pension funds are still (possibly even after the recent market slump) in surplus — and this is also after the group was able to recognise the negative goodwill that these funds provided on the acquisition of KLM in 2004. Earlier in the year AF/KLM was one of the first to adjust medium–term capacity plans to the changing environment. At the time of course the main threat was seen to come from the significant strength in the fuel price — which generated the requirement to raise prices and unit revenues to such an extent that it could destabilise demand. Since then events have changed and with the intensification of the financial crisis the world’s economies are palpably weakening towards a full–blown recession and business and consumer demand appears to be evaporating. The winter season for northern hemisphere carriers is naturally the weakest and the group has taken further snips out of its capacity plans — even after the start of the season. Originally targeting a 4% growth this season, AF/KLM has cut this to a 1.7% increase in seat kilometres — including a 1.5% reduction in short–medium haul operations and on routes to the Middle East. It has halved its plans for routes to North America (now +4.6%), Latin America (+2.8%) and Asia (+3%) while switching more capacity onto its routes in Africa. In reducing its capacity in the medium term it is helped by its relatively conservative fleet financing strategy — maintaining a third of its fleet on operating lease gives it the option to return equipment to lessors on a rolling basis. The group’s current plans see a 17% increase in the number of seats on long haul operations and a 6% growth on short haul by summer 2013. In a worst case scenario, the group could cut capacity by 12% and 17% respectively over the same period.

At the same time AF/KLM is in the process of reviewing its capital spending programme — helped in part by the delays in the A380 deliveries, but also apparently in negotiation with the manufacturers to delay or postpone some deliveries. The company presented its initial review projecting capex of €1.2bn and €1.6bn in FY09 and FY10 respectively down from €1.4bn and €2.1bn. In the absence of Armageddon these should still sit comfortably within cash flow generation. As this action will defer the spend into following years, it looks as if there would still be a jump in capex in FY11 to €2.1bn.

Meanwhile the group has one final, additional advantage — the extraction of further synergies from the 2004 merger with KLM. Initially it appeared that most of the benefits of the acquisition were merely coming from incremental revenue gains — but then, cynics would say, in a sense revenue gains are simpler to achieve when you cut out a competitor. Last year the group introduced a "Challenge 10" cost reduction programme to target an additional €1.6bn of profit enhancement by March 2010; of this they had targeted a run rate of €430m by the end of the current financial year. It recently expanded its expectation for the current year savings to €620m (some 20% of which comes from early retirement of older equipment) — and in light of the current economic environment, the management announced that it has started to develop a "Challenge 12" programme to prolong and deepen the integration of the two companies. The initial idea seems to be to try to double the savings and generate an additional €1.2bn of operating synergies by 2014.

Although the management was unable to comment too much on current profitability, it did accept that it was unlikely to reach earlier targets for €1bn in operating profits this year — which the markets interpreted as a profits warning. Given the dire economic background there will no doubt be great difficulty in achieving reasonable levels of returns for some time. In the interim, Air France/KLM, with the levels of operational flexibility it has introduced and with the strength of its balance sheet, appears far better placed to survive and emerge far stronger from this downturn than many competitors.