British Airways - coherent strategy, tactical frustrations

November 1998

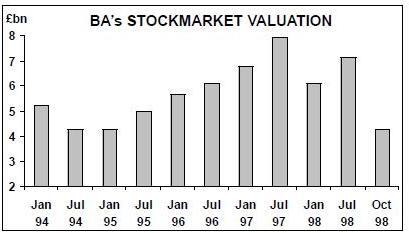

More than any other European airline stock, British Airways has been hit by an apparent collapse in investor confidence. As at the end of October its share price was down about 45% (relative to the FT all–share index) compared with 12 months ago. Has something gone fundamentally wrong with BA’s strategy, or is the stock–market overreacting to tactical setbacks?

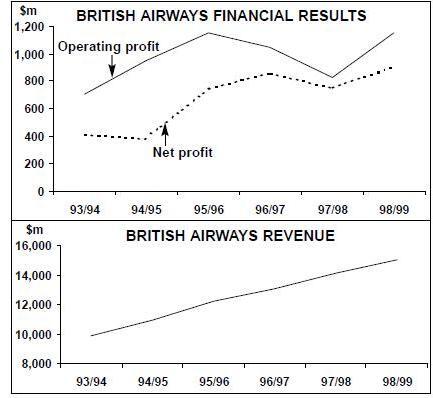

Although BA’s first quarter results covering the three months up to June 30th 1998 showed a headline pre–tax profit figure of £145m ($237m), which was in line with analysts’ forecasts, the make–up of the headline number was not as expected. Of particular concern was the 4.3% decline in passenger yields, caused by a combination of the strength of sterling and, more worryingly, a slowdown in the growth of premium traffic.

This has meant that further emphasis is being placed on BA’s ability to deliver on its business efficiency programme. While pre–tax profits have, since 1995/96, ranged between £580m-£642m ($950m-$1,052m) — and are forecast by Goldman Sachs to be £616m ($1,009m) — in 1998/99, these figures have been achieved against annual cost savings of £250m ($410m). Thus BA will have generated £1bn in savings by the year 2000 — but at no likely improvement to the bottom line. There is a growing concern amongst investors as to what effect these continued cost savings will have both on customer service levels and staff morale.

Strategically, BA was probably correct in attacking labour costs in 1997 when the market was strong and there was no hint of recession (and well before its competitors). Tactically though, the cabin unions were clumsily handled, the strike was acrimonious and labour relations are still at a fairly low ebb.

Pilots in particular are rumoured to be spoiling for a fight, concerned over continued outsourcing through franchisees and BA’s so–called virtual airline arm Airline Management (AML). AML was set up by BA with Gatwick–based Flying Colours to operate low–yield, long–haul scheduled services from Gatwick, primarily to the Caribbean.

The limits of BA’s outsourcing policy may now be being reached. Easy spin–offs like catering and engine maintenance have been sold. Airframe overhaul is now under pressure from management to meet more exacting targets in terms of productivity, on–time performance and greater reliability. Failure to achieve these targets may result in BA looking at outsourcing options, but the risk is more friction with the unions and potential disruption to its operations.

Fleet planning

After six months of speculation, BA finally opted in August for up to 188 A320/319s, although only 59 of them are firm orders, rejecting 737NGs from its traditional supplier Boeing and buying from Airbus for the first time. While political considerations may have played a peripheral role (with BA wanting to present itself to the Commission as pro–European as possible), achieving the lowest possible procurement costs was, as always, the highest priority.

BA asked the banks to liaise with the manufacturers and to come up with a form of funding for the order which would provide BA with maximum flexibility and be structured in such a way that BA would not have to show the aircraft on its own balance sheet. It was looking not just for an operating lease, but also for a ‘power–by–the–hour’ arrangement. Disappointingly for BA, no effective proposal was made and the airline reverted to standard financing techniques. However, this was a strong indication that BA continues to think deeply about purchasing capacity from third–party suppliers despite its ability to negotiate unit prices that (although unrevealed) were undoubtedly very low — in other words, the virtual airline concept.

At the same time, BA ordered up to 32 777- 200s and further emphasised its commitment to downsized widebodies by cancelling an order for five 747–400s.

The key idea behind downsizing is that operating costs per seat will be about 20% lower on a 777 than on a 747–100/200, while average yield will be boosted because BA will maintain the same first/business class configuration in the smaller jet as in the 747 — in effect discarding economy seats. Over the next 10 years Boeings should be the only type in BA’s long–haul fleet, though BA still manages to keep the pressure on by reiterating its interest in the super–jumbo and in particular the A3XX.

In the near future the only BA aircraft operating out of Heathrow will be Boeings. The plan is to maximise the value of its slots by not operating aircraft smaller than the 757 from that airport. The A320 family will be deployed from Gatwick, Birmingham and Manchester and by BA’s European subsidiaries in France and Germany. However, the fleet plans of Go at Stansted are still based on 737s, with another eight to be delivered over the next 18 months from GECAS in order to expand the existing five–strong fleet.

BA/AA unconsummated

BA’s failure to consummate its alliance with American — “an alliance made in heaven”, according to Bob Ayling — has been reported endlessly over the past three years. BA gives the impression that it feels that it has been unfairly singled out by the EC — subjected to scrutiny that KLM or Lufthansa avoided — and that the EC has failed to address wider competition issues (such as Lufthansa’s control of 95% of the intra–German market at Frankfurt). “Too much regulation, not enough vision”, as Bob Ayling puts it.

Yet the tedious EC process has not been helped by BA’s less than cordial relations with Karel van Miert, the competition commissioner. First of all, BA misread the EC’s powers to intervene in a UK–US alliance, then it managed to offend the commissioner — who is very protective of his staff — by describing his department’s research as “shoddy”.

In recent weeks BA seems to have moved to the position of going ahead with the American alliance without anti–trust immunity, which is how the other transatlantic alliances started. In the current economic climate, with downturns or even recessions looming on both sides of the Atlantic, this may make a lot of sense. In the short–term BA would not be obliged to give up Heathrow slots, and direct transatlantic competition to/from this hub would remain limited to itself, its semi–ally American, United and Virgin. The prospect of Continental, Northwest, Delta, TWA and even British Midland gaining transatlantic slots at Heathrow cannot be attractive to an airline that earns 54% of its operating profit on these routes.

Moreover, it has become obvious that BA is not getting anywhere with its argument that it should be allowed to sell the 267 Heathrow slots that the EC is demanding it relinquishes. Even if the UK department of trade and industry gives its approval for the slot sales, the Commission remains implacably opposed to the concept and would certainly attempt to block any monetary transactions.

The breakdown of the US–UK bilateral talks has added a further complication. The US delegation walked out in mid–October, complaining that the British appeared uninterested in an open skies agreement. The walk–out is a fairly standard negotiating ploy, but BA must be concerned by reports emanating from Washington that the DoT would not approve even a limited, non–immunised BA/AA code–share agreement in the absence of open skies and increased access to Heathrow. Then the two airlines would be forced to argue their case against the DoT in court, with yet more delays.

The oneworld brand

The launch of oneworld was muted and received a mixed press coverage. BA and American would certainly have preferred to have been able to announce more at the launch but, of course, were unable to do so because of the uncertainties of their core alliance. At the same time something had to be done to counter Star’s progress.

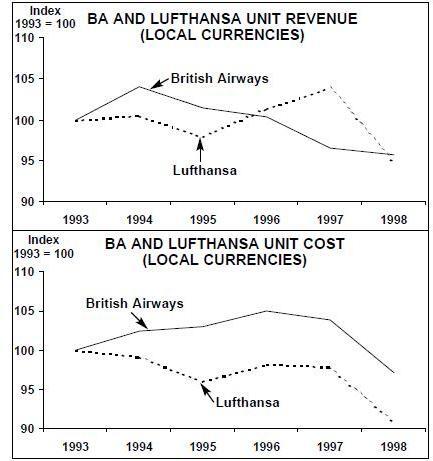

Star is now two to three years ahead of oneworld, with a brand image that is now widely recognised — and is set to extend this lead. More importantly, Lufthansa and United have started to steal traffic — particularly premium traffic — away from BA. The scale of traffic steal is almost impossible to measure, although BA executives are certain that it is taking place. Sterling’s strength relative to the Deutschemark has also undermined BA’s traditional competitive advantage over Lufthansa.

Although BA’s net profits and operating cashflow are still significantly above Lufthansa’s, the gaps are closing. According to Goldman Sachs’ forecast, BA should increase its net profit by $191m between 1997/98 and 1998/99 and its operating cashflow by $340m, but the equivalent figures for Lufthansa in 1998 and 1999 are $311m and $440m.

Whereas the Star alliance is being built up as a partnership, organised around a growing number of committees, oneworld is likely to evolve in a rather different manner, as BA and American are dominators, not co–operators. Already there are signs of tension.

Cathay is a reluctant partner, almost forced into joining as a consequence of the Asian crisis and by the indications that SIA will join Star in the near future. There are synergistic benefits especially if Cathay finalises its purchase of 40% of PAL (see pages 6–8). Cathay is treading very carefully and may be dubious about co–operating with traditional arch–rival Qantas. Canadian has experienced the downside of being a junior partner when its part–owner American forced it to hand over a large proportion of its transborder operations.

The next stage of oneworld’s development is to expand beyond its anglophone core. JAL is certain to be co–opted next year, providing the alliance with a key link in northeast Asia and counterbalancing the Star/ANA axis. Less obviously, Swissair could now be considered as a potential oneworld member — its attraction lies not only in the revenue benefits that could be generated but also in its role as a supplier of other services to oneworld through its fellow group members, Nuance, Swissport and Gate Gourmet.

Then there is the question of the colourful tailfins. BA made a brave attempt to globalise its brand by replacing the British flag with world art, but it is still taking flak from several quarters. Versions of the new tail–fin have been applied to Air Liberte aircraft in France and Comair jets in South Africa, but are the other members of oneworld expected to follow suit at some point?

Bob Ayling recently stated that he fundamentally regards alliances as a compromise forced upon the participants by archaic laws on national ownership — "If we could merge, we would merge", he said. So the probable long–term vision for oneworld, when ownership rules are abandoned, is that BA and American (and possibly JAL) will indeed merge into a true multinational, along the lines of Unilever, BAT or Shell. Airlines like Qantas and Canadian may well end up being 100% owned, while minority stakes will be sought in Cathay and others.

European strategy

That BA prefers to exert management control wherever possible is revealed in its purchase of controlling stakes in European carriers Air Liberte (which in turn is making a bid for AOM) and Deutsche BA. In recent years BA has scarcely broken even on its European services, but now it seems to be building a coherent strategy based partly on future A320 communality and hub strength.

With Air Liberte plus AOM, BA will have a powerful presence at Paris Orly. In addition, American — which also flies there — has just announced a code–sharing agreement with Air Liberte. BA’s lingering worry is that the French authorities will attempt to shift all intercontinental services from Orly to CDG — a plan that was floated by the transport ministry a few months ago.

BA has already experienced fierce resistance to its intra–European expansion. When Deutsche BA attempted to get into Frankfurt earlier this year it found that Lufthansa was determined to match its fares on Munich–Frankfurt, even if DBA went down to zero. Eventually DBA had to admit defeat.

When the regulatory regime is clarified, BA will have the possibility of using its continental European partners for long–haul services; for example, Air Liberte could operate transatlantic services from CDG. This would be a new and direct way of attacking the competing alliances.

BA’s current aim is to ensure that Lufthansa/Star does not enjoy a completely dominant position in its traditional northern and eastern European markets. Hence, its alliance with Finnair and the build–up of code–sharing operations at Stockholm (see Briefing, Aviation Strategy October 1988), its block–seat arrangement with LOT on Warsaw–Heathrow and its possible interest in code–sharing with Malev.

BA has been willing to take the unusual step (for it) of buying a small stake — 5% — in Iberia, which will not convey any management control. This is in effect its entry ticket into the Spanish/Latin American market and is part of a global play whereby American will also invest in Iberia and in Aerolineas Argentinas in return for an immunised alliance with Aerolineas. It will be interesting to see if this investment materialises, given the delays American is encountering in completing the Argentinian deal, the BA/American regulatory impasse and also the uncertainty over the date of Iberia’s privatisation.

Airport policy

BA, frustrated by the length of time the Terminal Five is taking and concerned by the rapid development of Paris (CDG will have 50% more runway capacity than LHR by 2000), complains noisily about the airport constraints it faces. It needs T5 if it is going to ensure that its promises of seamless service are met. Currently BA operates from T1 and T4, American is at T3 as is JAL, Iberia and Malev are based at T2 while Finnair is back at T1.

But BA has been able to implement an effective airport system strategy.

It has moved significant number of mainly longhaul routes to Gatwick from Heathrow in the past few years, including low–yield, tourist–orientated routes to the Caribbean and high–yield routes to Africa and Latin America where the regulatory regimes limit the amount of competition. Gatwick is now a very effective hub and has finally moved into profit some seven years after BA bought out the bankrupt Dan–Air.

At Gatwick BA has made heavy use of franchisees, notably CityFlyer and GB Airways, on thin and/or short–haul routes. And now there is speculation that BA is going to move more European flights to Stansted to be operated by Go. But such a move probably wouldn’t be implemented until the question of the BA/AA alliance and the slot give–ups is finally resolved. Then BA can expect union confrontation plus more regulatory problems as the Commission will listen very favourably to the independent low–cost carriers' complaints of unfair subsidisation of Go by its parent.

| Current fleet | Order(options) | Delivery/retirement schedule/notes | |

| 737-200 | 23 | 0 | To be replaced by A320 family |

| 737-300 | 7 | 0 | To be replaced by A320 family |

| 737-400 | 34 | 0 | To be replaced by A320 family |

| 747-100 | 14 | 0 | To be replaced by 777s |

| 747-200 | 16 | 0 | To be replaced by 777s |

| 747-400 | 48 | 9 | 5 in 1999, 4 in 2000 |

| 757-200 | 50 | 0 | |

| 767-300EREM | 28 | 0 | |

| 777-200/200ER | 19 | 20 (16) | For delivery in 2000-2002 |

| DC-10-30 | 7 | 0 | |

| A319 | 0 | 39 | Delivery in 1999-2004 |

| A320 | 10 | 20 (129) | Delivery in 1999-2004. Options are |

| for A320 family | |||

| Concorde | 7 | 0 | |

| TOTAL | 263 | 88 (145) |