United and the spirit of employee-ownership

November 1998

Since its July 1994 ESOP, United Airlines has become one of the most profitable US carriers, but is clearly struggling in its efforts to improve on–time performance and balance the need to reward employees and remain competitive. Who will take on the nation’s toughest airline CEO job when Gerry Greenwald retires next year? The company has managed the Asian crisis well but now faces uncertainties in Latin America. And what are the prospects for the Star alliance and the link–up with Delta?

United ensured a place in the history books when in July 1994 it became the largest company in the US to be majority–owned by employees. The ESOP deal gave workers an initial 55% equity stake, no–furlough and other protections, two board seats and veto powers over major decisions, in exchange for $5.2bn worth of concessions over 12 years.

The unions also got the right to choose chairman/ CEO Stephen Wolf’s replacement, and they picked former Chrysler vice–chairman Gerry Greenwald. And, significantly, they agreed to the setting up of a low–cost airline subsidiary, Shuttle by United, which was launched in October 1994 in major West coast markets as a first–ever direct challenge to Southwest.

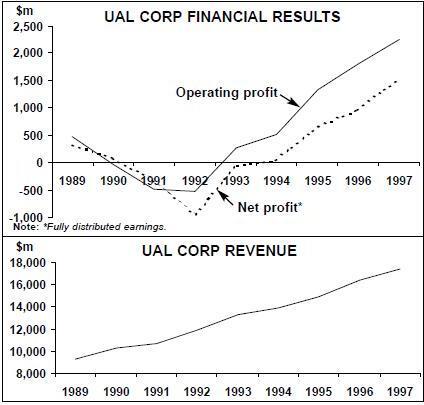

The deal was among the first employee buyouts for a relatively healthy company. Although United’s parent UAL Corp had lost $332m in 1991 and $957m in 1992, this was nothing compared to competitors’ troubles, and UAL’s net loss had already narrowed to $50m in 1993. But the management was concerned about losses on short domestic routes and had already deferred aircraft deliveries and announced plans for lay–offs and asset sales.

Not surprisingly, the ESOP deal was met with more scepticism than enthusiasm on Wall Street. There were doubts about the Shuttle’s ability to achieve a competitive cost structure and concerns about the extent of opposition to the deal among workers, the relative inexperience of the new leadership, the powers wielded by unions, potential conflicts of interest in corporate governance, the numerous restrictions that reduced management flexibility and the highly detrimental impact of the deal on the company’s balance sheet. Four years on, is United better or worse off for the experience?

The Shuttle never got its costs anywhere near Southwest’s levels and ended up retreating from many competitive markets in 1996. Its fleet size is barely half of the 130 aircraft it was envisaged to operate after five years. However, it is profitable, has helped United retain a strong presence in California and has proved valuable in feeding high–yield traffic to United’s long–haul services from San Francisco and Los Angeles. It also spawned an important industry innovation — e–ticketing — which United has since also pioneered in international markets.

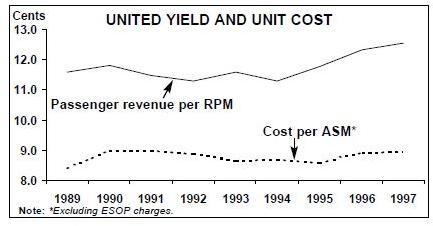

Despite the early–1995 move to the expensive Denver (DIA) airport, United has kept its unit costs below the 9–cent mark. Its costs per ASM, excluding ESOP charges, of 8.94 cents in 1997 were below American’s and Continental’s and only slightly higher than Delta’s. At the same time, United has consistently outperformed the industry on yield improvement: from 11.31 cents per RPM in 1994 to 12.55 cents in 1997 (see chart, page 12).

The initial fears that an employee–owned United would go on a hiring and aircraft ordering binge proved unfounded, though the company has grown faster than the industry average. Over the past three years, ASMs have increased by 3- 4% annually — more than matched by traffic growth. After an initial 6.6% cut in 1994, staff numbers rose from 76,100 to 91,700 in the three years to the end of 1997. In the same period, fleet size increased from 543 to 575 aircraft.

Labour cost savings and the Shuttle must have contributed to UAL’s financial turnaround and return to strong profitability. A marginal net profit of $51m in 1994 was followed by a $662m net profit in 1995, $960m in 1996 and $1,546m in 1997. Last year’s net profit margin of 8.9% was the highest among the major carriers (even beating Southwest’s 8.3%).

The recapitalisation associated with the ESOP deal significantly weakened the company’s balance sheet. Because of its fleet renewal programme, United has spent less than many of its competitors on retiring debt early, and consequently its long term debt and capital lease obligations were a substantial $4.26bn at the end of last year. This was about the same as in 1994, and debt has remained largely constant this year.

But the balance sheet has improved thanks to strong cash flow and equity boosts. Shareholders’ equity more than doubled last year from $1bn to $2.3bn. United has also gained investment- grade credit ratings, but heavy capital spending has meant that its ratings are not as strong as American’s or Southwest’s.

United has been repurchasing its stock for several years, but a formal programme was put in place only a year ago. Some 2.88m shares were bought back at a total cost of $250m in the fourth quarter of 1997 (when UAL also recorded $275m proceeds from the sale of Apollo Travel Services and a $103m gain on the sale of a subsidiary’s stock). A new stock repurchase programme of up to $500m was authorised in September 1998. The company has also started talking about paying dividends.

The sharp economic downturn in Asia — where United earns 20% of its revenues — in the early months of this year caught the carrier rather unprepared, but lower fuel prices, reduced capital spending and a quick reallocation of capacity in Asia rescued the situation. For the first quarter, UAL reported another record $218m net profit (up 1.4%), and in the June quarter its net earnings rose by 11% to a record $418m.

The company has just reported a $516m net profit (on a “fully–distributed” basis) for the quarter ended September 30, down from the year–earlier $734m or, if last year’s $235m after–tax gains are excluded, up from $499m. The third quarter was characterised by strong domestic demand (boosted by the Northwest strike), which more than offset weak unit revenues on the Pacific and increased industry capacity in the Latin American and transatlantic markets. UAL looks set to break earnings records for 1998. The current First Call consensus estimate is a net profit of $10.73 per share, up from $9.97 in 1997.

But UAL’s earnings, like those of most other major US carriers, are now expected to fall in 1999 — the current First Call estimate is $10.20 per share. The high level of debt and the long term job security provisions in the ESOP do not make United ideally prepared for an economic downturn, but the company believes that its flexible fleet plan and measures like a hiring freeze will enable it to stay profitable.

The ESOP deal has not lived up to expectations in terms of improving morale or leading to more cohesive labour–management relations. Flight attendants never joined the ESOP, and simmering resentment among other employee groups about the terms of the agreement has led to further unionisation. However, worker involvement has improved and, despite disagreements, United has not had any work stoppages or disruptions.

Nor has the ‘spirit’ of employee–ownership improved the carrier’s lack–lustre passenger service. United has persistently ranked near the bottom in the DoT’s on–time performance and other customer service comparisons.

But the power wielded by unions at United was amply illustrated by the mid–September resignation of UAL’s president and COO, John Edwardson. He stepped down when it became clear that the heads of IAM and ALPA would not support him to succeed Greenwald as chairman and CEO, even though he had the general support of the board. Greenwald is expected to retire when his five–year contract expires in July next year.

Edwardson was instrumental in mending UAL’s balance sheet and managing the return to strong profitability. But the unions did not like his “bottom–line mentality”. UAL quickly named James Goodwin, its senior VP–North America, as Edwardson’s replacement, but he will not necessarily be the next CEO. There are no obvious candidates for the top post, which is likely to be a very hard sell.

Labour challenges

The biggest challenge facing the next CEO will be to secure new contracts with IAM and ALPA when their current agreements expire in 2000. The big question is: will the ESOP be extended?

Negotiations for the first interim wage adjustments for the pilots, mechanics and machinists last year suggested that the circumstances have changed. The deals had to be considerably sweetened over what had been envisaged in 1994. Contrary to the earlier ESOP provisions, the company also agreed to restore wage rates to the 1994 pre–concession levels in 2000.

In October 1997 United’s 22,000 flight attendants, who had earlier turned down a tentative agreement and threatened to strike, finally ratified a 10–year contract that guaranteed three 2% pay rises over five years and seven lump sum payments of 3–5% of annual wages over ten years. Further negotiations in 2001 could lead to additional increases in wages, per diem expenses and retirement benefits.

There is now a new employee group to negotiate with: the 19,000 passenger service and reservations agents who in July voted to be represented by IAM. This came about because of widespread resentment among non–union workers about the terms of their ESOP deal, in particular the new two–tier pay scale that penalises new workers.

The mid–term wage adjustments led to a substantial hike in United’s labour costs in 1997 and this year, though that has been masked by the decline in fuel prices. The AFA contract will cost at least an additional $1.2bn over ten years. But the plan is to try to offset the higher labour costs through savings from fleet streamlining, new technology and efficiency improvements.

The recent sharp decline in airline share prices will not have enhanced the popularity of the ESOP, though UAL’s shares are still trading at almost three times their value than when the ESOP went into effect. The next ESOP will no doubt incorporate changes, such as allowing nonunion employees to vote on the deal.

Quality and reliability issues

United has always been stronger on the network than product side, but the post–ESOP strategy has been to try to improve the latter through new recruitment in customer service, product upgrades and better training. The company is now also demanding higher standards from its commuter partners, which led to the termination of Mesa’s United Express contracts at Los Angeles and Denver.

The flagging on–time performance is now being tackled with “Start the Airline Right” (STAR) programme, which copies US Airways' successful efforts to focus on the first flights each morning, and various process changes recommended by employee task forces. United has blamed the delays partly on its complex hub–and–spoke system and the multitude of aircraft types used, and it is also exploring schedule changes and hub redesign.

Fleet plans

United’s post–1995 fleet strategy has focused on retiring older aircraft and replacing them with newer, more cost–efficient models. The long–term aim is to simplify the fleet from 10 to five types. Since the early part of this year, the strategy has also been to grow in order to take advantage of profitable opportunities. The latest plan reflects 3% annual growth in capacity and calls for the net addition of 68 aircraft over four years, from 571 at end of 1997 to 639 at the end of 2001.

United introduced the 777 in 1995 as that type’s launch customer. Initial reliability problems with the 777 led to a decision to order another batch of 747–400s the following year. A $3.5bn order for 27 Boeing widebodies (mostly 747- 400s) in August 1996, for delivery in 1997–2001, marked the start of the process to replace 17 747–100s, which had an average age of 24 years, and nine 747–200s. A $3bn order for 23 Boeing aircraft in April 1998 marked the start of the widebody fleet growth phase. Significantly, the bulk of the order (16) was for the 777–200, which will total 52 when all the aircraft have been delivered.

United has continued to build up its narrowbody Airbus fleet since introducing its first A320 in late 1993. This year’s two A319/A320 orders, for a total of 52 aircraft, marked the start of the narrowbody growth phase. The carrier is also hush–kitting 75 older 727s, which it can retire in the event of an economic downturn.

Domestic strategy

The Shuttle has succeeded in protecting United’s West coast markets because it offers low fares, full–service amenities and mainline FFP participation. It has given United a strong 30% market share at Los Angeles, compared with American’s and Delta’s 12% each, when only a few years ago the three had roughly equal shares. The “newest hub” has been strengthened with new long haul services and a $200m project is under way to renovate terminals and expand the Shuttle’s facilities by 40%.

United took the Shuttle to its Denver hub in early 1997, where it proved an effective weapon against low–cost new entrants like Frontier and WestPac (the latter filed for bankruptcy and ceased operations in February for unrelated reasons). The Shuttle’s network now includes nine cities in California and 12 in seven other Western states. Last year it accounted for 11% of United’s total flying hours and 16% of passengers.

The past year has seen extensive restructuring of feeder operations in the West. A new high–quality partner, SkyWest, has succeeded Mesa and Westair as the United Express operator along the West coast, and feeder services there have been substantially expanded. Mesa’s Denver operations were awarded to existing partners Air Wisconsin and Great Lakes Aviation.

United has continued to expand its substantial transcontinental network with the help of new A319/A320s, which have the coast–to–coast range and the smaller size (the A319) to make new or thinner markets viable. They have been used to launch new services such as Washington Dulles to Portland and San Jose, Baltimore to Los Angeles and San Francisco, Boston to San Jose and San Diego, Hartford to San Francisco and Tampa to Los Angeles.

While domestic code–sharing plans with Delta are in limbo, United has just greatly expanded code–sharing with Air Canada to cover more than 600 United flights throughout its domestic system.

Asian troubles, European strength

Sharp intra–Asian service cuts in February, followed by the suspension of San Francisco- Seoul and Osaka–Seoul services in May, enabled United to limit the financial damage of the Asian crisis. A 13% Pacific traffic decline and lower yields reduced UAL’s pre–tax earnings by about $75m in the first quarter, but the Asia division broke even in the second quarter as a 12% capacity cut enabled load factors to be maintained.

United has managed the crisis fairly effectively by continuously reshuffling capacity within Asia to suit demand conditions. It has introduced a new Chicago–Hong Kong service, resumed Osaka–Seoul flights and restored Tokyo–Seoul frequencies. But it will now eliminate Honolulu- Osaka flights due to very low yields and heavy losses and transfer the aircraft to the San Francisco–Honolulu route. In December it will drop its daily Hong Kong–Singapore service and redeploy the capacity in the Hong Kong–Bangkok market.

The new US–Japan ASA has enabled United to substantially boost its services to Japan. Since April it has more than doubled its flights from Chicago to Tokyo, introduced a daily Chicago- Osaka summer service and re–entered the international market at Seattle with a new daily nonstop service to Tokyo. But the combined effect of the flood of new capacity on US–Japan routes and Japan’s worsening economic recession has been to keep yields under pressure. United’s smartest move in Asia, therefore, must be the marketing alliance forged with ANA.

The transatlantic market, which last year accounted for 10% of United’s revenues, has continued to perform well. This year has seen the addition of Munich and new frequencies to London Heathrow and Paris. In the event of a USUK open skies ASA, United would commence service to Heathrow from Boston, Denver, Miami and Seattle and increase flights to Heathrow from Newark, Washington DC, JFK, Los Angeles, Chicago and San Francisco.

Latin American uncertainty

Because of the smaller Majors’ aggressive expansion, United has lost its second position on US–Latin America routes to Continental and will soon be overtaken also by Delta. Its share of US carriers’ traffic on Latin America routes is now just 8%, compared with American’s 56%, Continental’s 19% and Delta’s 7%.

However, after a marginal decline in 1997, this year United has again been expanding to the region. Its Latin America capacity in September was 16.4% higher than a year earlier. While Miami continues to be the main gateway, much of the latest expansion has taken place from Chicago. United’s main hub has received new daily services to Sao Paulo, Guatemala City and Buenos Aires, while the Washington/Dulles hub has been linked with San Salvador.

The problem is that the significant overall Latin American capacity increase by US carriers this year has led to extremely low load factors on many routes. United ended the new Guatemala service after only five months and is now temporarily suspending its Lima–Santiago service for three months. Given that the economic prospects for Latin America now look uncertain, like other carriers United is waiting to see how the situation develops.

Codeshare alliances come particularly handy at times like this. After almost being left out of the Latin American alliances game, United secured the most prestigious of all partners, Varig, when the Brazilian carrier joined the Star alliance in October 1997. United has also continued to build on its successful commercial relationship with Mexicana.

Prospects for the Star alliance

Much of United’s international effort now focuses on the Star alliance. United estimates that Star and its other international alliances already give it $200m incremental revenues annually.

In addition to forging the Asian links, expanding code–sharing and introducing a joint FFP, over the past year the Star partners have focused on garnering cost efficiencies from the sharing of airport facilities, joint purchasing and managing of parts inventories and co–operation in cargo operations.

United is extremely disappointed that the proposals for Star and other alliances have been affected and delayed by the extensive BA/AA debate. It vehemently opposes the EC’s proposed conditions on Lufthansa/SAS/United, particularly since the EU countries concerned already have open skies ASAs with the US (the DoT is due to take action on United’s complaint against the EC by November 5).

While Delta and United began to link their FFPs on September 1, further discussions on domestic code–sharing were terminated after Delta’s board turned down its pilots’ request for a board seat — something that had been a precondition to pilot approval for the alliance. Motivation for domestic code–sharing has diminished also because of the difficulties and delays experienced by Northwest and Continental. But should the two carriers that started it all go ahead with code–sharing, United and Delta could probably quite easily revive their talks.

| Current fleet | Order(options) | Delivery/retirement schedule/notes | ||

| 727-200 | 77 | 0 | 75 being hushkitted | |

| 737-200 | 56 | 0 | ||

| 737-300 | 101 | 0 | ||

| 737-500 | 57 | 0 | ||

| 747-100 | 6 | 0 | To be replaced by 747-400s | |

| 747-200B | 9 | 0 | To be replaced by 747-400s | |

| 747-400 | 32 | 19 | For delivery by 2001 | |

| 747-SP | 3 | 0 | ||

| 757-200 | 86 | 2 | 1 in 1999, 1 in 1999 | |

| 757-200EM | 10 | 0 | ||

| 767-200 | 11 | 0 | ||

| 767-200EM | 8 | 0 | ||

| 767-300EREM | 24 | 13 | For delivery by 1999 | |

| 777-200 | 16 | 0 | ||

| 777-200ER | 18 | 18 (34) | 7 in 1999, 11 in 1999 | |

| DC-10-10 | 23 | 0 | ||

| DC-10-30 | 8 | 0 | ||

| A319 | 10 | 28 | For delivery by 2000 | |

| A320 | 46 | 27 (50) | For delivery by 2000 | |

| TOTAL | 601 | 107 (84) | ||