Austrian: Europe's ideal niche airline?

May 2003

Austrian Airlines Group (AAG) — comprising Austrian Airlines, Tyrolean Airways and Lauda Air — recorded impressive financial results in 2002 as its turnaround plan began to pay dividends. Has AAG cemented its place in Europe’s aviation industry as a niche carrier, or are there still potential challenges to its long–term viability?

Austrian Airlines is a relatively young European carrier, founded in 1957. It faced major problems in the early 1990s and racked up a substantial loss in 1993.

Yet under the management of joint presidents Herbert Bammer and Mario Rehulka, AAG gradually improved its performance through the 1990s based on three core strategies: cost–cutting, investing in potential domestic competitors and developing Vienna as an east–west hub (for more on AAG in the 1990s, see Aviation Strategy, August 1999).

At the end of the 1990s, the key challenge the group faced was deciding which global alliance to join following the collapse of its Atlantic Excellence alliance with Delta, Swissair and Sabena and the Qualiflyer alliance with Swissair and Sabena. AAG offered potential alliance suitors its Vienna hub — a major gateway between east and west Europe — but in truth AAG needed the insurance of being part of a global alliance far more than any alliance needed AAG. At the time there was plenty of speculation as to which grouping AAG would join, but in the end — and somewhat surprisingly, given that oneworld was seen by many as being the most likely link–up — AAG joined Star in March 2000. The benefit of joining such a global alliance has been immediate. Revenue from ticket sales by Star partners rose by 22% in 2002 to €280m, and AAG is aiming for around €470m in interline revenue by 2006.

September 11 …

Yet as soon as the future appeared relatively secure for AAG, along came September 11. As bad as this was for AAG, however, the group had already started running into weakening demand — from the second quarter of 2001 in fact. And with just 10.7% of AAG’s scheduled revenue coming from the North America segment in 2001 (falling to 8% in 2002), in actual fact AAG was far less exposed to the effects of September 11 than many of its European rivals.

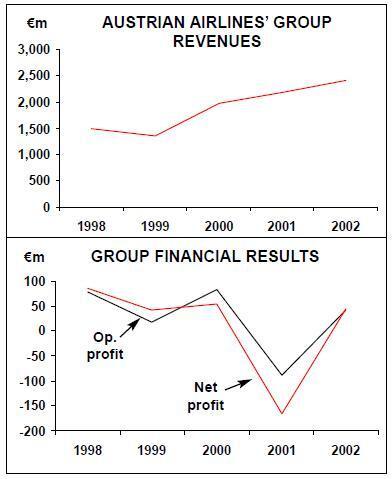

What September 11 did do was to reveal the underlying strategic vulnerability at AAG — vulnerability that existed despite all the good work done by Bammer and Rehulka in the 1990s. According to the company, September 11 "served to reveal the fundamental weakness of AAG: too high a cost base, yields too low in relation to these costs and a capacity utilisation below the industry average". A horrendous set of fourth quarter results led to an operating loss of €89m and a net loss of €165m in 2001 (see chart).

The substantial worsening of AAG’s position in 2001 led to the unexpected early departure of Bammer and Rehulka (they had previously planned to leave in June 2003), replaced in October 2001 by former SAS vice president Vagn Sorensen in the position of AAG CEO. Sorensen came to AAG with a slightly blemished past — he left SAS after the European Commission imposed a large fine following the airline’s involvement in an anticompetitive pact with Maersk Air.

Yet Sorensen’s appointment was an ideal opportunity to tackle problems afresh, and after a rapid assessment of AAG’s situation he set about implementing major changes at the end of 2001. Among the measures introduced were:

- A reduction in staff. AAG had 8,270 employees at August 2001, but by the end of 2002 this had been reduced by 1,000, largely achieved through voluntary redundancy and early retirement.

- A one–year agreement with unions to cut employee costs, including the suspension of a previously agreed salary increase, the implementation of a voluntary salary reduction and a cut in working hours. This reduced salary costs by a one–off €20m in 2002.

- A refocusing of group subsidiaries. Austrian Airlines now concentrates on scheduled operations, Lauda Air on charter services, and Tyrolean Airways (which now incorporates Rheintalflug, and which may be renamed Austrian Express) on regional routes.

- A reduction in aircraft capacity. AAG sold four aircraft in 2002, leased out six and took another six out of service.

- An overhaul of the route network. Now, long–haul destinations in Asia and North America are either substantial point–to–point destinations, niche destinations with little competition, or Star partners hubs (e.g.

Washington or Tokyo). Short- and mediumhaul routes are either profitable major routes to/from Austria or part of AAG’s east and central European network. AAG is aiming to become "market leader" on 12 of the 15 busiest routes to/from Austria, and is currently number one on seven of them.

- The setting of specific financial and operational goals on which AAG can measure improvement, such as an increase in the equity ratio from 13% to 30% by 2006 and a 10% reduction in unit costs by 2006 (unit costs have already fallen by 2.9% in 2002).

The restructuring appears to be working. AAG posted an EBIT of €41.4m and net profit of €43.2m in 2002, way above its own target of break–even on EBIT in 2002.

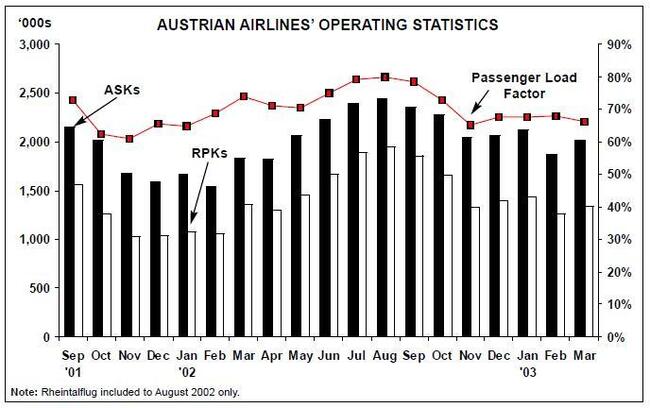

AAG’s scheduled RPKs actually fell by 4.7% in 2002 (due to cutbacks after September 11), but this was swamped by a 48% increase in charter’s RPKs so that overall RPKs increased by 6.3%. Scheduled capacity on long–haul has been eased back in favour of higher–yielding short- and mediumhaul routes, and that has fed through to the bottom line.

Sorensen has kept the restructuring pressure on following Gulf War II, with further cost trimming, closer co–operation within Star and greater fleet harmonisation.

The butterfly fleet

AAG’s fleet (see table, opposite) contains such a wide variety of types that some critics call it the Schmetterlingsammlung, or "butterfly collection". AAG has been attempting to rationalise for some time, and Lauda Air’s 777s have been the first type on the hit list.

Yet Lauda Air’s short–haul fleet is based on the 737 while over at Austrian Airlines the short–haul aircraft are mostly A320 family. To replace MD–80s Austrian Airlines has seven A319s on order, although originally these were A320 orders placed back in 1998.

The A320s were scheduled for delivery by mid- 2003 but the order was postponed due to September 11. In August 2003, AAG announced it was converting the order to smaller 126–seat A319s, which will start arriving in 2004, allowing the group to offer extra frequencies, but with smaller capacity, on selected routes. However, Tyrolean Airways still has a complete hotch–potch of aircraft that have yet to be sorted out, and the situation not helped by the addition of three ERJ–145s inherited in January 2003 when it absorbed regional carrier Rheintalflug.

In January 2003 an order for a 777 was converted to three 737–800s, but a measure of AAG’s cautiousness in terms of capacity is given by its estimate that the total fleet will grow to just 99 aircraft by 2006, compared with 95 today. AAG also intends to increase the flexibility of its capacity through greater use of operating leases.

First quarter 2003 financials are due to be released on May 6, although traffic statistics show that in January–March of 2003 total AAG ASKs were 18.6% up on the same period in 2002 (when capacity had been reduced after September 11) and RPKs 15.6% up, with a 1.7% drop in load factor to 67.2%. In reality, AAG has reduced ongoing capacity by 7% during January–April 2003 in response to Gulf War II, so a more telling measure given the circumstances is passengers carried, which fell 0.1% to 1.7m in the first quarter of 2003.

AAG had predicted net profits of €45m for 2003, but now says it will not meet that target due to events in the Middle East, even despite new 2003 measures such as a hiring freeze and reduction in investments. In early April AAG announced it was targeting another €60m cut in costs through 2003 in order to offset the effects of Gulf War II.

Four aircraft were temporarily grounded (15 were grounded after September 11), which AAG claims will account for a third of the target. Other measures include job cuts of around 150, although it is still in talks with unions about this, and there is a danger that AAG may be pushing the unions too far.

At the end of 2002 AAG served one year’s notice on Austrian Airlines' pilots that it was withdrawing Clause 33 — a guarantee that Austrian Airlines would operate at least 43% of AAG’s capacity. In addition AAG wants to substantially cut Austrian Airlines' pilot salaries, which are twice as high as pilots at the other two subsidiaries according to management.

Not surprisingly, Austrian Airlines' 500 pilots and 1,350 cabin attendants have not taken kindly to these moves, and in January 2003 they voted to take industrial action if current talks with management fail to resolve the matter.

A clash with unions in 2003 is not something that management (nor anyone else) wants, but this may be inevitable given that AAG wants to concentrate capacity growth at the lower cost Lauda Air and Tyrolean Airways.

Competitive threats

But union unrest is not the greatest danger facing AAG. That honour goes to the increasing threats to AAG’s only — and therefore critical — strategic advantages in Europe: its grip on the Austrian market and its Vienna hub, built up as an east/west Europe gateway.

Ironically, these threats came about thanks to AAG itself. In July 2002 the European Commission ruled that as a condition of its approval of AAG joining Star, competition must be allowed into the Austrian and German markets, which otherwise would be dominated by Star carriers.

AAG and Lufthansa complained that the conditions were harsh (but what did they expect given the grip Star would have in the region?) These conditions included restrictions on price–cutting on routes between Germany and Austria, a "request" to the relevant domestic authorities that eastern European airlines should be granted seventh freedom rights, a two–year ban on increasing frequencies on any route on which a competitor enters, and a requirement that Lufthansa and AAG give up 40% of their slots on routes between the two countries.

The results have been encouraging (from a competition point of view, not from AAG's) and new entrants include Adria Airways, Air Alps and Styrian Spirit, the latter a Graz–based start up that has just launched and will operate several routes between Germany and Austria in the summer of 2003 with CRJ200s.

Another potential start–up, Fairline, is planning to operate two turboprops out of Graz on "new routes".

Vienna is already served by germanwings, flying from Cologne/Bonn (although, being part–owned by Lufthansa, it cannot be considered a threat), as well as Air Berlin. Ryanair serves Salzburg, Graz and Klagenfurt, while Aero Lloyd also operates to Vienna and is reported to be considering basing an operation there (to be called Aero Lloyd Austria), to serve charter destinations outside the EU. This airline should start operations in time for the summer 2003 season and would serve up to 20 destinations.

AAG management insists that opening up routes to greater competition is a tough price to pay for the Star approval and AAG will retain its leading position in the Austrian market. The alternative scenario — that AAG joined a different global alliance — would have precluded the opening up of new competition in the short–term, but AAG would have been faced by the far greater problem of having to compete with Lufthansa and its Munich hub. Bearing this in mind, the new entrants should be seen by AAG as a minor irritation and a price worth paying for linking up with Lufthansa and Star.

A greater threat to AAG comes not from new airline entrants on the odd route or two, but from the potential development of a rival east–west hub, which would eat into the 23% of AAG revenue in 2002 that came from eastern, central (excluding Austria) and southern Europe (the latter is not separated out in AAG’s accounts).

Vienna is certainly an interesting airport to have as an east–west hub. AAG has a stranglehold there — AAG’s own estimates are that its six–waves of flights at the airport have given it a 66% market share, which it aims to increase to70% by 2006. Transfer passengers as a proportion of total passengers served at Vienna has risen from 19.7% in 1996 to 34.9% in 2002. Yet Vienna is certainly not a low–cost facility — particularly when compared against alternatives not so far away in eastern Europe.

Both Bratislava and Budapest, for example, are much lower cost airports. Perhaps in response to speculation that other airlines are already looking at establishing an east–west hub at these locations, Vagn Sorensen has said that: "If we plan to start our own low–cost airline, I want to do this in Bratislava." Building an operation at Bratislava, just 50km away from Vienna, may look attractive to AAG as a defensive move given impending Slovakian membership of the EU, which will inevitably attract interest from other EU airlines, and the fact that Slovakia only has two or three tiny scheduled airlines at present.

The latest is SkyEurope Airlines, which launched in February 2002 and is half–owned by Spain’s SwiftAir. SkyEurope operates to seven destinations (including Berlin, Munich and Milan) with three Emb–120s.

Currently AAG serves more than 30 central and east European destinations — more than any other European airline — although they are believed to be of mixed profitability.

The most profitable routes are estimated to be to Bucharest, Kiev and Sofia, closely followed by Tirana and Belgrade. With LOT scheduled to join Star in October 2003 (it has now ended its alliance with British Airways), the Star grip on eastern Europe seems stronger than ever, but the last development it would want is anyone else encroaching into what is seen as AAG territory.

Time to sort out the balance sheet

So what does the future hold for AAG? Operationally, as long as AAG can meet the threat of new competitors out of Austria and keeps an eye on any hub development at Bratislava, the challenges to such a well–run niche player that is protected by membership of a global alliance should not be great.

The greatest danger to AAG is financial: its long–term debt at the end of 2002 stood at €2.4bn — still too large for a company of AAG’s size. Net gearing is a disturbing 290%.

AAG’s shareholders will certainly be keeping a close eye on the finances.

Currently the Republic of Austria (via state holding company OIAG) owns 39.7% of AAG, with a syndicate of Austrian institutional investors owning 10.6%.

In July 2002 AAG bought 5% of its shares from Credit Suisse First Boston for its employee share scheme, leaving CSFB with a 5.15% shareholding — the remaining part of the AAG equity it acquired from Swissair in 2001.

Air France still has its 1.5% share, with the rest on free float on the Vienna stock exchange.

These shareholders have seen the share price fall from above €30 in 1998 — when it posted its best net result in its history — to just over €6 in late April 2003, and dividends are suspended at the moment. With the turnaround strategy under implementation, investors will be looking for debt to be reduced and then a return on their investment sometime soon.

| Fleet | Orders | |

| Austrian Airlines | (Options) | |

| A319 | 1 | 6 |

| A320 | 8 | |

| A321 | 6 | |

| A330 | 4 | |

| A340 | 4 | |

| 737-800 | 3 | |

| MD-80 | 9 | |

| F70 | 4 | |

| Total | 36 | 9 |

| Lauda Air | ||

| 737-3/400 | 2 | |

| 737-6/7/800 | 7 | 1 (4) |

| 767-300ER | 4 | |

| 777-200ER | 3 | |

| CRJ100LR | 3 | |

| Total | 19 | 1 (4) |

| Tyrolean Airways | ||

| Dash 8 | 18 | |

| CRJ200LR | 13 | 3 |

| ERJ-145 | 3 | 1 (3) |

| F70 | 6 | |

| Total | 40 | 4 (3) |

| Group total | 95 | 14 (7) |