AirTran: High-quality LCC with big ambitions

Feb/Mar 2007

AirTran Airways, which is now leading the way in alliance–building and possible consolidation among US LCCs with its recent marketing deal with Frontier and ongoing hostile takeover bid for Midwest Air Group, is one of the best–performing US carriers. It has an eight–year profit record, an innovative business model and extremely low unit costs — its stage length–adjusted non–fuel CASM has now crept below Southwest’s, even though it offers a business class on all flights. But AirTran needs to diversify away from the competitive East Coast markets and reduce reliance on the Atlanta hub, which it shares with the soon to- be revitalised Delta.

The proposed merger would be an ideal solution to the strategic challenges faced by both airlines. There would be unique network and fleet synergies and no regulatory concerns. The deal probably represents Midwest’s best chance because this higher–cost, up–market airline, having miraculously avoided LCCs in the past, is extremely vulnerable to future competitive incursions into its Milwaukee hub. Most in the industry believe that this deal will ultimately get done. What are AirTran’s plans for the combined carrier? And could Frontier also play a role?

AirTran is fortunate in that it was in great shape when the industry crisis began in 2001. It had just staged an impressive financial turnaround in 1999–2000, following three years of heavy losses as it rebuilt operations and restructured itself after predecessor ValuJet’s 1996 crash and three–month grounding. The company had retained a low cost culture despite becoming a more up–market and conventional type of operation. It had also raised its unit revenues by 52% between 1997 and 2000, introduced the 717 to its fleet in 1999, obtained lease financing on highly favourable terms for the first three years' deliveries and completed a major debt refinancing in early 2001. With all of those issues resolved, AirTran was ready to start growing (see Aviation Strategy, March 2001).

As a result, AirTran went against the industry trend by accelerating growth and fleet renewal in the wake of the post- September 2001 crisis. ASM growth was stepped up from 7% in 2000 and 12% in 2001 to 26% in 2002, and growth remained in the 20–30% range in each of the past four years. Last year’s capacity growth was 23.7%, making AirTran probably the fastest–growing of the US non–regional carriers.

The main benefit has been significant cost savings from fleet renewal. AirTran’s ex–fuel unit costs have declined by 14% in the past five years. Also, the strategy enabled AirTran to quickly take advantage of the old US Airways' downsizing, while continuing to successfully fend off Delta at Atlanta.

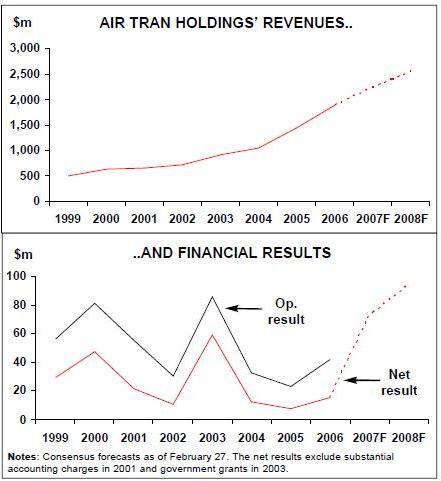

AirTran has tripled its annual revenues in the past six years, from $624m in 2000 to $1.9bn in 2006. It has transformed itself from a struggling LCC into the tenth largest US carrier, only slightly smaller than JetBlue. Although AirTran did not achieve the spectacular high–teens operating margins posted by JetBlue and Southwest before fuel prices started rising a couple of years ago, it has posted operating and pretax profits for eight consecutive years — a feat accomplished by only two US non regional carriers (the other is Southwest). AirTran’s operating margins declined from 11–13% in 1999–2000 to the 4–9% range in 2001–2003 and, because of fuel, further to the 2–3% level in the past three years. For 2006 the airline reported operating and net profits of $42.1m and $15.5m respectively, representing 2.2% and 0.8% of revenues.

AirTran’s profits in the past two years have suffered also due to industry capacity addition on the East Coast, its own rapid expansion and a decline in short–haul demand in the aftermath of the August 2006 London terrorist scare. The airline was the industry’s worst unit–revenue performer in the fourth quarter of 2006, seeing its PRASM fall by 7.1%, which contrasted with the industry (ATA) domestic PRASM gain of 5.5%. Also, AirTran saw its 4Q operating profit halve to $2.5m and it reported a $3.3m net loss for the latest period, compared to break–even a year earlier.

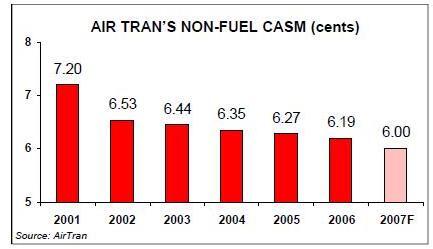

The fourth quarter loss was incurred despite impressive unit cost performance. AirTran’s CASM was down by 5.6%, helped by a 7.7% reduction in fuel prices (the average stage length was flat). Ex–fuel CASM fell by 4.1% to 5.94 cents — a record low for the airline.

Attaining cost leadership

AirTran’s quarterly results have fluctuated considerably in the past two years as a result of Delta’s erratic behaviour before and during its bankruptcy. The airline is vulnerable to Delta’s actions because 66% of its capacity is in the Atlanta markets. After filing for Chapter 11 in September 2005, Delta initially cut back sharply, reducing its seats in AirTran’s Atlanta markets from 80,000 in May 2005 to less than 60,000 by January 2006. But in September Delta began adding back capacity, increasing the seats to 70,000 by November. Although the latest developments are again positive — Delta is removing about 12% of the November capacity this spring — it all basically underlines AirTran’s need to diversify its route network. AirTran’s ex–fuel unit costs have declined for five consecutive years — from 7.20 cents per ASM in 2001 to 6.19 cents in 2006 — and a further 3% reduction, to about six cents, is anticipated in 2007. This trend is driven by the increasing mix of the larger 737s in the fleet, as well as continued improvement in overall efficiency and reductions in distribution costs.

Even though AirTran is primarily a hub–and- spoke carrier, it has always operated the Atlanta hub using the more efficient free–flow system that the legacy carriers have been switching to in recent years.

This explains why it has relatively high average aircraft utilisation for a short haul carrier (11 hours daily in 2006). Notably, AirTran has industry–leading employee efficiency; its 60.4 FTEs (full–time equivalent employees) per aircraft in the fourth quarter was slightly below Southwest’s and significantly below JetBlue’s.

AirTran is now the lowest–cost carrier in the US on a non–fuel, stage length–adjusted basis, having overtaken Southwest in 2006. On a total CASM basis (including fuel costs), AirTran estimates that its stage length–adjusted unit costs were 11% higher than Southwest’s in 2006 but that the differential will reduce to 3% in 2007 as Southwest’s fuel costs continue to rise due to its weakening hedges.

But what matters more is how the unit costs compare with Delta’s. AirTran claims that its cost advantage over Delta has widened from what it was five years ago, despite Delta’s Chapter 11 restructuring. In AirTran’s estimates, its stage length–adjusted non–fuel CASM in the second quarter of 2006 was 39% below Delta’s, compared to a 30% differential five years earlier.

Successful product strategy

AirTran has always stressed that the key to coping with Delta is keeping costs low. Explaining the management philosophy at a recent conference, president/COO Bob Fornaro noted that "it’s really the only way we can manage the business". From time to time, Delta will add capacity and AirTran’s margin declines. Then Delta will take out capacity and AirTran’s margin improves. "But they cannot impact on our costs."Aside from the RASM and yield challenges resulting from capacity addition, AirTran has a highly successful product and revenue strategy. The airline caters for all passenger segments, but its model is more specifically designed to meet the needs of business travellers than the Southwest and JetBlue models are. It offers "key attributes of major airlines at affordable prices". This includes a separate business class cabin, featuring two–by–two oversized seating and more legroom, for $40-$80 extra per segment; assigned seating, XM satellite radio (AirTran was its launch customer in 2004) and a range a booking channels (including travel agencies).

In contrast with JetBlue, which realised only last year that it needed to use sophisticated yield management, AirTran has always had such systems in place to maximise revenues. It offers a simple fare structure, with prices varying according to how early bookings are made (fourteen, seven or three days in advance, or walk–up). The airline participates in all the major GDSs.

These strategies have been instrumental in pulling in business traffic. AirTran has an enhanced quality image and has consistently ranked high in customer satisfaction surveys. However, like the other US LCCs, AirTran now faces more efficient and aggressive legacy carriers and needs to make extra efforts to improve revenue generation.

Fleet and route expansion

One of the hottest new trends among US LCCs is growing ancillary revenues — something that even Southwest is now focusing on. AirTran’s "other" revenues surged by 50% to $73m last year. However, AirTran has not mentioned any new ancillary revenue initiatives; rather, all of its current efforts seem focused on developing new geographic sources of revenue — meaning route expansion, alliances and mergers. AirTran’s fleet development has had two distinct phases. First, the airline replaced its original DC–9 fleet with the 717–200s in 1999–2003. The last DC–9s were retired in January 2004. Following an order for ten additional 717s in 2003, the final two 717s were delivered in 2006 — the year when Boeing stopped 717 production. The type is ideally suited to AirTran’s typical short–haul operations (its average stage length was 652 miles at year–end).

Second, AirTran added a second aircraft type, the 737–700, to its fleet in 2004, after placing an order for up to 100 737- 700/800s in 2003. The type has facilitated growth, as well as longer–haul operations, including flights from Atlanta and other points in the East to the West Coast. The airline noted recently that the 737 offers opportunity to expand also to Canada, Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, "should we choose to do so".

Both the 717 and the 737 fleets have been obtained at bargain prices. The initial 717 order was originally ValuJet’s $1bn 50- aircraft order for the MD–95 in 1995, benefiting from launch customer pricing. The 737–700/800 order, in turn, was perfectly timed in the wake of the post–2001 industry crisis, securing massive discounts because no other US airline was ordering aircraft.

AirTran now has one of the youngest fleets in the industry, with an average age of about three years. The fleet included 127 aircraft at year–end — 40 737s and 87 717s — plus 60 737s on firm order for delivery in 2007–2011. In September the airline pushed back some deliveries to 2009–2011 and since then has also agreed to sell two 737s due this April (to a non–US airline), in order to reduce near–term capacity growth. After receiving 22 new aircraft in 2006, AirTran is taking ten 737s this year, followed by 15 in 2008. This year’s ASM growth is expected to be 19% — still much faster than the growth rates planned by other US LCCs — though the 12% increase currently envisaged for 2008 is more conservative.

Since 2000 AirTran’s network has evolved basically in three ways. First, there are now coast–to–coast flights and generally more east–west flying. Second, non- Atlanta flying has increased from 10% in 2001 to 34% in January 2007. Third, with several years of rapid growth, the airline has significantly strengthened the East Coast network by adding destinations, developing focus cities, connecting the dots and boosting frequencies.

Therefore, despite the obvious weaknesses (Atlanta’s dominance and the huge blank spaces in the western half of the country), AirTran has gained competitive market mass. As many as 16 of its cities (compared to only two five years ago) have service to at least five destinations; the top five are Atlanta (52 destinations), Orlando (24), Baltimore/Washington (13), Tampa (11) and Chicago (10). Furthermore, even though AirTran lacks the power typically wielded by a dominant operator at a hub, its Atlanta operation, with 215 daily departures in January, is among the nation’s largest mainline hub operations, similar in size to Southwest’s Las Vegas, US Airways' Charlotte and Continental’s Newark hubs.

AirTran typically aims to add 4–5 new cities per year, plus numerous new connections between existing cities. Last year saw two new destinations — Seattle (Washington) and White Plains (New York) — and over 20 new non–stop routes. As of March 1, the airline had launched or announced six new cities in the first half of 2007, including Newburgh (New York), Phoenix (Arizona), St. Louis (Missouri) and Charleston (South Carolina), as well as seasonal service to Daytona Beach (Florida) and San Diego (California), and 20–plus new non–stop routes. Many of the new services will be operated from Atlanta, using new gates acquired last summer, but the airline has also announced expansion from Baltimore and Orlando.

Alliance and merger plans

The new east–west services to Seattle, Phoenix and San Diego make much sense strategically and will help reduce seasonality. Newburgh may sound like a less obvious choice, particularly since JetBlue also started Florida service from there in January, but the airport, just 55 miles north of New York City, is poised to become another major gateway to the metropolitan region and is even building an international passenger terminal. AirTran believes that it is well positioned to compete with JetBlue there because its costs are lower, because it also serves the business–oriented Atlanta market from Newburgh and because it has a better schedule. AirTran announced a marketing alliance with Frontier, a Denver–based LCC, in mid- November. This "online and call centre" referral and FFP partnership is the first of its kind between US LCCs. It means that both airlines include an integrated route map and a full list of destinations on their web sites and refer customers to each other. Customers can earn and redeem frequent- flyer miles on either carrier.

The alliance, which AirTran describes as "low–complexity" (a concept that is particularly important to LCCs), is significant in that it links AirTran’s East Coast network with Frontier’s western US network, doubling the destinations available to customers and providing a platform for possible code–shares in the future. It could work well because Frontier’s situation is broadly similar to AirTran’s — a hub–and–spoke LCC having to share its DIA hub with United — though Frontier faces much worse challenges, because it is smaller than AirTran, with a much weaker network, and because Southwest has been building service out of DIA since January 2006.

Subsequently, in mid–December AirTran went public with an unsolicited $290m offer to acquire Midwest Air Group, the parent of Midwest Airlines and regional carrier Skyway Airlines, in a cash and stock transaction. This was not a new idea; AirTran had evaluated Midwest for almost two years, and Midwest had turned down its first offer in the summer of 2005.

Since the rejection of the mid–December offer, AirTran has taken its case directly to the Midwest shareholders by launching a tender offer for the company, increased the price by 18% (valuing the offer at $345m) and extended the tender offer deadline twice (currently April 11). AirTran has also nominated three directors for election to the Midwest board at the company’s annual shareholders' meeting this spring. Midwest has continued to urge its shareholders not to tender their shares and is trying to pitch its own standalone strategic plan.

While the outcome is obviously uncertain, and the existence of Midwest’s poison pill poses a potential hurdle, many analysts believe that AirTran will ultimately succeed. This is because AirTran is an extremely determined bidder — in the 4Q earnings call, the management stated that the intention was to "do whatever it takes to complete the transaction" — and because the alternative scenario for Midwest is to face LCC competition from AirTran, Southwest and others in its key markets possibly even in the near–term. The Justice Department closed its mandatory review of the merger proposal without challenging it in February.

The merger is potentially attractive because the two have complementary route networks, strong fleet commonality (the largest and second–largest 717 operators), comparable corporate cultures and commitments to quality service. AirTran would be able to upgrade Midwest’s MD- 80s with its new 737s, resulting in CASM reductions. The airline anticipates $60m in annual synergies from the merger, arising from improved fleet and capacity utilisation, MD–80 replacement and increased efficiency in maintenance and other areas.

The merger would create a new nationwide LCC, especially if Frontier is included as a marketing partner. It would have about $3bn in combined revenues in 2007 (AirTran’s estimated $2.3bn plus Midwest’s $700m), making it about the same size as JetBlue but only about 30% of Southwest’s size and a quarter of US Airways' size.

AirTran’s growth plan for the combination would be to, first, expand Midwest’s Milwaukee hub; second, develop Kansas City into a focus city; and third, continue to expand from Atlanta. AirTran regards Milwaukee as an under–served market; other US cities with similar populations, such as Charlotte and Cincinnati, have at least two or three times the daily flights and seats. This obviously makes Milwaukee a very attractive target for future LCC expansion. In a late–February presentation to Milwaukee community leaders and Midwest shareholders, AirTran promised that it would double seat capacity, add 29 new destinations and boost daily departures by 50% (to 215) at Milwaukee by the summer of 2009. The new long–haul destinations from Milwaukee would include Seattle, Vancouver, San Francisco, San Jose, San Diego, San Antonio, Houston, New Orleans, Cancun (Mexico), San Juan (Puerto Rico), Montreal (Canada) and several Florida cities.

Importantly, the merger would result in instant diversification, making the network much better balanced than what either airline has today. AirTran currently has 66% of its capacity at Atlanta, while Midwest is even more highly concentrated at Milwaukee (83%). Combining the companies would reduce Atlanta’s share to 46% and Milwaukee’s to 24%, while Kansas City,Orlando and Baltimore would be focus cities, with 7%, 7% and 5% shares, respectively.

There is understandably sadness and concern in Milwaukee and among Midwest customers about the potential loss of the luxurious product and service provided by Midwest, known as "the best care in the air", which includes wide leather seats with footrests and baked–on board chocolate chip cookies. In its standalone plan, Midwest states that it would continue to provide a "truly differentiated travel experience at a time when other airlines have commoditised flying". AirTran has responded that the Midwest product is not consistent throughout its network because of its RJs and that there is more nostalgia than reality to the carrier’s image. However, AirTran would retain key amenities such as baked–on board cookies and sees prospects for an enhanced product that would combine the best of each airline’s service.

Midwest’s standalone plan envisages 10% annual ASM growth in the next three years, addition of two MD–80s and numerous 30–seat and 50–seat RJs and improving profitability (the airline reported a small profit for 2006, its first since 2000). Critics have made the point that RJs are not well–suited to low–cost competition. AirTran has argued that that plan is "heavily dependent on a benign competitive environment, maintaining significant fare premiums and favourable fuel costs".

Financial outlook

In AirTran’s estimates, the merger would be accretive to earnings at the end of the first full year and "significantly accretive" thereafter. The cash portion of the purchase price would be funded by a new five–year secured credit facility. According to S&P, the acquisition would increase AirTran’s lease adjusted debt by 25% (primarily through the addition of Midwest’s substantial operating lease commitments), but because of the $60m annual synergies, there would be no material impact on credit ratios. Delta’s planned capacity cuts this spring and AirTran’s continued CASM reductions mean that AirTran’s financial outlook is highly favourable. The current consensus forecast is a profit before special items of 79 cents per share in 2007 (compared to 14 cents last year), to be followed by a profit of $1.04 in 2008. These estimates do not include any impact from the possible Midwest merger.

There is nothing on the horizon that could reverse the favourable CASM trend. AirTran is unionised but benefits from generally good labour relations. However, it should be noted that the pilots are currently in mediation over a contract that became amendable in 2005.

Competing capacity is the "key wild card in any earnings scenario for AirTran", as Raymond James analysts put it in a recent report. Delta’s emergence from bankruptcy, expected this spring or summer, should at least initially be good news for AirTran, because Delta will have to focus on profitability and behave responsibly. In the longer–term, however, there is the risk that a stronger Delta could resume aggressive capacity addition in AirTran’s markets.

AirTran’s balance sheet is much weaker than Southwest’s and somewhat weaker than JetBlue’s. The company is highly leveraged due to substantial operating lease commitments; the adjusted debt–to capital ratio is around 90%. Debt and capital lease obligations surged to $811.1m at the end of 2006, from $472.6m a year earlier, due to 737 acquisitions. However, AirTran’s liquidity position is satisfactory; cash amounted to $335m at year–end, representing 18% of 2006 revenues.

Contractual obligations are running at around $1bn annually over the next three years, around half of which are aircraft purchase commitments. But funding the orders should not be a problem. AirTran has secured debt financing for all of this year’s and five of next year’s 737 deliveries. After leasing virtually all of its 717 fleet from Boeing Capital, the company has bought almost half of its 737s. Total assets have increased from $473m in 2002 to $1.6bn at the end of last year.