AirTran: impressive recovery leveraged on 717 assets

March 2001

AirTran Airways, the second largest (after Frontier) of the early 1990s generation of US low–fare airlines, has staged an impressive financial recovery over the past two years, but until recently its prospects were marred by a $230m balloon debt payment due this April. In late January the carrier secured a binding agreement with Boeing Capital Corporation (BCC) to refinance that debt. With the major obstacle removed, AirTran can now focus its efforts on growth, fleet renewal and consolidating profitability.

The debt being refinanced consists of two lots of junk bonds issued by AirTran’s predecessor ValuJet, $150m in April 1996 and $80m in August 1997. Those proceeds, together with ValuJet’s large cash reserves, enabled the company to sustain operations through three years of heavy losses as it rebuilt operations and restructured itself after the 1996 crash and three–month grounding.

However, the need to repay the $230m debt in April 2001 increasingly clouded AirTran’s prospects and kept its share price low. It would not be able to generate enough cash flow from operations to repay the debt, and refinancing it in a weak bond market was quite a challenge for a small airline with relatively weak credit ratings.

As on other occasions in the past, Boeing came to the rescue. In a deal reached in principle in November and finalised in late January, BCC agreed to provide $220m in debt and equity instruments, with the remaining $10m coming from internally generated funds. At current interest rates, the all–in financing cost over the seven–year term of the loan will be 11.25- 11.75%, which is probably less than what AirTran would have paid in the current public junk bond market.

AirTran will now retire the existing $230m of debt in mid–April. Clearly, as many analysts point out, eliminating the refinancing risk far outweighs the negative effects, namely common stock dilution of up to 8% (which will reduce EPS growth) and higher interest costs. The company’s share price has recovered strongly since the Boeing deal was announced. Also, Standard & Poor’s recently raised AirTran’s credit ratings by one notch, citing the refinancing and improved earnings and cash flow.

Boeing’s involvement was hardly surprising in light of AirTran’s 717 launch customer status and substantial order commitment (originally ValuJet’s $1bn 50–aircraft launch order for the MD–95 in 1995). In May 2000, as AirTran began to feel the burden of high interest expenses following the purchase of the initial ten 717s, Boeing agreed to provide lease financing for the next 20 717s on highly favourable terms, covering deliveries up to February 2002.

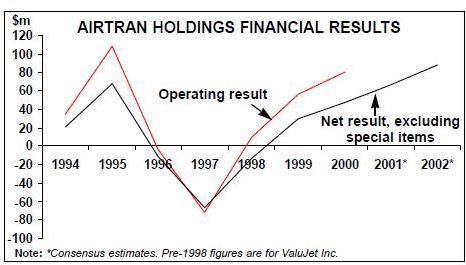

Strong financial recovery

AirTran returned to profitability in 1999, when a $147.7m DC–9 fleet disposition charge is excluded. This followed three years of losses totalling $91m excluding restructuring charges (or $179m if charges are included), as predecessor ValuJet, under the guidance of former CEO Joseph Corr, rebuilt operations, acquired and merged with AirTran, changed its name and put in place strategies to improve its image.

The current chairman/CEO Joseph Leonard, who took office in January 1999, focused on cost controls and refining revenue strategies. Profitability was restored as unit costs were reduced and yields and load factors recovered substantially. Leonard and his management team are highly regarded by Wall Street.

AirTran reported a $47.4m net profit on revenues of $624.1m for 2000, up 63% and 24% respectively on the 1999 results. Operating profit rose by 45% to $81.2m, representing a 13% margin — the second highest in the US industry after Southwest’s 18.1%.

The results were impressive in light of the extremely challenging operating environment.

AirTran’s own fuel expenses more than doubled last year. The carrier also talked of a significant slowdown in ATC efficiency at its Atlanta hub and at critical Northeast airports, which it estimated reduced average speed over its entire system by 30 miles per hour.

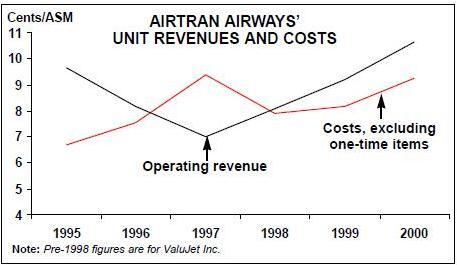

Like Frontier, AirTran has posted double–digit unit revenue growth in the past two years, largely thanks to success in attracting business traffic. Operating revenue per ASM surged from 8.1 cents in 1998 to 10.65 cents last year. Business class load factor rose from just 35% in 1998 to 60% last year, while system load factor improved from 60% to 70%.

The carrier attributed last year’s strong revenue growth, first, to more aggressive marketing and having a better knowledge of its customer base and booking patterns. Second, competition eased up in key East Coast markets, as MetroJet pulled out of several markets and United slowed capacity growth at Washington Dulles.

In recent months AirTran may also have benefited from increased flight delays and cancellations at Delta, whose pilots have sporadically been refusing to work overtime during the ongoing difficult contract negotiations. However, the benefit, if any, has been nowhere near the level experienced by Frontier last year because of United’s operational problems.

AirTran’s unit costs fell from 9.40 cents in 1997 to 8.19 cents in 1999, which was a real achievement given its switch to a more conventional organisational structure, maintenance and compensation methods. Inevitably, unit costs surged last year because of fuel (to 9.27 cents), but non–fuel unit costs actually declined by 1%.

Like other airlines, AirTran has benefited from lower distribution costs. Internet sales have risen rapidly to account for 37% of total sales (29% through its own web site). The carrier estimates that the cost of booking a passenger on the Internet is just 50 cents, compared to $8.50 via a travel agency.

Against earlier expectations, AirTran has retained a low cost culture despite becoming a more up–market and conventional type of operator. It appears to continue to enjoy a substantial cost advantage over its main competitors — by its own estimates, at its average stage length of 537 miles, Delta, United and US Airways have 30%, 50% and 90% higher unit costs respectively.

AirTran’s balance sheet, which was earlier weakened by substantial restructuring charges related to ValuJet’s shutdown, rebranding and accelerated aircraft retirements, has also begun to recover, led by a dramatic improvement in cash position. The company had $103.8m in cash at year–end, compared to just $10.8m at the end of 1998. Stockholders' equity, which plunged to a deficit of $40m at the end of 1999 as a result of the DC–9 fleet write–down, recovered to $7.9m positive at the end of last year.

While total liabilities have remained relatively constant ($450m at year–end, including the $230m debt that was reclassified from current to long term last year), this year may see a modest reduction. CFO Robert Fornaro indicated recently that if excess cash is generated this year, it would probably be used to pay down debt early.

Impact of the Boeing 717

AirTran may have paid as little as $20m per aircraft — and it got a major say in the 717’s design specifications. The aircraft, introduced to service in October 1999, is ideally suited to AirTran’s short haul, high–frequency East Coast markets. The airline operates it in 117- seat, two–class configuration, gaining a useful 11 extra seats or 8% more capacity over the DC–9.

Moving to a brand new fleet will obviously improve operational reliability and enhance image. The average age of AirTran’s aircraft is projected to almost halve in three years, from 22 years at the end of 2000 to 12 years at the end of 2003, as the 717s replace the carrier’s DC–9s and 737s.

But, most importantly, the 717 offers a major reduction in maintenance and fuel costs over the late 1960s and early 1970s–vintage DC–9s. The aircraft has achieved a 24% better fuel burn over the DC–9, compared to 18% guaranteed by Boeing. It will help AirTran maintain its unit cost advantage over competitors.

The fleet currently includes 17 717–200s, 33 DC–9–30s and four 737–200s. The 33 717s currently on firm order will arrive at a rate of one aircraft per month through October 2003. There are also 25 options, 20 purchase rights and five rolling options for additional 717s for delivery before October 2005.

The 737 retirement process may begin in the second half of this year. The current plan is to reduce the DC–9/737 fleet by about five aircraft a year to 23 at the end of 2003. However, there is obviously flexibility to slow down or accelerate retirements to suit market conditions. Also, AirTran’s top executives have indicated that the company would be happy to pick up additional 717s if any of the TWA orders are cancelled. Now that the debt refinancing issue is out of the way and fuel prices look likely to remain high, the company is leaning in favour of accelerating DC–9 retirements.

Stable labour relations

The large 717 orderbook, which not so long ago seemed rather extravagant for a struggling low fare carrier, is now one of AirTran’s greatest assets. However, financing such a large commitment will be a continued challenge for a small company with a relatively highly leveraged balance sheet and weak credit ratings. Like most other US airlines, AirTran remains under pressure on the labour cost front. Last year its labour costs rose by 13.8%, due to contractual and seniority pay increases, increased block hours and more pilots moving to the 717 training programme. New contracts signed in recent years have included competitive wages and annual pay increases.

But labour relations appear to be stable. Last year AirTran’s customer service, ramp and reservation agents rejected union representation. In October the mechanics, represented by Teamsters, ratified a new five–year contract. And, most importantly, in late January tentative agreement on a new five–year contract was reached with the pilots, represented by NPA, two months before the amendable date.

Winning higher yield traffic

AirTran describes its product strategy, which focuses on both leisure and business travellers, as offering "key attributes of major airlines at affordable prices". While its walk–up fares are generally 60% below those of high–cost competitors, it has also developed a very successful business class product, which is offered for only $25 extra per segment, and an innovative "A–Plus Rewards" FFP.

These strategies have been instrumental in pulling in higher–yield traffic. AirTran has virtually reversed its former 40%/60% business/leisure revenue mix in just two years. Its business class fares now account for 56- 58% of its total revenues.

AirTran focuses on short haul markets in Eastern US, where it enjoys the greatest cost differential over competitors. The strategy is to serve large primary business centres and develop under–served secondary markets, particularly those that suffer from high fares.

The airline has established a successful hubbing operation at Hartsfield Atlanta, where it has a 22–gate single concourse facility and room for growth. Atlanta has a large local traffic base and is ideally located for attracting connecting passengers. Traffic growth there has averaged 8–9% annually since the early 1990s, compared to 4% nationally, and is projected to grow by 6% annually over the next few years. Of course, the market is overwhelmingly dominated by Delta, but AirTran is the second largest carrier with 9% and 12% passenger and departure shares.

Atlanta accounts for 90% of AirTran’s passenger flows, but in recent years the carrier has developed point–to–point services elsewhere in the East. These include Chicago/Midway–Minneapolis, Pittsburgh to Chicago and LaGuardia and Philadelphia to three Florida cities.

While AirTran intends to continue strengthening its position in Atlanta, it also sees some great market opportunities in the Northeast, given "big cities, short distances, high fares". It appears to have chosen Pittsburgh as a new focus city and is also keen to grow from Philadelphia and LaGuardia. Also, the airline would like to have a substantial hub operation at Washington National.

The main problem, of course, is lack of slots and gates at many of those airports.

Consequently, AirTran has taken a very aggressive stance in respect of the divestiture of slots that is likely to take place if the United–US Airways merger is allowed by the regulators.

In late February the carrier filed formal complaints with the DoT about a potential United–American "monopolisation" of the Washington National market. It is asking the DoT to order the reallocation of slots at National to new–entrant or limited incumbent carriers, regardless of the outcome of the pending airline mergers. AirTran argues that, if the proposed deals go through, United and American would control 66% and 80% of the National and Dulles markets respectively.

It is possible that the DoT may not want to complicate the already extremely complex regulatory issues associated with a major airline merger scenario with new–entrant issues. AirTran is certainly not counting on it for growth opportunities.

Prospects

After two years of marginal growth and consolidation, AirTran has entered a new growth phase. Its ASMs are projected to increase by about 20% both this year and in 2002. But the favourable unit revenue trend is expected to continue, as more 717s are added and a new revenue management system, introduced in December, kicks in fully.

AirTran expects its non–fuel unit costs to go up by 2–4% in 2001, mainly due to contractual wage increases, automation expenses and aircraft rents. While the growth of the 717 fleet will have a favourable impact on fuel and maintenance costs, analysts believe that those savings will be offset by considerably higher ownership costs (rental expenses).

The carrier has budgeted for fuel at around $1 per gallon, net of fuel hedge benefits. It has hedged 50% of its first–quarter needs at $29 per barrel and 30% of its needs in the remainder of the year at $24.

The current consensus forecast is a profit of 97 cents per share for 2001, which would represent a 35% increase, and a profit of $1.27 per share for 2002 (including the dilutive impact of the Boeing transaction).

Now that the debt repayment risk has been eliminated, the main risk factor mentioned by analysts is AirTran’s presence in the congested and fiercely competitive East Coast market.

However, the carrier is expected to retain its cost advantage and may even face a reduced threat from its number one competitor, Delta.

Atlanta–based James Parker, analyst with Raymond James, believes that AirTran can continue to profitably coexist with Delta, first, because its costs are so much lower. Second, it will probably expand capacity only modestly above market growth in Atlanta so as not to threaten Delta. Third, there is now greater scrutiny by the regulators regarding predatory practices. Fourth, business travellers are resisting the high and rising fares of the major carriers. This will even more be the case if the economy slows further.

| In | On | ||

| operation | order | Options | |

| 717-200 | 17 | 25 | 50 |

| 737-200 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| DC-9-30 | 33 | 0 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 54 | 25 | 50 |