Air Canada: Continued labour and financial challenges

June 2011

Since its close brush with extinction in the summer of 2009, when it had to be bailed out by its unions and the government, Air Canada has rebuilt its cash position, achieved impressive cost cuts and even turned modestly profitable on an operating basis (in 2010). It is well positioned to benefit from the recovery of global business travel.

However, Air Canada continues to under–perform other global carriers in terms of profit margins and unit revenues. Renewed labour challenges and escalating low–cost competition in key markets raise into question its longer–term survival.

Air Canada’s most important challenge is to clinch new contracts with its labour unions that facilitate crucial pension reforms and additional cost cutting, without which the airline will not be viable in the long run. The contracts of all of the four major unions have become amendable in recent months.

The workers are opposed to further giveaways, especially on the pension front.

The strength of labour opposition to the pension proposals was illustrated by the three–day mid–June strike of Air Canada’s customer service and sales employees. Agreement on a tentative four–year contract was only reached after the Canadian government followed through on a threat and submitted legislation that would have forced an end to the strike. The deal provides for wage increases (reportedly 9% over four years) and “slight” changes to existing employees’ pension plans. However, the tough issue of whether new hires will be eligible for a defined–benefit pension plan will go to binding arbitration.

While there is currently no threat of labour action from the other three groups, Air Canada faces a summer (or longer) of difficult labour dealings. Its pilots recently rejected a tentative agreement reached in March but are expected to get back to the negotiating table. The flight attendants and the mechanics have remained firm on the pension reform issues, and the flight attendants have asked for federal mediation.

Additional cost cuts are critical because Air Canada faces growing competition in all of its key markets. Within North America, it faces a revitalised US legacy sector and an LCC sector that is capturing market share and increasingly also targeting business traffic. In long–haul international markets, there is new competition in all shapes and sizes, including Middle Eastern carriers such as Emirates and Etihad; the Canada–UAE trade dispute over air services is illustrative of the new pressures that Air Canada is under.

It is a point of concern that, despite the 2009 bailout, Air Canada has continued to financially under–perform its key competitors. In 2010 — its best year in a decade, and one in which many US legacies achieved 10%-plus operating margins — Air Canada had only a 3.3% operating margin. And there is no clear indication that it could catch up: the best that most analysts foresee for the next few years are low–single digit operating margins.

However, Air Canada enjoys many inherent advantages. First, it has a great global route franchise. Second, it still has leading market shares in the Canadian domestic, USCanada transborder and long–haul international markets. Third, it offers a superior product and service quality (at least compared to the US legacies), making it well–positioned to retain and attract premium traffic. Fourth, it belongs to what is arguably the strongest of the three global alliances (Star) and will increasingly benefit from robust joint ventures.

So Air Canada is pressing on with efforts to achieve “sustained profitability” in the longer–term (there is no talk of margin or ROIC goals, as at the US legacies). The key strategies include continued cost transformation, making the corporate culture more “customer–centric and entrepreneurial”, building on the Air Canada brand and global network, and de–leveraging the company. Air Canada’s international growth efforts include the very interesting strategy of trying to capture incremental sixth freedom premium traffic between the US and Asia/Europe through Toronto and other Canadian hubs. Is that strategy paying off?

But the growth efforts also include the risky proposal to establish a separate LCC subsidiary to tackle more leisure–oriented international markets. While labour may well pose an obstacle to such a venture, why would Air Canada even want to consider it, given the poor track record of LCC units operated by legacy employees?

Even though there is probably little chance of Air Canada ever disappearing – its formidable global franchise and dominant role in the Canadian aviation market probably ensure that partners, banks or the government would always step in to provide assistance or more funds – the airline needs to stop what seems like a slow but steady decline into oblivion. Will the current and planned strategies do the trick?

Mediocre results despite bailouts

Few global carriers have received as much help as Air Canada in terms of bailouts, restructurings (in and out of bankruptcy), labour concessions and pension relief in order to get their houses in order. To start with, Air Canada completed an 18- month bankruptcy reorganisation in September 2004, which reduced its net debt and capitalised leases from C$12bn to C$5bn and gave it a relatively healthy cash position of C$1.9bn (C$1=US$1.02). But the cost cutting programme initiated in bankruptcy fell far short of giving the airline a competitive cost structure (see Aviation Strategy briefing, November 2004).

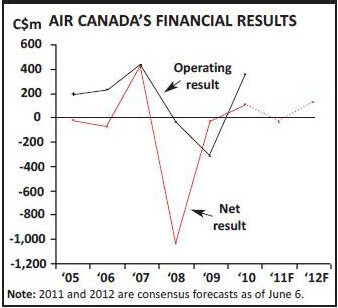

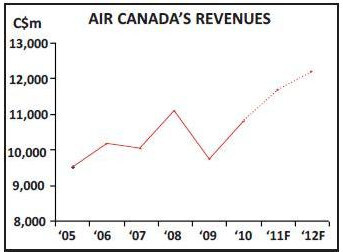

Air Canada was never able to consolidate the promising early turnaround seen in late 2004 (in the wake of three and a half years of losses totalling C$1.7bn). It achieved only marginal operating profits in 2005–2007 (2- 4% of revenues) and plunged back into losses in 2008–2009. It had an annual net profit only once in the last decade (in 2007).

The airline’s finances deteriorated rapidly in early 2009 as the global recession began to bite. By May 2009 Air Canada was in a crisis, with cash reserves amounting to only C$1bn or 10% of annual revenues, which would not have covered the debt and pension obligations in the subsequent 12 months. New CEO Calin Rovinescu, who had taken over in April 2009 after Montie Brewer’s resignation, set about to find creative solutions to avert bankruptcy (Aviation Strategy briefing, July/August 2009).

Air Canada regained financial stability after successfully addressing its key issues in the summer and autumn of 2009. First, it secured agreements with its unions on two–year contract extensions on a “cost neutral” basis and a 21–month pension–funding moratorium, with payments capped for a further three years. Second, the labour deals enabled Air Canada to raise C$1.4bn in new liquidity, to bring its unrestricted cash to 15% of annual revenues (one of its key financial targets). Third, Air Canada renegotiated contracts with suppliers, vendors and credit card providers, including its capacity purchase agreement with regional carrier Jazz. Importantly, in mid–2009 Air Canada also launched a three–year “Cost Transformation Programme” (CTP), aimed at generating C$530m of annualised cost savings and revenue gains by the end of 2011.

Since then Air Canada has made further significant progress on many of these fronts. A C$1.1bn debt offering in 2010 helped bring year–end cash reserves to C$2.2bn or 20% of annual revenues – the highest in the airline’s history. Air Canada is also exceeding the CTP plan targets, having achieved C$440m or 83% of the total targeted annual benefits by early May. Ex–fuel CASM declined by an impressive 4.5% in 2010 and by another 5.3% in this year’s first quarter.

As a result of the cost cutting, economic recovery and favourable currency developments, Air Canada achieved a modest financial turnaround in 2010, recording operating and net profits of C$361m and C$107m, respectively, on revenues of C$10.8bn. The March quarter saw continuation of the recovery trend, with operating losses narrowing to C$66m from the year–earlier C$136m, despite the significant fuel price hike.

But Air Canada’s operating margins continue to lag those of its peers. In the first quarter, Air Canada had the second–worst operating margin (negative 2.4%) among the top 11 North American carriers. Only AMR’s margin was weaker (negative 4.2%), but AMR has special reasons for under–performing, including never having been in bankruptcy.

While Air Canada’s main problem continues to be a significant CASM disadvantage over both LCCs and the US legacies, this year it has also under–performed on the unit revenue front, despite the business travel recovery trend. According to BofA Merrill Lynch, its first–quarter currency–adjusted 2.4% RASM increase was nearly six points below US airlines’ and ten points below WestJet’s. (Air Canada did see a healthy 13% increase in premium–cabin revenues but it was mainly volume–driven.) Long–haul markets were largely to blame.

Air Canada has been adding much capacity to Europe and Asia, though industry capacity too was up significantly in the transatlantic market in the traditionally weak first quarter. According to BofA Merrill Lynch, on the European routes Air Canada’s currency–adjusted RASM fell by 2.4% in the first quarter, compared to a 0.8% decline for US carriers. On the Asian routes, Air Canada’s currency- adjusted 2.9% RASM decline contrasted with an 11% gain recorded by the US carriers.

Despite fuel, most global airlines, including all the US legacies except AMR, are likely to remain profitable in 2011, thanks to a combination of fare increases, fuel surcharges, capacity discipline and continued recovery of business travel.

However, Air Canada is expected to plunge back into losses in 2011. The current consensus estimate for 2012 is a modest profit of around C$130m.

Air Canada is pursuing all the possible remedies. On the capacity front, it has followed the US legacies lead and trimmed this year’s growth plans by two points since February. After last year’s 7% growth, system ASMs are currently slated to increase by 3.5- 4.5% in 2011, with domestic capacity decreasing slightly. The growth will be mainly driven by new US and long–haul international services added in 2010 and will be accomplished through increased aircraft utilisation.

Building on the brand and global network

35% of the US–Canada capacity (compared to WestJet’s 15%) and 39% of Canada’s longhaul international capacity. It has well–situated hubs (Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver), a new fleet and one of the world’s best customer loyalty programmes.

Focusing on the brand and international growth made sense also in light of Air Canada’s superior product, service quality and reputation. Air Canada reconfigured its long–haul fleet many years before the US legacies, installing lie–flat seats in its Executive First cabins and seat–back entertainment systems at every seat. Its offerings include a concierge programme and the famed Maple Leaf lounges. Air Canada felt that it had product advantage.

So while cutting capacity in the weakest markets, Air Canada has undertaken a surprising amount of new international expansion since late 2009. Last year saw the addition of five new European gateways — Geneva, Barcelona, Brussels, Copenhagen and Athens; to supplement the carrier’s “European flagship” routes of London, Paris and Frankfurt – and new service to some 15 US cities. The airline also grew significantly on the Pacific, adding flights to China, Korea and Japan.

The new services have supported the post–2009 strategy of trying to attract more global connecting traffic via Canada, which Air Canada only recently began marketing aggressively to US business customers. The selling points are the superior on–board amenities, new airport premium products and the ease of making connections at Canada’s less congested gateways. All of Air Canada’s operations at its Toronto Pearson hub are centralised in a single terminal with streamlined customs procedures, making it potentially very convenient for travel to and from the US. Cities close to the border, such as Seattle, San Francisco, Boston and Pittsburgh, are the most obvious markets.

Air Canada is seeing “encouraging” results from the efforts to capture flow traffic, especially between the Northeast US and Asia–Pacific, and to a lesser extent between the US West Coast and Europe.

As a result of these strategies, Air Canada’s long–haul international revenues have now surpassed its domestic revenues (41% and 40%, respectively, of passenger revenues in 2010; the remaining 19% came from transborder operations).

But in the short term the increased flow traffic may have contributed to the RASM under–performance. While Air Canada may not have had to price too aggressively because of its product advantage, it has had to offer competitive fares to stimulate demand through the Canadian hubs at a time when there is excess industry capacity in the Atlantic and Pacific markets. This summer Air Canada has continued to add much capacity internationally, particularly from Toronto, where it is boosting frequencies to many European cities. However, in the autumn, Air Canada may well trim capacity plans for the winter.

Like its peers, Air Canada will be able to increasingly rely on alliances for growth. There have been two important strategic developments: the transatlantic joint venture with Lufthansa and United Continental, which was finalised in December 2010, and the proposed revenue–sharing transborder joint venture with United Continental, which is awaiting regulatory approvals. The Atlantic JV is already yielding positive results in terms of incremental traffic. The transborder JV has been delayed due to the Canadian regulators’ decision to carry out a full competitive review, but the airlines still hope to implement it this year.

Alliances will be all the more important because Air Canada will remain fleet–constrained until its 787 deliveries commence in late 2013. The airline is due to receive the first two of 37 ordered 787s in 4Q13, and the type will both provide for growth and replace 767s.

Air Canada continues to try to defend its position in the increasingly competitive Canadian domestic market, where WestJet, Porter Airlines and others are aggressively trying to capture business traffic. Armed with weapons such as pre–reserved seating and an FFP, WestJet has greatly expanded in the “Eastern Triangle” business markets.

Porter has built up a sizeable operation from City Airport in downtown Toronto and has siphoned off business traffic from TorontoPearson in key markets such Toronto- Montreal. Air Canada’s recent moves have included rebranding its regional service (including its subsidiary Jazz) as Air Canada Express and using it to resume service at the City Airport in May.

LCC subsidiary plans

As part of its growth strategy, Air Canada has tentative plans to set up a separate low cost subsidiary “within the next year” to target leisure–oriented international markets. However, these plans will require the cooperation of labour, which may or may not be forthcoming.

The management discussed the idea in some detail in the 1Q call in early May. They noted the dismal success rate of the many LCC units launched by legacy carriers a decade ago (including Tango and Zip by Air Canada), but said that they had learned from the experience. In their assessment, the past LCC units had three problems: cost creep, insufficient scale (such as Zip) and yield cannibalisation.

One of the rare success stories Air Canada is using as a benchmark is Qantas’ low–cost unit Jetstar. The management noted that Jetstar has remained extremely disciplined over time on the cost side and did not cannibalise any of the domestic business. The Australian and Canadian markets are fairly similar in nature.

Air Canada will only go ahead with the LCC if it “is and has the ability to remain truly low cost over the longer term. It needs to be able to avoid the type of cost creep that has plagued legacy carriers over the years.” The unit would pay lower wages and have different work rules, as well as probably lower distribution costs.

The LCC unit would be specifically targeted to two types of long–haul markets: high–volume leisure–oriented routes to Europe (such as Amsterdam, Dublin, Casablanca, Nice, Lisbon and Manchester) and sun destinations in the Caribbean. It would be a growth vehicle, entering many new markets that Air Canada has not been able to serve because of its high legacy cost structure. The venture would have sufficient scale: eventually a 50–strong fleet of two types, including 20 widebody and 30 narrowbody aircraft. The widebodies would be mostly incremental and the narrowbodies would be mostly transferred from Air Canada. However, the LCC would start with something like six A319s and four 767s and grow gradually over a number of years.

One reason Air Canada would like to launch the LCC early is that, because of the 787 delivery delays, it will have many years of virtually no growth. It would not be able to bring aircraft into the fleet unless it had a “compelling business case to do that”. Yet the LCC would require only minimal capex. It would help Air Canada create a more seasonally balanced network, reduce costs and eventually help improve ROIC.

However, the financial community is not totally on board with the LCC idea, which they view as risky (in light of the poor track record of such ventures in North America and Air Canada’s lagging financial performance) and possibly adding to overcapacity in long haul international markets.

Debt, pension and cost challenges

With the completion of its fleet–wide cabin refurbishment programme and the 777 deliveries, Air Canada has very modest capital spending requirements until 2014, when the 787 deliveries start in earnest. Soit is likely to generate positive free cash flow in 2011–2013, just like it did last year (C$746m).

The good news is that Air Canada is determined to take advantage of that window and de–leverage its balance sheet a little. However, the disappointing news is that it is only looking to make its scheduled repayments, which amount to C$500m this year and C$400m in 2012, rather than pay down debt early. It remains extremely highly leveraged, with adjusted net debt of C$4.6bn as of March 31.

Of course, pension liabilities are another problem area. As a 75–year–old formerly government–owned airline, Air Canada has about C$13bn of liabilities under its defined–benefit pension plans. At the beginning of 2011, based on preliminary estimates, the pension deficit stood at C$2.1bn, which was C$600m lower than a year earlier as a result of strong fund performance.

Although the mid–2009 moratorium on pension contributions expired at the end of 2010, Air Canada’s funding obligations will be capped in 2011–2013 (amounting to only C$150m this year, for example). However, the payments will soar in 2014, so new solutions are needed. In the current contract negotiations, the management has proposed to the unions essentially two things: reducing existing employees’ future pension benefits by up to 40%, and switching new hires to defined–contribution pension plans, which do not provide a guaranteed level of payout upon retirement.

Union opposition to these changes is not surprising, given Air Canada’s improved financial position and the lucrative compensation packages earned by its top executives last year. The switch to defined–contribution plans should really have been done in bankruptcy (as at the US legacies). Then again, the proposals are in line with what many companies in North America have implemented in the past decade, and given also the new conservative political climate in Canada, Air Canada’s workers will have to accept the new reality. It is not clear if the threat of strike–busting legislation will help or hinder the labour situation at the airline.

But Air Canada’s most important task is to achieve the planned “radical cost transformation”.

It is on track to realise the C$530m CTP target by year–end, but that plan has not really helped reduce the cost disadvantage against WestJet, other LCCs and the US legacies. According to a CAPA analysis, in domestic–only comparisons WestJet’s CASM is about half of Air Canada’s. BofA ML calculated that the differential is about a penny per ASM wider than that between US legacies and LCCs.

Air Canada is working to make cost containment and reduction a permanent part of its culture (following US legacies’ example here). Also, over medium term there are cost reduction opportunities with airport fees, maintenance and aircraft ownership costs — three areas that apparently account for the majority of the ex–fuel CASM difference between Air Canada and the average US legacy. The airline hopes to cut maintenance costs when its current heavy maintenance agreement expires in 2013, and it expects to reduce ownership costs by purchasing more future aircraft.

In the past two years Air Canada has worked hard to try to improve its corporate culture – something that the CEO calls “perhaps the most important priority”. The aim is to foster a culture where “leadership, entrepreneurship and ownership are valued and rewarded”. Those efforts have included building a more transparent relationship with the unions and paying C$64m in 2010 performance rewards to employees (including C$13m in special one–time share awards to high–performing individuals).

Achieving a good culture has to be one of the toughest challenges for airlines, but Air Canada’s management has claimed that there has already been a positive shift, as indicated by improved customer satisfaction ratings and surveys showing a 20% improvement in “employee engagement”.

Of course, the pension reform proposals may have at least temporarily derailed that process.

| In Active | On | ||

| Model | Service | Order | Options |

| A319-100 | 39 | ||

| A320-200 | 37 | ||

| A321-200 | 10 | ||

| A330-300 | 8 | ||

| 767-300ER | 31 | ||

| 777-200LR | 6 | ||

| 777-300ER | 12 | 18 | |

| 787-8 | 37 | 13 | |

| E-175 LR | 15 | 15 | |

| E-190 LR/AR | 45 | 45 | |

| Total | 203 | 37 | 91 |