Air Canada: fundamentally reinvented?

November 2004

Air Canada emerged from bankruptcy protection on September 30 after an 18- month restructuring process that reduced its cost structure and significantly strengthened its balance sheet. The Montreal–based airline says that it is confident that it can compete successfully with LCCs with the help of a simplified fare structure and many new strategies, including extensive use of 70–100 seat RJs. In fact, Air Canada claims to have "fundamentally reinvented" itself — it no longer considers itself a traditional legacy carrier but a "highly connected global network carrier offering the simplicity and ease of our low–cost competitors".

When presenting the new strategies to analysts on September 27, the management was extremely bullish about Air Canada’s prospects — and there was no acknowledgement of the challenges that lie ahead.

Subsequently, on October 19, the company staged an extravagant event, with the help of superstar Celine Dion, to "present the new Air Canada to the world". The question that came to mind was: has this airline really spent the past 18 months in bankruptcy, demanding major sacrifices from employees and other stakeholders?

But matters of style aside, is there substance behind the management’s claims? Does Air Canada now have a business model that works in the new environment?

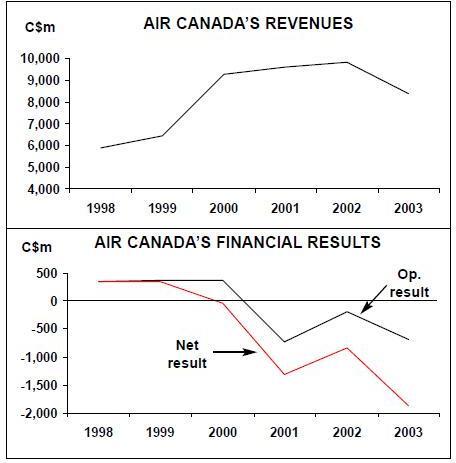

The restructuring is certainly producing some early promising financial results. After three and a half years of operating losses totalling C$1.7bn, Air Canada staged a turnaround in the third quarter. The airline estimated in mid–October that it would post a C$235m operating profit (before restructuring charges) for the three months ended September 30, following break–even in the June quarter. That would be impressive in light of the record–high fuel prices and the continued extremely weak revenue environment in North America. (Air Canada’s results will be out on November 15.)

However, the financial community is sharply divided on Air Canada’s longer–term prospects at present. Numerous Canadabased analysts started covering the company immediately after it was re–listed (at C$20) on the Toronto Stock Exchange on October 4, but the range of their initial one–year price targets is rather wide — from around C$14 to C$49.

There are three key concerns. First, the airline’s cost cutting programme may not give it a sufficiently competitive cost structure.

Second, it may not be able to retain a large–enough unit revenue (RASM) premium over LCCs. Third, there are doubts about the suitability of the RJ strategy, not helped by US Airways' second Chapter 11 filing and Independence Air’s current difficulties (though none of that can be blamed on the RJ strategies).

Of course, Air Canada will have more time to get its act together than its counterparts south of the border. First, Canada is not as competitive as the US domestic market — Air Canada still enjoys a dominant position domestically, accounting for just under 60% of traffic. Second, Air Canada benefits from a strong global network and is likely to remain Canada’s dominant long–haul international carrier for many years to come.

Successful CCAA exit

Air Canada was able to exit successfully from creditor protection under CCAA ("Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act", the Canadian equivalent of Chapter 11), first, because it secured a comprehensive restructuring agreement with General Electric Capital Corporation (GECC). In addition to restructuring aircraft leases on highly favourable terms, the deal provided for a C$540m exit–financing facility and a commitment for future RJ financing.

Second, Air Canada raised C$1.1bn in new equity capital in the restructuring.

Of that, C$850m came from a rights offering earlier this year, under which creditors swapped debt for equity (receiving about 10 cents of equity for every dollar of claims).

Subsequently, in the summer, New York private- equity firm Cerberus Capital Management agreed to purchase C$250m of convertible preferred shares in the new entity.

The result is a shareholder base dominated by former debt holders.

Cerberus has a 9.16% stake. Original shareholders hold less than 0.01% (they received one new share for 11,894 old shares in the rights offering). Because there are relatively few retail or institutional investors, trading is expected to be fairly limited. Non–Canadian holding is expected to remain small — up to 25% would be permitted.

Under the new corporate structure, ACE Aviation Holdings (ACE) is the parent company for Air Canada and other business segments.

In addition to Aeroplan (FFP), Jazz (regional division), Destina.ca (travel web site) and Touram (vacations), which were already separate legal entities, the restructuring established three new legal entities under the ACE umbrella: Air Canada Technical Services (ACTS), Air Canada Cargo and Air Canada Groundhandling. The board of ACE is led by Robert Milton as chairman and Michael Green of Cerberus as lead director.

Overall, the restructuring reduced Air Canada’s net debt and capitalised leases from C$12bn to C$5bn. The airline also exited bankruptcy with a relatively healthy cash position of C$1.9bn.

Deep enough cost cutting?

Air Canada’s cost cutting programme aims to reduce annual operating costs by C$2bn, representing a 20% reduction from 2002’s level of C$10bn, by the end of 2006.

Of the C$2bn total savings, C$900m is slated to come from labour, C$700m from aircraft rents and C$400m from other sources.

Just over half of the targeted cuts were achieved in 2003, the first full year in bankruptcy. This year’s target is C$1.5bn and next year’s is C$1.9bn. The indications are that the programme is running ahead of the original schedule.

According to Air Canada, measures are now in place that will lead to C$1bn of annual labour cost savings. C$800m of those cuts were secured in the first negotiating round in May 2003, followed by C$200m in May 2004. The unions ratified the new labour agreements in July.

The starting point was to benchmark full–service and low–cost carrier productivity.

Like the US legacy carriers, Air Canada first focused on productivity improvements, before moving to wage cuts to make up the difference. In the second round, Air Canada introduced a "B" wage scale for new hires and recalls, put in place early retirement incentives, and completed the productivity measures and "A" scale wage cuts.

Among the key mainline employee groups, pilots have had their pay reduced by 15–30%, flight attendants by 13% and mechanics by 3.9% (management and executives took 5–7.5% and 12.5–20% cuts, respectively). The airline eliminated shift premiums, longevity pay premiums, two statutory holidays and one vacation week, reduced overtime rates and lengthened progression through scale. The revised work rules meant longer duty hours, more productive shift schedules and more part–timers.

Technology benefits are now permitted. Employment security provisions have been repealed. Proportionally similar labour savings were achieved at regional unit Jazz.

Air Canada was also able to reduce pension expenses and extend the funding schedule. Also, the 24% reduction in staff numbers over the 2002 level has led to a significant labour productivity improvement, because the airline has not contracted much in size.

It has been a point of some concern that the labour contracts have a mid–point wage re–opener in 2006, meaning pay increases are possible from 2007. But Air Canada’s management has played down the impact, pointing out that productivity is not a reopener and that there is an agreement on two important issues: use of binding arbitration, if necessary, and no industrial action through 2009.

As regards to aircraft ownership costs, Air Canada claims to have secured an average annual cash rent reduction of C$711m or 49% in 2003–2009, compared to the 2002 level. While in bankruptcy, the airline rejected 48 parked or surplus aircraft, converted owned and debt–financed aircraft to operating leases and obtained significantly lower lease rates. The management believes that Air Canada obtained better lease deals than any of the US carriers (including those currently in Chapter 11) simply because of the timing — the negotiations took place in the depths of the SARS crisis, when aircraft lessors were not able to go to their usual "safety valve", Asia.

Air Canada is also targeting C$500mplus annual savings from miscellaneous sources, including restructured supplier contracts, operational changes, elimination of meals in economy class, etc. As of August, the airline had identified C$420m of such savings.

The airline has claimed that its North American units costs (CASM) have fallen "dramatically" and that the impact of the restructuring on international CASM should be even greater. However, there are no statistics to support such claims, even when fuel prices are excluded (though it is possible that some of the cost savings have so far only showed up in special items).

Looking at the latest (2Q04) unit cost figures, the progress made seems rather insignificant. Air Canada was able to report an impressive 11% year–over–year decline in CASM, from 16.4 to 14.6 Canadian cents (or a 15% decline excluding fuel), but it also grew mainline ASMs by 11%. In the year earlier period, from 2Q02 to 2Q03, CASM actually rose by 7%, but mainline capacity fell by 18%. So the two–year CASM decline was only 4.6%, as the airline contracted in size by 9.4%. Total operating costs (excluding restructuring) were reduced by 15.8% in the two–year period.

The problem is that the C$2bn overall annual cost reduction may not be enough to make Air Canada competitive with LCCs.

The current CASM gap with WestJet, its main low–cost competitor, is still around 3.5 Canadian cents (almost 3 US cents).

This is a larger gap than what most of the US legacy carriers now have relative to LCCs. It is probably also larger than US Airways' infamous 4–cent gap when differences in average stage lengths are taken into account — Air Canada’s is about 1,300 miles, compared to WestJet’s 790 miles. Air Canada’s 14.6–Canadian cent CASM (around 12 US cents) seems very high for a long–haul carrier, even after allowing for higher Canadian cost levels. However, as a dominant airline domestically, with lucrative international routes, it has much more breathing space than US Airways did.

Revenue considerations

The key consideration for Air Canada, like other legacy–type, full service airlines, is whether its unit revenue (RASM) premium over LCCs will be sufficient to offset the remaining CASM disadvantage.

Air Canada’s top executives said that the airline has experienced similar RASM premiums over LCCs in its hubs than the US legacy carriers.

The difference seems to be that while most US carriers now take the view that those premiums will erode over time, Air Canada is counting on being able to maintain its current RASM premiums. That may not be realistic.

The airline believes that it can maintain the RASM premiums, first, by "maintaining frequency superiority" in domestic markets and, second, by "having happy customers".

Frequency superiority will be maintained by increased use of smaller, 70–90 seat aircraft. The management noted that LCCs would continue using larger than 100–seat aircraft and predicted that Air Canada would achieve higher load factors.

That is an unusual way of looking at things. Usually, smaller aircraft are chosen because they are the right size for thinner routes. An airline may want to expand into smaller markets (JetBlue, for example) or retain a presence in such markets (US Airways). Aircraft in the 70–90 seat category — with the possible exception of the EMB–190 — are not meant for head–to–head competition with 150–seaters. Whatever RASM or load factor benefit there might be would be more than offset by the CASM disadvantage.

Strategies aimed at making customers happy have probably more potential, and Air Canada has accomplished much in that regard. Most significantly, it has introduced a simplified fare structure that "allows for better understanding of value" and makes it easier for customers to choose the fare that best suits their needs.

The pricing strategy was first revised in May 2003 by narrowing 22 or so domestic fare types into just six categories. Last month the airline eliminated one of those categories (Econo), along with minimum stay and round trip requirements for fares on all continental North America flights. It now has five simple fare types — Tango, Fun, Latitude, Freedom and Executive Class. The fare types are priced according to the built–in benefits in terms of flexibility, refundability, level of FFP mileage accumulation, lounge access, etc.

The Tango fares represent an expansion of Air Canada’s domestic Tango operation.

As the management described it: "We've basically taken Tango to the world as our low–fare product". The level and structure of those fares have been made the same as WestJet’s.

Gaining customer trust is considered to be the key challenge with the Tango fares, meaning that customers must know that they will not find a lower fare in the marketplace than the one Air Canada is offering.

Air Canada has developed a simple way of showing the five fare types on a single page on its web site.

Air Canada has evidently focused hard on what value propositions could be put into the different fare types, and the management indicated that the process is far from complete.

However, US experience has shown that it is extremely difficult for legacy carriers to overhaul their fare structures without an overall negative impact on revenues.

Once the key restrictions on the lowest fares have been abolished (to make them competitive with LCC offerings), it is hard to convince customers that there is truly value in paying more for another fare type.

Air Canada says that it is encouraged by the response to the new fares and that "quite a few people" are paying for the extra value.

However, it has so far declined to provide any figures or even rough estimates on how many people are flying at the higher fares or which way the business mix is changing.

The airline says that customers are still learning about the business model.

The airline unveiled what it described as a "contemporary new look" last month — an updated design and colour scheme for the fleet (to be implemented over the next two years) and new uniforms for front–line staff. It is also adding seat–back entertainment systems for all aircraft except 50–seaters from May 2005 and lie–flat seats for international business class from September 2005.

Air Canada describes its new business model as being based on "simplicity, flexibility and efficiency in all areas of our operations".

The newly redesigned web site is a "focal point for a number of strategies", facilitating both cost savings and product change. Online sales as percentage of revenues are currently in the high 20s, up from just 2% in 2000, though over 60% domestically.

The target by 2006 for Canada is 92%,Canada–US 65% and other international 40%.

Route network strategy

Air Canada has a global network, with Canada accounting for 43%, Canada–US 23%, transatlantic 21% and other international 13% of total revenues in 2003. North America’s share has declined by almost five percentage points in the past two years, as revenues in that region plummeted by 21% between 2001 and 2003. European routes have seen a corresponding increase, with revenues rising by 5.2%.

The vision for the restructured Air Canada is "to be the customer’s clear choice in domestic and transborder markets by offering mass transit/self–service product and to leverage its global network as their preferred carrier for travel".

For the North American markets, that means high–frequency service between all major cities and maximum connectivity with smaller aircraft. In settling on that strategy, Air Canada was motivated by the benefit of being a dominant carrier in a hub, particularly in respect of RASM premiums. An analysis of selected US markets by Seabury Group, using DoT statistics, found that the number one carrier in terms of market share also got more than its "fair share" of revenues. The second and third largest carriers under–performed in terms of revenues.

In other words, the study suggested that rank in a city is a primary determinant of expected RASM premium.

In respect of future growth, however, the focus of Air Canada’s post–bankruptcy strategy is on international markets outside North America. The airline ranks as the 13th largest international carrier in the world, serving 19 countries in the Americas, seven in Europe and six in Asia. In addition to benefiting from Star alliance membership, it enjoys unfettered access to parts of the world that US carriers cannot serve.

After being sidetracked by the 1999 acquisition of Canadian and delayed by the post- September 11 crisis and its own bankruptcy, the airline is now ready to start adding new international destinations from various Canadian gateways. Its top executives predict that Air Canada’s international operations could eventually far outweigh its domestic service.

The executives said that Air Canada would probably begin looking for niche markets not served by other international carriers, such as the recently introduced nonstop Toronto–Delhi route. There is obviously good potential to draw traffic from the US market for such services.

Subsequently, late last month Air Canada announced plans to launch the first–ever nonstop flights between Vancouver and Sydney in mid–December, operating two daily flights with 282–seat A340–300s.

The airline sees further opportunities from Vancouver to markets across the Pacific, as well as over the pole to destinations such as Delhi.

The airline also recently introduced nonstop Toronto–Hong Kong A340 service, which has been successful. It sees further opportunities from Toronto particularly to China and Korea.

Air Canada also sees some growth opportunities to secondary markets in Europe — in the first place, it will reintroduce service that was terminated in the wake of the SARS crisis. There are also further opportunities in Latin America, into which Air Canada has been pushing successfully since the US government’s introduction of a "transit without visa" programme.

Air Canada welcomed transport minister Jean Lapierre’s late–October announcement that the government would consider liberalising Canada’s air policies, including lifting foreign ownership restrictions on airlines.

Fleet plans

Air Canada has reduced its fleet by 13% in the past two years, from 336 aircraft in early 2003 to 293 aircraft at the end of this year, including 197 at mainline and 96 at Jazz. The plan is to continue phasing out older widebody aircraft and to introduce up to 180 new 70–100 seaters. There will be a need to add long–haul aircraft at some point — the current thinking is that it will be possible to find used 767–300s, A330s and A340s. The airline took the 70–100 seat decision after realising that its narrowbody fleet was significantly over–gauged — 63% of total block hours flown carried fewer than 100 passengers per flight, while only 29% of block hours were operated by aircraft with less than 120 seats. Another factor was the availability of new–generation small jets that have attractive economics and high customer appeal, such as the EMB–190, which JetBlue will introduce from mid–2005.

Immediately after emerging from bankruptcy, Air Canada placed orders for up to 180 new 70–90 seat aircraft, dividing the commitment equally between Bombardier and Embraer. First, there was a firm order for 15 CRJ200s and 15 CRJ700s, plus 15 conditional orders and 45 options, with the 50–seat deliveries beginning immediately (last month) and the 70–seat deliveries in May 2005. Next, Air Canada ordered 45 EMB–190s plus 45 options, for delivery from November 2005.

As a result, Air Canada’s RJ fleet will rise from just 35 aircraft at the end of 2003 to 68 by year–end 2005 and 124 by year–end 2007. The CRJs will be split equally between mainline and Jazz, to comply with the pilot scope clause, while the EMB–190s will be flown by mainline pilots. The management said that all of the aircraft would be introduced at totally competitive pay rates, with pilot costs on the EMB–190 being "within striking distance of JetBlue's"

Outlook

Air Canada believes that it is now well positioned to generate operating profits, and analysts generally agree with that, at least for the near term. A profit in the third quarter (October–December) will be in sharp contrast with the worsening losses reported by most US airlines.

While yields remain weak in Canada and the US routes, they are improving in many other international markets. Thanks to higher overall system traffic and yield, Air Canada expects to report 12% revenue growth and 6% higher RASM in the third quarter. Even though fuel prices remain a concern, fuel surcharges in effect for Canada–US and all international travel and a stronger Canadian dollar have helped mitigate the impact.

| Mainline | |||||

| Year-End Fleet | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 |

| A319 | 48 | 48 | 47 | 46 | 46 |

| A320 | 52 | 50 | 47 | 45 | 40 |

| A321 | 10 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| A333 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| A343 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| B737 | 10 | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| B747-CMBI | 3 | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| B767 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 7 |

| B767-300 | 26 | 30 | 30 | 29 | 29 |

| CRJ 200 | 25 | 25 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| EMB 190 | - | - | 3 | 20 | 44 |

| 70-100 seats | - | - | - | 15 | 15 |

| Total Mainline | 197 | 197 | 191 | 196 | 213 |

| jazz system | |||||

| CRJ 200 | 10 | 22 | 28 | 50 | 50 |

| DH1 | 36 | 45 | 42 | 40 | 34 |

| DH3 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| B142 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRJ 705 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Total jazz | 82 | 96 | 111 | 131 | 125 |

| Total ACE | 279 | 293 | 302 | 327 | 338 |

| Total RJs | 35 | 47 | 68 | 100 | 124 |