US industry: At last profits return

June 2006

In the spring of 2004, when crude oil prices had hit the mid–to–high $30s per–barrel range (a level that now sounds utopian) and the US legacy carriers were headed for a fourth consecutive year of heavy losses, the consensus opinion was that the long overdue US airline industry consolidation process was imminent. Experts predicted that, through mergers or liquidations, the number of large network carriers would whittle down from six to three or four. The June 2004 issue of Aviation Strategy covered this subject in an article titled "US legacy carriers: shakeout to begin this autumn?"

But even though oil prices have since then doubled, exceeding $70 per barrel in recent months, the shakeout never happened. There has been only a single liquidation — FLYI, the parent of Independence Air, in early 2006 — and only one merger, between US Airways and America West in 2005.

Independence Air was a rather special case; the ex–regional failed because it could not make its unusual new LCC model — an independent hub operation at Washington Dulles and a fleet of primarily 50- seat RJs — work in the competitive East Coast environment. The airline was too small to have much positive impact on industry capacity when it disappeared, and there is little chance of a resurrection because the operating certificate has been sold to Northwest’s new regional subsidiary Compass Airlines.

US Airways and America West, in turn, pulled off what can only be described as a miracle — an intelligent, well–funded and well–executed merger that created a new type of "hybrid LCC". The old US Airways used the Chapter 11 bankruptcy process to rationalise its fleet and reduce its high legacy labour costs to effectively LCC levels, transforming itself into an attractive merger target (see Aviation Strategy, December 2005). The new AWA–managed entity is reporting strong results and is on the "buy" list of every analyst. However, there remain significant labour integration challenges, the outcome of which may not be clear until early 2007. US Airways contributed meaningfully to the industry capacity reduction by removing 59 aircraft or 15% of its fleet through the merger and choosing not to grow over the next couple of years. If the integration is successful, the merger could provide a blueprint for future deals.

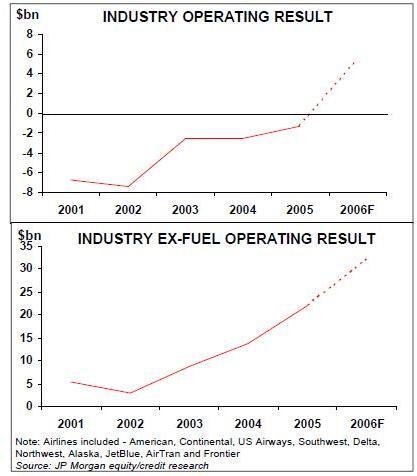

The industry shakeout has not happened because, amazing as it seems, the US legacy carriers are staging a financial recovery despite crude oil prices remaining around $70 per barrel. The US airline industry is expected to return to profitability in the current (second) quarter; Merrill Lynch’s mid–June estimate was an aggregate net profit of around $600m for the three–month period (excluding Delta and Northwest, which are in Chapter 11, but including the main LCCs).

After five years of heavy losses, the industry is also poised to report a net profit for 2006; the current estimate from Calyon Securities is "over $400m". Of the solvent carriers, only United and JetBlue are expected to report losses for the year. Excluding fuel, the US airline industry is actually currently achieving record operating profits. In other words, without the past three years' hike in oil prices, this would be a boom year for airlines.

Former UBS airline analyst Sam Buttrick (now at the bank’s Fundamental Investment Group) noted in a speech in early May that the US airline industry was "structurally, meaningfully profitable at $60 oil", adding that he was impressed that the industry had adapted in a relatively short period of time to a significant negative shock. The recovery trend has been reflected in airline stocks. As at mid–June, the Amex Airline Index had risen by 27% since its low point in late September 2005. Airlines such as American, Continental, Alaska and US Airways continue to be on the "buy" lists of most analysts.

"Who would ever have thought that we would be recommending stocks with fuel prices at $70 a barrel?" marvelled Mesa’s CFO Peter Murnane at Merrill Lynch’s annual transportation conference in mid–June. "It is unbelievable."

New capacity discipline

Of course, none of this is surprising outside the US, where many airlines have remained profitable in the current fuel environment thanks to their ability to pass on increased fuel costs to customers. Until recently that was not the case in the US domestic market, where the competitive dynamics are such that no airline with a sizeable presence on a route dares charge higher fares than competitors for risk of losing market share. For many years it was difficult to get fare increases to stick, and the problem was exacerbated by the increased presence of LCCs and excess capacity (which Continental’s CEO estimated at 25% in mid–2004). The legacy carriers had no domestic pricing power.

However, unexpectedly large capacity cuts by US Airways in its second Chapter 11 visit last year and by Delta and Northwest soon after they went into Chapter 11 in September 2005, together with a highly disciplined approach by the solvent carriers (except Continental), have removed much of the excess capacity from the domestic market.

Domestic industry capacity (ASMs) is expected to decline by 2% this year, which analysts say will be the first–ever instance of domestic shrinkage in a non–recessionary environment, except for September 11. (Of course, airlines outside the US will not derive comfort from the knowledge that much of that capacity will shift to international markets.) The strongest of the legacies, American, has reiterated that it cannot grow until it reaches profitability; the airline is shrinking its domestic mainline capacity by 4% this year, as it grows international ASMs also by 4%. By contrast, Continental is sticking to plans to grow by 5–7% annually in the next few years, with the 2006 rate being even higher, justifying it by the need to provide feed to international routes (read: wanting to capture market share).

Of course, many LCCs continue to add capacity in double–digits.

The magnitude of the legacies' domestic shrinkage is best illustrated using pre- September 11 as the baseline. According to JP Morgan data, between 2000 and 2006, Delta, United, US Airways, American and Northwest reduced their domestic capacity by 28%, 24%, 23%, 23% and 22%, respectively.

The tight capacity situation, combined with strong demand particularly this spring and summer, has led to a dramatically improved domestic revenue environment — a trend that began in the autumn of 2005. There have been numerous fare increases and most of them have stuck. Domestic mainline unit revenue (RASM) growth in the first half of 2006 has been running in double–digits, with May seeing a 15.1% increase.

These positive domestic revenue trends are expected to continue, given the constrained supply, strong summer bookings and a new Delta–led $50 business fare increase put in place in mid–June. Also, there is some way to go to full recovery — the May RASM was still 20% below the 2000 peak.

As a result, as Merrill Lynch analyst Mike Linenberg pointed out in a recent report, top line growth is now more than offsetting rising fuel costs; this happened in the first quarter and is likely to continue through 2006. The legacies' results are also benefiting from continued efforts to reduce non–fuel costs — after five years of heavy cost cutting, it is amazing that the airlines are still finding potential targets (other than through Chapter 11).

American, for example, is trying to reduce its costs by another $1bn this year, needed just to keep expenses in line with 2005 levels; the airline has identified $700m of those cuts through measures such as fuel conservation and lowering distribution costs.

American’s improved prospects received an important acknowledgement in the form of a June credit ratings upgrade by Standard & Poor’s (from "B–minus" to "B"). The agency concluded that better revenue generation and ongoing cost cutting efforts had more than offset the effect of high fuel prices. S&P also noted that AMR raised $400m in a public share offering in May and had an ample $4.3bn in available cash.

Industry liquidity remains strong, with Continental (as in the past) being the black sheep in that regard with cash reserves of less than 20% of annual revenues. JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker suggested in a recent report that "only above $80 crude should investors start to fret about liquidity, and then only about CAL". However, the legacy balance sheets are expected to benefit from pension reform and/or continued access to the public equity market.

Continental recently announced plans to monetise more of its 27.3% stake in Panama’s Copa in a public offering.

All the indications are that if the positive revenue trends continue and there is excess cash, it will be used to repair balance sheets rather than make acquisitions.

Consolidation later?

At UBS’s annual transportation structured debt conference in early May, two very different views on where the US legacies’ direction in terms of consolidation, were presented.

UBS’s Sam Buttrick, while noting the dramatic improvement in legacy profitability, argued that structural issues dictated that "consolidation among large network carriers is close at hand", and that his best guess is the second quarter of 2007. Buttrick made the point that the US legacy sector is a "chronically oversupplied business" that does not need six or seven carriers pursuing the same plan (hub–and–spoke operations). "Business combinations would be a blaringly obvious solution"; yet, unlike in other industries, there has not been a merger between healthy sizeable carriers for two decades (since USAir/Piedmont in the mid–1980s).

Buttrick noted the many valid reasons why there have not been mergers, including labour integration problems, regulatory issues, lack of management resolve, mediocre track record of past mergers and the existence of "synthetic" substitutes such as code–sharing. However, he noted potential positive developments on the labour and regulatory fronts. US Airways' ability to successfully integrate the labour forces could set an important precedent.

And a well–crafted merger plan may now be more favourably received by regulators.

As Buttrick pointed out, the fact that the third and fourth largest airlines (Delta and Northwest) are in bankruptcy obviously heightens the possibility of mergers in the future.In contrast, Avitas' SVP Adam Pilarski said that he did not see additional bankruptcies or consolidation because of the substantial capacity cuts already accomplished by four legacy carriers in Chapter 11. He made the point that since 2000 United, US Airways, Delta and Northwest have seen their combined market share fall from 50.5% to 41.6%. That voluntary capacity reduction was similar to the 10.1% capacity share removed when Pan Am and Eastern ceased operations in the early 1990s — the last major industry shakeout. As Pilarski put it, "there does not have to be bloodshed".

Furthermore, Pilarski did not buy the overcapacity argument, particularly since load factors were at record highs. "You don’t have overcapacity, you have wrong airline pricing." Both Buttrick’s and Pilarski’s predictions seem plausible, depending on circumstances. If the industry recovery continues and/or US Airways fails in its integration efforts ,there may not be consolidation. But if the industry recovery falters, through a demand downturn or excessive capacity addition, and/or US Airways succeeds, there may well be mergers.

If US Airways succeeds, it may encourage consolidation along the lines of nimble smaller carriers doing reverse merger type transactions with the legacies, as CEO Doug Parker has predicted. Importantly, the US Airways/AWA deal demonstrated that outside capital is readily available to fund solid and innovative business plans.

Another possibility, in the wake of US Airways/AWA, is that there will be opportunistic mergers or cooperation among the smaller carriers. Calyon Securities analyst Ray Neidl has suggested that Frontier, which is being squeezed in its Denver home base by United and Southwest, needs more market mass and would be a good fit with JetBlue, which has also indicated that it is now open to cooperative deals. The two business models have similarities in terms of equipment type, in–flight service and culture, and the route systems would be complementary.

But such deals would not solve structural problems such as reduce the number of hubs, which many Wall Street analysts believe will hit the industry in the next economic downturn at the latest. Consequently, speculation persists about a potential Delta/Northwest combination. United/Continental is also mentioned regularly, while American apparently does not believe that it is out of the picture either.

It would seem that, for the current year at least, both Delta and Northwest are too busy getting their own houses in order. While investors are reportedly eagerly awaiting any opportunity to participate in merger transactions involving those airlines, analysts such as Neidl take the realistic view that, even though the route systems are complementary, the DoJ is not yet ready to allow such larger mergers.