US Airways/America West: "Full-service, low-cost, low-fare"?

December 2005

US Airways and America West closed a merger transaction on September 27 that pulled US Airways out of Chapter 11 bankruptcy and created an AWA–managed nationwide carrier described as the "first full–service, low–cost, low–fare airline".

The deal was notable for its speedy completion, for raising a staggering $1.7bn in new equity investment and partner support and for its initial unenthusiastic reception by Wall Street analysts. How did the airlines manage to persuade savvy investors to part with their money, given the difficult industry environment and dismal history of large airline mergers in the US? How will they meet the challenge of labour integration? Is the new US Airways a likely long–term survivor? Under the "reverse merger" type transaction, which took only four months to complete since it was announced on May 19, America West Holdings (the acquirer) became a wholly owned subsidiary of US Airways Group and will give up its name. The reorganised company began trading on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) on September 27 under the symbol "LCC".

US Airways and America West plan to fly on separate operating certificates for up to two years, with their own maintenance and training regimes, while employee seniority and labour contracts are sorted out.

However, the airlines are already code–sharing, have combined their FFPs and airport clubs and expect to have combined operations at most of their 38 common–use airports by year–end. The plan is to roll out completely new branding and eliminate the AWA name in the first quarter and have a single web site by April. Combining reservations systems is likely to take until early 2007.

The deal offered a lot to AWA. Its shareholders received the largest single stake in the new entity (37%); the rest was divided between outside investors who provided financing (52%) and US Airways' unsecured creditors (12%). AWA also received the largest number of board positions: six out of 13, with US Airways designating four directors and outside investors taking up three positions. AWA’s chairman/CEO, Doug Parker, took over at the helm of the new US Airways, whose management team is made up of roughly two–thirds AWA and one–third US Airways executives. The reorganised company is based at AWA’s headquarters in Tempe, Arizona.

In supporting the deal, AWA’s controlling shareholder TPG Partners and the company’s board were swayed by the argument that the merger would enhance AWA’s long term strategic position. Even though AWA was already a low–cost carrier — it had always had low costs and since 2001 had also transitioned to an LCC–style simple low–fare structure — its geographically limited, leisure oriented network posed a hurdle to long–term survival as a stand–alone entity. The deal with US Airways offered something AWA had coveted for years: access to the higher–yield East Coast.

US Airways' general shareholders received nothing in the transaction, having seen their shares wiped out in Chapter 11.

While secured creditors recovered 100% of their claims, unsecured creditors recovered only 3–17%. Special deals were negotiated with the ATSB, GE Capital and Airbus. Retirement Systems of Alabama (RSE), which financed US Airways' first Chapter 11 reorganisation in 2002–2003, lost its entire $240m investment, though the merger facilitated a graceful exit for RSE’s chairman David Bronner. US Airways' CEO/president Bruce Lakefield, who worked closely with Doug Parker to push the merger through, is serving as vice–chairman/board director of the new entity.

For US Airways, the deal provided a new lease on life. Although the airline did reduce debt and improve liquidity in Chapter 11, even succeeding in substantially reducing labour costs and lining up new equity funding, it was struggling to come up with an acceptable business plan in the high fuel cost environment. Many in the industry had expected US Airways to liquidate in its second stay in bankruptcy protection.

This was probably the key to getting the merger approved on the US Airways side — it was the airline’s last chance. Nevertheless, it was a major accomplishment that the parties managed to persuade everyone that the deal was worth doing.

Industry experts have attributed the success of the transaction to the fact that the airlines had a clear plan, that they acted quickly and that they avoided labour trouble at the outset.

Parker’s vision, proven track record and presentation skills must have also played a part. Aged 43, he has been described as "smart, energetic and eager". He has presented the new entity very effectively as a new type of "hybrid LCC", an airline of the future that will be copied by others.

This airline has all of the prerequisites for survival: a strong cash position, a robust business plan, a low cost structure and a strong network. As Parker bragged at Wing’s Club in September: "No–one has been able to come up with this amount of capital, cost structure and route network" and that "this airline has staying power".

As Parker has frequently pointed out, two things happened that were critical to getting the merger completed and which will also help make the new entity successful. The first was Chapter 11, which enabled US Airways to get the right cost structure and eliminate key differentials with AWA. Second, the substantial additional financings, equity investments and partner support were vitally important, giving US Airways strong cash reserves.

Chapter 11 was the key

US Airways ended up in Chapter 11 again in September 2004 largely because during its first reorganisation it had failed to sufficiently anticipate the growth of LCC competition in its markets. Consequently, in its second Chapter 11 the airline focused on and succeeded in reducing its high legacy labour costs to effectively LCC levels. This was done by renegotiating union contracts, to obtain further concessions, and by terminating defined benefit pension plans for the flight attendants and machinists in January 2005 (following the termination of the pilots' plan in the first Chapter 11). Overall, the two Chapter 11 visits reduced labour, pension and benefit costs by around $2bn annually.

The labour cost savings were in addition to cost savings achieved in Chapter 11 through cutting overheads, including reducing management payroll, by renegotiating various contractual obligations and by rationalising the fleet.

Chapter 11 transformed US Airways into an attractive — or at least lower–risk — merger target for AWA. While removing aircraft and capacity made possible to avoid duplication and permitted synergies, having similar labour costs will help smooth workforce integration. As Parker explained in a recent presentation, "the bankruptcy process allows things to happen that will be friendly to consolidation.

The history of the airlines' dealings, outlined in prospectuses and SEC filings, illustrate how important Chapter 11 was in paving the way for the merger. US Airways and America West first held discussions and undertook due diligence in February–July 2004, but those talks concluded that "a number of issues, particularly related to labour, pension and benefit costs, made a merger impracticable". The talks were revived five months later "in anticipation of US Airways' success in significantly reducing its labour costs", following its second Chapter 11 filing.

The airlines also noted in December 2004 that the bankruptcy gave US Airways "greater flexibility to combine its network with AWA’s network in a more efficient and cost effective manner" and that the improved liquidity would also help a potential combination.

Negotiations on a merger resumed in earnest in January 2005, resulting in the May 19 agreement.

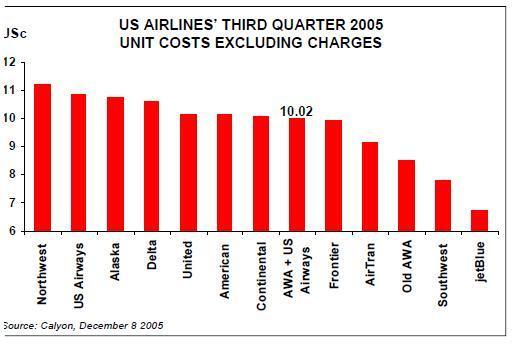

The new US Airways will obviously not have unit costs rivaling those of JetBlue, Southwest and AirTran. Analysts such as Merrill Lynch’s Mike Linenberg and JPMorgan’s Jamie Baker have estimated that its CASM will be in the middle of the pack — lower than those of most legacy carriers but higher than most LCCs'.

New funding and partner support

The merger was possible only thanks to substantial new investment and financial assistance from a multitude of parties in the context of the Chapter 11 reorganisation.

After attracting $867m in new equity financing and another $830m in partner support, US Airways had an ample $2.6bn in cash (of which $1.7bn was unrestricted) at the end of October. This was about 25% of annualised revenues — at the high end of the industry range, with only Southwest, JetBlue and AirTran having better cash positions. The reserves should enable US Airways to avoid a cash crisis even if fuel prices stay high through 2006.

However, as the credit rating agencies have pointed out, US Airways remains highly leveraged, with a debt load of about $3.5bn, or over $9bn including operating leases. The lease–adjusted debt–to–capital ratio of 95% is in line with legacy ratios but much higher than the mid–70s typical for LCCs (or Southwest’s 40%). On the positive side, total leverage will fall modestly as the leased fleet shrinks further, but debt maturities will still be significant in 2007–2009.

In summary, US Airways benefited from the following new equity investments, partner support and other transactions in connection with the Chapter 11 exit and the completion of the merger:

- New equity funding The total of $867m in new equity, which is the largest amount of new equity ever raised by a US airline, far exceeded the $375m stipulated by the merger agreement. The funds came from four established investment firms (Wellington, PAR, Tudor and Peninsula) and two airline partners (ACE and Air Wisconsin), as well as a September public share offering that raised $180m.

- Convertible debt offering In late September US Airways also raised $139m in net proceeds from a private placement of senior convertible notes due in 2020.

- Payments from credit card partner Under a new agreement signed in August, AWA’s credit card partner Juniper Bank made a $130m bonus payment and pre–purchased another $325m worth of miles from US Airways, in return for becoming the exclusive co–branded credit card provider for the merged entity.

Loans from Airbus Airbus provided US Airways two loans totalling $250m, in addition to rescheduling deliveries and promising additional backstop financing for A350s.

- Sale/leaseback transactions US Airways received $125m in additional support, primarily from aircraft lessors, in the form of sale/leaseback transactions involving various Airbus aircraft.

- Agreement with GE Capital Under a complex deal, GE Capital agreed to retire US Airways' bridge loan facility, buy and lease back 21 aircraft and engines, allow $28m new borrowings, restructure 59 leases to market rates, provide financing for current and growth aircraft and waive certain penalties.

In return, US Airways paid GE $125m in cash, accepted certain modified leases and returned early 51 aircraft and engines.

- Asset sales to Republic US Airways raised $100m from the sale of Embraer RJs and airport slots to Republic Airways, its regional partner. Republic purchased or assumed the leases of 28 E170s and will continue to operate them for US Airways.

- Restructuring of ATSB loan guarantees The ATSB has been highly accommodating to US Airways, allowing the airline to continue using the cash collateral that secured the government–guaranteed loan while in Chapter 11 and in July promptly approving the merger transaction. In September new terms were negotiated for US Airways' and AWA’s ATSB–backed loans, which at that time totalled $832m. The loans were kept separate, with different repayment schedules and interest rates, but new requirements were introduced about using proceeds from asset sales to pay down the debt.

Subsequently, in late October, the loans were sold to fixed–income investors, meaning that the ATSB no longer has an interest in US Airways' debt.

- Deal with the PBGC The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), which has been trustee for US Airways' three terminated defined benefit pension plans since February 2005, reached a settlement with US Airways on its claims that totalled $2.7bn. Under the deal, the PBGC received $13.5m in cash, a $10m unsecured promissory note and an ownership stake in the reorganised carrier.

The latter amounts to 4.9m shares, representing 70% of the common stock allocated to unsecured creditors.

A "hybrid LCC"?

The US Airways/AWA combination is not really aiming for anything new with its "hybrid" legacy/LCC product and market strategy, because LCCs in the US have moved further and further away from the traditional Southwest model. For example, many LCCs now use both point–to–point and hub models, operate to both secondary and primary airports, operate more than one aircraft type, have FFPs and in many cases provide a higher quality and better service than the legacy carriers. However, the new US Airways is clearly a few notches closer to the legacy type than existing LCCs.

The new entity offers a combination of premium amenities not available on other LCCs, including a global FFP, airport clubs, assigned seating, first class cabin and the hourly US Airways Shuttle between Boston, New York and Washington. The aim is to provide "excellent value" with a "competitive, simplified pricing structure", essentially replicating the fare structure that AWA put in place in March 2002. Merrill Lynch’s Linenberg suggested that the brand could be characterised as "business casual".

US Airways will stand apart from other LCCs because of its scale — it will be the fifth largest domestic airline, with a truly nationwide network — and because of its international franchise. The airline offers on–line service to 44 destinations in Europe, the Caribbean, Mexico and Canada, plus nearly 800 destinations in 139 countries through the Star Alliance. The airline will continue to operate hubs in Charlotte, Phoenix and Philadelphia, with secondary hubs or focus cities in Las Vegas, Pittsburgh, Boston, New York LaGuardia and Washington Reagan National. Two wholly owned subsidiaries operating as US Airways Express will continue to feed into the hubs.

The airline expects all of that to differentiate its service from other LCCs, allow it to strengthen customer loyalty and attract new traffic. It may succeed, but it is worth bearing in mind that, as Southwest and JetBlue have demonstrated, real success in the marketplace for LCCs is the result of hard–to–replicate factors such as great leadership, strong corporate culture and high employee morale.

Parker is highly regarded both in the industry and on Wall Street, having led AWA’s transformation since 2001. The key tenets of his management philosophy seem exemplary — diligent cost control, an analytical approach to revenue management, operational integrity and employee focus.

However, he will have the enormously challenging task of combining two very different corporate cultures and implementing the merger without adverse effects on employee morale.

Merger synergies

In early December US Airways estimated that it would incur about $300m in one–time costs related to the merger over two years, including information systems, severance, training, aircraft painting and configuration and other transition expenses. About $90m of the total will have been spent by year–end, with the remainder to be spent mainly in 2006.

However, those costs would be handsomely offset by the merger synergies, which the airline predicts will build up to $600m annually by 2007. This figure has been criticised as over–optimistic, given all the uncertainty in the competitive environment; however, the sharper than expected capacity cuts by competitors on the East Coast in 2006 have, for the moment at least, made that figure look more achievable.

The $600m annual synergy total would be made up of $250m cost savings, $175m cost savings or revenue enhancements resulting from fleet and route restructuring and $175m revenue synergies. The cost savings, which look likely to be achieved in full, include a reduction in the administrative overhead, in–sourcing of information technology and combining facilities. US Airways has eliminated 31% of management positions at director level and above and will close the old Crystal City headquarters by April.

The $175m fleet/route–related synergies will come from right–sizing the total fleet, eliminating unprofitable flying, down–gauging aircraft to better meet demand and adding Hawaii service. Specifically, US Airways is parking 60–plus mainline aircraft in the near term, rejecting expensive leases and replacing more 737 flying with 70–seat and 90–seat RJs.

Hawaii is a strong, relatively high–yield leisure market that has proved attractive to many airlines in recent years, including the Southwest/ATA code–share alliance. US Airways introduced the first phase of its Hawaii expansion in mid–December: daily 757–200 flights linking Phoenix with Honolulu and Kahului. A second phase, introducing service from Las Vegas and more destinations and frequencies from Phoenix, will follow in March.

The $175m revenue synergies are envisaged through enhanced city presence, improved connectivity and better asset utilisation. This is the most questionable category, because it essentially assumes a market share shift from competitors. Then again, the East and West route networks are so nicely complementary that one would expect there to be revenue benefits through improved connectivity.

Much will depend on who the future competitors are. Merrill Lynch’s Linenberg made the point in a recent research note that while Independence Air’s shrinkage at Washington–Dulles and possible liquidation in early 2006 is obviously a major positive for US Airways, it could quickly turn into a negative if, say, JetBlue started to build a position at Dulles. Linenberg said that his 2007 forecast gave US Airways credit for only half of the targeted $175m revenue synergies.

The integration challenge

US Airways' biggest challenge over the next two years will be labour integration — the stumbling block in many past airline mergers.

Seniority issues, always tough to resolve, pose a particular hurdle for these airlines because old–established US Airways has a much more senior workforce than 22–year old America West, and America West is the acquirer.

There are two mitigating factors. First, two of the key groups — the pilots and the flight attendants — are represented by the same unions, which have established procedures for integrating seniority lists.

Second, some of the contracts and wage levels are apparently fairly similar. In JPMorgan analyst Jamie Baker’s estimates, mechanics' wage rates are nearly identical, while pilots' wage rates are within about $10 per hour of each.

However, US Airways' management has conceded in recent speeches that addressing issues of pilot seniority has been a difficult task. There are no obvious solutions.

On the positive side, the two airlines reached a transition agreement with their respective ALPA–represented pilot groups in mid–September that will govern merger–related aspects of their relationships until there is a single collective bargaining agreement.

Negotiations on a combined contract kicked off in mid–November, with the somewhat ominous message coming from the pilot groups that they had mapped out a strategy and it involved getting their fair share of the rewards arising from the merger synergies.

US Airways has also reached transition agreements with several of its smaller unions, most recently with the communications Workers of America (CWA) and the Teamsters, which represent passenger service employees.

The management is counting on the workers bearing in mind that the merger means lasting job security for a large number of employees. Morale among the old US Airways workforce, which earlier this year was at an all–time low after repeated concessions, pension plan terminations, job losses and liquidation fears, has evidently improved in recent months.

Labour integration may be further complicated by the two companies' vastly different cultures, with US Airways having a typical staid, businesslike East Coast culture and AWA a more relaxed West Coast, Southwest–style fun culture. Among various measures, the merged entity has appointed a "VP of culture".

Aside from the labour issues, the integration of systems, processes and facilities are all challenging tasks. If not expertly executed, they can lead to higher costs or customer service problems.

Growth and financial prospects

To its credit, US Airways has not only removed 59 aircraft or 15% of its fleet through the merger but has chosen not to grow over the next couple of years, preferring instead to focus all of its efforts on integration.

This is admirable and likely to pay off financially, though the company’s share price may suffer.

As a plus point, all of the 59 aircraft being removed are apparently leaving North America, which means that US Airways will have contributed meaningfully to the industry capacity reduction.

US Airways expects to operate a 361- strong mainline fleet in 2006 — 198 A319/320/321s, 100 737s, 44 757s, ten 767s and nine A330s — plus 241 RJs and 112 turboprops. This compares with 411 mainline aircraft operated by the two airlines at the end of June.

Although the merged airline is taking a few AWA–ordered A320s by February, the A320s and A330–200s that the old US Airways had on order will now not arrive until 2009–2010. To rationalise international flying, the airline will begin transitioning to an all- A350 fleet in 2011; a firm order for 20 A350s was signed at the end of November. On the regional front, US Airways already operates 38 90–seat RJs and plans to grow that fleet while shrinking its 50–seat fleet.

The company recently reiterated its original early–summer projection that it will be profitable in 2006 excluding one–time merger- related costs. Wall Street analysts, who generally did not agree with that 2–3 months ago, now accept it more. The current consensus estimate is a loss of 6 cents per share — effectively a break–even — before one–time items in 2006, with the forecasts ranging from a loss of $2 to a profit of $2.80.

Somewhat confusingly, the current profit forecast was made when the crude oil price was only about $47 a barrel. By September, when oil had surged to the high–60s, the forecast looked out of date, even though US Airways insisted that the revenue environment had improved enough to compensate.

In the past couple of months, as the industry capacity cuts have gathered pace, unit revenues have surged and oil prices have moderated, the original forecast again looks realistic. US Airways has recorded double–digit RASM growth in recent months, well exceeding the industry average. The consensus now is that it is uniquely well positioned to benefit from competitors' capacity cuts in the East Coast. In the longer term, however, there remains considerable uncertainty.

Could Southwest and JetBlue make serious trouble in US Airways' markets? And what will be Virgin America’s impact in the West?

| America | ||

| US Airways | West | |

| Passengers (2004, 000s) | 42,400 | 21,119 |

| Pax Load factor | 75.1% | 77.4% |

| Revenue (2004, $m) | 5,482 | 2,327 |

| Net result | -611 | -87.6 |

| Yield/RPM (US cents) | 12.5 | 7.7 |

| Cost/ASM (US cents) | 10.8 | 7.8 |

| Pay/employee ($) | 79,240 | 51,503 |

| Av. Aircraft utilisation (hrs per day) | 9.4 | 10.9 |

| Av. stage length (miles) | 782 | 1,053 |

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | |

| Transition costs* (total | |||

| $300m) | (90) | (210) | 0 |

| Ramp-up of synergies | |||

| Route | 0 | 175 | 175 |

| Revenue | 22 | 132 | 175 |

| Cost | 18 | 186 | 250 |

| Total | 40 | 493 | 600 |

| TOTAL BENEFIT (COST) | (50) | 284 | 600 |

| US AIRWAYS | AMERICA WEST | |||

| In fleet | On order | In fleet | On order | |

| A318 | 15 | |||

| A319 | 57 | 34 | 8 | |

| A320 | 24 | 6 | 57 | 10 |

| A321 | 28 | 13 | ||

| A330 | 9 | 10 | ||

| A350 | 20 | |||

| 737-300 | 60 | 35 | ||

| 737-400 | 43 | |||

| 757-200 | 31 | 13 | ||

| 767-200 | 10 | |||

| Total | 262 | 49 | 139 | 33 |