Air Canada: Resurgent and aggressive

Jul/Aug 2005

When ACE Aviation Holdings, the parent of Air Canada, emerged from an 18–month bankruptcy restructuring in September 2004 with reduced costs and a greatly strengthened balance sheet, its near–term financial recovery prospects looked promising.

However, the financial community was sharply divided on Air Canada’s longer–term prospects — the key concerns were that its cost structure might not be competitive enough and that it might not be able to retain a large–enough unit revenue premium over LCCs (see Aviation Strategy, November 2004).

Nine months on, while the longer–term concerns are still there, Air Canada is in the middle of staging a remarkable financial recovery. Why is it able to go against the North American industry trend and turn profitable in this environment?

Air Canada has also made several aggressive or unusual moves in recent months — the sort of moves that one would not expect from a carrier that emerged from bankruptcy less than a year ago.

First, Air Canada has announced plans to make a US$75m equity investment in merged US Airways–America West.

How can it possibly justify such a move? Second, Air Canada has placed a spectacular US$15bn order for up to 96 Boeing 777s and 787s and, equally stunningly, cancelled it when its pilots failed to ratify a tentative agreement on rates and terms for flying the aircraft. Was the order really cancelled, and if so, what are the repercussions for strategy?

Third, in April ACE raised over C$1bn in new liquidity through concurrent equity and convertible note offerings and by obtaining a new C$300m credit facility.

Fourth, at the end of June, ACE spun off in an initial public offering (IPO) 12.5% of its Aeroplan FFP, collecting C$125m in net proceeds (or C$160m if the over–allotment option is exercised fully). This was the first–ever monetisation of an airline FFP.

Although some of the proceeds raised in April were used to refinance debt, the result has been improved cash reserves.

If Air Canada continues to monetise its various business units, which seems likely, it may have the rather nice problem of deciding what to do with excess cash. It seemed so surreal when, at a time when other large North American carriers worry about liquidity, ACE chairman/CEO Robert Milton mentioned the possibility of dividends at Merrill Lynch’s recent transportation conference.

Profitability on the horizon

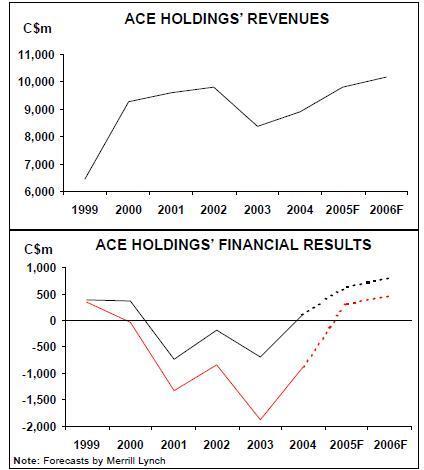

After three and a half years of operating losses totalling C$1.73bn (US$1.41bn), ACE staged a turnaround in the third quarter of last year, posting a C$243m (US$199m) operating profit for the period. This was followed by a break–even result in the fourth quarter. For the full year, the company reported a modest C$117m (US$96m) operating profit (1.3% of revenues) and a reduced C$880m (US$721m) net loss, which was almost entirely made up of reorganisation charges.

ACE did well to achieve near break–even operating results in the first quarter of 2005 — the result actually improved by C$135m year–over–year, despite a C$77m higher fuel bill. Excluding hedging benefits, ACE was the only North American carrier to report improved results for the quarter.

With its cost cutting programme on track and an improving revenue picture, ACE is expected to start posting quarterly operating profits and achieve a net profit in 2005.

Merrill Lynch analyst Mike Linenberg forecasts that ACE will earn operating and net profits of C$638m and C$323m, respectively, in 2005, followed by C$802m and C$462m in 2006. The operating margins (6.5% and 7.9%) would be similar to those achieved by the successful North American LCCs.

ACE’s results are exceeding expectations essentially because progress on the revenue side (rather than on the non–fuel cost side) has been much better than anticipated.

The company’s cost–cutting programme aims to reduce annual operating expenses by C$2bn, representing a 20% reduction from 2002’s level of C$10bn, by the end of 2006. Of the C$2bn total savings, C$900m is slated to come from labour (mainly through productivity improvements), C$600m from aircraft rents (already achieved) and C$500m from other sources (see Aviation Strategy, November 2004).

In the past couple of quarters, the cost savings have begun to show up more in ACE’s unit cost (CASM) figures. Non–fuel CASM is now running about 20% below the levels two years earlier, which is quite impressive.

Nevertheless, the C$2bn overall annual cost reduction will not make Air Canada’s cost structure competitive with LCCs.

Last year, analysts estimated that the CASM gap with WestJet, the main low–cost competitor, was around 3 US cents — more than the differential between most of the US legacy carriers and LCCs.

Air Canada now openly admits that it is not getting close to LCCs' cost levels. Milton called the restructured airline simply "lower–cost", proclaiming that it has transformed itself from a "legacy" to a "loyalty carrier".

Air Canada has benefited enormously from the simplified domestic fare structure that it introduced in May 2003 and extended to its US network in February 2004. The fare structure "allows for better understanding of value" and makes it easier for customers to choose the fare that best suits their needs.

A key part of this strategy is the concept that Tango, the low–fare product, "will not be undersold". Air Canada matches all of its competitors' lowest fares. The strategy has helped the airline achieve its goals of regaining customer trust and building loyalty.

Also, because Air Canada does not initiate discounting (it merely matches fares), there have been instances of competitors adopting more sensible pricing.

As an indicator of the success of the new pricing strategy, Air Canada has built a significant domestic load factor premium over WestJet since early 2004. In recent months the premium has been as high as 6.5–7.5 points. (Air Canada obviously also enjoys a domestic RASM premium over WestJet and other LCCs, because it offers business class, FFP, etc.)

Otherwise, low–cost carrier Jetgo’s departure (March 11) has significantly improved the domestic revenue environment.

WestJet noted recently that fares in Canada have not been this stable for 20–25 years. Both WestJet and Air Canada have been able to cautiously increase their fares to offset the fuel price hikes.

Jetsgo had 7% and 5% domestic and trans–border market shares, respectively.

Milton said at the ML conference that while Air Canada had expected to capture most of the transborder share, he was pleasantly surprised at how much of the domestic share it picked up too.

As a result of all that, Air Canada has been achieving record load factors for 16 consecutive months. In June it had 81.2% and 81.3% domestic and system passenger load factors, respectively.

The most striking thing about these trends is that Air Canada appears to be gaining at the expense of LCCs.

The opposite is the case in the US and European markets, where LCCs as a group are gaining market share and the best of the carriers are also capturing higher–yield traffic from the legacy airlines.

The Canadian situation may have something to do with the fact that none of the LCCs there are particularly strong — WestJet, while an important player with a 27% domestic capacity share, is not of the Southwest/JetBlue calibre. However, above all, the situation reflects Air Canada’s dominance in all market areas.

Air Canada is not only the dominant domestic operator, with a 55% ASM share, but it also has 40% of the transborder market and 45% of the long–haul international market. It controls regional feed with its subsidiary Jazz, which is Canada’s second largest airline. Because it does not have to share the domestic market with other large carriers, it has been able to build Aeroplan into a uniquely strong FFP. Also, Air Canada has virtual monopoly of the country’s international traffic rights.

Unlocking the value of business units

The bankruptcy restructuring slashed ACE’s net debt and capitalised leases from C$12bn to C$5bn and gave the company cash reserves of C$1.9bn. The cash position was relatively healthy (21% of last year’s revenues), but the debt was still on the high side. Furthermore, the liabilities included an expensive C$540m exit–financing facility provided by GE Capital.

Consequently, in March ACE sought to raise about C$600m through new share and debt offerings to refinance the GE facility.

As things turned out, investor demand was so strong that the company was able to boost the offerings to C$792m (including over–allotments). In addition, ACE obtained a new C$300m two–year secured revolving credit facility for general corporate purposes.

After the transactions were completed in April, ACE had net debt and capital leases of C$4bn, cash of C$2.1bn (exceeding its target of C$2bn) and an unused credit line of C$300m. The refinancing of the GE facility cut annual interest costs by C$27m.

ACE then turned its attention to its business units, announcing plans for its first partial spin–off. At the end of June, it took Aeroplan public as an income trust, selling a 14.4% stake and listing it on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The sale raised gross proceeds of C$287.5m (including over–allotments).

ACE collected about C$160m; the rest was retained by Aeroplan for a reserve for FFP mile redemptions and for capital expenditures. The IPO valued Aeroplan at C$2bn, which was above the earlier predictions of C$1.3–1.9bn.

Aeroplan was the first of what is expected to be many partial spin–offs.

The consensus view is that Air Canada Technical Services (ACTS) is the next in line, followed by regional carrier Air Canada Jazz.

ACTS is a full–service MRO organisation and a "centre of excellence" for Airbus, Bombardier airframes and GE engines. It has 100–plus global customers (including JetBlue, United, Lufthansa and ILFC) and enough capacity to significantly grow third–party work without major capital investments.

Earlier this year it secured a new five–year US$300m maintenance contract with Delta. But what really makes ACTS the hottest spin–off candidate is that it will pull in a large contract with US Airways–AWA as part of ACE’s planned investment in the merged carrier.

This is all part of a strategy to enhance shareholder value, as well as obviously ensure that Air Canada can fund fleet renewal and expansion. ACE’s likely goal is to be an aviation holding company with majority stakes in a number of thriving businesses.

Planned investment in UAIR/AWA

The planned US$75m investment in US Airways/AWA, announced on May 19, will give ACE an ownership stake of less than 7%. The investment will be made only if/when US Airways emerges from Chapter 11 (currently expected this autumn).

Furthermore, Air Canada expects the investment to pay back fully in less than two years.

The investment is conditioned on commercial agreements in areas such as maintenance, ground handling and RJ flying, so it makes sense in the context of ACE’s broader business strategy of growing its business units into stand–alone profitable companies.

The biggest beneficiary will be ACTS, which will pull in a new five–year maintenance contract worth C$1.5bn in revenues.

As a result, ACTS will become one of the world’s largest MRO companies, with C$1bn annual revenues by 2006. ACE also expects to benefit from maintenance and ground handling synergies to the tune of C$65m annually. It is also likely to gain access to better slots and gate selections at airports such as New York LaGuardia, Boston Logan and Phoenix.

There would appear to be promising revenue opportunities because the route networks are highly complementary.

Air Canada sees such opportunities in key trans–border markets to southwestern US, Hawaii, Mexico and Florida.

The deal could also strengthen its relatively weak presence along the North American West Coast. And Air Canada could pull significant volumes of traffic from the US Airways/AWA network to its international services out of Toronto and Vancouver.

ACE said initially that the US Airways deal would complement its existing relationship with United, which provides Air Canada with a strong east–west presence through Chicago and Denver. When asked about this at the ML conference, Milton was rather more specific: "There is absolutely no question: our primary US partner is United". Of course, Air Canada and United have incentive to help US Airways because all three are members of the Star alliance, which would lose out if US Airways failed. If the deal goes through, Star would benefit from the inclusion of AWA’s network in western US.

North American RJ strategy

Air Canada aims to defend its domestic and trans–border market shares by offering a high–frequency "mass transit schedule" between key cities and deploying regional carrier Jazz to fill the network. That means extensive reliance on small aircraft.

To facilitate that strategy, immediately after emerging from bankruptcy Air Canada placed orders for up to 180 new 70–90 seat jet aircraft, dividing the commitment equally between Bombardier and Embraer.

The orders were for three RJ types: the Bombardier CRJ–705, Embraer E170 and Embraer E190 (15, 15 and 45 firm orders, respectively). Jazz will operate all of ACE’s Bombardier aircraft, while Air Canada will fly all of the Embraers.

This is a critical time for the RJ strategy because deliveries of each of the three types begin this year. Jazz started taking delivery of the 75–seat CRJ–705s in late May and will receive up to three per month by December, enabling it to boost its summer schedule across the country.

Air Canada will receive its first E175s this month (July), while the E190 deliveries will begin in November.

The CRJ–705 is apparently getting "rave reviews" from customers, which is perhaps not surprising given that in many cases those aircraft are replacing Dash–8 turboprop service.

Air Canada’s top executives have called each of the three aircraft types "a game–changer" both in terms of product offering and economics. That may be the case with the product offering — they will all be flown in two classes, with 34–37 inches of legroom, leather seats and (from this autumn) in–seat audio and TV systems. While only the E190 has the look and feel of a small jet, they are all clearly much more passenger–friendly than the 50–seat RJs.

However, while JetBlue has convinced the world that the E190, which it will start receiving in August, can more than match 150–seat economics (at the right pilot pay rates), it is hard to see how the 70–seaters could compete successfully against legacy carriers' 737s and A320s. If ACE’s 70–seat strategy works, it may only be because of its market dominance and because Canada and US–Canada are not as competitive as the US domestic market.

All of the aircraft are well suited to ACE’s plans to serve more long–haul thinner markets nonstop. The new aircraft are expected to create many new trans–border route opportunities, such as linking Toronto, Montreal, Halifax and Ottawa with new points in Florida and Texas, and East Canada hubs with points in California and Arizona.

Air Canada will fly the E190s under all new pilot contracts. The management said last year that the aircraft would be introduced at totally competitive pay rates, which will be "within striking distance of JetBlue's".

Focus on international growth

But the main focus of Air Canada’s post bankruptcy strategy is on international markets outside North America. The airline ranks as the 13th largest international carrier in the world, operating a well–balanced global network as it enjoys unfettered access to parts of the world that US carriers cannot serve. Its Toronto and Vancouver gateways are well positioned to serve US to Europe and Asia traffic. It has a wealth of unused international route rights, because it was earlier sidetracked by the 1999 acquisition of Canadian and then delayed by the post–September 11 crisis and its own bankruptcy.

Furthermore, Air Canada’s international services are highly profitable, because fares in those markets have remained high and because the international unit cost cuts have been the sharpest. ACE’s top executives claim that Air Canada’s international CASM is now among the lowest in the world, with the possible exception of the mainline China carriers.

Last year saw much Latin American expansion, partly because of the significant opportunity offered by the US "no transit without a visa" policy, which has made transiting via Canada an increasingly attractive option.

The other initial strategy was to look for niche markets not served by other international carriers. New route additions in that category included Toronto–Delhi and Vancouver–Sydney last year.

Otherwise, the focus is on building nonstop service to Asia particularly from Toronto, even though Vancouver remains the main Asian gateway. Last year Air Canada introduced Toronto–Hong Kong A340 service, and this summer it has added Toronto–Beijing and Toronto–Seoul.

The airline now operates 13 daily flights from Canada to eight Asian cities.

The biggest immediate growth opportunity is China, following a more liberal new ASA signed in April. Air Canada’s plans call for a Toronto–Shanghai nonstop service next summer, increase to daily flights on Toronto–Beijing by 2006, Vancouver- Guangzhou from summer 2007 and new freighter services to China from 2007.

Late last year the thinking at Air Canada was that it would be possible to find used 767–300s, A330s and A340s to accommodate international growth in the coming years, and the airline subsequently found six widebody aircraft to add to the fleet this summer. Now, after the Boeing order debacle,

Air Canada has at least temporarily returned to the strategy of acquiring used aircraft.

The widebody renewal plan that Air Canada presented to the world with great fanfare in late April — and which it still may return to — included up to 36 777s and up to 60 787s. Those two types would have eventually replaced the entire long–haul fleet, including the A330s and A340s.

They seemed uniquely well suited to Air Canada’s route structure and plans, in that they offered different seating capacities (to suit different sized markets or seasonal demand fluctuations), yet the same speed and range. The order was for 18 777s (plus 18 purchase rights) in a yet–to–be–determined mix of 300ERs, 200LRs and freighters, and for 14 787s (plus 46 options and purchase rights). Deliveries of the 777 were set to begin in 2006 (first three aircraft) and the 787s from 2010.

Air Canada cancelled the order on June 18 after its pilots rejected a tentative agreement on costs and other issues that had been reached with union leaders on June 8.

The order had been conditional on the pilot deal, so there was no penalty. The airline would have had to pay a nonrefundable US$200m deposit to Boeing on June 19 to keep the order.

The cancellation is not material to Air Canada’s business plan over the next few years — the critical components were the 787s slated for delivery from 2010 to replace the 767 fleet. The airline merely stated that "in time we will re–address this requirement", though Air Canada president/ CEO Montie Brewer also expressed hope that it would be possible to bring new aircraft into the fleet.

The pilot vote apparently reflected an unrelated longstanding dispute over seniority that stemmed from the merger with Canadian. It therefore seems odd that the management simply accepted the vote — allowing a pilot protest to dictate fleet strategy in such a major way — or that Boeing would not have given more time to resolve the problem.

Consequently, many people believe that Air Canada hopes to revive the Boeing order and that negotiations are continuing behind the scenes. Air Canada might lose the earliest 787 delivery positions — Boeing said recently that the type, which has so far attracted orders from 17 other carriers (including Continental and Northwest in the US) and will be available from 2008, is "essentially sold out through 2010".

Also, it is not certain that Air Canada could keep the extra–special price that it negotiated with Boeing when competition with Airbus was particularly intense. Milton said at that time that he was confident nobody had ever done better on a deal.

Airbus is probably not seriously back in the running for new orders from Air Canada, because the airline rejected the A350 as too large and because fuel efficiency was one major factor swaying the decision in favour of twin–engine aircraft.

Then again, if Air Canada cannot negotiate satisfactory contracts for new aircraft types, in the end it could be forced to order types covered by existing contracts.

Credit considerations are a factor in the current environment. American, for example, said last month that it is unlikely to order the 787 until it returns to profitability and can get better credit terms. Dominion Bond Rating Service, when recently raising Air Canada’s outlook to "positive", urged the airline to exercise prudence in major investment decisions. The Canadian rating agency mentioned ACE’s still–significant debt, growing competition and other challenges.

Then again, the Boeing order would have given Air Canada a real lead over other North American international operators in terms of cost efficiency and ability to expand globally. With the strong cash position and further prospects for spin–offs, it is a pity that the management could not risk paying the US$200m deposit to Boeing without a specific pilot contract in hand.