Qantas: Ultra long haul

Project Sunrise

Jan/Feb 2020

Australia is a wonderful country. The world’s smallest continent and largest island, it has been described as a traveller’s paradise: home to some of the quirkiest wildlife, coral reefs, picturesque rain forests, red-earthed national parks, stunning beaches, and scorching deserts.

But is is also a very long way from anywhere.

There are very strong cultural links with the UK, the historic colonising power (the two countries still share a Head of State). And Qantas, the national flag carrier naturally has pursued the politically sensitive aim of providing links with the “mother” country half way round the world.

Qantas initiated (and trade-marked) the first “Kangaroo route” service between Sydney and London in 1947: 29 passengers and 11 crew in a Lockheed Constellation with stops in Darwin, Singapore, Calcutta, Karachi, Cairo and Tripoli. It took four days (and cost £585) to cover the 19,200km.

Current widebody aircraft can now easily do the route with just one stop. However, this has meant that it is still open to significant competition from carriers based at hubs vaguely intermediate, with connecting flights on offer through Singapore, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, Taipei, Chengdu in Asia; Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Doha in the Arabian Gulf; and even going the other way round the world through Los Angeles could be attractive.

However, airlines based at the ends of such an ultra long haul route are at a distinct competitive disadvantage: they have to fill up their aircraft with O&D passengers who want to go the full distance or to the intermediate stop, and have to compete against those that can afford to undercut fares to attract marginal traffic on connecting services.

Qantas and British Airways are now the only two airlines operating through routes (not involving a change of aircraft) between Europe and Australia after Virgin Atlantic closed its loss-making service six years ago. The other two major European network carrier groups — Air France-KLM and Lufthansa Group — stopped flying there in the late 1990s.

Transformation

Qantas went through an extremely difficult period after the global financial crisis, with its flagship Qantas International operations turning in significant annual losses. At one point it looked as if it might even have considered withdrawing entirely from very long haul flying entirely to stem these losses and concentrate on the growth opportunities it had created in Asia through its low cost brand Jetstar.

But then in 2013 it instigated a major “Transformation Programme” to return the group to sustainable profitability and improve earnings by A$2bn. It cut 15% of its workforce (5,000 jobs), restructured its network, significantly improved productivity and disposed of unwanted assets.

Unfortunately, the organisational restructure which involved splitting the “old” Qantas into separate operating units — QF Domestic, QF International and QF Cargo — led to an accounting writedown (accelerated depreciation, restructuring costs and operational unit goodwill) and the group reported a statutory net loss of A$2.8bn for the financial year ended June 2014.

On long haul operations it severed its long-standing joint service agreement with British Airways on routes to Europe (which to all accounts hadn’t been that profitable), switching to a comprehensive alliance with old enemy Emirates: services on the Kangaroo route would stop in Dubai allowing connections onto all Emirates services into Europe while Qantas only retained a through-route A380 service to London. It signed a deep code-share agreement with China Eastern for routes through Shanghai. It tried to get an anti-trust agreement for a joint venture with American on the Pacific (finally approved in June 2019).

This restructuring worked — helped by a certain relaxation of inbound competitor growth and increasing capacity “discipline” in the domestic Australian market. (For the financially-challenged competitor position see last month’s article on Virgin Australia). For the last five financial years Qantas has increased total group capacity by an average annual 1.3% but traffic has grown by 3% and load factors improved by five percentage points to 84%. Importantly for its strategic aim to provide returns to shareholders it achieved a return on invested capital of around 20% in each of the past four years, dipping only slightly to 19.2% in the year to end June 2019 — well above its cost of capital.

This stability has extended so far into the current financial year. In its first half results statement, Qantas announced a 2.8% growth in revenues to A$8.3bn on the back of flat capacity in ASK terms, a modest 0.7% increase in demand in revenue passenger kilometres and a 2.8% increase in unit revenues. Unit costs were well contained, despite a small 1% increase in fuel prices and underlying operating profits were much on a par with the prior year levels at A$900m — giving an operating margin of 10.8% and a rolling annual RoIC of 19.6%.

Within the group numbers, the QF Domestic operations saw a 3% fall in first half operating profits to A$464m on the back of flat capacity and a modest 1% growth in unit revenues. The Jetstar Group suffered a little on the domestic operations from weak leisure demand, and took a $12m hit from strike action, but increased capacity by 4% on its international operations. Revenues were up by 4% but operating profits down by 13% to A$220m representing a margin of 10.4%. Qantas Loyalty produced a record first half result with revenues up by 8%, frequent flier membership increasing by 5% to 13.2m, and operating margins nudging up by nearly 1 point to 22.5% giving underlying operating profits of A$192m 12% higher than the prior year level on a like-for-like basis.

Qantas International meanwhile improved earnings (by 2.5% to A$122m) despite trimming capacity by 1.5%, a $65m hit from troubles in the Hong Kong and freight markets, and modest increase in fuel costs. Here the restructuring programme is starting bear fruit: Qantas expanded its 787-9 fleet from eight to 11 aircraft (it has another three on order) and disposed of one of its ancient 747s (the remaining five are expected to leave the fleet in 2020).

The company has strong ambitions. At the November 2019 investor day, CEO Alan Joyce highlighted that the transformation programme had so far provided results improvements of an annualised A$3bn, but that programmes in place gave optimism to be able to achieve further profit enhancements of over A$400m a year, and the group has targets to double operating profits over the next three years: by 2024 it hopes to achieve operating margins around 18% at QF Domestic and 22% at Jetstar Domestic; a return on capital of over 15% at Jetstar International and over 10% at QF International; stable earnings growth at Qantas Loyalty to between A$500m and A$600m.

Kangaroo Route profitable at last

One of the more interesting comments at the investor day was that the Kangaroo Route had at last become profitable for the first time in a decade. A major reason behind this was concentrating through-routes to Europe via Singapore, where Qantas' subsidiary Jetstar Asia is the second largest LCC and provides increasing feed at the hub. Routes through Dubai are left to its code-sharing agreement with Emirates.

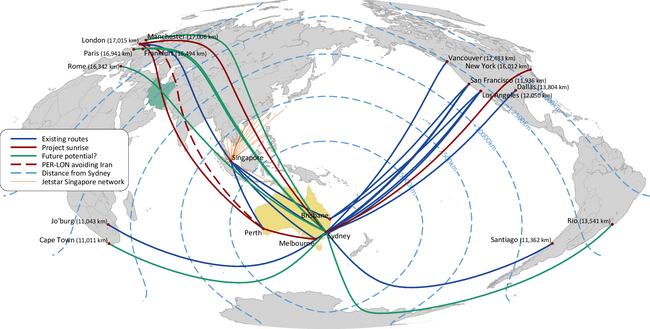

Another was the introduction of direct services between Perth and London using low density 787-9 aircraft (236 seats — 42 lie-flat business class, 28 in premium economy, with 38" seat pitch, and 166 in the back of the bus). This route is hailed as the second longest air route in the world (after Qatar’s operation between Doha and Auckland) with a great circle distance of 14,500km and travel times of 16-17 hours and is at the extreme of the 787’s maximum range. Unfortunately at the moment restrictions on overflying Iran make the route a little longer (by 100km) and may impose limitations on load.

Qantas has found that passengers are willing to pay a distinct premium for a direct non-stop service (it actually operates the flight from Melbourne tagged via Perth to London) of around 30% against one-stop services. It boasts that it is achieving an extraordinary 94% load factor on the route (and a 99% load factor in business class).

Our own, unscientific testing of current pricing seems to suggest that the passenger is willing to pay an even higher premium of up to 100% (see table) — putting a business passenger’s concept of the monetary value of time at around A$500 (US$330) per hour to save four hours from a 20+ hour journey.

Not everybody would like to be stuck in a plane for that length of time. And Qantas will probably have to redesign the standard operating procedure for in-flight services (meal after take-off, go to sleep, breakfast on arrival). One on-line blogger posted a review of the Perth-London flight in economy pointing out that the length of the flight meant that he was left alone for twelve hours, but was only offered two drinks and, depressingly (because of the flight timings) it was dark all the way. He praised it as the longest flight in the world without seeing any daylight.

The success of the Perth-London route has led the company to pursue its “Project Sunrise” — developing ultra-long-haul routes between Australia, Europe and the USA. The ultimate desire is to link Sydney direct to London — a great circle distance of over 17,000km — but Qantas has also suggested that it will be looking at serving New York (a mere 16,000km).

But these ultra long-haul routes add a complexity to operations. They are expensive to run — not least because of the need to carry so much extra fuel to carry all the fuel needed to reach the destination safely (which may result in payload restrictions). There are also crewing concerns relating to duty hours and complements. For a daily operation they will require a dedication of at least four aircraft per route. Whatever happens, these routes can only make commercial sense if they have a high level of premium demand.

In the last quarter of 2019 Qantas successfully conducted a handful of research flights (rerouted ferry-flights on delivery of new 787-9s from Seattle) with 40 people on board to test ways to improve well-being of passengers and crew on ultra long-haul flights. It has been in negotiation with the unions to discuss rostering and pay — supposedly without a huge amount of success yet. It has also selected the A350-1000XWB as its preferred aircraft. It will take the final decision to pursue an order of around ten aircraft by the end of March 2020.

Meanwhile, if Qantas does go ahead with Project Sunrise it will need to find reasonable routes to operate. In the presentations at the investor day it seemed to suggest that it would look at Sydney to Cape Town and Buenos Aires. These are not necessarily “ultra” long haul but do present their own complications for direct routings over Antarctica (where there are not a lot of airports to comply with EROPS).

In the chart we show a series of routes identified by anna.aero in their assessment of the potential of unserved direct routes from Australia through analysis of the schedules and searches. It may not be surprising that London features in the top four, and that these are from each of the four cities in Australia: London has the highest level of pure O&D long-haul traffic of any international hub. Paris and Frankfurt are there, although these may be more difficult to justify on commercial viability grounds: Paris has half the level of O&D traffic on long haul routes compared with London and Frankfurt half that of Paris. Surprising entries are Beirut and Rome, which are unlikely to satisfy requirements for a high level of premium demand, and the latter would require circuitous routings to avoid the currently challenged Iranian airspace.

Alan Joyce describes Project Sunrise and the pursuit of ultra long-haul travel as the ultimate remaining aviation challenge. It is a brave challenge — to connect the antipodes by direct flights. But the problem is that this is a niche market. And niche markets in aviation have a habit of disappearing.

| Qantas | Jetstar | Total | On order | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 717 | 20 | 20 | ||

| 737-800 | 75 | 75 | ||

| 747-400 | 5 | 5 | ||

| 787 | 11 | 11 | 22 | 3 |

| A320 | 3 | 112 | 115 | 45 |

| A321 | 8 | 8 | 54 | |

| A330 | 28 | 28 | ||

| A380 | 12 | 12 | ||

| Dash 8 | 49 | 49 | ||

| F70/100 | 17 | 17 | ||

| Total | 220 | 131 | 351 | 102 |

| A$ | Business | Premium Economy | Economy | Flight time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | 7,718 | 3,716 | 1,297 | 16:45-17:45 |

| 1 Stop | 4,007 | 2,063 | 816 | 20:00-25:00 |

| 2+ Stop | 3,039 | 3,681 | 866 | 25:00-30:00 |

Notes: cheapest available t+30, return +30. † currently half an hour longer to avoid Iranian airspace.

Source: anna.aero