What is Virgin Atlantic's

Delta?

December 2017

Does the Virgin Group’s sale of a 31% stake in Virgin Atlantic earlier this year signify nothing more than Richard Branson’s latest retreat from his once-held vision of a global Virgin airline empire — or was it brilliant timing?

In calendar 2016, Virgin Atlantic (which also includes tour operator Virgin Holidays) saw revenue fall by 3.3% to £2,7bn, thanks entirely to a 4.8% reduction in revenue from airline traffic and cargo operations, to £2,2bn. This was on the back of a 2.5% year-on-year decline in seat capacity (in ASK terms), stable passenger demand (down by only 0.1% in RPK terms) and a near two point improvement in load factors to 78.7%.

Underlying operating profits nevertheless improved by 75% to £39.8m from £22.5m a year before (albeit a paltry 1.5% margin) as unit revenues fell by 1% year on year, slightly lower than the 1.1% fall in unit costs (despite a 17% reduction in fuel costs). The company stated that the devaluation of Sterling against the US Dollar following the British referendum vote to leave the EU also impacted the business by more than £50m.

The group does not implement hedge accounting policies. As a result its fuel and currency hedges are treated as derivative trading (as if it were a commodity broking business) and are marked to market at period end and passed through the profit and loss account. Between 2015 and 2016 there was a huge swing in the fair valuations of derivative contracts. In 2015 the airline took a £139.7m hit from these contracts, but in 2016 it benefitted to the tune of a £74.7m gain on derivatives. That’s a £214.4m net swing year-on-year. Officially, operating profits in the period fell from £178m to £153m and published statutory net profits jumped from £87.5m tp £232m.

In 2016 cargo revenue fell 15.9% — again thanks to overcapacity in the market — and cargo yield fell by 17.2%. But one bit of good news in 2016 was Virgin Holidays, which has changed its distribution to 100% direct sales. Last year it sold 341,000 holidays (to punters who travelled to more than 45 destinations) and the unit more than doubled its profit before tax and exceptional items, to £19.1m.

Comparisons of Virgin Atlantic’s accounts between years are problematic. This is partly because it is a private company (with relatively little detail given until very recently). In 2013 it changed its financial year end to December from February (influence from Delta?). Also, until 2015 the airline prepared its financial results under the UK’s GAAP accounting rules (which it could legitimately do as it is not a listed company), rather than under the international financial reporting standards (IFRS).

Nevertheless, Virgin Atlantic posted its third consecutive year of profit in 2016 under IFRs standards (after Virgin restated its 2014 results under that standard for the first time). In the ten years to end 2013 the group appears to have lost £295m at the operating level on revenues of £21.7bn — a negative margin of -1.3%.

Looking more closely at the figures, however, uncovers some worrying trends. Passengers carried in 2016 fell by a stunning 0.5m to 5.44m (see chart), though overall load factor rose by 1.9% to 78.7% as capacity was cut back (ASKs fell 2.5% year-on-year). However, passenger yields fell by 3.4% and unit revenues by 1% in 2016 (see chart) due to “a combination of lower fuel prices being passed on to customers and supply/demand imbalance leading to market fare reductions”.

The net profit after exceptional items of £187m in 2016 allowed the group to post a positive equity position of £23m at the end of the year up from a negative £(164)m a year before (albeit including intangible assets — a capitalisation of its route network — of £164m).

The majority of the fleet is under operating leases (with only three 747s and two 787s owned), and the group had a net cash position on balance sheet of £90m at the end of Dec 2016 (down from £198m in the prior year), with long-term debt rising by £99.3m in a year, to £462.8m as at the end of 2016.

At the end of 2015 Virgin successfully issued a highly innovative £220m bond secured on its Heathrow slots — it is the third largest operator at the constrained London airport behind BA and Aer Lingus with 3% of the total.

As at the end of 2016 Virgin Atlantic’s cash liquidity stood at £551.2m (20% of revenues) — barely changed from £561.2m as of 12 months earlier. Net debt including capitalised leases (using a 12% cap rate) grew from £1.5bn to more than £1.6bn as at the end of 2016 — a debt/equity ratio of 7,000%.

Plan to Win

Virgin Atlantic has been trying to change. 2017 is the third year of a four-year business plan called Plan to Win, which “will deliver long-term success” according to Craig Kreeger, the CEO of Virgin Atlantic. Among its objectives are a “relentless focus on costs” that has saved £60m and with an expected another £50m of savings in 2017 — and revenue improvements. Earlier this year Kreeger admitted Virgin Atlantic was facing “increased capacity from low-fare, long-haul competitors… we are focussing on remaining true to who we are — a full service carrier”.

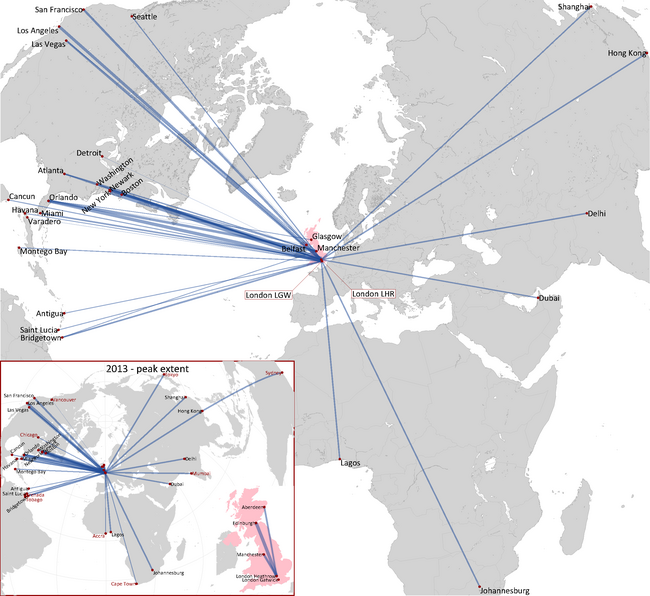

Virgin Atlantic currently operates to 30 non-stop destinations, comprising eleven in the US, eight in the Caribbean and Mexico, six elsewhere in the world (Delhi, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Dubai, Johannesburg and Lagos), and five UK airports.

All 11 US destinations in Virgin Atlantic’s network are served out of one or other of its two London hubs, but seven of these destinations compete against Norwegian Air routes out of London Gatwick — to Las Vegas, Los Angeles, San Francisco (Oakland for Norwegian), Seattle, Boston, Newark and JFK. And seven London Virgin Atlantic routes also compete against Wow Air out of London Gatwick, via Reykjavik, to Boston, Newark, JFK, Miami, Washington, Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Around 70% of all Virgin Atlantic’s revenue comes from its transatlantic routes (and 72% is sourced in the UK), and rising LCC competition shows why it was so important for Virgin Atlantic to tie itself closer to Delta Air Lines. It derives substantial benefit from its joint venture with Delta on transatlantic routes (2016 was the third full year of partnership, following Delta’s purchase of Singapore Airlines’ 49% stake in Virgin Atlantic for £224m in June 2013). Delta co-located all its London flights with Virgin Atlantic at Heathrow Terminal 3 in 2016, and the partnership offers more than 220 connecting destinations across more than 630 routes, with 39 peak flights from the UK to the UK every day on the JV (and with 1,500+ passengers connecting between the two airlines daily). Outside of London though, there’s less traction between Delta and Virgin Atlantic, as the latter’s routes out of Glasgow and Belfast are seasonal leisure destinations, while Manchester is split between leisure and business routes.

Since Delta’s investment it is apparent that Virgin has become more financially oriented towards profitability (Delta officially cannot be seen to control, but its representatives can no doubt provide advice). The company went through a full review of all its routes and discovered, perhaps unsurprisingly, that those to the West (US and Caribbean) and to restricted destinations such as Lagos and maybe Hong Kong were the ones that made money.

The airline’s network reached its peak extent in 2013 (see map), since when Virgin has cut routes to Tokyo, Sydney, Mumbai, Accra and Cape Town. It has also withdrawn from Chicago and Vancouver, more closely aligning with Delta’s hubs with routes to Atlanta, Seattle and Detroit.

While the joint venture with Delta essentially saved Virgin Atlantic and enabled it to return to profit in 2014, earlier this year the airline said it was likely to fall to a loss yet again this year, thanks to a combination of Sterling weakness and tough market conditions. Virgin Atlantic’s previously stated ambition to beat its previous best-ever profit (£99m in 1999) by 2018 has quietly been forgotten, and the prospects for a global full-service airline that is (and always was) sub-scale are not exactly robust.

Fleet changes

The airline continues with a complete fleet replacement programme (which runs from 2011 to 2021). In 2016 Virgin Atlantic received four 787-9s (the first arrived in October 2014) and placed an order for 12 A350-1000s (with a list price of $4.4bn), which will start arriving from 2019 and will be all delivered by the end of 2021.

The fleet now stands at 40 aircraft (with an average age of more than eight years), and comprising 10 A330-300s, eight A340-600s, eight 747-400s and 14 787-9s. The formal outstanding order book with the manufacturers includes three remaining 787-9s (due for delivery by the end of 2018) plus six A380s and the eight A350s (the other four are coming via lessors). It is gradually increasing the number of owned aircraft towards a target of 50% of the total fleet, which it says “will lead to lower ownership costs”, according to CFO Tom Mackay.

The A380s were ordered more than a decade ago and keep getting deferred — and although the airline insists that delivery remains a feasible option, it’s becoming increasingly unlikely they will ever be delivered.

The new 787-9s are being deployed on Virgin Atlantic’s longest routes, while the A350s will replace the elderly 747s (which have an average age of more than 18 years) and A340-600s (with an average age of 11.5 years). The airline is also due to receive four former Air Berlin-owned A330-200s in early 2018, which will provide temporary capacity for the expanding Manchester hub (reportedly on initial 12-month contracts).

Codesharing with Flybe was launched in 2016, and this has helped Virgin Atlantic turn Manchester into a hub operation during 2017 (joining the existing hubs at Heathrow and Gatwick), with new routes from there (in partnership with Delta) launched to San Francisco and Boston, as well as extra capacity to New York JFK. Other new services this year included Heathrow to Seattle (part of the Delta JV), launched in March, Gatwick-Varadero (launched in April) and Heathrow to Barbados (December).

Meanwhile in December it announced a new code-share agreement with Virgin Australia (with whom Delta has an immunised JV on the Pacific), with connections through both Hong Kong and Los Angeles.

Strategically, however, it could be argued that Virgin Atlantic has little room to manoeuvre as it faces fierce pressure on fares from LCCs and others. A recent tactic of encouraging inbound markets to the UK (thanks to the plunging Sterling) through more sales effort in Asian markets smacks of desperation, and will hardly move the dial. Certainly the airline has no choice other than to continue as a full-service carrier — it continues to focus on its premium products, while in September this year it became the first European airline to offer wi-fi (on a paid-for basis) across its entire fleet globally, via a contract with service providers Panasonic and Gogo.

Virgin Atlantic continues to shrink, and capacity has been eased back again in 2017 to offset what the airline calls “demand challenges”.

Fading into the memory already is the airline’s ill-fated attempt at a UK feeder carrier — Virgin Atlantic Little Red. This was launched in 2012 with four A320s wet leased from Aer Lingus and using former BMI slots at Heathrow that had to be given by following BA’s acquisition of its smaller rival — but was folded in 2015 after poor load factors.

Though trying its hardest, Virgin Atlantic has essentially failed in its goal of becoming a true rival to a strong home carrier — British Airways. It has the advantage that London Heathrow provides — the strongest natural long haul O&D demand, and the prime gateway to Europe. But Virgin’s long-haul network is significantly sub-scale compared with BA, has little feed, and while the Virgin brand undoubtedly is highly valuable, on its own this clearly isn’t enough to make an airline successful. The long-haul routes it cherry-picked as being ripe for taking business away from BA are now being cherry-picked themselves by long-haul LCCs, and Virgin Atlantic will only survive long-term by being part of a broader, stronger airline alliance — with much deeper pockets.

Branson’s dream

Branson has won his bet with BA’s Willie Walsh made in 2012 over whether the Virgin Atlantic brand would still be around five years from then (the precise anniversary has just passed, which will no doubt result in a comical interpretation of the bet, where the winner gets to kick the loser in the groin).

Yet in June 2017 Richard Branson’s Virgin Group agreed a deal to sell 31% out of its existing 51% stake in Virgin Atlantic to Air France-KLM for £220m (funded by Delta and China Eastern each taking a 10% stake in Air France-KLM). The aim is no doubt to merge the Delta/Virgin joint venture with the long-standing Delta/Air France-KLM atlantic JV. Meanwhile, Air France-KLM’s partnership with Jet Airways (currently code share, but possibly to be deepened into a full metal neutral JV) allows a link between the Indian subcontinent and the Skyteam atlantic JV through London — and has allowed Virgin to reopen marketing of the Mumbai route as a code share on Jet.

While Branson made noises about Virgin Atlantic being a tighter part of the burgeoning Skyteam partnership, Virgin Atlantic is but a peripheral part of this broader aviation powerhouse. In one sense (and maybe a bit harshly) the reduction of the Virgin Group’s stake can be seen as almost the final nail in Branson’s once-held ambition to build up a network of Virgin-branded airlines around the world — see Aviation Strategy, August 2009.

Virgin America was acquired by the Alaska Air Group in 2016, with the Virgin brand due to be phased out by 2019, while the Virgin Group now only has an 8% stake in Virgin Australia (formerly Virgin Blue). Elsewhere Lagos-based Virgin Nigeria was always sub-scale and lossmaking, and the Virgin Group escaped its investment back in 2010. Branson’s dreams of Virgin airlines everywhere from India to Brazil to Russia remained nothing more than that — dreams.

Given the offshore and/or private nature of the Virgin Group and many of its businesses, maybe the story will never be truly told of how funds flowed between the various Virgin airlines and the rest of the Virgin empire, particularly as historically Branson funded some of his businesses with cash generated from other of his businesses. Though still chairman of Virgin Atlantic (which he founded back in 1984), Branson’s global aviation dream has long faded, and it’s inevitable that one day (maybe soon?) the Virgin brand will disappear for ever from the aviation world. When it does, the innovation and excitement that Branson brought to the staid UK aviation scene at the time should at least be remembered.

| In Service | Order | Options | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 747 | 8 | 8 | ||

| 787 | 14 | 3 | 7 | 24 |

| A330 | 8 | 8 | ||

| A340 | 7 | 7 | ||

| A350 | 12 | 12 | ||

| A380 | 6 | 6 | ||

| Total | 37 | 21 | 7 | 65 |

Note: YE Dec. Prior to 2013 data show for year ended Feb of following year.