Virgin Blue - Australasia's LLC or Ansett reinvented?

December 2002

Virgin Blue, Richard Branson’s low cost carrier in Australia, is facing a key strategic choice as it prepares for an IPO in 2003.

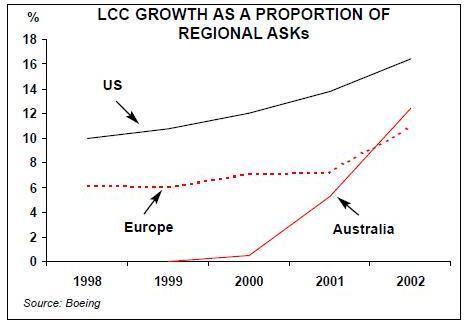

Does the airline keep to its initial low cost carrier (LCC) strategy, or will it be tempted to grow and fill the gap in Australian’s aviation industry left by the collapse of Ansett? When Virgin Blue was launched in August 2000 its mission was to provide LCC competition on Australia’s key domestic routes against both established carriers — Qantas and Ansett — as well as Impulse Airlines, an LCC that launched in June 2000.

Not surprisingly, the result was a vicious fare war that cost the industry A$500m (US$275m), according to the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation*. Most of the loss fell on Ansett, forcing it into administration in September 2001 before finally collapsing in March 2002. By then Impulse Airlines had already disappeared, in effect being taken over by Qantas in May 2001 after closing routes and wet–leasing its fleet to Qantas.

Through a mix of luck and judgement, Virgin Blue found itself in the enviable position of being the number two airline in a market worth some A$10bn (US$5.5bn) in domestic route revenue per year — but with just two airlines operating in total. Today Virgin Blue’s market share is estimated at 15–20% of the Australian domestic market, although (in common with most of Sir Richard Branson’s empire) getting up–to date revenue or profit figures for Virgin Blue is almost impossible, and is likely to remain this way until an IPO prospectus is released in 2003. However, Branson recently stated that the airline was aiming for a net profit of A$100m (US$55m) for the current financial year (to March 2003). That is a significant achievement for a start–up that originally estimated it would take five years to make a profit after launching in 2000 — and the prime reason behind going for an IPO sometime during the first half of 2003.

The IPO on the Australian Stock Exchange will offer investors up to 20% of Virgin Blue, it is believed, and Goldman Sachs are likely to be hired to arrange the issue. Analysts estimate the airline will be valued around the A$1,450m (US$800m) mark on its stock market debut. This will ensure a nice return on shares sold at the IPO by the Patrick Corporation, the Australian transport and logistics company that bought 50% of Virgin Blue from Branson’s Virgin Group for A$260 million ($143 million), plus a premium based on Virgin Blue’s performance over the next three years, in March 2002.

This premium is calculated as an extra A$30m paid by Patrick for every A$100m increase in the capitalisation of the discount air carrier over A$600m at the time of "any future significant change in shareholdings".

At a A$1,450m IPO valuation, that would give Branson an additional A$279m for the 50% stake he sold to Patrick — which perhaps explains why the Virgin Group is so keen to get the IPO away, and why there has been a flurry of strategic initiatives over the last few months.

Strategic pressures?

At the time, the Patrick buy–in was seen as good move for Virgin Blue as the new ownership ensured that the airline was reclassified as Australian airline, allowing it to apply for international routes. But as well as this beneficial influence it is also possible that — whether accidental or intentional — Patrick’s involvement may now be affecting what had previously been Virgin Blue’s clear focus on the LCC model.

In March, Chris Corrigan, the CEO of the Patrick Corporation, said that it would not be a passive investment, and that "the key issue that will drive the management team in the next 12 to 18 months will be capturing a significantly larger share of the Australian domes–tic market".

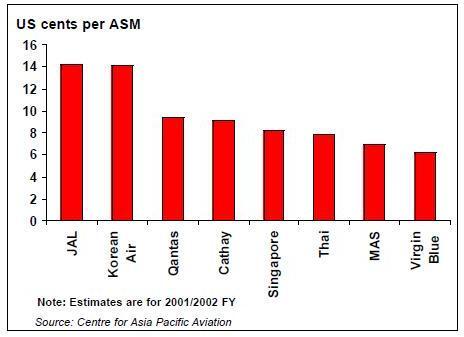

As largely point–to–point airline with a majority of sales made via its web site, Virgin Blue’s unit costs are some 35% less than Qantas, according to the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation (see graph, below).

But can that difference remain if, as some analysts fear, the airline has decided to move away from its profitable niche and instead challenge Qantas as hard as it can? Virgin Blue has a domestic market share target of 50% within five years — a target that, if is more than just marketing hype, will mean having to make substantial inroads into key Qantas markets. To compete hard against Qantas in all domestic sectors would surely decrease the cost gap that exists between the two.

And if Virgin Blue really wants to challenge Qantas, it knows that its larger rival earns three–quarters of its revenue from international routes, so that would mean significant international expansion for Virgin Blue.

And that is exactly what Virgin Blue is contemplating. Since the Patrick deal Virgin Blue has been planning international services, probably to start with services to New Zealand in 2003 and closely followed by routes to Pacific islands such as Fiji, New Caledonia, Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea. Virgin Blue may even be being bounced into starting international expansion sooner than planned, due to Qantas’s Australian Airlines, its new international, low cost subsidiary for leisure travellers. Virgin Blue’s plans for services to Hong Kong appear to be speeding up now that Qantas has requested permission to operate four more flights there, which if granted by Australia’s International Air Services Commission would means that Qantas accounted for 33 of the 36 frequencies allowed on the Hong Kong–Australian sector.

Virgin Blue reacted to the announcement in November that Qantas was going to buy 22.5% stake in Air New Zealand for NZ$550m (US$270m) by complaining to the New Zealand government about the monopolisation of New Zealand and trans–Tasman markets. It then suggested that it might be interested in buying Air New Zealand’s LCC subsidiary Freedom Air.

Indeed, there are signs that Virgin Blue is started to get obsessed with Qantas an echo of Virgin Atlantic’s relationship with BA.

Despite gaining a strong hold in the Australian market, Virgin Blue seems to be attacking Qantas with all the legal and regulatory means at its disposal (such as by pressing the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to release its report into alleged predatory practices on the Adelaide–Brisbane route) — perhaps echoing Virgin Atlantic’s obsession with British Airways in the 1990s. And the more that Virgin Blue gets concerned about everything that Qantas does, the more likely is to forget its original LCC mantra.

International expansion will be challenging. As most international routes would notwork with a low–cost, no–frills model, they are likely to be operated by a subsidiary of Virgin Blue (raising the improbable spectacle of an LCC having a "high–cost" subsidiary) or by a separate company altogether, possibly under the name Virgin Pacific (according to David Huttner, commercial head at Virgin Blue).

In the short term the setting up of even a separate international airline would seriously distract the Virgin Blue management team.

And anyway, could an international start–up really be kept at arms length from Virgin Blue in operational terms? "Virgin Pacific" flights out of major Australian airports would surely use the staff and facilities of Virgin Blue — or would a completely new infrastructure be set up at Australian airports to serve Virgin Pacific only?

Fleet decisions

And then there is the problem of aircraft. Virgin Blue has a fleet of 29 737s fleet, most of which are on operating leases (see table, below). One further leased aircraft will arrive in the first quarter of 2003, but the airline has been contemplating an order for up to 40 narrowbody aircraft for several months.

The order was supposed to have been placed in the summer, but is now expected to be made before the end of 2002. But a 40–strong aircraft order would only occur if Virgin Blue decided to switch manufacturers, replacing 737s with a combination of A319s, A320s and A321s. If it sticks with 737s a smaller order would be more likely, an order for ten 737–900Xs has recently been mooted.

But other than for the shortest routes, international expansion will necessitate a completely new type of aircraft — larger, and with a greater range. This would mean either another order from Virgin Blue, to follow on from a narrowbody order, or else the airline will announce a single order for both types at the same time. Airbus is hoping that this requirement will encourage Virgin Blue to order A320s for Virgin Blue and A330s for Virgin Pacific, types that offer substantial commonality. Against this has to be set the costs of switching to a new narrowbody type, although it is assumed Airbus will again price its aircraft extremely cheap in order to score another surprise victory against Boeing. It may be a close decision, but some analysts believe that Virgin executives are talking up Airbus’s chances in order to get the best deal possible from Boeing, who they intend to stick with anyway.

A complicating factor, however, is Virgin Blue’s apparent plans to significantly expand its cargo capability — a move that may have "suggested" by logistics owner Patrick, but one that yet again is largely incompatible with a LCC strategy, this time due to longer loading and unloading times for aircraft with significant amounts of freight. But if Virgin Blue is serious about winning much more revenue from flying cargo, that could impact upon the aircraft type choice, as A320s can be palletised — unlike 737s, which are relatively more cargo–unfriendly.

But even without the strategic distraction of international routes and cargo expansion, Virgin Blue’s unit costs may be rising anyway.

Virgin Blue has been moved into a number of airport terminal previously used by Ansett — newer terminals with better facilities and which are more convenient for passengers, but which are inevitably slightly more expensive. For example, after resolving a long–running legal dispute with Sydney Airports Corporation, the operator of Sydney airport, Virgin Blue will move to Terminal 2, the facility formerly used by Ansett there. The airport deal signed is for 17 years. Despite denials, Virgin Blue may also be contemplating joining a global aviation alliance — a move that yet again is likely to increase costs. Virgin Blue is code–sharing with United on Brisbane–Sydney, to be fol–lowed by code–sharing on 12 other domestic routes, all out of Sydney or Melbourne.

This was perhaps more important to United than Virgin Blue, given that United’s Star Alliance lost its local partner when Ansett collapsed earlier in 2002, leaving oneworld as the only global alliance to have a presence in Australia, via Qantas. Virgin Blue claims it is not interested in joining the Star Alliance, although it did hold informal talks with Star member Air New Zealand at the beginning of 2002 (although they came to nothing).

Singapore Airlines, a major shareholder in Virgin Atlantic, is also in the Star Alliance.

The future

Ambitious international expansion plans, the move into cargo and a blinkered goal of 50% domestic market share are simply incompatible with remaining a low cost airline.

Over all this looms the shadow of the IPO, which — Virgin Blue’s owners apparently believe — becomes much sexier if Virgin Blue says its will challenge Qantas both domestically and internationally, hence dangling the promise of fat shareholder returns for years to come. Branson famously tore up a cheque from Air New Zealand of A$250 million for Virgin Blue in 2001. That proved to be a good decision, but going for an IPO and changing strategy in order to get the IPO away may prove a gamble too far for the Virgin Group.

The alternative — sticking with a core LCC business model that has proven effective, thus cementing Virgin Blue as a substantial niche player in the Australian market for years to come — may be simply too mundane for Branson and the bankers that advise him.

| Fleet | Orders | |

|---|---|---|

| 737-300 | 1 | |

| 737-400 | 1 | |

| 737-700 | 17 | 2 |

| 737-800 | 10 | |

| TOTAL | 29 | 2 |