Greek Seaplanes: Maldivian model,

Mediterranean potential

Seaplane operation is one of the most esoteric segments of the airline industry. Seaplanes have a romantic image but they can also be serious commercial propositions, notably in the Indian Ocean and on the North American west coast. Is there also potential in the Mediterranean?

A useful database on seaplanes, manufacturers and operators has been compiled by researchers at Munich Technical University for the EU, entitled FUSETRA (Future Seaplane Traffic). Their survey identified 136 seaplanes — propeller driven aircraft with floats as opposed to flying boats — in commercial service in 2018. The most popular type was the twin-engine 19-seat DHC-6 Twin Otter, accounting for 38% of the total, followed by the DHC-3 Otter and the DHC-2 Beaver, single-engine with 11 and 6 seats respectively, accounting for 20% and 26% of the fleet. The other significant manufacturer was Cessna whose planes, ranging from the 3-seat capacity Cessna 172 to the 9-seat Cessna 208 Caravan, made up 23% of the fleet.

The main seaplane airlines are shown in the table. Harbour Air, and its two smaller competitors Kenmore and Tofino Air, all operate in the archipelago off the border of the USA and Canada, with their networks centred on the Vancouver seaport.

| Cessna 185 | Cessna 208 | DHC-2 | DHC-3 | DHC-6 | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skywagon | Caravan | Beaver | Otter | Twin Otter | ||

| (3 pax) | (9 pax) | (5-6 pax) | (10-11 pax) | (19 pax) | ||

| Trans Maldivian Airways | 52 | 52 | ||||

| Harbour Air (Western Canada) | 1 | 14 | 18 | 6 | 39 | |

| Kenmore Air (NW USA) | 2 | 10 | 6 | 18 | ||

| Tofino Air (Western Canada) | 3 | 4 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Air Whitsunday (Australia) | 3 | 3 | 6 |

Harbour Air Seaplanes, a private company 75% owned by its Canadian founders and 25% by the Chinese manufacturing company Zongshen, carries about 400,000 passengers per year on a combination of scheduled and charter flights, using a fleet of DHC-2s and DHC-3s. Mail and freight is as important for Harbour Air as passengers — remote communities rely on this service, and volumes are been boosted by Amazon-type shopping.

Trans Maldivian Airways

Trans Maldivian (TMA) is the global leader in the seaplane universe.

TMA evolved from a helicopter operation, Hummingbird Island Aviation, established by Danish entrepreneurs, transitioning to seaplanes in 1999 and merging with another seaplane operator Maldivian Air Transport in 2013 when they were bought by a private equity fund managed by Blackstone. The founders and majority shareholders — Lars Erik Nielsen, Lars Petré and Hussain Afeef — retained director positions and a minority holding in the new TMA. It was a private transaction but the investment was reported to be in the order of US$120-150m.

For Blackstone this was not an excuse to send stressed financiers to recover in a tropical paradise but a hard-nosed deal which produced one of its best returns in Asia. In December 2017 Bain Capital led a consortium that acquired TMA for an estimated US$600m, of which half was raised from a loan secured on TMA’s assets, giving Blackstone an estimated RoI of 47% pa over four years. Apart from Bain which took an 80% stake the other significant partner in the purchasing was a Chinese tour operator, Shenzen Tempus; the Chinese now constitute the largest national group, 25% of the total, in Maldivian tourism.

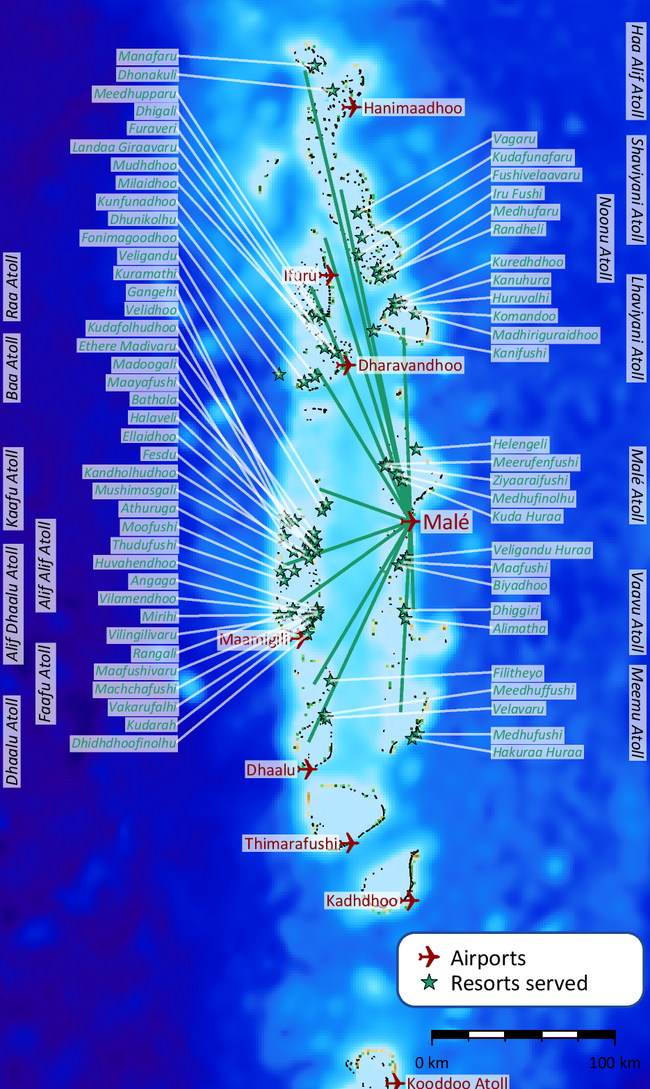

The Maldives is a perfect market for seaplanes — an archipelago of 1,200 island and islets in the middle of the Indian Ocean close to the equator where sea conditions are generally placid inside the protected lagoons. There is very little land available for buildings, let alone runways, and global warming is raising sea levels.

TMA operates a fleet of 52 DHC-6s configured for a maximum of 15 passengers to allow for generous vacation baggage loads. The core business is the transfer of tourists from the seaplane terminal at Malé airport to 70 resorts in the archipelago. Each island has just one resort, and the connections are normally sold en bloc to the resorts as part of the tour packages. TMA also offers island hopping, short trips for sightseeing and fishing, VIP charters, walk-up tickets for independent travel plus medivac services.

TMA has its own dedicated terminal at Malé Airport, with four “runways”. The airport itself has two runways and is served, among others, by European network and charter carriers, the three Middle East super-connectors and three major Chinese airlines.

As a private company TMA does not publish financial data but it can be assumed that it is profitable, maybe very profitable. TMA is the sole airline operating to most of the islands within the Maldives, and the majority of its customers are wealthy — spending $500 to $5,000 per night on their Maldivian vacation.

According to TMA, it carried 960,000 passengers last year and operated 120,000 flights. It runs an efficient operation with 900 employees in total. It has fewer than two flying crews per aircraft; the DHC-6 is flown by two pilots, one of whom also acts as a cabin attendant, refuelling operator, baggage handler and security screener when needed. Landing charges are negligible as the planes park at jetties or pontoons — a DHC-6 requires about 400 metres of water for a take-off or landing — while the 23 lounges that TMA runs are self-funding through sales of drink and food. Maintenance is a major cost because of the saltwater environment — on a per hour basis comparable with that for a narrowbody jet.

Tourist arrivals to the Maldives have grown steadily and hit 1.5m in 2018. This is getting close to the maximum given the current number of hotels. The Maldives are a year-round destination but the peak season is December to March while the low season, because of the monsoon, runs from May to October.

The islands have been affected by social unrest and volatile political decision-making in recent years, an example of which was the privatisation of Malé Airport. In 2010 the Indian construction conglomerate GMR won a 25-year concession to expand and run the airport. In 2012 a new administration voided the contract, after complaints about delays, and renationalised the airport, having given GMR seven days notice. The airport has been renamed Velana, the family name of the Maldivian president.

Greek potential

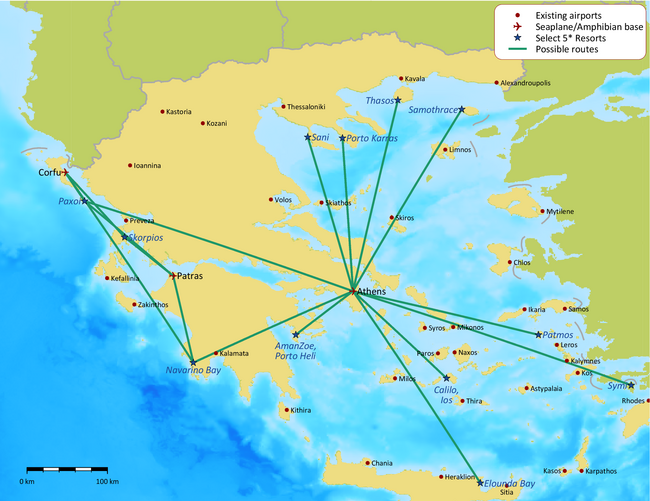

According to the Lonely Planet website, “Seaplanes are the buzzword for the 2019 tourist season in Greece”. Not yet is the reality, though there are some plans on paper: two companies, Hellenic Seaplanes and Water Airports have been involved in the arduous process of licensing water airports — the latter includes major Greek construction group Aktor in its shareholding. Aktor has just been awarded the long term concession of Alimos Marina (the largest in the Athens area) and envisions adding a seaplane terminal.

Greece, like the Maldives, has an archipelagic geography, but there are important differences. The two maps are to the same scale. The Maldives are clearly much more compact, while Greece has the eleventh longest coastline in the world and is the largest country in Europe (as measured in land and sea mass, from Corfu in the west to Rhodes in the east, from Macedonia in the north to Crete in the south).

There is a total of more than 160 inhabited islands, of which only 26 are served by an airport. From those relying exclusively on ferry service at least 30 are home to between 1,000 and 15,000 permanent residents — a population number that for the majority grows exponentially in the summer as Greece hosted 33 million visitors in 2018. About half of the 30 most populous non-airport islands project between 100,000 and 500,000 tourist ferry arrivals each in 2019.

Such traffic levels indicate viability for a limited seaplane scheduled network; however, such a network may well prove sustainable only in the peak season (June to September). For year-round service some government subsidy would be needed. Many of these remote islands qualify for Public Service Obligation (PSO) status.

There is currently no commercial seaplane service in Greece. Between 2004 and 2008 Air Sea Lines operated two DHC-6s mostly in the Ionian Sea, carrying 170,000 passengers on over 14,000 flights during that period, but went out of business having failed to establish operations in the Aegean Sea.

But could a Greek seaplane operation replicate at least some of TMA’s success?

The opportunity exists for a DHC-6 scheduled and/or charter operation to some high-quality resorts. Of a total of 500 five-star hotels, a significant number are geared towards high end vacationers who value ease of access and have the volume to support 2-3 weekly rotations to/from Athens — much like the TMA model. Examples include resorts (and resort clusters) like Costa Navarino in Peloponnesus, Porto Karras in Khalkidhiki, Calilo on Ios island, plus resorts in Elounda Bay in Crete, and in the Porto Heli area.

There is also a sub-market from the cruise business. In the summer an estimated 5,000,000 passengers typically visit four or five different islands in a week with a shore time of 6-12 hours on each island. Scenic tours by seaplane to view sites like Mount Athos, Meteora and Caldera in Santorini would appeal to some of the cruise passenger. (Cruise lines offer seaplane sightseeing when calling on Vancouver Harbour.)

Then there are vacationers, both Greek and foreign, who would just appreciate the speed of transit from Athens to their favourite island without mixing on overcrowded ferries with the hoi polloi (ie the crowds). This is not a market for the super-rich, who own or charter helicopters and yachts, but for the reasonably well-off, probably slightly elderly, customer.

Obstacles

Unfortunately, a web of bureaucracy between the several authorities involved (HCAA, Hellenic Coast Guard, Police, Customs, etc) is obstructing seaplane development. The licence for a water airport can only be issued to a public sector entity (typically the local Port or the Municipality) whereas a Water Airport Operator’s Licence can be granted to a private company. This differentiation is proving a deterrent for investing in the necessary infrastructure.

Key to developing an Aegean network would be an Athens Metropolitan water airport. There are a number of suitable locations but Greek regulatory processes are always an interesting challenge.

Current regulations dictate that all flights either depart or arrive at a licensed water airport to allow for a thorough security check on the one end of the flight at least. But at present there are only three licensed water airports — in Corfu, Patras and Paxoi, all in the Ionian Sea. This makes achieving any scale in network and charter routes a major challenge.

Whereas the Ionian sea in the west is relatively placid, the same cannot always be said about the much larger Aegean (where the prime seaplane destinations are). The strong summer northerly wind, known as the Meltemi, routinely reaches 5-6bF in force, which might eliminate many destinations with strong commercial potential simply because there is no suitable place to land under the prevailing sea conditions.

Finally, there is the issue of operating in a highly seasonal market. But, as mentioned above, the Greek and Maldivian markets are to some extent counter-seasonal; could there be the possibility of cross-leasing seaplanes?

This article appeared in Aviation Strategy Issue #246 May 2019.