Stockholm the key to Finnair's future

October 1998

As Finnair celebrates its 75th anniversary and prepares for privatisation in 1999, the airline is entering a crucial period. The airline’s strategy is clear — to mount an aggressive attack into Stockholm Arlanda, its arch–rival’s backyard. But will Finnair’s gamble work?

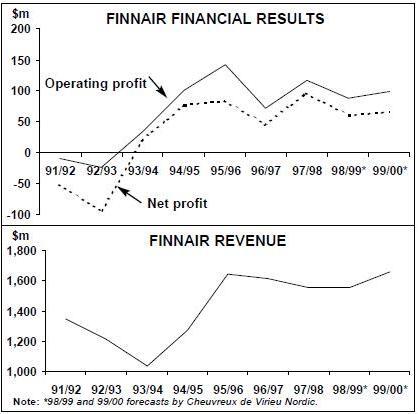

At first glance Finnair appears to be doing remarkably well. Finnair serves 21 domestic and around 50 international scheduled destinations, including North America (New York, Miami, San Francisco, Toronto) and the Asia/Pacific region (Singapore, Bangkok, Tokyo, Beijing, Osaka). In addition the airline has substantial leisure market business — of the total 7.1m passengers flown by Finnair in 1997/98 (a 12.5% increase on 1996/97) charter flights accounted for 11%. And Finnair recorded net profits of FM510m ($95m) in 1997/98, 58% up on 1996/97, with a net profit margin of 6.3% (compared with 4.4% in 1996/97).

However, 1997/98 may prove to be Finnair’s peak in the 1990s. Finnair’s management forecasts that “because of tough competition financial results for the current year may fall short of those for 1997/98”. Yields have already fallen 10% in the last four years, and operating profit was flat in the first quarter of 1998/99 (April–June 1998) despite an increase in passengers carried of 9.7%.

The main reason for sluggish results in 1998 is SAS and the Star alliance. The Nordic market (Scandinavia, the Baltic states and Finland) covers 30m people but within that Finland is relatively isolated geographically. Finland is a small niche market, and Finnair cannot rely on that demand alone.

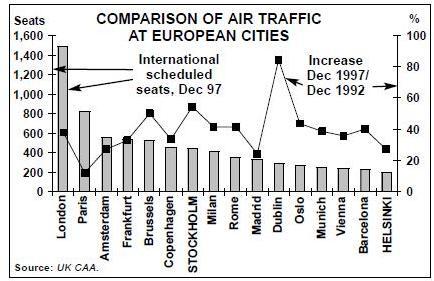

The key hub in the region is not Helsinki- Vantaa but Stockholm–Arlanda, which is the second–fastest growing airport for international departures in Europe (see graph, page 17). The airport has therefore become a key battleground between Finnair, which wants to set up a major operation there, and SAS — which not surprisingly considers Arlanda as “home territory”.

Finnair’s expansion into Stockholm has been substantial, although there is still a long way to go. Fifth–freedom operations at Stockholm accounted for 15% of Finnair’s total international flights by the end of 1994 and 24% by the end of 1997. Traffic on Finnair’s Sweden–third country services now surpasses passengers carried on its Helsinki–Stockholm route.

Today Finnair serves 20 destinations from Stockholm with approximately 50 flights per day, and the airline wants to operate further services in order to compete directly with SAS on even more routes to third countries.

Undoubtedly Stockholm is a more natural Nordic market link to eastern and southern Europe than is Helsinki, although “Finnish market feed from Helsinki is essential for Stockholm to be a real Nordic hub”, says Antti Potila, Finnair’s president and CEO. However, at present Finnair does not base any of its aircraft at Stockholm, although it is “looking at this very carefully”, according to Potila. At the same time Finnair has also expanded Stockholm–Helsinki services.

Inevitably, SAS has not taken too kindly to Finnair’s strategic move. Lufthansa’s code now appears on SAS flights from Copenhagen, Stockholm and Oslo to Helsinki while SAS’s code appear on Lufthansa flights from Frankfurt to Helsinki.

But Finnair code–shares with Braathens on Oslo/Stockholm, while Maersk and Finnair have code–shared on Copenhagen/ Stockholm since April 1997. On the latter route (which carries 1m passengers per year) Finnair/Maersk’s business fares are more than 25% below SAS’s prices, and the code–sharing deal is set to run for the next six years following approval from the European Commission.

The SAS empire strikes back

However, while Finnair is making some headway into traditional SAS strongholds, SAS is striking back via the domestic Finnish market, which accounts for 40% of the total scheduled passengers carried by Finnair, and 15% of revenue. In 1992 Finnair faced competition on just three domestic routes, but a combination of deregulation and SAS’s acquisition of Finnish airline Air Botnia in January 1998 has overturned the $1 of the last domestic market in Europe with virtually zero competition.

Air Botnia now operates on seven of the eight largest domestic routes in Finland (the exception being Helsinki/Oulu, the busiest route), and SAS intends to add more turboprops to Air Botnia’s fleet. And SAS is also considering new routes to Finnish provincial towns, to add to the estimated 25% market share of international routes to/from Finland that SAS and Lufthansa already have.

SAS’s proxy airline in Finland is a severe threat to Finnair. Some analysts feel that Finland’s isolation is a key strength for Finnair — Cheuvreux de Virieu Nordic comments: “Finland ... is not a market where the global companies feel the need for market share”.

However, the very smallness of the Finnish market (even though the domestic economy is strong) is also a key weakness of Finnair and means that that the airline has to expand into other Nordic markets — and that means encroaching on SAS. Inevitably that has resulted in SAS’s foray into Finland itself.

Strategically however, that is a risk that Finnair has to take. And Finnair knows that it is taking on not just SAS but the entire Star alliance — Air Botnia, for example, also provides feed to Lufthansa, with whom Finnair ended a six–year old co–operation agreement in October 1997.

The logical consequence of taking on the Star alliance is that Finnair had to align itself with one of the other global alliances. According to Finnair, 14 code–share agreements and nine seat purchasing agreements brought in FM209m ($40m) in 1997/98, representing 3.5% of air transport revenue. However, these agreements are minor compared with the potential of Finnair’s chosen global alliance — the British Airways/ American grouping.

The “Nordic Alliance” with BA, agreed in February this year, includes code–sharing between London, Manchester, Helsinki and Stockholm, as well as joint marketing and FFPs. Finnair will also join the full oneworld alliance. Finnair intends to leave its North America partner, Delta, as soon as possible so that it can ally with American in March 1999, ready for the 1999 summer timetable. In March this year Finnair signed a code–sharing agreement with LOT, and Finnair also has a code–share agreement with Iberia, in which BA is negotiating to buy a minority share.

What Finnair offers British Airways is northern European feed as well as a potential hub (Stockholm) for long–haul flights to the Asia/Pacific region on the transpolar route — although Potila says that “at present that is not feasible since our widebodies have to be serviced at Helsinki”. Just as importantly, an alignment with the British Airways grouping gives a psychological level of protection for Finnair.

The British Airways deal will also make up for revenue lost to/from Russia. Cheuvreux de Virieu Nordic estimates that the Russian crisis will knock $16m off Finnair’s 1998/99 profits. As for the Asian crisis, Finnair enjoys some protection since most of its long–haul passengers originate in Finland and not in the Asia/Pacific region itself. However, the airline does carry a significant amount of cargo to Asia, which will be hit.

But Finnair has powerful allies elsewhere in its battle with SAS. KLM too is challenging SAS — while SAS controls Air Botnia, Cimber Air and Wideroe, KLM partner Braathens has bought Malmo Aviation, the last nonaligned carrier in Sweden. And from last month (September) Finnair extended a code–sharing agreement with Sabena to five flights a day on Brussels–Stockholm and two a day on Brussels–Helsinki. This also brings Finnair closer to the Swissair/Sabena/ Austrian camp.

Maintaining a margin

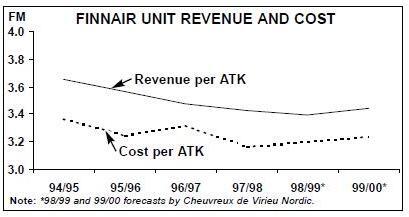

As can be seen in the graph below, unit revenues are declining and so cost–cutting is vital for Finnair.

At the start of 1997/98 Finnair launched a cost–cutting and productivity improvement programme called Programme 2. This aims to improve the bottom line by FM500m ($96m) over a three year period, and according to Finnair the programme is on target so far. However, even if Programme 2 is successful, Finnair’s profits will just stand still, as the FM500m improvement will merely offset an estimated FM500m erosion in profits over the next three years anyway due to increasing competition, according to Potila.

Programme 2 does not include personnel and Finnair is now also looking at this area, including the possible introduction of performance- related pay. However, union relations have not been great. Although a two–year collective agreement was signed with most staff in December 1997, pilots were not part of the deal.

After Finnair absorbed domestic subsidiaries Karair and Finnaviation in 1997 an attempt to standardise working conditions was strongly resisted by pilots, eventually leading to work–to–rule action and flight cancellations in March–May 1998. Although 530 jet pilots reached a deal with Finnair “along the lines of other labour agreements within the airline” in April 1998, the airline is still in dispute with 58 turboprop pilots at the former domestic subsidiaries. Potila states that “talks are continuing, and a settlement should be reached before the end of the year”. Finnair’s pilots are part of the Alliance Coalition, the grouping formed by pilot unions at 11 airlines in August 1998.

With 10 different aircraft types, Finnair’s fleet is not the most cost–effective. Although its 12 DC–9–51s have an average age of more than 20 years, last month (September) Finnair started refitting and hush–kitting them at a cost of $2.5m each. This will extend their life by 5–6 years. A few DC–9–51s may be sold, but the rest will remain in service.

The MD–80s (some of which were sold and leased back in 1997) will be replaced byFM2.2bn ($424m). Finnair should be able to finance this via cash flow and a relatively small increase in gearing. Further A320 family orders are likely. Finnair is also considering extra MD–11s for its long–haul fleet. And a fifth leased 757 for charter operations will arrive in April 1999. A question mark, however, remains over the future of the turboprop fleet. Domestic load factor was just 58.1% in 1997/98, and even if/when a deal with the turboprop pilots is completed, Finnair may have to contemplate franchising.

Other than personnel and aircraft, the other cost–cutting option for Finnair is outsourcing, such as maintenance, for example. This is an alternative that Finnair may have to explore given the likely cost pressures from factors outside its control. Fuel prices can only increase and the airline will continue to suffer from the Markka’s weakening against the Dollar (which is forecast to continue, according to the OECD).

Pre-millennium privatisation

The Finnish government first obtained a majority shareholding in Finnair in 1946, and it still owns 59.5% of the airline today. (Finnair is listed on the Helsinki stock exchange.) At present, the stock–market is applying a substantial discount to Finnair stock. The PE/ratio for Finnair is 9, compared with an average of 13 for all other quoted European airlines.

Full privatisation is tentatively scheduled for 1999 as part of the coalition Finnish government’s intention to sell “non–core assets”. The likely timeframe is after parliamentary elections in March 1999, with the government possibly retaining a small stake.

Senior executives in Finnair are in favour of privatisation, although some believe the airline could continue quite successfully with majority state ownership. “It’s good to have one large shareholder” says Potila, “whoever that is”.

How successful the sale of the government’s stake will be may depend on how far Finnair penetrates into Stockholm. Finnair’s strategy of expanding into the Nordic market by attacking SAS at Arlanda is fraught with danger, as it is provoking an SAS attack into the domestic market. Yet Finnair has little choice, because if it stayed in its home market it’s likely that SAS or Lufthansa would have challenged it there anyway in time. Potila says: “We decided that instead of desperately defending 100% market share in Finland, it would make more sense to win share elsewhere.”

But even if it does establish itself at Stockholm (and to do that it will have to base a substantial part of its fleet there), Finnair is still a niche carrier — and as such it had to have the insurance of “signing up” with a global alliance. British Airways was the obvious choice, but in many respects at present Finnair needs BA more than BA needs Finnair, at least until Finnair can deliver a beefed–up Stockholm operation.

Once Finnair is privatised, if it wants to it will be free to pursue much closer links — possibly including equity — with BA than are possible now (due to the current government stake). That may be Finnair’s salvation long term, and this will be one of the most important decisions that Keijo Suila, who takes over as president and CEO from Antti Potila in January 1999, will have to take.

On other other hand, Finnair — like all other small members of alliances — must be careful that it isn’t exploited by the likes of BA and AA. But if Finnair can upgrade its foothold at Arlanda into a substantial hub operation for the Nordic region, then the airline will have something really concrete with which to hook BA and the oneworld alliance long–term.

| Current | Orders | ||

| fleet | (options) | Delivery/retirement schedule/notes | |

| 757-200 | 4 | 0 | All leased and used for charter |

| flights. A fifth 757 will be leased in | |||

| April 1999. | |||

| DC-9-51 | 12 | 0 | Being hushkitted |

| MD-11 | 4 | 0 | |

| MD-80 | 25 | 0 | 12 on lease. |

| A300 | 2 | 0 | Leased out |

| A319 | 0 | 5 | 2 in 1999, 3 in 2000 |

| A320 | 0 | 3 (24) | 3 in 2000. Options are for A320 |

| family aircraft. | |||

| A321 | 0 | 4 | 2 in 1999, 2 in 2000 |

| Saab 340 | 6 | 0 | 3 on lease |

| ATR-72 | 6 | 0 (2) | 1 on lease |

| TOTAL | 57 | 12 (26) |