Iberia - a worthwhile gamble for investors?

April 1998

Following a return to profitability in 1996, Iberia is set for full privatisation by mid–1999. Should potential investors regard recent restructuring as the foundations of a truly competitive European airline, or should they be wary about investing in an airline with a troubled past and which faces major challenges over the next few years?

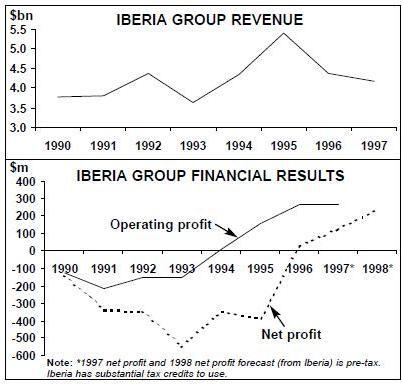

At first glance, Iberia’s financial performance is encouraging. Following a sea of red ink in the early 1990s, which almost led to bankruptcy, the group returned to profit in 1996 (see graph, right), and posted a provisional net profit, before taxes, of Ptas 18.4bn ($126m) in 1997. Iberia, the airline, accounted for Ptas 14.4bn ($98m) of this group total, almost double what the airline had forecast a year earlier. And group net profits are set to almost double in 1998, according to Iberia.

But investors must weigh these profits against Iberia’s troubled record over the last seven or eight years. A key concern is whether the strategic errors that led to the need for two huge injections of cash from the government will ever be repeated.

The first cash injection — Ptas 120bn ($1.2bn) of state aid in 1992 — was largely wasted on Iberia’s Latin America adventure. Iberia had wanted its partners — Aerolineas Argentinas, Ladeco and Viasa — to renew fleets and develop feed onto European routes, but even with Iberia’s help these airlines struggled and further cash had to be invested. In total, during 1992–94 Iberia pumped more than Ptas 290bn ($2.8bn) into its Latin America partners via loans and capital injection.

Inevitably, Iberia experienced severe balance sheet weakening and it was forced to apply for a further Ptas 130bn of state aid in 1995. Iberia made some ridiculous excuses: recession, the depreciation of the peseta and industry liberalisation, but the prime reason why Iberia had to be bailed out — the failure of its Latin America strategy — was due entirely to Iberia itself.

In January 1996 the European Commission finally agreed to Ptas 87bn ($687m) of aid, although this was not classified as state aid but rather as the actions of a “rational investor” — i.e. it was an investment made under market conditions.

From past to future

So does Iberia now possess a coherent, logical strategy that will lead to profits year after year, or will Iberia be as profligate with its cash as it was in the early 1990s? Although the group’s turnaround began in 1994, the real impetus for change came when the EC allowed the latest rescue package to go ahead. The EC was clear on how the money should be spent — Ptas 37bn for reducing the labour force and Ptas 50bn for repaying debt. Crucially, the EC only agreed to the Ptas 87bn injection and further "aid" of Ptas 20bn in the first quarter of 1997 if certain measures were taken and specific productivity and economic targets were met (although as yet this last tranche has not been allowed by the EC).

While the EC did not force Iberia to sell its Latin American stakes, divestment was the only way that Iberia could make its cash flow forecasts good enough to prove to the EC that there would be a “market rate of return” on the Ptas 87bn injection.

Iberia subsequently reduced its stake in Aerolineas to 10%, although Iberia is still responsible for the management of the airline. Elsewhere, Iberia disposed of its stake in Ladeco and, when unions rejected its proposed restructuring plan for Viasa, Iberia acted tough and liquidated the airline (although sale of the assets has yet to be completed).

Latin American divestment aside, Iberia and the Spanish government were left in no doubt by the EC that the airline had to make major strategic changes, and the initial tool that the airline used was called CAP — the Competitive Adaption Plan.

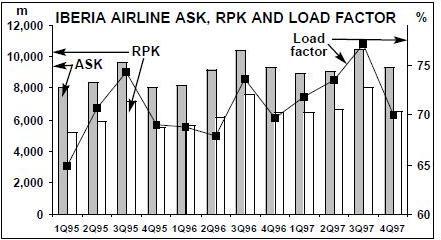

Cost–cutting was key. It began back in 1995 but gathered pace in 1996 when Xabier de Irala — who had a commercial background — became Iberia group chairman and CEO. By the end of 1997 the group workforce had been reduced by 4,500 via voluntary redundancy and early retirement. Wages were cut by by almost $50m in 1995–97, partly through the introduction of profit–related pay, cuts in rest days etc. In March 1996 a productivity deal was agreed with unions, incorporating changes to Iberia’s flight schedule. By Aviation Strategy’s calculations productivity has leapt ahead. ASKs per employees at Iberia airline grew 9.3% in 1995, 10.7% in 1996 and 8.8% in 1997.

Iberia is also cutting costs by finally beginning to revamp its over–complicated fleet (see table, left). Fleet renewal will help solve another problem facing Iberia — a shortage of capacity. As load factors continue to rise (see chart, page 16) lack of capacity is costing market share.

In the short–term, the airline is leasing aircraft, including 737s, 757s and 767s from Air Europa (see page 16), but capacity shortages will be eased more substantially once an MoU with Airbus for 50 A320–family aircraft (worth $2.6bn) plus an option for 26 more ($1.3bn), announced earlier in 1998, is firmed up in May. The first aircraft will be delivered this year, although many of them will replace 727s and DC–9s.

Iberia is likely to fund the Airbus deal via a mixture of operating and finance leases. Iberia is aiming for an equal share between ownership, finance leases and operating leases, but at present the majority of its fleet is owned outright. Financing options are being discussed with several banks, including the Luxembourg–based European Investment Bank, which is lending Iberia $185m to buy two A340–300s.

Iberia has also ordered 16 757s, to be delivered by 2000, and it is examining options for renewing its long–haul fleet.

Other measures taken over the last two years have included a new business class product in Europe, more competitive fares (although Iberia’s yield management is still poor compared with its rivals), and the introduction of an Iberia Plus loyalty card. In addition, Iberia will invest $40m in upgrading on board business and first–classes on long–haul by the end of this year.

Iberia’s network (96 destinations in 46 countries) will be expanded by new long–haul routes in the spring to Johannesburg and Chicago. But Europe remains at the heart of Iberia’s operations, and the 64 destinations served account for 73% of passenger revenue. Iberia is also increasing frequencies to certain European destinations, and new routes (e.g. Seville–Paris) are being planned.

The CAP was completed in 1996 and replaced by a Master Plan, which runs from 1997- 1999. According to Xavier de Irala, the Master Plan has eight strategic targets: "to boost marketing; improve connections at Madrid; reduce costs; integrate subsidiaries into the group network; sign airline alliances in Latin America; retain minority shareholdings in Latin America airlines; defend Iberia’s market share in handling; and equip the group with a differentiated management model."

In essence, the Master Plan boils down to yield improvement; cost–cutting/productivity gains and independence for company managements within the group umbrella (with the group planners concentrating on network and schedule management). Overall, Iberia appears to be progressing in the right direction, but does that make the airline a suitable case for privatisation?

Turning the corner?

Despite all the measures Iberia has undertaken, it could be argued that Iberia will be forever playing catch–up in the restructuring game. Iberia has begun cost–cutting measures later than just about all its major European rivals (Alitalia excepted), and the airline is now facing a range of new challenges which it will be hard–pressed to meet as well as keeping up its restructuring effort.

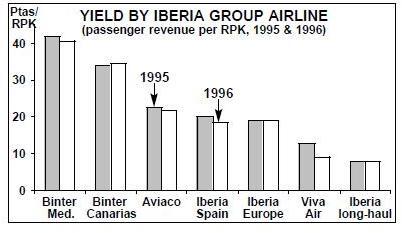

Perhaps the key challenge will be the impact of increasing competition in Spain (which is by far Iberia’s most lucrative market in terms of operating margin). This is coming from the Euro–majors, domestic competitors (e.g. Spanair, Air Nostrum, Air Track, Air Europa) and external low–cost airlines such as Virgin Express, easyJet and Debonair. Yield on Iberia’s Spanish operations fell an alarming 7.3% in 1996 alone (see chart, right).

Despite accusations of collusion between Iberia, Air Europa and Spanair, it will be difficult for Iberia to stem yield erosion. A deterioration in passenger mix and better Spanish rail links will not help, so Iberia’s only real alternative domestically is to cut costs. But labour costs can only be cut so far, and Iberia has therefore taken the first tentative steps towards shifting routes from its cost base onto other, cheaper alternatives.

In January 1998 Iberia signed a franchise deal with Air Europa, its main domestic rival. Air Europa will transfer 11 of its 34 aircraft to Iberia this month (April), complete with crews. Iberia says the deal is necessary "to combat increasing foreign competition in the domestic market", which is another way of saying that Air Europa’s fleet will be cheaper to operate than Iberia’s own.

Unions at Iberia airline reacted traditionally — on March 26 they took the first of 39 one–day strikes in protest ostensibly about the proposed seniority of the 122 Air Europa pilots compared with Iberia pilots. Talks are continuing and Iberia is optimistic that a settlement will be reached, but the strike symbolises residual union resistance to change. Nevertheless, on balance it is fair to say that unions are adapting to the new commercial environment at Iberia, although somewhat slowly.

With unions apprehensive about the forthcoming privatisation, a Spanish version of Go is out of the question at present — so Iberia has signed a franchise deal with Air Nostrum. Since May 1997 the airline, which uses Fokker 50s, has co–ordinated its flights with Iberia’s network, utilised Iberia’s distribution system, and used Iberia livery. As the relationship develops, and as long as Iberia’s unions do not object, Air Nostrum is likely to fly more low–density routes for Iberia — routes that Iberia cannot operate profitably but which are vital as they feed into Madrid or Barcelona. Further franchising deals are likely.

Competition is also impacting on Iberia’s lucrative handling contracts. Although Iberia has a contract with AENA, the Spanish Airports Agency, from 1992–2000, competition is increasing now that AENA has awarded secondary handling licences at major airports.

Privatisation

The privatisation process starts in the summer, although full privatisation will probably not be completed until mid–1999. The process has three stages; in the first, "industrial partners" — i.e. airlines — will invest; in the second, Spanish institutional investors will take a stake; and in the third the remaining 60% of shares will be placed on the stock market. (Employees already own 8% of stock, and have a further 5% option.)

At least that is the plan. For political reasons, the Spanish government would prefer to see majority control of Iberia remain in the hands of Spanish investors, but the two most likely external investors — British Airways and American Airlines — may see things rather differently. They are pressing for large slices, and initially wanted 40% of Iberia each. SEPI (Sociedad Estatal de Participaciones Industriales), the state holding company that controls Iberia, instead suggested BA and American buy just 5% each. Talks are continuing, and the latest news is that SEPI has raised its offer to 10% each for BA and American. Whatever the percentage, a substantial BA/American stake in Iberia would be logical (at least it would be for BA and American). In April Iberia starts code–sharing with American into North America, and American owns 10% of Aerolineas. Given American’s penetration of Latin America, the addition of Iberia to the BA/American axis could create a powerful strategic triangle, linking Latin and North America, North America and Europe, and Europe and Latin America.

However, there remain major hurdles to BA and American achieving large stakes. Not only may the government be wary of a major Anglo- American stake in Iberia (although a BA investment would surely improve the attractiveness of Iberia to small investors), but it appears that Iberia’s management may prefer a different route. Xabier de Irala has been reported as saying he would prefer an alliance with Air France, even though talks held between Iberia, Alitalia and Air France broke down last year. But whoever Iberia eventually allies with, it realises that it cannot afford to be left out of the mega–alliance process.

The real value in Iberia

Before potential investors start putting a price on Iberia, they should step back and consider what they are really buying. For all the troubles the airline has gone through, investors are buying into the future, not the past. Management has improved, unions are (slightly) more realistic and restructuring is working. That is not to say that the early years of a privatised Iberia will not be trouble free — the impact of competition on Iberia’s core market, Spain, will be severe, and in the worst scenario, investors may even have to bailout the airline yet again.

But investors must look long–term, and their decision should be guided by an analysis of the fundamental assets that Iberia possesses.

The first of these fundamental assets is Spain’s geographical/cultural position. Even if its initial strategy was nothing short of disastrous, at least Iberia realised that Spain could sell itself as the European gateway to/from Latin America. Instead of direct stakes, Iberia is now refocussing on winning feed via code–sharing. Iberia plans to increase capacity to Latin America by 50% in 1998–1999, from 276 flights per week to 420 (although its four aircraft based in Miami will be withdrawn once a code–sharing deal with “another airline” is completed). But capacity is not everything (see table, above left), and Iberia’s performance on Latin American routes remains unimpressive. Longer–term, Iberia could also develop routes into Africa, and perhaps Madrid could become the BA/American link into Africa.

The second fundamental asset underpinning Iberia is its domestic slot dominance. There is an acute slot shortage at Madrid and, to a lesser extent, Barcelona. Rivals have complained about Iberia’s slot power but, as with BA, slot dominance takes a long time to diminish. What Iberia has yet to do, however, is use the Madrid and Barcelona slots it has to their fullest advantage, although it is now increasing connecting flights.

Measuring the value of Iberia’s slots and its geographical position at the south–western corner of Europe is not easy, but that is essentially what investors are buying. The potential for better exploiting Iberia’s fundamental assets is great — as BA and American may well be contemplating.

| Current fleet | Orders(options) | Delivery/retirement schedule/comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 727-200 | 28 | 0 | To be replaced by A320s |

| 737-300 | 9 | 0 | Operated by Viva Air |

| 747-200 | 7 | 0 | |

| 757-200 | 8 | 16 | Eight in 1999 and eight in 2000. |

| A300 | 6 | 0 | To be replaced one-for-one by A320s |

| A319 | 0 | 9* | Four in 2000, five in 2001. |

| A320 | 22 | 26 (10)* | Two in 1998, eight in 1998, eight in 2000, eight in 2001 and 10 in 2002 |

| A321 | 0 | 15 (16)* | Two in 1999, three in 2000, two in 2001, two in 2002 and 22 in 2003/2004 |

| A340 | 6 | 2 | Delivery in 1998 |

| DC-8F | 3 | 0 | |

| DC-9-30 | 25 | 0 | 19 operated by Aviaco. To be replaced by A320s. |

| DC-10 | 4 | 0 | |

| MD-87 | 24 | 0 | |

| MD-88 | 13 | 0 | Operated by Aviaco |

| ATR-72 | 10 | 0 | Six operated by Binter, four by Air Nostrum |

| CN-235 | 8 | 0 | Operated by Binter |

| Fokker 50 | 15 | 0 | Operated by Air Nostrum |

| TOTAL | 188 | 66 (26) |

| Capacity ASK bn | Load Factor | RPK growth 97/96 | |

| South Atlantic | |||

| Iberia | 5.34 | 75.4% | 5.2% |

| BA | 3.65 | 71.8% | 8.1% |

| Lufthansa | 3.62 | 80.1% | 23.3% |

| Alitalia | 3.45 | 77.5% | 7.8% |

| Air France | 3.00 | 79.7% | 9.6% |

| KLM | 2.12 | 81.8% | 14.7% |

| TAP | 1.76 | 79.0% | 8.2% |

| Swissair | 1.39 | 76.8% | 36.8% |

| Mid Atlantic | |||

| Air France | 12.60 | 79.0% | 4.0% |

| KLM | 9.47 | 78.1% | 22.1% |

| Iberia | 7.26 | 78.5% | 14.1% |

| BA | 6.05 | 75.4% | 5.3% |

| Lufthansa | 2.85 | 79.1% | 0% |

| Alitalia | 1.56 | 75.0% | 20.3% |

| TAP | 0.60 | 79.9% | 22.1% |