Ryanair – to fly or to park?

June 2011

At the publication last month of Ryanair’s annual results for the year to end March 2011, CEO Michael O'Leary surprised some by stating that the company may ground up to 80 aircraft (or a third of the fleet) in the coming winter season; and that this could include all 50 of the new 737–800s that he states are scheduled for delivery between September and March 2012.

One major problem for any transport system is to cope with seasonality inherent in travel patterns; whether it is the intra–day peaks and troughs of commuter mass rapid transit systems or the effects on airline demand of the timings of summer holidays, school breaks, or major sporting and cultural events. The aim for the operator is to provide capacity that will capture the optimum revenues through the peaks while having to manage efficient provision of capacity in the troughs. All airlines follow this course with a variation in levels of flying in the two main IATA traffic seasons; working their aircraft hard in their summer seasons and reducing flying in the winter when maintenance can be scheduled efficiently. But there is a pervading tendency to consider that once you take delivery of an expensive aircraft you have to do something to ensure that you at least cover the cost of owning it, and in normal circumstances that means flying it. For most operators parking a new aircraft only appears attractive in extreme circumstances. The Ryanair model has turned many industry preconceptions on their heads; is this another one?

Ryanair has run a load–factor active, yield passive operation – maximising volumes by minimising price, with the aim of pushing average yield up over time. This it has done very successfully, even though it has often been accused of flying “from nowhere to nowhere”. It has grown to become (according to IATA) the largest airline in the world by numbers of international passengers carried and has subsumed British Airways’ former advertising claim to be the world’s favourite airline (the world’s favourite in international RPK terms is now Emirates). It is the largest individual carrier on intra–European services with around 12% of the market.

A second major element in its model is what the industry knows but still hates to admit — that an airline is a commodity business, at least on short/medium–hauls. Ryanair has deliberately set out to ensure that its unit cost of operation is the lowest possible (with the full understanding that in a commodity business the lowest cost producer will always win), has the most reliable service, best on–time performance and fewest misplaced bags. To help achieve this exceedingly low unit cost Ryanair benefits strongly from the exceptionally good aircraft purchase prices from its deals with Boeing at the beginning of the 2000s.

It also has an emphasis on young aircraft, with a policy to churn the older equipment as they reach eight years old, before expensive maintenance kicks in. The current average fleet age is only 3.2 years. On top of this the company emphasises the need for variable costing: among other things the cockpit and cabin crew are largely paid on an hours flown basis.

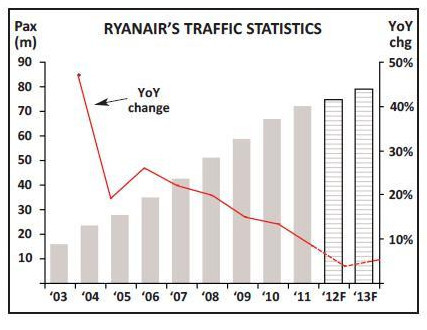

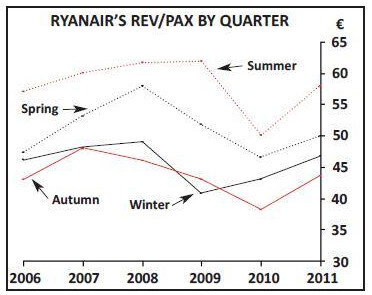

During last financial year (to March) the company acquired a net 40 new aircraft, opened eight new bases in Europe (and closed two) and initiated 328 new routes. The total numbers of passengers carried increased by 8% to 72.1m (and could possibly have been 1.5m higher except for the closure of European airspace due to the eruption of the Icelandic volcano (Ryanair at the time reported the numbers of passengers who had booked but not necessarily flown although non–flyers were not included in the annual totals). Average revenues per passenger improved by 12% year–on–year to €50.

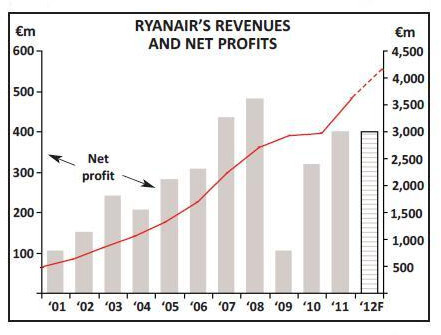

The full year results appeared reasonably impressive. Total revenue grew by 21% and despite a 37% increase in fuel costs (to €1.2bn or 40% of total operating costs), underlying net profits jumped by 26% to €401m. Unit costs excluding fuel apparently grew by 2% year on year (mostly because of staff costs and navigation charges). But, responding to a call from the Canary Islands to provide services, Ryanair nimbly did so and partly as a result increased average stage lengths by some 10%. Adjusting for this the company states that underlying adjusted unit costs actually fell by 7%.

The balance sheet meanwhile remains one of the healthiest in the industry. Capital expenditure in the year fell slightly to €900m and the company paid out a special dividend of €500m.

At the end of March gross cash and cash equivalents on the balance sheet stood at €2.9bn (or 80% of the previous year’s revenues) but on balance sheet debt had increased by €0.7bn to €3.7bn giving balance sheet net debt of €700m – or 25% of shareholders' funds.

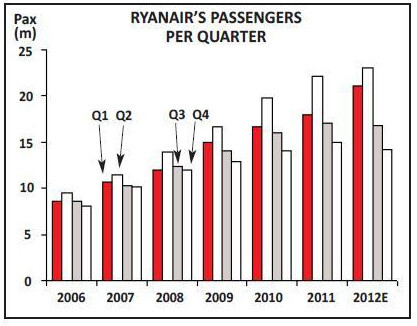

During the year the company continued a process of concentrating capacity growth in the first half of the year – during which, even after accounting for the effects of the ash cloud, traffic grew by 12%. In the second half of the year, the company grounded some 40 aircraft and curtailed overall capacity growth.

In the fourth quarter (the three months to end March) total traffic grew by only 6% though load factors improved by a percentage point to 75.5%. Partly as a result of this but also with a higher stage length, average revenue per passenger increased by 15% year–on–year to €46.90, and despite fuel costs rising by 23% on a per seat basis, operating losses in the quarter halved to €29m, or €1.50 on a per seat basis.

This, however, emphasises the seasonality dilemma: how much can you really afford to lose in the off–season?

Taking into account Ryanair’s fuel hedge positions (for 90% of its fuel requirement for the rest of the financial year to end March 2012 at around $820 a tonne of jet kerosene) and euro/dollar exchange rates, Ryanair’s fuel cost per seat in the last three months of the current financial year could be around €19, up by 32% year on year, and about 50% of aircraft–related unit operating costs (and assuming no change in load factors a fuel cost per passenger of over €25 or 55% of the per passenger revenue achieved). Estimating non–fuel costs per seat to rise by a modest 2% would give total unit costs per seat of €43, which compared with an unchanged achieved passenger revenue per seat of €36 could result in an operating loss of up to €7 per seat flown. Even assuming a 12% increase in yields there could be a loss per seat for the quarter nearly double the previous year, while to break even in the quarter could require a minimum 20% increase in fares.

In the results' presentation the management highlighted current plans suggesting that total Ryanair traffic (and capacity) in the current financial year will rise by no more than 4% overall – accelerating the slowdown in overall growth that would naturally occur when the last of the Boeing orders are delivered in FY2013. This once again will be heavily weighted into the first half of the year with increases expected in the June and September quarters of 18% (or 9% excluding the effects of the ash cloud) and 4% respectively; while it expects traffic in the December and March 2012 quarters to decline by 2% and 5%.

Its prognosis for profitability in the current year also shows increased seasonality: higher profits in the first half because of higher volumes and yield growth; greater losses in the second half mainly due to higher fuel costs; capacity cuts in the second half to limit losses and protect full year profitability. Overall it anticipates being able to achieve profits similar to 2011’s €400m on the assumption of another 12% increase in yields.

Ryanair in recent years has tended to schedule a large portion of its aircraft deliveries for the off season; using them to introduce new routes, create new bases as well as increasing density of operation at existing operational bases. This coming year is no different in that the company appears due to take 32 new 737- 800s between September and March. This time, however, the company appears to have decided to keep these aircraft on the ground from delivery until the start of the next financial year as well as grounding perhaps another 50 aircraft (up from 40 last winter).What might be the marginal operative benefit to Ryanair for not flying its new aircraft? The winter quarter for many airlines tends to be of questionable profitability at best and at current anticipated fuel prices loss making even at the operational level; so, increased flying will increase losses. For it to ground an aircraft the actual cost of doing so is likely to be little more than the effective ownership cost – it operates to enough airports where parking will be free.

Assuming, as a result of the Boeing deal in the 2000s, that the company is acquiring its new aircraft at around the $37m level (compared with an estimated current new achieved price of $42m) and following its statement that it has secured funding at 4% and hedged at €1.43 to the dollar we could estimate its ownership cost including depreciation at around €2m per aircraft per year, or €0.5m a quarter, or (at its average six departures a day) €5 per seat. Were these aircraft to be leased (and just under 50 of Ryanair’s 272 aircraft are on lease) at current market lease rates the cost could possibly work out 50% higher. So perhaps not to fly an aircraft for a quarter could just cost it €0.5m.

However, in doing so it is foregoing revenues (and losses). There is a naturally lower level of demand in the off season – and consequently lower unit revenues. In the past few years the premium of Ryanair’s average summer season passenger fares to those in Winter has fallen from 20% to around 10% (see chart on seasonal revenues per passenger, page 4) – but then in the last two years Ryanair has taken more aggressively to objecting to airport charges at Stansted and Dublin in particular and grounded aircraft at its more expensive bases – but has still put new incoming aircraft on new bases and routes in the off seasons. New routes take time to build to reasonable maturity and even with Ryanair’s model this will have had a dilutive impact on total unit revenues. We have guesstimated that a new route may suffer a 20% yield discount to the system average in its first months of operation and estimate that all other things being equal such routes would generate operating losses of €12 per passenger carried – and if the more expensive airports are included up to €17. This could imply that not flying a new aircraft on such routes might avoid operating losses of between at least €1m per aircraft for the winter quarter. Adding this to the assumption of ownership costs and speciously applying it all of the 80 aircraft the company may ground may suggest that by not flying its new aircraft Ryanair could improve profitability from what it otherwise would have been by €80m.

These plans of course are not set in stone – and the recent suggestion of the Irish Government to scrap the passenger tax and provide rebates on passenger fees should traffic exceed 2010 levels may go some way to allow Ryanair to reconsider its Dublin offering. Failing this, the reduction in winter planned capacity introduces a period of slow growth for the airline.

Having failed to reach an agreement with Boeing two years ago the last of the 737–800s is due to be delivered in 2013 – by which time (after disposals) the company will have 299 737s in its fleet carrying 79m passengers a year.

Having made the massive “land–grab” in the past decade this era of lower growth may allow a gradual improvement in the “quality” of its route network and perhaps a less aggressive competitive environment. Without the annual €1bn capital expenditure the company will be generating significant amounts of cash to return to shareholders – but this time O'Leary did say that some cash would be held back for new aircraft; but although the company admitted it had been in discussions with Russian and Chinese manufacturers these are unlikely to provide viable alternatives to the Boeing solution before 2017 (and Airbus apparently doesn’t even want to talk to Ryanair).