SAS Group: time for revolution, not evolution

May 2007

With improving financial results, the SAS Group has — in SAS Group–speak — gone from a "crisis/rescue phase to a conceptually driven restructuring". An imminent new strategic plan will offer "evolution, not revolution", but can the SAS Group survive long–term unless it is much more radical in what it does?

Today the Stockholm–based SAS Group is the fourth largest airline in Europe in terms of passengers carried (behind Air France/KLM, Lufthansa and Ryanair), but although Scandinavian Airlines — the flag carrier of Denmark, Sweden and Norway, (with hubs at Copenhagen, Stockholm and Oslo) — celebrated 60 years of flying in 2006, the airline and the Group have undergone a difficult time in the 2000s.

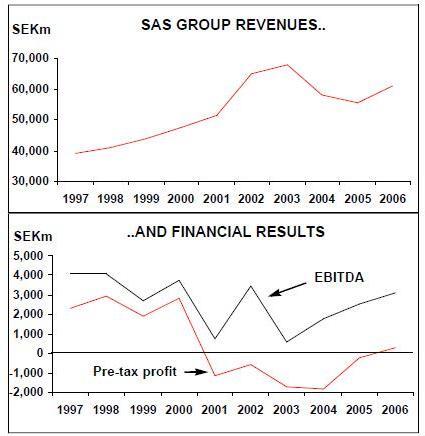

As the graph shows, profitability collapsed at the start of the 2000s, and it has been a long, hard road to recovery ever since, with waves of cost–cutting and restructuring just about the only focus of the Group through the decade. "Turnaround 2005", unveiled in 2002, took an estimated SEK 14bn (€1.5bn) of costs out of the Group in the period to 2005, but it was not enough, and yet another round of cost–cutting launched in 2006 is designed to cut a further SEK 2.5bn (€275m) in 2006 and 2007. Of this latest programme, around 85% of cost–cutting measures have been implemented, according to the Group, and this has translated into SEK 1bn of actual cost savings in 2006, with another SEK 1bn expected in 2007. Of the targeted SEK 2.5bn, SEK 600m is to come from better productivity, SEK 900m from cost savings at SAS Ground Services and Technical Services, and SEK 1bn from admin, sales and other costs.

At the same time as cost–cutting, the Group has been continuing its sale of non–core assets. Last year SAS Group raised a total of SEK 5.7bn (€626m) from the sale of its remaining 65% stake in its Rezidor Hotel Group, which operates 226 hotels around the globe. SAS sold a 35% share to Carlson Hotels in 2005, and the remaining stake was floated on the Stockholm exchange in November, with the IPO being nine times oversubscribed. It is also completing the sale of its stake in SAS Flight Academy — its pilot training arm — to investment fund STAR Capital Partners, which is merging the company with another investment it is making, a majority stake in General Electric Commercial Aviation Training. The disposal will benefit SAS Group by around SEK 750m, and SAS will obtain its future pilot trainings needs through an ongoing contract with Flight Academy.

On the back of cost–cutting and asset sales, in full 2006 (which for the first time did not include Rezidor, which — as one analyst puts it — means that the 2006 numbers are "extremely confusing") the Group’s financial results improved. SAS Group revenue increased 9.5% to SEK 60.8bn (€6.7bn) in 2006, and operating profit rose 88% to SEK 1,273m (€140m). Pre–tax profit rose from a SEK 246m loss in 2005 to a SEK 292m profit in 2006, and at the net level profit rose from SEK 255m in 2005 to an apparently healthy SEK 4.7bn in 2006, which came after deducting SEK 337m for restructuring costs (SEK 413m in 2005) and SEK 146m for impairment losses. But excluding discontinued operations, the net profit in 2006 was just SEK 164m (€18m) — though considerably better than the SEK 322m net loss (excluding discontinued operations) in 2005.

Inconsistent performances

As SAS admits, the Group is benefiting from being at the top of the business cycle at the moment, with strong GDP growth in most markets it operates in (and particularly strong traffic growth in Norway, Spain and the Baltic region). Yet SAS says it needs to improve its earnings by at least another SEK 3bn (€330m) a year. Put another way, a key Group target is a Cash Flow ROI of at least 20%-25% per year, but although this has risen from a low of just above 5% in early 2002, CFROI was just 15% in 2006 (13% in 2005), and there is a long way to go in hitting this objective. The Group’s constituent parts are still producing a wide range of financial performances, ranging from the impressive to the abysmal. As can be seen in the table, the worst performing part of the Group is SAS Aviation Services.

SAS Cargo is based at Kastrup in Denmark, and is one of the cargo airlines being investigated by the European Commission’s cartel probe (and for which the Group has made a SEK 50m provision for expected legal costs). But while Cargo made a SEK 99m EBT (€10.9m) before non–recurring items in 2006, and Ground Services chipped in a SEK 43m EBT (€4.7m), SAS Technical Services made a SEK 249m (€27.4m) loss in 2006 — which although better than the SEK 523m loss of 2005, is still dragging down the results of the entire Aviation Services division. Last year Technical Services closed a maintenance base at Stavanger, which will save an estimated SEK 200m a year, but this alone will not be enough to deliver a profit to the business unit.

Much more worrying for the Group is the inconsistency in the core of what SAS does — its airlines. In 2004 the Group split its mainline into four parts — SAS Braathens (which operates all Norwegian services, and which is to be renamed as Scandinavian Airlines Norway in June), Scandinavian Airlines Sweden, Scandinavian Airlines Denmark, and Scandinavian Airlines International — and again, the table, shows large differences in performance.

The powerhouse of the entire Group is SAS Sweden, which delivered an operating margin of 6.3% and SEK 525m (€57.7m) of EBIT in 2006, representing 41.9% of the Group’s entire EBIT in the year. The other Scandinavian operations, however, are less successful.

SAS Braathens has been going through troubled times recently, with the integration of Braathens, bought in 2002, into the SAS Group being more complicated than anticipated. Last year pilots and flight attendants carried out industrial action in pursuit of pay claims — with pilots carrying out so–called sick–outs (where an unusually high number of staff calls in sick) — and the unit has faced a number of legal challenges. Last year SAS Braathens was fined NKR 20m by the Norwegian competition authority after "abusing" its dominant position in the Norwegian market and forcing a local competitor off a route — although Braathens managed to overturn that decision in the local courts. More seriously, last year Norwegian "economic crime" investigators filed charges against SAS Braathens, alleging that it stole information from the computers of LCC rival Norwegian after the expiry of an earlier co–operation deal between the two airlines on the Stavanger–Newcastle route.

In 2006 Petter Jansen, the chief executive of SAS Braathens, resigned due to an apparent disagreement with SAS Group on the strategy for Braathens, and was replaced by Ola Strand, an SAS Group "loyalist", with 10 year’s experience there. What Strand will do with SAS Braathens (or will be allowed to do by the Group) is open to debate. SAS Braathens is called a "low–cost" operation, but it’s not in the same league as its fierce competitor, Norwegian, and indeed speculation persists that SAS Braathens will be turned into a fully–fledged LCC. But this ignores the reality that Braathens — as well as the other national SAS operations — can never truly become a low cost carrier due to legacy and structural costs.

Fundamentally, that means the unwillingness of the local workforce to allow erosion of what they see as "hard–won" pay and conditions. Already unions have posted effective warning shots to management over attempts put them onto national contracts (rather than pan–Group contracts) as part of the overall SAS strategy to "localise" its structure.

While Norwegian pilots went onto national contracts in 2004 as part of the Braathens/local SAS unit merger, Danish and Norwegian pilots staged a three–day wildcat strike in January 2006 at the prospect of national contracts, before a one–year pay deal (with a 2.4% pay rise) was agreed with all pilots in Sweden, Denmark and Norway in May last year — but only after a compromise of formal employment of Danish and Swedish pilots remaining in the SAS Group, even though pilots are supposedly part of the national SAS companies.

Industrial unrest is also breaking out among other sections of the workforce. In April 2007 the Group was hit by a three day wildcat strike by 1,600 members of the Danish Cabin Attendants Union (CAU) based in Copenhagen, who were protesting at the perceived lack of progress in new negotiations on pay and conditions for the 2006/07 labour contract. SAS only reached an agreement with CAU back in October 2006 on a one–year pay deal (back–dated to March that year, and expiring at the end of February 2007) after prolonged negotiations between the two sides that lasted 14 months. It was only after the union set a date for strike action in late 2006 that a deal was agreed, including a 3.5% pay rise. Meanwhile in Sweden 1,000 flight attendants represented by the HTF union also threatened industrial action in October last year, after talks on working conditions stalled (although management again headed off action with a new one–year deal), while Norwegian flight attendants also staged industrial action last year.

The reluctance of unions to accept erosion of their terms and conditions is a fundamental challenge to Mats Jansson, who became SAS president and CEO in January this year, taking over from Jorgen Lindegaard, who resigned in August 2006 after five years in the position. Lindegaard spent his time trying to restructure the group in the face of tough market conditions and resistance from unions, but a harder stance may be needed by Jansson, who previously headed up a Scandinavian consumer goods distributor. In early 2006 SAS Group said that it wanted to cut back its 2,000–strong pilot workforce as its operations were now "more efficient", but the issue has not been pushed by management — so far.

| Share of | |||

| Share of | operating | Operating | |

| revenue* | profit** | margin** | |

| Scandinavian Airlines | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| SAS Braathens | 17.5% | 26.3% | 2.6% |

| SAS Denmark | 15.2% | 14.8% | 1.7% |

| SAS Sweden | 11.5% | 41.9% | 6.3% |

| SAS International | 10.8% | 13.5% | 2.2% |

| Total Scandinavian Airlines | 55.0% | 96.6% | 3.1% |

| Other Airlines | |||

| Spanair | 15.3% | 16.8% | 1.9% |

| wideroe | 4.1% | 2.8% | 1.2% |

| Blue1 | 2.8% | -1.3% | -0.8% |

| airBaltic | 2.2% | 4.4% | 3.5% |

| Total Other Airlines | 24.4% | 22.7% | 1.6% |

| SAS Aviation Services | |||

| Ground Services | 8.2% | 0.5% | 0.1% |

| Technical Services | 6.8% | -29.0% | -7.4% |

| Cargo | 5.1% | 5.3% | 1.8% |

| Flight Academy | 0.6% | 3.9% | 11.1% |

| Total SAS Aviation Services | 20.6% | -19.3% | -1.6% |

Long-haul woes

The size of the workforce is naturally dependent on the strategy of the mainline airlines, and at last there appears to be some consistency in what those core airlines are doing. From start of 2006 the new mainline strategy has been based on a reduction of the dependency on a hub network, with a greater emphasis being given on building up profitable direct routes between Scandinavia and the rest of Europe. For the first time since 1995, long–haul routes reported a profit in 2006, but SAS only serves seven long–haul destinations (with a fleet of four A330s and seven A340s), and without scale the long–haul operation has been struggling. Though SAS plays an important part in the Star alliance — securing northern European feed and regional routes for the alliance — in terms of incoming feed into SAS’s long–haul routes, SAS doesn’t really benefit to any great extent from Star, as its geographical closeness to Lufthansa means that most Star business traffic to the south of Scandinavia tends to gravitate to long–haul routes out of Frankfurt.

Although capacity is slowly increasing out of Stockholm, Copenhagen remains the key longhaul hub for SAS, but the long–haul operation has been hampered by a lack of focus, as it has constantly been axing and launching services as it tries to find sustainable, profitable routes. According to Jansson, the idea on long–haul is to be "more demand–driven than ever before" through flexible capacity, for example by switching marginal capacity to North America in the summer and to Asia and the Middle East in the winter. The latest addition to the network is a four–times–a week service from Stockholm to Beijing, launched in March this year, on which SAS is code–sharing with Air China. SAS also serves Beijing from Copenhagen, but shut down a route to Shanghai from Copenhagen this April, in favour of making Beijing its preferred hub in China.

SAS’s only other Asia destinations are Bangkok and Tokyo. Although SAS already serves Bangkok from Copenhagen, a service from Stockholm is being relaunched this October after being dropped in 2003. This time around SAS says the route will be successful due to the growing importance of Bangkok (home of Thai Airways) as a Star alliance hub.

European adjustments

The other long–haul routes are to the US (Chicago, New York, Seattle and Washington), although SAS Group says that these routes have come under "severe competition" from US carriers, with Continental, Delta and US Airways all building up capacity into Scandinavia that had been cut following September 11. Nevertheless, SAS’s services to New York are being nudged up slowly, with a fourth weekly flight between Copenhagen–New York starting this May. Elsewhere, a three–times–a week Copenhagen to Dubai route using A340s will start in October, becoming the first direct link between Scandinavia and Dubai. On short- and medium–haul, in 2006 Scandinavian Airlines had a 33% share of the Nordic market (as measured by ASKs), rising to 45% if all SAS Group airlines are included. As SAS puts it, the network is being adjusted "to local traffic flows and profitable feeder traffic". And "dynamic traffic management was increasingly implemented in 2006, allowing Group units to adapt capacity to demand". Practically, for example, this means that the Denmark unit reduced its capacity substantially over the Christmas and New Year period (compared with previous years), as there is much lower demand then. As mentioned earlier, Scandinavian Airlines is also increasing non–stop routes out of Scandinavia, and five routes were launched out of Stockholm this spring (to Glasgow, Malaga, Munich, Palma de Mallorca and Reykjavik).

In terms of the product, it wasn’t until the results of a study at Star airlines were completed in 2004 that SAS made the discovery that up to 50% of its market was "price–driven", and that they didn’t value frills. A three–class service was therefore introduced on European services in 2004, including a premium–economy service with free meals, fast–track check–in and security clearance, and free rebooking and refunds. At the same time the business class product was overhauled to include no centre–seat occupancy in three seat rows, while the economy product was stripped back, with charges introduced for frills such as meals.

But while there is now a distinct no–frills economy product, it’s clear that SAS is focussing more of its mainline operation on business travellers. 60- 70% of SAS’s passengers are business travellers (whether they fly business or economy), which SAS Group says are "our main customers". In February this year Scandinavian Airlines began to make its offer to business travellers more "distinct", with the premium economy product promoted as saving time and money for business travellers.

In 2005 (and later than at virtually all its competitors) Scandinavian Airlines introduced flexible booking, enabling — for example — passengers to mix outbound business class with an inbound economy fare. The premium economy product has been renamed from Economy Flex to Economy Extra and is now available at lower fares, with extra frills such as internet check–in and as fast track security at more airports. And in Economy, free meals are now given to Gold members of SAS’s FFP, whom are being given a better range of FFP benefits. The business push is also extending into long–haul, and this April Scandinavian Airlines completed the installation of new business- class sleeper seats on its long–haul fleet, alongside an improved in–flight entertainment system

SAS Group says that its business travel is picking up, but pressure on both European business and leisure traffic is increasing from the LCCs. easyJet only operates a couple of routes to Scandinavia (to Copenhagen), but Ryanair operates 13 routes out of Stockholm Skavsta, although it too has been shifting capacity, and in May opens three new routes out of Stockholm — to Alghero, Marseille and Venice — that will replace three routes to Brussels, Kaunas and Gdansk. A bigger challenge to SAS comes from Air Berlin, which operates 12 routes from Stockholm, 13 from Gothenburg and 26 out of Copenhagen.

And then there is the growing threat from Scandinavian LCCs. Although Swedish LCC FlyMe filed for bankruptcy in March, FlyNordic (whose owner, Finnair, is selling the airline to Norwegian) operates 10 aircraft out of Stockholm Arlanda; Danish LCC Sterling operates a fleet of 24 737s to 35 destinations in Scandinavia and Europe (with a major presence at Copenhagen, Oslo, Stockholm and Gothenburg); while Oslobased Norwegian has a fleet of 22 aircraft, carried 5.1m passengers in 2006 and has just announced that it is to acquire 11 737–800s as it looks to expand its operations and replace older 737–300s.

Collectively, these LCCs are putting tremendous pressure on Scandinavian Airlines. Back in 2004 SAS said its strategy going forward would be based on a "network carrier at a low cost" concept, but although mainline airline units costs have been cut by more than a third over the last five years, "there continues to be a cost gap between SAS and rival airlines servicing the Scandinavian region" according to ABN Amro, and this is something that the new CEO must address as a matter of urgency.

Indeed on a Group basis, airline unit costs have remained pretty constant over the last couple of years despite the continuing efforts of SAS to cut costs. Snowflake — SAS’s LCC concept — was short–lived. After launching with four aircraft in 2003 it evolved into what was confusingly called a "fares brand", before being reabsorbed into the mainline carrier in 2005, with the rationale being that the lessons of Snowflake had been learnt and that the mainline unit costs had come down anyway thanks to ongoing cost–cutting.

A mixed bag of "others"

However, the latest SEK 2.5bn cost–saving programme reveals that costs still need to come down. But even reducing the cost gap with other network carriers is simply just not good enough for the SAS Group, as it is now primarily competing with LCCs. Worryingly, the Group appears to be increasingly relying on its "other" airlines to carry the fight to the LCCs, while the mainline operations refocus on the business market. While the mainline operations have a collective operating margin of 3.1% in 2006, the "other" airlines (the groups calls them "individually branded airlines") posted a measly 1.6% margin.

The poorest performer was Blue1. The Vantaabased airline was launched as Air Botnia back in 1988, but was bought by SAS in 1998 and rebranded as Blue1 in 2004.

It operates 12 aircraft on feeder routes from Finland to Copenhagen and Stockholm, but last year — in order to reduce its dependence on the stagnant Finnish domestic market — underwent a huge expansion on non–stop routes between Finland and continental European destinations. Eleven routes were launched in 2006, including to London Stansted, Paris, Rome and Zurich, and six new European routes are being added through 2007 (a Helsinki–Milan route began in April, for example), but further expansion on direct routes will be limited after this, due to a lack of aircraft. For the longer routes into Europe the airline added three MD–90s (leased from Scandinavian Airlines) to its fleet, which also includes nine RJs, with the last of its Saab 2000s having been phased out in 2006.

It’s not clear yet whether this is a sensible strategy and whether enough demand exists for lots of direct routes into continental Europe. Even if it is, in the short–term that expansion is very costly for Blue1, which reported an operating loss of SEK 16m in 2006.

The SAS Group also owns regional Norwegian airline Wideroe, but its profits fell in 2006 due to increasing competition, and in response the airline is midway through a programme to cut SEK 200m in costs. It is Spanair (of which SAS Group owns 94.9%) — the largest of the "other" Group airlines — that makes the least strategic sense for SAS. Justification for it comes from the view that it is the "Star alliance’s main point of access to North Africa," according to Gonzalo Pascual Arias, president of Spanair, but the airline is coming under fierce pressure from LCCs, not only from Ryanair, easyJet and Air Berlin, but also from Vueling and Clickair — Iberia’s new LCC (see Aviation Strategy, December 2006). Spanair too is implementing a cost reduction programmes designed to save SEK 200m, but the airline’s routes look detached when compared with the other parts of the SAS network.

Completing the rag–bag of "other" airlines is Riga–based airBaltic (47.2% owned by SAS Group), which was the pest performing non–mainline carrier in 2006 in terms of margin, but whose revenue base is small (SEK 1.5bn, or €170m). SAS Group also owns 49% of Estonian Air (acquired from Maersk Air in 2003), 25% of Swedish regional carrier Skyways, 37.5% of Air Greenland and 49% of Aerolineas de Baleares.

A frozen fleet

It’s not a convincing airline portfolio, and collectively they add little strategic strength to SAS Group. As ABN Amro puts it, "we see Spanair facing major challenges this year, with the growth of Vueling, Clickair, easyJet and Ryanair in the Spanish market, while airBaltic would be threat–ened significantly were Ryanair to open a new base in Riga".Adding to the problems that the mainline and the "other" carriers face is the Group’s financial position. It is getting better: long–term debt totalled SEK 17bn (€1.9bn) at the end of March 2007 (SEK 5.9bn down on a year earlier), although cash and short–term investments at the end of Q1 2007 were SEK 8.8bn, almost identical on a year earlier. The debt improvement came from the hotel transaction and other sales (+SEK 3.8bn in 2006), stronger cash flow (+SEK 3bn), and the sale of aircraft and other property (+SEK 4bn). But Jansson says that although the 2006 result is encouraging, group revenue is "too low to meet shareholders' return requirements and future investment needs".

| Fleet | Orders | |

| Scandinavian Airlines | ||

|---|---|---|

| A319 | 2 | 2 |

| A321 | 8 | |

| A330 | 4 | |

| A340 | 7 | |

| 737-400 | 4 | |

| 737-500 | 13 | |

| 737-600 | 26 | |

| 737-700 | 15 | 2 |

| 737-800 | 13 | |

| MD-81 | 4 | |

| MD-82 | 31 | |

| MD-87 | 9 | |

| F50 | 6 | |

| RJ-70ER | 1 | |

| Q400 | 23 | |

| Total | 166 | 4 |

| Spanair | ||

| A320 | 16 | |

| A321 | 5 | |

| MD-81 | 1 | |

| MD-82 | 10 | |

| MD-83 | 17 | |

| MD-87 | 11 | |

| F100 | 2 | |

| Total | 62 | |

| Wideroe | ||

| Q100 | 17 | |

| Q300 | 8 | |

| Q400 | 3 | |

| Total | 28 | 0 |

| Blue1 | ||

| MD-90 | 3 | |

| RJ-85ER | 7 | |

| RJ-100ER | 2 | |

| Total | 12 | 0 |

| airBaltic | ||

| 737-300 | 2 | |

| 737-500 | 8 | |

| F50 | 9 | |

| Total | 19 | 0 |

| SAS Total | 287 | 4 |

This is directly affecting the fleet plan. The Group fleet consists of 287 aircraft, (see table, left) but the average age is approaching 11 years, with wide variation among the Group’s airlines. airBaltic’s fleet is 15 years' old, while Scandinavian Airlines' average age is just under 11, with Blue1 having the youngest age, at less than seven years.

Yet the Group has just four aircraft on firm order, all for delivery in 2007, and costing the Group just $109m in capex commitments. What the Group calls a "capex holiday" will continue through to the end of the decade, i.e. there will be no major investment in aircraft in this period. On short- and medium–haul, this has forced the Group to keep its fleet of 83 MD–80s (44 of which are with Scandinavian Airlines, with 39 at Spanair) — and which have an average age of almost 18 years — for at least another five and possibly up to eight years, until they are replaced by a new generation of aircraft.

SAS Group had been expected to replace these aircraft in 2008 or 2009, but the Group spin on this about–turn is that although the MD–80 fleet has high fuel burn compared with modern aircraft, in other areas they are relatively cheap to run (e.g. in maintenance). The decision to postpone will have a particularly negative effect on Spanair, which had wanted to phase out all its MD–80s by 2010 at the latest, and which had already announced plans to start replacing the model via the lease of 717s and A320s this year. Instead, Spanair now has to follow the fleet restrictions imposed by its parent.

Elsewhere in the Group fleet, the MD–90s have been phased out of the Scandinavian Airlines fleet and reassigned to the other Group airlines.The SAS Group estimates it needs up to 50 new regional aircraft across its airlines. Yet again — as with the medium–haul aircraft — financial constraints have overridden operational requirements. Around 25 regional aircraft are needed for Spanair, and other aircraft are needed for Blue1, airBaltic and Estonian Air. Although an order is not imminent in the short- or medium–term, SAS Group says that the Sukhoi Russian Regional Jet is "very interesting".

Time to be radical

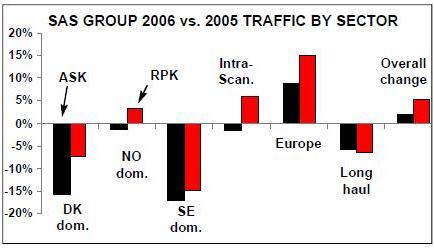

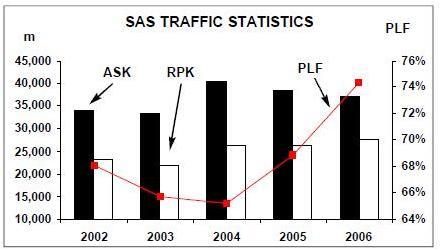

In 2006 the Group sold and leased back 19 aircraft, but the scope to save more money from this is reducing fast, as just 20% of the total Group fleet remains owned, with the rest all now leased. The Group’s overall airline strategy can be seen in the traffic chart. In 2006 SAS Group passengers carried rose 6.3%, to 38.6m (of which 25.1m were carried by Scandinavian Airlines), and a Group RPK rise of 5.4% was higher than a 1.9% increase in ASKs, resulting in a 2.4% rise in Group passenger load factor, to 71.5%. However, there was wide variation in ASK adjustments among different geographical areas, with capacity increases in Scandinavian–Europe and intra Scandinavian routes coming at the expense of long–haul and Swedish domestic capacity.

In 2007 the overall capacity increase will rise to 5%-7%, but most of that growth will come from subsidiaries, with 15% expected at Spanair, 20% at Blue1 and 30% at airBaltic. After two years of contraction (see chart) Scandinavian Airlines'overall capacity will remain flat in 2007, with the Danish operation level, Braathens up 2% and Sweden up 6%. Long–haul capacity, however, will fall by an anticipated 4% in 2007.

Based on this capacity rise, combined with falling costs, a continuing recovery in traffic and a reduction in the price of fuel, many analysts are upbeat about the Group’s prospects. Group results for the first quarter of 2007 revealed a 6.7% rise in revenue, with a reduced operating loss of SEK 327m, equivalent to €36m (SEK 1.1bn in Q1 2006) and the net loss falling from SEK 1.1bn in January- March 2006 to a loss of SEK 47m (€5.2m) in Q1 2007.

Yet the Group is still weak strategically. The 2006 results prompted SAS Group to launch a strategic review aimed at identifying further cost–cutting and opportunities to increase revenues, and the so–called "Strategy 2011" — which is being unveiled this June (having been delayed from May) — will aim for "conceptually driven restructuring" according to Jansson.

Undoubtedly this will include yet another raft of cost cutting (and unions appear to sense what is coming), although this will be wrapped around a justification of strategic readjustment. "Strategy 2011" will define some big questions, says Jansson, but no radical departure from the current geographical and customer focus is expected, nor necessary.

Where Jansson may be more radical is in defining the scope of the SAS Group. As far back at the 1990s it was clear that the SAS Group’s attempts to diversify into a full travel company (the so–called Total Travel Concept) was a failure, yet the Group still held on to many non–aviation assets for far too long, for example only disposing of its major hotel chain last November.

SAS Group says it has completed its disposal programme and, according to Jansson, is now "a company of core operations", but surely this depends on what you consider is core. If this is defined as aviation assets, then certainly SAS has (at long last!) a core of aviation concerns only — but Jansson has to go further than that, and ask questions as to whether it has the right aviation assets.

Most obviously, SAS’s remaining 20% stake in bmi (it sold another 20% stake in 1999 to Lufthansa) — which the Group maintains has always been a financial investment and not held for strategic reasons — will probably go at the end of 2007, once the SAS Group finally escapes from its disastrous joint venture agreement with bmi and Lufthansa. The European Co–operation Agreement (ECA) was signed in 2000 and shares revenues and costs on routes between the UK, Scandinavia and Germany, but all ECA does is rack up losses for SAS and Lufthansa. ECA has been described by SAS as "a stupid contract", and the Group’s share in ECA cost it SEK 415m in 2006, with the accumulated figure since ECA started rising to SEK 2bn (€220m) as at the end of 2006 (and with another year of losses to add in 2007, the ECA’s last year of operation).

UK sources say that SAS Group is already touting its bmi stake around airlines and private equity groups (including Iceland’s FL Group, according to one UK newspaper), for a price in the range of £100m. But while Virgin Atlantic and British Airways may well be interested in buying Sir Michael Bishop’s 50% plus one share stake when he retires, the attractiveness of a minority stake in bmi must be far less, even if bmi’s 13% share of Heathrow slots is a prime asset given the recent Open Skies deal. Lufthansa, with a 30% stake in BMI, is the most obvious acquirer of SAS’s stake, but the German flag carrier appears more interested in buying airlines in southern Europe.

Intriguingly, in his conversation with analysts after the 2006 results were presented in February this year, Jansson stated that what SAS does is still "a little bit complicated. I am used to working in one or two parts of the value chain, but SAS works in three different parts of the value chain — the pure airline operation in nine different subsidiaries, ground handling in another subsidiary, and then technical services”. "We now have a core operation in the Group, but we also have to look into it more in detail, and define what the core, core operation is, and what consequences it could have for the Group for the future."

While Jansson may well have been cautious in what he was saying prior to the unveiling of the formal strategy review, "Strategy 2011" may be his ideal — and only — opportunity to be truly radical. And that should mean SAS Group being brave enough to dispose of more parts of the SAS empire .

ABN Amro says that it "has doubts about the sense of running a relatively small–scale heavy maintenance business in the high–cost Nordic area, which cannot compete with the business scale of companies such as Lufthansa Technics or the labour costs of Iberia." Indeed the futures of both Ground and Technical Services must be in great doubt — they contribute little or nothing to financial results, employ a vast amount of capital, and could easily be replaced by a series of outsourced contracts.

But Jansson must be even more radical that that. The Group’s "other" airline operations are spread around Europe, with moderate or little synergies between them. ABN Amro sees "no sense in SAS owning Spanair, and we are pretty sceptical about Blue 1". What real feed these airlines provide into SAS’s routes out of its hubs is open to question, particularly as SAS wants to de–emphasise its hubs and build up more direct routes. The sale of Spanair (and speculation is mounting that Lufthansa may make an offer), Blue1 and — potentially — all its other non–mainline carriers would be a strategic and financial blessing to SAS, freeing up much needed resources to bolster its core mainline operations that are facing ever–increasing competition from the LCCs. And an argument can even be made for SAS to ditch its entire long–haul operation, which is tiny compared with that of any of the other European majors.

Following a restructuring of ownership in 2001, 50% of the Group is held by the Scandinavian governments — the Danish and Norwegian states each own 14.3%, and Sweden owns 21.4% — with the other 50% listed on the Nordic Exchange in Stockholm. In the past, Scandinavian government ownership has tended to moderate any managerial desires to be truly radical, but substantial cracks are now appearing in that unified Scandinavian viewpoint.

In particular, Sweden’s new right–wing government says that it wants to sell off its stake in SAS at some point in the future, as part of a huge multi–billion Euro sell–off of state assets, when restructuring has been completed. In March the Danish government insisted it would not sell its stake in SAS — for the moment at least — as it wanted to give time to the new CEO to turn the group around. However, some elements in the Danish government — and in particular within the Finance ministry — are believed to have different views on this. The only unswerving commitment to retain its SAS stake comes from the Norwegian government, which (off–the–record) is critical of the Swedish government’s position on SAS, which it believes is motivated purely by ideology.

There’s little doubt that SAS Group benefits from its ownership by the Scandinavian governments. Last year — after a formal tender process — Scandinavian Airlines won the vast majority of lucrative contracts on offer to carry Danish government officials for the next two years (and worth an estimated €25m), and also tied up a similar deal with the Swedish government. But loyalty from state owners will dissolve at some point, and when it does the SAS Group will be in danger of being disassembled by new owners. For the last six months speculation has been growing about a potential Lufthansa bid for SAS Group — which has encouraged an upwards drift in the SAS share price — although Lufthansa says these rumours are "speculation".

But much more ruthless predators (for example, private equity groups) are likely to be looking at the SAS Group, and if they acquire the company they will not hesitate to carve it up. The question is, will SAS Group’s current management be brave enough to be that ruthless now?