The Big Three Chinese airlines: the great leap forward to come

October 2003

It has been a terrible 12 months for the Chinese airline industry. Just after the effects of September 11 had faded away, along came Gulf War II and — most devastating of all — the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) crisis.

Though passengers started falling off in March, the worst effects of SARS were felt in May and June of 2003 after the Chinese government admitted it had an epidemic on its hands. At its peak, the SARS crisis virtually halted all business and tourist traffic to China. Although the Chinese government gave temporary tax breaks to Chinese airlines and cut navigation and landing fees by 20% to both Chinese and foreign airlines for a limited period, profitability at Chinese airlines collapsed, forcing the Big Three — Air China, China Southern and China Eastern — to plan bond issues in order to secure short–term funding. The airlines slashed services and costs as a temporary response but, soaring oil prices due to the Gulf War and the SARS crisis meant that red ink appears all over Chinese airlines' P&L accounts for the first half of 2003.

Chinese airlines, however, appear to be recovering well in the second half of 2003, and the SARS effect on traffic disappeared by August at most of the country’s airlines.

Recovery has been slowest at airlines based in the areas most affected by SARS — Beijing and Tianjin as well as the provinces of Guangdong and Shanxi — but even here airlines are confident traffic will be back to normal by the end of September.

Traffic recovery comes on the back of growing confidence in the airline industry now that the Chinese government (in October 2002) has finally approved the long–anticipated Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) restructuring plan for the industry, consolidating seven smaller airlines under the control of the traditional Big Three.

The move was designed to cut out unnecessary domestic competition, enable economies of scale and allow a reduced number of carriers to compete against growing competition from carriers such as United and Cathay Pacific. The Chinese government is also pressing ahead — slowly but surely — with liberalisation both internally (e.g. by allowing airlines greater freedom to raise or discount fares and permitting Chinese companies to invest in airlines) and externally (e.g. by signing liberal ASAs and granting fifth freedom rights to selected foreign carriers).

Despite SARS and the Gulf War, there are still impressive growth forecasts for air traffic within and to/from China. The CAAC is forecasting that the country’s airline traffic will grow at around 10% per year in the current decade and that Chinese airlines will carry 140m passengers and 30bn tonne–km annually by 2010. While this forecast is not as bullish as those made a couple of years ago (and Boeing and Airbus’s forecasts are more conservative) there is little doubt that the Chinese aviation industry will still undergo some of the fastest growth rates in the world over the next few years. In addition, the World Tourism Organisation estimates China will become the world’s top tourism destination by the year 2020.

By 2010 the CAAC estimates the Chinese fleet will almost double, to 1,250 aircraft, while the Aviation Industries Development Research Centre of China forecast (pre–SARS) that Chinese airlines would order 1,762 aircraft in the next two decades. As much as a third of this fleet growth will be in regional jets since the CAAC is keen to encourage a hub and spoke network though China, with regional airlines feeding in traffic to the Big Three at the major cities.

Altogether the Chinese fleet currently comprises 785 aircraft, 59 more than in 2002 due to a steady trickle of deliveries despite the SARS crisis. Today there are 79 outstanding orders, down on the order book of107 a year ago. 49 of these orders are for Airbus aircraft, emphasising the increasing success Airbus is having in the market, though this may as much to do with geopolitical issues as business matters. Given the Chinese government’s unease at the Gulf War, Airbus’s market share may grow even faster in the next few years.

Boeing’s order book currently stands at 24, and Russian aircraft dominate the balance of today’s orders.

Under the CAAC plan, Air China is now merging with China National Aviation/Zhejiang Airlines and China Southwest; China Southern is combining with China Northern and Xinjiang Airlines; and China Eastern is taking over China Northwest, Yunnan Airlines and Air Great Wall. Other than Air Great Wall however, none of the mergers have yet been completed, and they will not do so until well into 2004, when their names will finally disappear.

Since last year’s survey three new airlines have appeared — Air China Cargo (see Air China section below), CR Airways and Yangtze River Express. CR Airways is a former Hong Kong–based helicopter operator that has received permission to operate a CRJ200 in early 2004, while Yangtze River Express is a dedicated cargo airline that launched in January 2003 with three 737- 300s. Yangtze is part owned by Hainan Airlines and the Shanghai Airport Group, and has signed a freight distribution contract with UPS. While further start–ups are bound to emerge over the next few years in China, at the same time many of the existing regional carriers are likely to be swallowed up by the Big Three.

Our commentary below does not include the Hong–Kong airlines — Cathay Pacific and Dragonair, who earlier this year fought a bitter legal battle (which Cathay won) over Cathay’s plans to launch operations to three mainland Chinese cities — Beijing, Shanghai and Xiamen. Though Dragonair is minority–owned by Cathay and Swire Pacific, the largest single shareholder (with 43%) is the China National Aviation Company (CNAC), which is owned by the China National Aviation Corporation (owner of Zhejiang Airlines and now part of the Air China group).

Air China

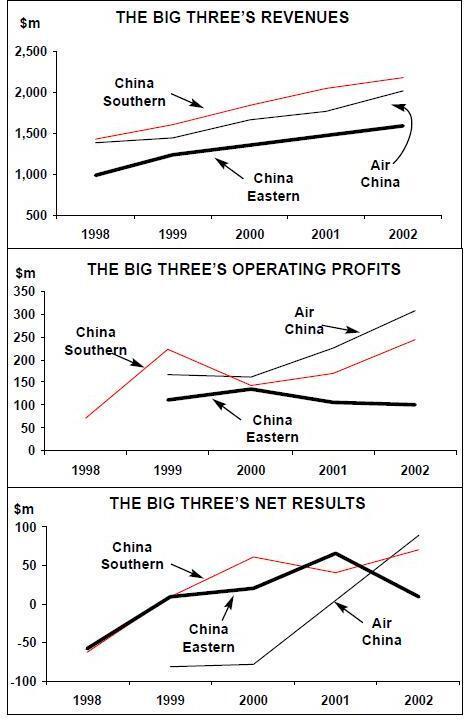

Air China has not released financial results for the first–half of 2003, but because of its Beijing base the airline was hit hard by the SARS crisis and is almost certain to have recorded a net loss for the period similar to, if not worse, than those of its Big Three rivals. In 2002, Air China posted a net profit of $89m (compared with a $5m net profit in 2001), based on revenues of more than $2bn.

Air China had been planning an IPO in 2003, but the SARS crisis meant the listing had to be postponed. It has been reported that Air China may get a "backdoor listing" by buying a 20% stake in Ji Nan–based Shandong Airlines — which is listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange — and a 26% stake in the airline’s unlisted parent, the Shandong Aviation Group. But Air China’s interest in Ji Nan–based Shandong Airlines is to secure regional feed from the airline, which has a 26–strong fleet of Bombardier, Saab and 737 aircraft but is believed to be loss making. Air China’s long–term strategy is still to get a direct listing on a main exchange, and more immediately it is pressing ahead with plans to issue up to $350m worth of bonds in order to secure short–term funding.

Air China employs 23,000 staff and has a fleet of 73, all of which were Boeing aircraft until recently. Air China received its first A319 in July, one of 11 that will be delivered by the end of 2004 as part of an overhaul of its short–haul fleet. Most of these are destined for Zhejiang Airlines, now a subsidiary of Air China. The A319s were ordered last year as a replacement for a cancelled order of A318s due to problems with the development of Pratt & Whitney engines, but nevertheless this represents an important step forward for Airbus in China, a market traditionally dominated by Boeing. Air China may order further A319s, it is believed, and earlier plans to postpone deliveries, considered at the height of the SARS epidemic, have now been dropped.

The airline has more international routes than any of its Chinese competitors and there has been intense speculation as to which global airline alliance Air China will join. Air China’s deteriorating relationship with Northwest (see the China survey in Aviation Strategy, October 2002) was formally terminated in June this year, and in August Air China signed a code–sharing and frequent–flyer alliance with United, thus edging the Chinese carrier even closer to the Star camp. Star is keen to encourage Air China to become a fully–fledged member of the global alliance, plugging a perceived "China gap" that still exists even though South Korean–based Asian Airlines — which operates to 12 Chinese destinations — joined Star in March. A successful Air China tie–up with United to follow an already–profitable code–sharing deal with Lufthansa since 2000, may well persuade Air China to take the plunge sooner rather than later.

In March 2003 Air China launched a new cargo subsidiary — Air China Cargo — in which it owns a 51% stake, the remainder belonging to Hong Kong–based conglomerate CITIC Pacific (25%) and Beijing Capital International Airport (24%).

Air China Cargo has taken over all of its parent airline’s cargo operations, which comprised four 747- 200Fs, but has plans to increase its fleet. In 2004 and 2005 three Tupolev Tu–204Fs will be delivered to Air China Cargo, the legacy of a China government order in 2001 for China Southwest Airlines, now part of Air China as a consequence of the CAAC consolidation plan. In addition, in September 2003 Air China Cargo leased a 747–400F from SIA Cargo for three years, and another 747–400F may be leased or bought in early 2004. Air China Cargo expects to earn around $0.5bn in revenue this year, and become one of one the largest cargo airlines in the world within a few years.

China Eastern

Shanghai–based China Eastern, the first Chinese airline to be listed abroad (in Hong Kong and the NYSE), has been badly affected by SARS and the Gulf War.

At one point, rumours of huge losses due to the SARS crisis led to China Eastern’s shares being suspended from the Shanghai and Hong Kong exchanges, though they were quickly reinstated.

When they were eventually revealed, the losses were large. In the first half of 2003 China Eastern made a $151m net loss, compared with a $3m net profit in January–June 2002. This was despite the Chinese government’s help in the form of tax and infrastructure charge exemptions (which China Eastern is lobbying hard to be extended until the end of 2003) that benefited the airline’s bottom line by $30m in the first–half of 2003.

Revenue fell 8% over the six–month period, to $661m. Passenger RPKs fell 20% in the first–half of 2003, though there was a significant difference between domestic RPKs, which fell 8%, and international RPKs, which fell 29%. Interestingly, cargo traffic was totally unaffected by the crises, with cargo revenues up 30% over the half–year period — a reflection of the Shanghai region’s underlying economic boom. Yet the disappointing first–half 2003 figures came on the back of a bad 2002, when China Eastern reported a $10m net profit, substantially down on 2001.

May traffic was the worst affected by the SARS crisis, being 84% down on the same month in 2002 and way ahead of 30% plus capacity reductions made by the airline on some routes. In June, traffic was 47% down but July traffic returned to pre–SARS levels domestically — which was much quicker than the airline anticipated — though international traffic was still some 42% down in July.

China Eastern operates an 87–strong fleet and has the largest order book of any Chinese airline — 22 deliveries are outstanding, 20 of them Airbuses. Initially the SARS crisis forced China Eastern to defer its outstanding deliveries due in 2003, but quick recovery since the epidemic ended has encouraged the airline to return to almost the same delivery schedule as existed pre- SARS.

Ten new aircraft will be delivered between now and the end of 2003 and the 22 outstanding orders will cost the airline around $17bn according to Luo Weide, China Eastern CFO. So far this year China Eastern has received two of its order for five high–capacity A340–600s, which will replace MD11s on long–haul operations to North America, and the remainder will be delivered by the end of 2003. The MD11s are being transferred to cargo subsidiary China Cargo Airlines, which operates regionally and to the US. Seven A320s will be delivered to China Eastern in the remainder of 2003 and 10 more through 2004–2005. The airline also has two Tu–204–120Cs on order.

In August 2002 China Eastern bought Wuhan Airlines, a regional carrier that today has a fleet of nine aircraft, eight of them 737s. Wuhan was a member of the China Sky Aviation Enterprises alliance along with five Chinese regional airlines, but since two of the other members are now associated with China Southern this independent alliance is effectively dead.

China Eastern still has to complete the complicated takeover of China Northwest and Yunnan Airlines, as designated by the CAAC, since the two airlines have initially been acquired by China Eastern’s parent company. Before the three airlines can be merged a complicated asset valuation process has to be completed, for which China Eastern has hired Morgan Stanley to assist it. In addition, China Eastern’s formal purchase of the two airlines from its parent will have to be financed by some combination of equity issue and/or corporate bonds, a process that the airline says will be completed by the end of 2003.

China Southern

Guangzhou–based China Southern saw its profitability wiped out by the crises that hit China this year. For the first half of 2003 it recorded a net loss of $150m, compared with a net profit of $15m in the first half of 2002, while revenue fell 21% to $821m.

Domestic RPKs fell 26% over the half–year and international RPKs were down 31%. For the full year 2002, China Southern posted net profits of $70m, 69% up on September- 11 affected 2001 and based on a 7% rise in revenue.

Guangzhou was at the heart of the SARS epidemic and there was little the airline could do to at the height of the crisis. After cutting international capacity by up to 80% and domestic routes by almost 50%, June RPKs were down 62% on June 2002.

However, the airline appears to be recovering quickly — the July RPK figure was just 14% down on the year before, and traffic is forecast to be back to normal in August and ahead of last year in September. The recovery will be helped by the launch of China Southern’s online ticket sales operation which it expects to sell more than 10% of all tickets sold during 2003.

China Southern has a fleet of 100, making it the largest airline in China. Boeing has the largest fleet share, with 67 aircraft, and there are also 24 A319s and A320s. Like the other Big Three members, at the height of the SARS crisis China Southern considered deferring aircraft deliveries, but decided to keep to the original delivery schedule once the SARS effect died down (and in order to escape punitive delay/cancellation charges). Currently there are 10 outstanding orders, for nine 737- 700/800s and one 777–200ER, which will be delivered by 2005. The new 737s will replace older 737s currently on operating leases.

These orders will be partly funded by the 1bn shares China Southern issued in July 2003, equivalent to 22.86% of issued share capital, which raised a total of $300m. At the start of 2003 the airline was planning to raise almost twice that figure from the equity issue, but the SARS crisis affected the amount it could raise. The $300m will also be used partly to pay off some long–term debt, the airline says.

In its prospectus for the new shares, China Southern forecast a $25m net profit for full year 2003, compared with a $62m net profit in 2002.

However, this forecast was prepared under Chinese accounting standards, which tends to produce figures lower than those reported under international accounting standards that Aviation Economics uses in the graphs on page 17.

Once China Southern completes the integration of China Northern and Xinjiang Airlines, it may look to acquire regional feeder airlines.

In 2002, China Southern bought a 49% stake in China Postal Airlines for $18m and a 39% stake in Sichuan Airlines for $16.5m. The latter deal is intriguing in that at the same time Shanghai Airlines and Shandong Airlines also each bought a 10% stake in southwest–based Sichuan, which has a fleet of 15 A320s, A321s and ERJ–145s. This deal finally broke China Sky Aviation Enterprises, the independent alliance of Chinese airlines that included Shanghai and Shandong. Between them, Shandong and Shanghai operate a fleet of 54 aircraft along the east of the country and are the largest remaining independents after Hainan Airlines (see below).

But the informal alignment of Shandong with China Southern may not be too long lasting, as Air China is reported to be trying to "steal" Shandong away by buying a stake in the airline (see Air China section).

The others

SARS and the Gulf War also hit Hainan Airlines, mainland China’s fourth largest carrier with a fleet of 50 aircraft, even though the southern island province of Hainan was not directly contaminated by SARS. Traffic fell by 80% during the crisis, helping Hainan Airlines post a net loss of $118m in January–June 2003, compared with a $7m net profit in the first–half of 2002. Revenue fell 14% in 1H 2003.

However, traffic has bounced back since July and further good news may be on the way for Hainan Airlines with CAAC discussions over declaring an "open–skies" policy for the Hainan province, which would bring competition from non–Chinese airlines on international routes. The CAAC’s reasoning is that open skies would bring more tourist traffic to the traditional Chinese holiday island, since currently most flights to the island operate from the Chinese mainland. Open skies would allow foreign airlines to bring in tourist traffic to Hainan, but forbid them from flying on to the mainland, thereby theoretically providing new passengers for Hainan Airlines.

Now that the SARS crisis is over and with open skies on the horizon, Hainan Airlines will be looking to get back into profitability quickly, building on the 2002 net profit of $16m and 2001 net profit of $7m. On the downside, increasing competition from the Big Three is bound to have a negative effect on profit growth.

For China’s remaining airlines, the future looks bleak. Once the Big Three consolidate the airlines assigned to them as part of the CAAC master plan, they will exert an even stronger grip on domestic aviation, directly accounting for 439 aircraft (56% of all aircraft in China) and 52 outstanding orders (66% of all Chinese orders).