Is the traditional Big Hub model still viable?

Jul/Aug 2002

The US industry is in the midst of its second financial disaster in ten years. The losses of 2001 ($10 bn operating, $7 bn net, even after federal subsidies) are not likely to abate significantly in 2002, with net losses of $5 bn likely. Economic value measures (return on capital minus cost of capital) also indicate a crisis measured in tens of billions. As the economic collapse is almost exclusively with carriers operating traditional Big Hub based networks (American, United, Delta, Northwest, Continental, US Airways and America West), the long–term viability of this business model is under challenge for the first time since deregulation.

Are Big Hub carriers on the road to financial recovery?

The central question is what will be required for these carriers to achieve a full turnaround, restoring sustainable financial returns. As yet there is no consensus even on the causes or seriousness of the crisis. Two diametrically opposed views have emerged.

The first view argues that the 2002 crisis is very similar to the 1992 crisis, and while challenging, the turnaround process will not require radical, structural change and should be manageable with full recovery possible within two, perhaps three years.

The second argues that the 2002 crisis is different from all previous crises, that the Big Hub business model is fundamentally broken, and only the non–hub "Quasi–Network" model primarily associated with Southwest will drive future financial returns. This implies that large portions of the Big Hub sector are unsustainable, and that the industry may be facing far more painful upheavals than it has ever experienced, and that the industry’s current response to the crisis has been the proverbial rearrangement of the deck chairs on the Titanic.

Although the broader issues may be relevant elsewhere, the discussion of the viability of hub airlines will be limited here to the specific market and operating conditions of the US domestic environment. One should not assume direct parallels with hub competition in Europe or elsewhere.

Is 2002 largely a rerun of 1992?

There are certainly broad similarities between the two crises.

- Both were proceeded by a dynamic period of change and profit improvement (mid 80s/90s) which in turn spurred major fleet expansion across the industry.

- Both dramatic collapses were accelerated by external shocks (Gulf War, September 11) and recession.

- Both featured major price wars that predated the external shocks.

- All Big Hub carriers experienced enormous losses, while Southwest maintained marginal profitability.

- Within the Big Hub sector, certain carriers faced liquidity/balance sheet crises.

The "manageable crisis" view notes that hubs have worked successfully for decades, and points out that the mid–90s recovery did not require any changes to the basic industry structure or business model. If one can infer a plan from the recent actions and statements of these seven carriers, financial recovery can be driven by:

- Serious belt tightening (capital freezes, recent layoffs, cost–cutting exercises);

- Big labour concessions (facilitated in some cases by the ATSB or Chapter 11);

- Aircraft lessor haircuts;

- Industry consolidation, focused on eliminating capacity of the "weaker" carriers; and

- An eventual rebound of business traffic, as the business cycle improves.

Unfortunately, this view is based on a flawed understanding of what actually drove the mid–90s recovery. When the Gulf War collapse first occurred, this type of approach failed. Short–term belt–tightening, labour concessions and cost–cut–ting needed to occur, but they did not generate billions of improvement then, and today there is less obvious fat that can be quickly cut. The 92 collapse had not been caused by either wasteful spending or extravagant labour agreements. While some argued that the split of financial returns between capital and labour was out of whack, industry profitability recovered nicely in the mid–90s without any lasting changes in that area.

The "obvious" solution in 1992 was to "let market forces work", and punish those carriers who had proven incapable of running profitable airlines- Northwest, Continental, America West and TWA–so that the "better run" airlines with the stronger balance sheets could earn a reasonable return. Of course events proved that this view was completely wrong. Northwest and Continental proved to be the most profitable airlines of the 90s, and it was "strong" carriers like American that had unprofitably expanded in the late 80s and needed to shut down failed hubs. There was no relationship between the long–term competitiveness of an airline’s network and its liquidity or balance sheet when the collapse deepened.

What really drove the 92 turnaround?

The 92 turnaround did not result spontaneously Four factors were key.

• Five years of industry- wide zero growth during 1990-94.

This followed the late 80s expansion, led by American, United and Delta, that presumed that earlier productivity–driven gains (new yield management tools, post–deregulation hub expansion, A/B wage scales, the decline of carriers like Eastern and Pan Am) would continue and ignored normal business cycle risks.

• Major restructuring of failed network investments.

Some 30 weak hubs shutdown or were significantly downsized (Raleigh–Durham, Milwaukee, Cleveland) with assets moved to more productive uses (Dallas Ft Worth, Detroit, Newark).

• New investors driving tangible improvements.

New equity investment was not huge, but "kick–started" the turnaround process, led by KLM’s willingness to speculate on an Northwest turnaround, which in turn facilitated the "investments" from the Northwest labour groups. KLM added significant tangible value by developing a North Atlantic alliance, as did BA with its investment in USAir. In addition to equity, Texas Pacific made major improvements in the service culture and RASM performance at Continental.

• New industry-wide/longer-term approach to capacity growth

Certain carriers, led initially by American and Northwest (and strongly reinforced by Wall Street) proactively pushed for a new industry–wide focus on profits rather than market share and growth. Price stability was restored once the new focus on the overall supply–demand equilibrium took hold.

Had key participants not made bold, highly risky moves (in particular KLM and the ALPA and IAM groups at Northwest) it is quite possible that the destruction of viable assets would have been far greater, and the eventual recovery would have been slower and more difficult.

Can the 1992 approach work again in 2002?

It is clear that a 2002 turnaround will also require some type of major, structural improvements — short–term cuts and hoping for a business traffic recovery certainly won’t drive a recovery. But it would appear that the conditions are much less favourable to serious reform than they were in 92.

- No obvious network restructuring potential. Unlike the early 90s, there are no hopelessly uncompetitive hubs left to close, and major distribution cuts are already in place.

- Growth of Southwest and others. Southwest was 2% of industry in 92, and there was no funding for JetBlue–type new entrants with aggressive growth plans in the early 90s.

- Overcapacity/pricing collapse worse than 92 Today’s supply–demand imbalance is driven by over–expansion during the greatest economic bubble in history, followed by post–September 11 demand drops that were much greater than those during the Gulf war; unlike 92 an absolute decline in business traffic has been observed, raising new concerns that traditional pricing approaches are fundamentally "broken".

- No major new investors on the horizon There is a fundamental shift in investment away from traditional Big Hub airlines to airlines following the Southwest–type Quasi–Network model.

Does the low-cost model make the Big Hub model obsolete?

Southwest has maintained strong growth and returns by following a completely different business model, avoiding most traditional network and distribution approaches, and achieving much lower unit costs than the Big Hubs. Has the historic market share fight between the old–line majors been superseded by a battle to the death between the two airline business models?

The "Big Hubs are obsolete" argument starts with Southwest’s cost advantage and superior financial performance and notes the growing ability, across the economy, for new business models to rapidly overwhelm long–standing traditional models. Common examples include Home Depot (who rendered the local hardware store obsolete), and Walmart (who overpowered department stores and other traditional retailers).

But are Southwest, JetBlue and the other Quasi–Network carriers really going to follow in the path of Walmart/Home Depot, eventually dominating the industry? Or will they be a bit more like Toyota and Nissan entering the US market: profitably capturing a share of the industry, weakening but not destroying the viability of traditional carriers, who thus will still carry the majority of all traffic?

Big Hub airlines are low cost airlines in many markets

Business models work if they create sustainable competitive advantage–meaningful cost advantage or greater customer value. The Big Hub model obviously did both for many years, and on paper at least, there is no reason it could not continue to do so for many years.

Big Hubs are the lowest cost way to establish a very large network serving thousands of O&D markets. They are far and away the lowest cost way to serve markets with limited traffic that cannot support multiple jet frequencies purely with local traffic. Hubs have grown successfully because the overwhelming majority of aviation markets fall into this category. Hubs are also highly effective in maximising service in one city (Dallas–Fort Worth, Detroit, etc) and hub carriers usually have an advantage serving markets with complex product or distribution requirements (such as first class or international traffic).

It is less appreciated that while Big Hubs have a significant cost advantage serving many markets, they do not have a cost advantage in all markets. Large hub networks can exploit real strengths, but a ubiquitous network must expand into O&Ds where cost advantage is limited or nonexistent.

As with any other sensible business model, certain conditions must be met if the natural competitive advantages of a Big Hub are to be profitably exploited, and certain risks must be carefully managed. Big Hubs specifically require:

- Mixed fleets (in order to tailor capacity to widely varying demand levels);

- Complex systems (to manage variety, volatility of markets and products);

- Major price discrimination (to capture the value created when a superior schedule is provided); and

- Very large operating scale (to cover these high initial airport and complexity costs).

The core customer is the frequent business flyer, who might value the high quality schedules Big Hubs can efficiently produce. However, fares must be kept in line with the level of value these customers receive (or perceive), and capacity must be in line with the revenue potential of this core market. Fill–up leisure traffic can be priced at marginal rates, but it is impossible to profitably invest capital to expand capacity for marginal, fill up demand.

Since the marginal cost of producing an incremental unit of capacity is very low, Big Hub airlines face greater risk of overcapacity. Historical practice suggests that revenue is usually maximised by increasing yields while constraining supply, which suggests that volume growth is difficult to achieve unless exogenous business travel demand is growing, or productivity improvements permit price stimulation.

While the higher costs of mixed fleets and complex systems are often seen as a critical flaw in the model, they are actually the key to serving more markets at lower cost and with greater flexibility.

With managers and systems designed to cope with complexity and volatility, Big Hub carriers should be more adept at coping with marketplace changes.

Quasi-Network airlines only have lower costs in certain markets

The Quasi–Network approach is the lowest cost way to serve very high–volume O&Ds, and to serve medium sized O&Ds where Big Hub carriers do not have clear advantage (O&Ds to major hubs). This model was originally developed by PSA in the 1960s but is closely associated with Southwest. The Quasi–Network model is not designed to serve all markets, could not provide the basis for a comprehensive domestic network and would be an extremely high–cost operation in small markets. Multiple business models coexist in most industries, each powerful in a certain segment, but unable to dominate every market.

The Quasi–Network model has a number of key requirements, including maximum fleet standardisation and utilisation, maximum product/distribution simplification and more limited price discrimination (focus more on share shift/stimulation) among others. Quasi–network carriers must avoid high cost airports, as high fees and congestion can quickly undermine the cost advantage. With fewer scale economies than a Big Hub carrier, growth becomes more expensive. Facing Big Hub carriers with very low marginal costs, Quasi–Network carriers face greater risk of predation.

Where do the two models have "natural" advantage?

In the midst of the early 90s crisis, concerned about the future growth of Southwest, and anxious to refocus on "strength" markets, one of the Big Hub airlines attempted to estimate the size of the markets where each of the two models had competitive advantage.

Big Hubs were found to have advantage in O&Ds accounting for 70% of 1993 demand, including all O&Ds to/from the largest hub cities (Dallas Ft Worth, Detroit, Pittsburgh) and O&Ds too small to support multiple nonstop jet frequencies but where hub connections are geographically convenient (Jacksonville- Boston, New Orleans–Seattle, Milwaukee- Syracuse). "Quasi–Network" carriers were estimated to have potential competitive advantage for 20% of domestic traffic, covering high demand O&Ds that could support multiple nonstop jet frequencies (San Jose–Los Angeles, Baltimore–Orlando, Las Vegas–Kansas City), but excluding O&Ds at either the top hub airports or the highly congested Northeast airports. 10% of domestic traffic was in O&D where neither model had a clear advantage, including high–demand markets with complex product or distribution requirements that Southwest historically avoided (Hawaii, Caribbean) or low–demand O&Ds not well served by large hubs.

While an updated analysis would produce different results, the finding that Big Hub carriers have natural advantage in serving a large majority of domestic traffic flows is undoubtedly still valid.

In 1993, a major (although obvious) finding was that Southwest could comfortably plan on many, many years of profitable growth. Southwest was only 2.5% of the industry in 1993, and had the "Quasi–Network" segment all to itself at that point. It could make enormous investments in new aircraft with only a fraction of the uncertainty fleet planners at United or Delta faced. The more difficult challenge was how to prioritise their many promising network opportunities.

More importantly (although equally obvious) was that Big–Hub carriers would inevitably lose some of their current 93% share, with shrinkage to a 70–75% share possible. There were also nine majors fighting over this segment, adding significantly to volatility and the risk of future fleet investments. Capacity plans needed to recognise the inevitable loss of share to Quasi–Network carriers, and could not assume the market dominance of the 1980s as an absolute birthright. Similarly, when Toyota and Nissan entered the US car market with an efficient, sustainable model, the US car–makers needed to adjust investment and production plans to recognise the inevitable loss of market share.

The Big Hub model didn’t break in the mid 90s ...

In the mid 90s, the Big Hub carriers earned the strongest profit margins in industry history, and were generating economic returns well in excess of the cost of capital. They had strong competitive advantage in many markets, and were only vulnerable to Quasi–Network growth in a small subset of existing markets. In order to continue to earn strong returns for shareholders, the Big Hub carriers simply had to:

- Strictly focus on strength markets, avoid Southwest strength markets and carefully monitor these competitive issues and threats;

- Strictly focus on their core business customers;

- Keep capacity and costs in line with their core revenue base over the full business cycle; and

- Ensure all stakeholders were working together to maximise shareholder returns over the cycle.

... it was abandoned

The 2002 financial crisis did not result from flaws in the basic economics of operating Big Hubs. It resulted when the industry ignored or violated almost all of the economic logic that drove hubs for decade and had directly created the profit turnaround of 1993–95. Tens of billions of dollars of economic value were destroyed when the Big Hub carriers, beginning in 1996:

- Expanded while ignoring competitive advantage;

- Set prices while ignoring customer value and competition;

- Expanded capacity while ignoring supply and demand; and

- Managed shareholder returns while ignoring the business cycle.

Expansion into unsustainable markets

Although total network retrenchment to "strength" hub markets had dramatically improved profitability (especially at Northwest and Continental) in the early 90s, several carriers pursued major expansions into markets where Big Hub competitive advantage was nonexistent.

American reintroduced local West Coast operations and acquired TWA in pursuit of a more ubiquitous presence and an increased national market share, despite the extreme competitive vulnerability and very poor historic profitability of these markets. Delta, US Airways and United actually developed major operations in markets where they would have a clear competitive disadvantage versus Southwest (Oakland–Los Angeles, Baltimore–Orlando).

Destroying value for business customers

Even with tightly constrained capacity, the Big Hub carriers were not powerful oligopolists in a position to drive business fares up at whim. In 1995 Southwest operated 3–4% of domestic capacity, but was clearly in a position to quadruple this share within a decade. The loyalty of the core Big Hub business customers requires that the higher fares charged be clearly offset by the value of the superior schedule and other service benefits.

In the early dot–com years, customers grudgingly accepted fare increases, but when the walk–up fares reached a level 7 or 8 times leisure levels, the long–standing perception of value for money broke down. Smaller airlines or discount restrictions that were previously avoided are now actively pursued, and business demand is apparently now much more price elastic.

The steep fare increases also created a huge price umbrella, encouraging Southwest and other Quasi–Network new entrants to compete much more aggressively for business traffic in traditional important Big Hub long–haul connect markets, emphasising growth in Buffalo–Phoenix and Nashville–Los Angeles instead of non–hub markets like Buffalo- Indianapolis or Nashville–Baltimore. A critical issue is that this shift will permanently reduce the "natural" market potential of the Big Hub carriers to an even smaller share than the 1993 analysis suggested.

Ignoring supply and demand

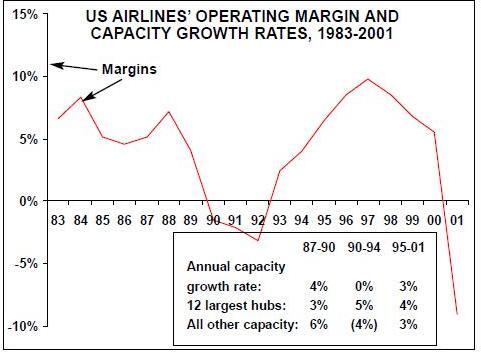

Although the mid–90s profit turnaround had been largely driven by five years of zero capacity growth, in 1996, the Big Hub carriers reversed course and grew ASMs 3% per year to2001. Capacity was added at relatively high marginal cost, but the revenue added was generally at very low incremental yields, either bottom- end leisure traffic, or passengers in competitively weak markets.

Big Hub pricing and yield management systems, highly effective under the constrained, near–equilibrium conditions of the mid–90s, broke down with excess capacity and increased Southwest competition. Growth depressed leisure prices, which in turn weakened the Big Hub distribution system as carriers turned to the Internet for more new ways to fill empty seats. Business fares were raised to cover the leisure shortfall and higher capacity costs, but quickly undermined by unrestricted $100–200 seats available with just a few clicks.

The core business revenue base was mature, and despite the behaviour of investment bankers in the late 90s was certainly not growing 3% a year. The inflation–adjusted revenue base over a full business cycle may have been shrinking, even before the risk on share loss to Southwest. The tendency of Americans to purchase unrestricted business fares was not growing faster than the economy, and past growth had been driven by declining fares.

Rational revenue maximising behaviour by the Big Hub carriers cut off any potential growth in business traffic in favour of lower volumes at higher yields. There was little reason to expect that productivity improvements could drive growth (simply holding unit costs in line would be a major challenge). Regional jets allowed certain carriers to capture share by providing more frequencies with the same ASMs, but did not provide a basis for profitably growing total industry ASMs.

Financial collapse due to badly justified growth plans seems to be one of the major themes in the history of civil aviation. Justifications for major fleet investment often emphasise aggregate traffic growth, rather than real revenue potential, or growth in core business demand. In the 90s, some carriers appeared to confuse dot–com yield increases with "market power" that would allow carriers to steadily drive prices upward. There were certainly pressures from Wall Street to demonstrate ongoing revenue growth. Whatever the reasoning, the aggregate result was the destruction of billions in shareholder value across the industry.

Ignoring long-term shareholder requirements

As a mature sector, airlines could not rationally expect earnings to continuously grow. However ,had they continued to pursue zero (average) capacity growth they could achieve strong average profitability over a full cycle. 1995–96 appears to have been roughly mid–cycle, and the Big Hub carriers earned healthy 9–10% margins. With zero average growth, the late 90s peak should have been extremely profitable, and carriers would have still been extremely healthy when the recession arrived. Shareholder value can be maximised as long as all stakeholders take a full–cycle view and no one group is capturing all the peak profits.

Instead, most Big Hub airlines told their stakeholders to focus on short–term results. Capacity growth and fleet expansion was heavily based on bubble–era growth. Management bonuses and stock options were based on quarterly/annual results despite the obvious presence of a cyclical boom. Insiders were benefiting from stock repurchases at dot–com peak prices while refusing to renegotiate union concessions made during the 92 crisis. Unions quickly adapted the same short–term view and won major increases that locked in dotcom level wages, while further polarising management and staff.

These higher capacity and wage costs caused Big Hub margins to fall in the late 90s, even though the economy was still strong. Desperate to prop up quarterly earnings, carriers responded with more and more dramatic increases in business fares.

Big Hub RASM increased 7% in 2000 despite having been flat the previous four years. Unfortunately CASM increased 9%. With the financial picture collapsing, the industry turned to consolidation, hoping that even greater concentration of "market power" could force enough cash from consumers to cover the aircraft and wage bills. The American- TWA acquisition and the proposed US Airways- United merger would have locked in most of the dot–com overcapacity and employee costs, while adding billions in new financial obligations.

Meanwhile Southwest took the opposite approach

By contrast, Southwest during this period stayed strictly within the economics of its Quasi–Network model. Its route expansion remained limited to markets where it had clear competitive advantage. Despite the boom and bust conditions of the late 90s, its capacity and market planning remained based on long–term, full–cycle criteria. And most importantly, all major stakeholders at Southwest were working together to maximise long–term (not quarterly) shareholder returns.

Although the success of Southwest is most often linked to its customer and employee friendly culture, the enormous economic value created over the last thirty years is more properly attributed to this strategic rigour and discipline, and its success in aligning the interests of all stakeholders.

Every aspect of Southwest’s operations and marketing (including its noteworthy culture) is clearly linked to the economics of the Quasi- Network model, and the competitive advantages and weakness of that model versus the Big Hub model.

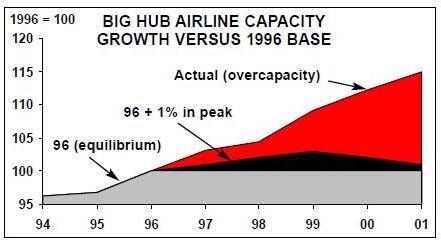

Big-Hub overcapacity was 10-15% before September 11

Industry overcapacity can only be estimated with respect to a point where supply and demand were roughly in equilibrium. In 95–96, all carriers (except TW) were earning strong profits, and the restructuring of weak hubs (Raleigh–Durham- Nashville) and weak balance sheets (Continental- Northwest–America West) was largely complete.

If 1996 is used as a base year, and zero (average) ASM growth would have maximised returns for the Big Hub sector as a whole, then there was 15% excess capacity in the industry prior to September 11. If 1% average growth from a 96 base was optimal then overcapacity was closer to 10%. If 95 conditions better reflect equilibrium then overcapacity was closer to 20%.

The graph also illustrates a case where carriers exploit the cyclical peak by delaying routine retirements of very old, fully depreciated aircraft, and then accelerating them as the downturn begins, capturing marginal traffic without increasing average capacity over the cycle. In either case it is clear that the overcapacity problem accelerated rapidly after 1999, when the downturn in the business cycle was clearly evident.

The overcapacity crisis obviously worsened when demand collapsed after September 11 but it is difficult to quantify this impact, or isolate incremental from pre–existing problems. To some extent revenue drops may reflect pricing and business elasticity changes that predated September 11, and to some extent post- September 11 conditions may have amplified earlier changes.

As year–over–year Big Hub ASMs have dropped 5%, the hypothesis here is that the recent cuts may have covered post September 11 revenue declines, but may have had little or no impact on the pre–existing 15% overcapacity problem.

Overcapacity created huge cost/balance sheet burdens

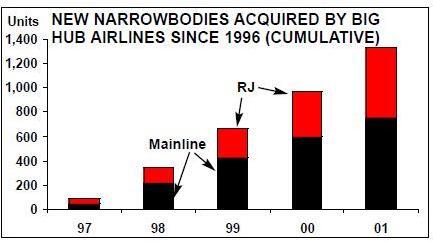

Big Hub airlines acquired 750 new Mainline narrowbodies plus 575 new Regional Jets since 96, while under a zero/low growth strategy they would have only acquired a small fraction of this number. Only 250 first generation jets were retired in this period and no carrier achieved major fleet simplification.

Perhaps as few as 500- 600 of these aircraft created economic value. This created much of the current Big Hub "cost problem" (especially when one considers the associated crew training and promotion costs) and the balance sheet burden limited financial flexibility after September 11.

What will it take to restore sustainable Big Hub profitability?

Those who view the Big Hub airlines as being as obsolete as the dodo are overlooking both the strong economics underlying the sector, and the fact that no alternative model has emerged that can serve most airline markets at lower cost.

However, the Big Hub sector is clearly facing a greater restructuring challenge than it faced ten years ago, but there is little visible evidence of proposals or concrete actions that might actually drive a turnaround.

Structural reforms would need to include major industry–wide cuts in business fares to levels that restore business traveller perceptions of value and large, across–the board capacity cuts, and zero future growth, aligned with these lower, but more realistic revenue expectations. If the Big Hub airlines are to survive in a cyclical, no–growth world over time, they will eventually need a basic realignment of shareholder and stakeholder expectations and compensation that better reflects that economic reality.

Several obvious problems can be noted. As in the early stages of the 92 crisis there is some level of denial, and perhaps some manoeuvring, in the hope that the collapse of a weaker carrier, or some other external event, will shift some of the pain elsewhere. Restructuring that requires huge initial cutbacks but with few near–term offsetting benefits is always difficult to achieve. The brunt of these cuts would fall on groups who did not really create the crisis and have already carried most of the burden of the post–September 11 cutbacks.

While major reform would be in the interest of all of the Big Hub carriers, new pricing and capacity regimes would require industry–wide acceptance, there are major obstacles to any actual coordination of planning or action. Aside from workout discussions via the Stabilization Board or chapter 11, there is little than any one airline can unilaterally do to move the process forward. And many management groups still rely on the outdated planning, pricing, and financial approaches that contributed to the failed decisions of the late 90s.

It is difficult to believe that meaningful recovery is possible if today’s capacity and pricing remains in place, even if certain carriers achieve important labour concessions. One danger is establishing an airline version of the vicious circle that paralysed the US car–makers response to Japanese competition. With no way to impose industry–wide structural reforms, each set of stakeholders fought to protect its historical position, while short–term management decisions continued to make the overcapacity and competitive problems even worse.

As with the automakers, slower reform means that the share of the domestic market the Big Hub airlines can profitably serve will continue to shrink.