Accidental nationalisation of

the North Atlantic

September 2020

The North Atlantic was the largest and most mature long-haul air transport market in the world, until March 2020. Since then it has in effect been shut down, operating at around 20% of 2019 capacity, which could profoundly alter the competitive landscape and regulatory framework.

The re-opening date is simply unknown, but it is now clear that a V-shaped recovery pattern is highly unlikely. The CEOs of various airlines have been pushing back on the year when 2019 traffic volumes will be recaptured: 2023 or 2024 appears to be the consensus at the moment. And even if traffic does get back to the 2019 level by 2023/24, it will be 15-20% below that expected and planned for in the pre-Covid world.

Post-Covid, when an effective vaccine is available or when travellers have adjusted to the risks of the disease, the transatlantic airline industry could resemble the pre-deregulation world — dominated by a few large airlines, owned or controlled by their governments, subsidised by their states, with limited real competition.

This outlook is partly the culmination of a trend that long predates Covid-19 (see, for example Aviation Strategy, November 2017). From 2009, the North Atlantic market has become increasingly consolidated and divided up among three multinational groups: the antitrust immunised joint ventures of Air-France-KLM with Delta (having taken over Northwest); the Lufthansa Group with United (having taken over Continental) plus Air Canada; British Airways, Iberia and Aer Lingus with American (having taken over USAirways). On the North Atlantic these groups, under the alliance brands of SkyTeam, Star and oneworld, became virtually merged entities, with the US and European partners making joint decisions on fares, schedules and capacity, sharing revenues and costs on a “metal-neutral” basis so that in theory there was no difference as to whose aircraft were operated, and producing their own consolidated (and confidential) financial accounts for the sector.

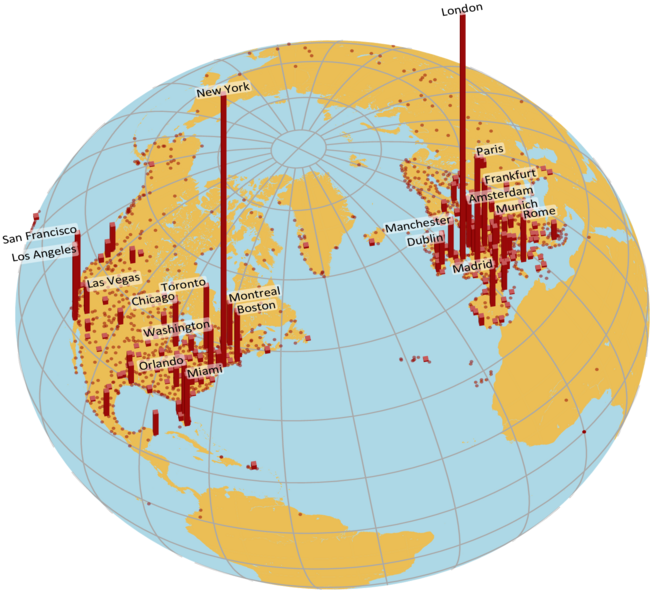

By the end of 2018 the three airline combinations had gained control of roughly 68% of the capacity on services between North America and Europe/Middle East (see chart), and their hub-to-hub routes across the Atlantic were in many cases completely monopolised. What once might have been seen as illegal collusion was protected through the antitrust immunity provisions of the joint ventures.

All of the network carriers appeared commercially robust in 2019, but that robustness proved to be an illusion once Covid-19 struck. Collectively the six network carriers have absorbed some $45bn in state aid in grants and loans, and another round of state funding of a similar amount is likely over the next 12 months, as Air France and Lufthansa have strongly hinted at the need for more funding, plus aid under the US CARES Act will probably be extended in October. For comparison, the combined stockmarket value of the six carriers as at the end of September 2020 was $44bn.

The consolidation process on the Atlantic was predicated on an open skies regulatory regime — which would allow, hopefully, new entrants onto the North Atlantic, injecting competition into the market. Covid-19 has largely finished off that competition.

Long-haul low cost capacity, in various forms, had peaked at about 12% of the North Atlantic total. But Norwegian’s operating model was being severely stressed before Covid-19, and survival prospects for the carrier, despite its own dose of state aid, look dim unless it too is nationalised. In which case it will join the myriad small European flag-carriers now fully supported by their states — Alitalia, SAS, TAP, etc. — which in the pre-Covid era had about 13% of the capacity on the Atlantic. The innovative Icelandic low cost hub operation has collapsed and the charter-type carriers like Thomas Cook either went out of business even before Covid-19 or have been left in limbo (Air Transat which was due to be merged into Air Canada).

It is somewhat ironic that the super-connectors — Emirates, Etihad and Qatar Airways — provoked such outrage in the US over state subsidies when they started to become a threat on the Atlantic, with about 9% of capacity. Their Middle East passenger hubs have been devastated by the pandemic, and recovery will be painfully slow. Funnelling huge volumes of passengers to/from 200-plus countries through a few terminals no longer appears to be an attractive prospect.

So after decades of extricating themselves from their national carriers, governments now find themselves as significant shareholders — 20% at Lufthansa, 28% at Air France/KLM — again supporting their major airlines. Under the CARES Act, which allocated some $50bn to US passenger airlines, the government will have the right to participate in “the gains of the eligible business or its security holders through the use of such instruments as warrants, stock options, common or preferred stock, or other appropriate equity instruments” — in other words, partial nationalisation. On the Atlantic, this means that effective government ownership and control of capacity may well be close to total when the industry emerges from Covid-19.

Governments’ new role

What role will governments play in this new world? Some of the conditions off the state aid reflect social aims — in Europe, the acceleration of carbon emission targets and the shifting short-haul passengers from air to rail while in the US the priority is the protection of jobs through no-furlough conditions — but the governments’ stated aim is to facilitate rapid turnaround strategies so their subsidised airlines can repay their loans or convert them into commercial debt. The terms of the loans incentivise this, for example Lufthansa’s interest rate on some of its state loans escalates from 4% pa to 9.5% pa in 2027. The Dutch government demanded a detailed recovery plan from KLM, which has now been delivered, as a condition of its state aid.

However, the challenges of restoring long-haul services to anything like pre-Covid operations are such that governments may find themselves enmeshed for the long term, in which case It is not difficult to envisage long-haul international airlines once again assuming the role of national champions or chosen instruments. Aeropolitics necessarily reflect global trends in politics, and the political and economic zeitgeist has changed profoundly over the past five years — from a consensual belief in the benefits of globalisation and free competition to diverse nationalistic agendas, protecting and promoting narrower interests.

Alliance conflicts of interest

One issue that may well arise concerns conflicts of interests within alliances. The North Atlantic joint ventures may not be as solid as they appeared to be in the pre-Covid era; just as military alliances re-align under the threat of war, so do commercial alliances under the stress of a lengthy recession or depression.

In the oneworld joint venture the two main participants have been diametrically opposed in their attitude to state aid; whereas American, has taken the maximum available, $10.6bn to date, IAG has minimised its exposure to what it sees as potential state interference, BA taking just £300m under a general industry support scheme, while Iberia and Vueling have received €1bn in total of Spanish state funding. IAG is the strongest of the European carriers in terms of liquidity, having raised €2.7bn through a rights issue (though nearly €700m of that came from Qatar Airways, which has been hugely subsidised by its state). American is the weakest of the Big Four US carriers and is regarded as being the most likely candidate for Chapter 11. IAG had the strongest position on the North Atlantic in terms of overall capacity, twice that of Air France, and was dominant in the point-to-point markets (essentially London-New York) and in the premium travel market. American has been relatively weak in the northeast US but in July signed a strategic alliance with JetBlue, with JetBlue providing a domestic feed operation to American’s transatlantic flights. It will be intriguing to see how this tripartite arrangement plays out when JetBlue starts up its own transatlantic A321 LR service, still scheduled for 2021.

In the Star joint venture the Lufthansa Group has been Europe’s most avid recipient of state aid — over €10bn — while United has focused on raising funds through monetising its FFP for $6.8bn, and has received just $5.0bn from the US government. Lufthansa’s problem is that it has a low proportion of transatlantic and other long-haul point-to-point traffic at its Frankfurt hub and has relied on its hubbing expertise to collect feed traffic. Downsizing a hub operation, as Lufthansa is planning, is a complex exercise as culling seemingly unprofitable short-haul routes may damage the viability of certain long-haul routes. Rationalising the hub network by consolidating long-haul traffic flows at Frankfurt and downgrading Vienna or Zurich is fraught with political problems. The state aid that the Lufthansa Group has received has come from Austria, Switzerland and Belgium as well as Germany, and those countries understandably want to protect air transport connectivity at their capitals, as do the various Länder within Germany.

In the SkyTeam joint venture Air France/KLM has received €10.4bn in state aid, two thirds from France and one third from the Netherlands, while Delta (which incidentally owns 9% of Air France/KLM) has taken $5.4bn in US government funding. The problem is that the pandemic has exacerbated existing tensions between Air France and KLM. Put crudely the Dutch resent the fact they have been the profit generator within the group while Air France is perceived to have made too many concessions to its unions. Despite assurances from the two governments that all is well between the two airlines, investors will have to be persuaded that the Air France/KLM Group is operating as a coherent entity before providing the funds necessary to replace the state loans (some of which rise to Eurolibor plus 7.75% in year six).

Indeed, relations between Air France and Delta seem to be closer than those between Air France and KLM. Paris represents the second most important O&D point after London. Air France’s new management might be considering whether, if the short-haul network can be rationalised, a downsized transatlantic operation, with a higher proportion of local traffic, emulating IAG’s Heathrow model, might be the way forward. Where this would leave KLM’s Amsterdam hub operation is unclear.

Collapse of premium business

The North Atlantic market has been heavily reliant on of premium travel for its profitability, but that sector has collapsed. At some point business travel will recover to pre-Covid levels but it is not going to be soon. The use of semi-efficient video technology — Zoom, etc. — is now universal; embattled corporations will continue to cut travel budgets; corporations have realised that they can use reduced business travel to meet their carbon reduction obligations; and super-elite passengers are much more likely to choose private jets.

This is particularly bad news for the transatlantic joint-ventures where premium passengers have accounted for 30-40% of their revenues. In the post-Covid world a 787 configured with 60 First/Business seats out of a total of 214 will still probably make sense on the key London-New York route, but on the thinner routes and hub-bypassing routes, smaller gauge equipment may well be the optimal solution — one that is being proposed by JetBlue with the launch of its A321 service featuring its MINT premium product.

It is not just premium volumes that have collapsed, premium class fares are down 70% year on year compared to a decline of around 30% for economy class, according to IATA. Pre-Covid the ratio of premium to economy fares was about 5:1 as a global average, higher on the main transatlantic routes. That type of ratio will not be achieved in the foreseeable future because to fill premium cabins premium fares will have to be moderated. Premium leisure is being promoted by some carriers, but this looks to be little more than a palliative strategy.

In short, for the revenue part of the profitability equation — average RASM to get close to balancing the cost part — average CASM — economy class fares will have to be raised. In turn, a rise in economy fares would threaten to choke off a substantial recovery in traffic volumes.

Fragility of feed networks

Unlike US domestic hubs, European hubs are designed to feed traffic from short-haul to intercontinental long-haul. This exposes their short-haul operations to direct and indirect competition from the LCCs. Hubs with low proportions of local long-haul traffic, like Frankfurt or Amsterdam, are more vulnerable than those, like Heathrow and to a lesser extent Paris, that have strong local long-haul traffic demand.

It is perhaps surprising that in the intra-European market pre-Covid, ie 12 months ago, the big three network carriers (including their subsidiaries) accounted for nearly 40% of seat capacity. Add in the smaller flag-carriers — Alitalia, SAS, TAP etc — and over 50% of intra-European capacity market is state subsidised and facing a fundamental restructuring, partly dictated by the conditions of state aid. The network carriers are being forced into addressing the reality of the economics of feed to their global hubs, abandoning unprofitable routes and airport bases. Non-hub flying is being rationalised nearly out of existence in some cases.

About 30% of the intra-European market is operated efficiently by the three well-capitalised and liquid LCCs — Ryanair, easyJet and Wizz Air — though each is differently positioned to deal with the post-Covid world. Wizz Air has made it clear that it intends to expand strongly when it is allowed to (Aviation Strategy, May 2020). Ryanair is on the point of making a classic recession-priced mega-order for 100-plus MAXes. They are going to encroach further onto the routes that the network carriers rely on for feed.

Streamlining of short-haul operations at Air France was overdue pre-Covid, and actions like phasing out the domestic subsidiary Hop! and moving to an A220 fleet should be beneficial for the airline’s finances, Lufthansa has perennially tried to defend unprofitable non-hub short haul services as a marketing defence for its hub feed. Pre-Covid it had been in the process of trying to develop Eurowings as a low-cost point-to-point solution, but has since cut back its plans.

Reducing short-haul services into hubs could undermine the viability of some long-haul services, and these in turn may have to culled. If yields are depressed further on short-haul as the result of increased presence of LCCs, the only option may be to increase fares on the long-haul services — reinforcing the premium travel reduction effect described above.

For the moment the network carriers are able to retain their precious slots at their main hubs, as the European authorities have suspended the 80/20 use-or-lose rule, but there is no guarantee that this waiver will be renewed for summer 2021. If not, excess capacity at these hubs may be seized by new entrants, probably LCCs, intensifying the competitive pressures on the network carriers and the joint ventures.

Network speculation

-

Nothing is clear in the post-Covid world, other than the fact that the key, previously highly lucrative, North Atlantic market faces a major medium-term disruption.

-

Governments, having been obliged to subsidise their network carriers, are going to find it more difficult to extricate themselves as quickly as is officially expected. By accident long-haul carriers may again become national instruments.

-

In Europe there will be a stark division between (mostly) unsubsidised IAG and the state-funded Air France and Lufthansa groups.

- The continental European hubs will have to been further rationalised and costs further reduced to protect streamlined feed operations to competitive attacks from the LCCs.

-

National interests and commercial pressures will increase tensions within the alliance joint ventures. To speculate wildly: if the continental European hubs are downsized permanently, would either of the other two relatively strong US partners consider attempting to displace the weaker American at Heathrow?

-

Structural changes in premium travel will probably push up economy fares which will slow the recovery in overall traffic volumes. Relying on premium class passengers to “cross-subsidise” discounted fares in the economy cabins will no longer be a viable tactic.

-

New opportunities will open up the North Atlantic for carriers with lower costs and the right equipment — JetBlue is well positioned — but as yet none of the European LCCs looks remotely willing to take advantage of a classic combination of depressed resource costs (aircraft, flying personnel, slots) and greatly weakened incumbents.