WestJet: LCC to “high-value

global network airline”

September 2018

Canada’s WestJet is in the midst of an ambitious transformation from an upmarket LCC into a full-service airline that caters for every kind of travel need. This involves scaling up the new ULCC unit Swoop, launching 787 operations in January, building a long-haul network to Asia and Europe, developing a dedicated premium cabin product, and capturing a greater share of premium travellers. WestJet also needs to secure a contract with its unionised pilots and keep unit costs in check.

The strategic shift, unveiled in February 2017, seemed risky from the start, but WestJet’s track record of profitability and executing multiple strategic projects since 2010 won over the initial critics.

But this year has seen alarming developments. WestJet’s pilots threatened industrial action in the spring, which came close to preventing Swoop’s launch, damaged the WestJet brand and led the airline to report its first quarterly losses in 13 years for Q2.

WestJet was fortunate to avert the strike threat in late May when it agreed with ALPA on the settlement process, which includes binding arbitration, if necessary. But the contract could lead to significant labour cost inflation.

WestJet attributed its Q2 losses to a 31% surge in fuel prices, as well as domestic yield pressures resulting from overcapacity. The airline is especially concerned about the “doubling of the network of a ULCC competitor” this past summer (Flair Airlines, more on that below).

One more thing to add to WestJet’s challenges: several management changes in the past several months, including a new CEO. Former CEO Gregg Saretsky resigned in March amid the labour strife, and new CEO Ed Sims only joined the company last year.

It all adds up to a challenging financial outlook. In early August JP Morgan projected that WestJet’s EBIT margins would dip to historical lows of 3.3% and 5.5% in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

JP Morgan noted WestJet’s “troubling” cost trajectory. While 2019 unit costs cannot yet be accurately projected because there are so many moving parts, in the best estimate WestJet’s 2019 ex-fuel CASM (10.34C¢) will be only 4% below Air Canada’s 10.80C¢ — quite shocking as WestJet is still an LCC and Air Canada is a full service airline. Four years ago WestJet had a nearly 20% cost advantage over Air Canada (on a non-stage length adjusted basis).

This adds to the pressure to grow Swoop rapidly and obtain ULCC-level CASM for the unit. Yet WestJet’s management is also under pressure to stem the 2018-2019 margin degradation.

WestJet has announced a six-point reduction in its planned Q4 growth rate, which results in 2018 ASM growth declining from 6.5-8.5% to 5.5-6.5%. The management is also “re-evaluating the phasing and implementation” of some of the strategic projects, which could be announced at the investor day in December.

Why the strategic shift?

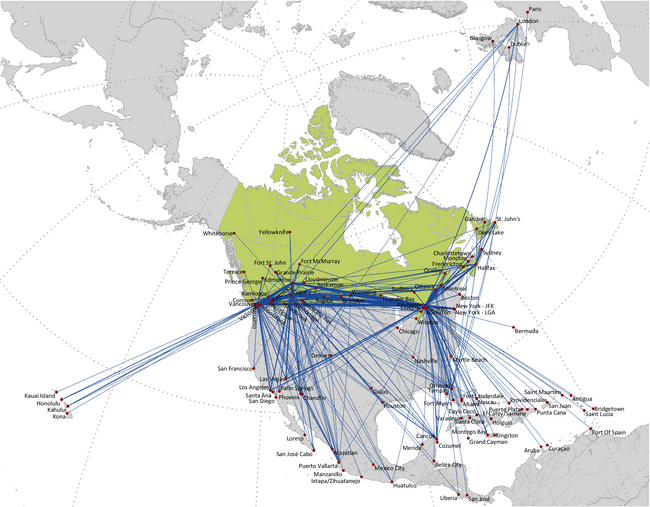

The main reason why WestJet is diversifying away from its tried-and-tested, profitable LCC model is that it needs new growth areas. It has 37% of domestic ASMs (a virtual duopoly with Air Canada in the domestic market), 21% of ASMs in the Canada-US market and a strong position in the Canadian winter sun market to Florida/Mexico/the Caribbean.

But with Canada’s 36m population (2016), WestJet does not have the opportunities that US LCCs enjoy in being able to tap the huge US market for domestic and near-international expansion.

WestJet knew already in 2011 that it would benefit from diversification, both geographically and with its business model. It has moved aggressively to capture business traffic in Canada, launched regional subsidiary WestJet Encore (2013), entered the transatlantic market (with 737s in 2014 and 767-300ERs in 2016) and tested the Canada-Hawaii market.

At the same time, Air Canada too has increasingly diversified into WestJet’s territory; most notably, it has set up its own low-cost unit Rouge.

There is a strong defensive element to WestJet’s latest diversification moves. The competitive landscape in Canada is changing, with both existing operators and new entrants increasingly posing a potential threat to WestJet’s market position.

Air Canada is growing faster domestically. Rouge has had its earlier 50-aircraft cap removed. LCC Air Transat is planning European expansion, while Sunwing is stepping up growth on the winter sun routes.

But upstart ULCCs pose the biggest threat to WestJet’s domestic market share. Despite being a tough market for new airline entrants, Canada has suddenly become a hotbed of ULCC start-up activity. WestJet’s biggest priority this year was to get Swoop launched and scaled up before new ULCC competitors could get a foothold.

WestJet has been lucky on that front. Two of the companies that originally looked the strongest — Canada Jetlines and Enerjet — have both experienced fundraising delays and are unlikely to start operations before 2019, at the earliest. That was despite the fact that in late 2016 the government exempted them from the earlier 25% foreign ownership cap (the Act that raised the cap to 49% finally became law in June 2018).

Instead, former charter operator Flair Airlines, which now markets itself as a ULCC, has become WestJet’s biggest immediate concern. Flair began scheduled flights after absorbing ULCC hopeful New Leaf in June 2017, and this summer it doubled its domestic operations to cover 10 cities. The airline will make a big transborder push this winter, with service to six US destinations from December. It plans to start transitioning from 737-400s to 737-800s in early 2019.

Geographical diversification also helps protect WestJet from adverse economic and exchange rate developments. As a non-US airline, its dollar-denominated costs rise when the Canadian dollar weakens.

WestJet has been profitable through its 22-year history, except for a small operating loss in 2004. It has proven that it can be successful in the competitive transatlantic market where it does not have much of a cost advantage. It continues to enjoy a strong balance sheet, ample cash reserves and investment grade credit ratings. Cash represented 28% of LTM revenues in June. Adjusted debt-to-equity ratio was 1.42 and adjusted net debt-to-EBITDAR ratio was 2.18.

The management stated in August that it still intended to achieve the 2020 financial targets laid out in its December 2017 plan, which include achieving ROIC of 13-16%, operating margin of 10-12% and adjusted net debt-to EBITDAR of 1.2. But ROIC was last in that range in 2015 and fell to 7.7% in the 12 months ended June 30.

WestJet’s results in 2018 are so seriously off-track that attaining the 2020 targets seems challenging — at least without a significant scaling down of the strategic initiatives. The problem there is that the key initiatives seem essential for achieving the cost and revenue targets. WestJet would be especially loath to reduce Swoop’s growth rate now that there is an aggressive ULCC competitor in the market.

Perhaps WestJet will find a way to slow new aircraft deliveries without too much adverse impact on the strategic initiatives. Currently its capital plans show a peak in 2019 at around C$1bn, which includes C$820m aircraft capex.

Plans for ULCC Swoop

Swoop took to the air in June with two 737-800s, initially focusing on a five-point domestic network (Abbotsford, Edmonton, Halifax, Hamilton and Winnipeg). It has since received regulatory approvals to fly to the US, Mexico and some Caribbean countries and will be adding its first seven Canada-US routes in October — ahead of Flair’s transborder entry. The initial US destinations are Las Vegas, Phoenix/Mesa, Orlando, Tampa Bay and Ft. Lauderdale.

In early September Swoop operated four 737-800s. The plan is to build the fleet to six units by December and 10 by the autumn of 2019. All of the aircraft come from WestJet and they have been converted to a 189-seat higher-density configuration.

The business model is typical ULCC: fully unbundled fares, high ancillary revenues, high utilisation, high labour efficiency, direct-only distribution and simplicity. Costs are targeted to be 30-40% lower than WestJet’s.

Swoop’s AOC, brand, employees, headquarters, airport operations and website are all separate from WestJet. The unit is led by a WestJet EVP.

The target market is price-sensitive travellers, as opposed to WestJet’s “core leisure and premium guests”. The idea is to stimulate travel (about 50% of the target market).

A further aim is to capture what WestJet calls “cross-border leakage” (25% of Swoop’s target market). Some 5m Canadians annually cross the border to US airports such as Bellingham and Buffalo to catch cheap flights operated by US ULCCs such as Spirit and Allegiant. From Abbotsford and Hamilton on the Canadian side, Swoop can match the US ULCCs’ fares to popular leisure destinations such as Las Vegas and Florida, especially since Abbotsford and Hamilton are lower-cost, “highly collaborative” airports.

The main tool for preventing Swoop from cannibalising yields at WestJet is to keep the two networks separate. Swoop operates point-to-point services and does not feed to WestJet’s long-haul network.

WestJet originally outlined a 6C¢ ex-fuel CASM target for Swoop, which according to JP Morgan was about 0.8¢ higher than the stage-length-adjusted US ULCC average to account for structurally higher costs in Canada (especially airport and navigation fees). The 6¢ target will only be realised when Swoop gets economies of scale with a 10-strong fleet.

Apparently the proposed ALPA wage settlement is not that different from WestJet’s original assumptions, so the 6¢ target still stands. However, the mere fact that Swoop’s pilots are unionised (and all come from WestJet) could mean less operational flexibility and limit the unit’s potential to drive down costs.

Only a few months ago ALPA was alleging that WestJet broke their contract by introducing Swoop. It could take a while to repair labour relations.

Swoop’s early results have surpassed expectations, though, with load factors consistently exceeding 95% and ancillary revenue per passenger approaching double that of the mainline operations. WestJet executives said recently that they are “actively looking” to accelerate Swoop’s growth from the 6-10 aircraft committed so far.

But Swoop will always be a small airline. Canada is a small market. Earlier this year WestJet’s former CEO said that he envisaged Swoop “one day” operating a fleet of 30-40 737-800s.

The up-market push

As a high-quality LCC with an award-winning product, a strong brand and a great domestic market position, WestJet has always attracted business and premium traffic. It has courted it with Plus premium economy seating with extra legroom (introduced in 2012), better schedules, improvements to the FFP and suchlike.

But, in the words of one analyst, WestJet still “punches below its weight with higher-value travellers in Canada”. That is partly because of gaps in its product offering, such as not having a dedicated premium cabin product (like, for example, JetBlue’s Mint), Also, Plus is not as attractive as competitors’ comparable offerings.

The 787 and the 737 MAX have provided an opportunity to rectify that. The 787 fleet will feature WestJet’s first-ever, albeit “appropriately sized” dedicated premium cabin, which among other things will include lie-flat seats.

If successfully executed, the 787 premium offering could potentially disrupt the segment as much as JetBlue’s Mint did in the US. But it could also be an earnings headwind. Long-haul international is a tough market, full of global carriers with more spending power and experience in perfecting their premium cabins. Much will also depend on correct route selection and revenue management.

It is even more important for WestJet to capture more premium traffic in the domestic market. It will help offset Swoop’s lower yields. WestJet hopes that an enhanced Plus offering on the MAX 8s, together with the upgrades planned to the 737-800’s, will do the trick.

WestJet is targeting C$300m of incremental domestic premium traveller revenue — by far the biggest contributor to the overall revenue opportunity of up to C$500m it has identified through 2022.

In addition to global growth, the other revenue contributors include a new transborder JV with Delta, new fare and ancillary products and enhanced revenue management tools.

WestJet continues to cater for different customer segments with fare bundles (Econo, Flex, Plus Lowest, Plus Flexible). Oddly though, and as a sign of how complicated the business model is becoming, WestJet is also introducing Basic Economy fares across its domestic and transborder networks (that fare type is the US legacies’ primary weapon against ULCCs).

Global expansion with the 787

WestJet has four-plus years of experience operating on the transatlantic. In 2014 it introduced seasonal Toronto-Newfoundland-Dublin services with 737s, adding a second route, Toronto-Halifax-Glasgow, the following year. In 2016 it began operating nonstop flights to London Gatwick from six Canadian cities with its owned 767-300ERs.

WestJet is now about to embark on a significant new phase of its international expansion as it receives its first 787s in early 2019. It has firm orders for 10, scheduled for delivery in 2019-2021, plus 10 options (available in 2020-2024).

But WestJet has currently no plans to start retiring the 767-300ERs, which it considers add useful cargo capacity and are ideally suited for flights of 6-8 hours’ duration.

The airline unveiled the 787’s livery, logo and cabin interiors in Q2. In line with the strategy to become a full service airline, the 787s will be operated in three-class configuration. Back in the summer, WestJet talked about launching sales in Q4 and having the first aircraft in service by the end of January.

As of September 18, WestJet had not yet announced any 787 destinations. The type’s range from Calgary, Toronto and Vancouver will literally open up the world, but more destinations in Europe, some Asian routes (especially China) and possibly upgauging the key London routes to the 787 are thought to be early priorities.

WestJet will benefit from Canada’s great collection of traffic rights around the world, which Air Canada too only began seriously taking advantage of fairly recently.

But WestJet can expect more and bigger competitive clashes. Asia happens to be a key growth market for Air Canada. It was indicative that Air Canada and Air China recently announced plans for an enhanced JV.

WestJet is in a much stronger position than the typical point-to-point LCC in that its extensive domestic and North American networks can provide significant feed to long-haul international services.

To supplement the feed provided by its own 737 operations and by wholly-owned regional unit Encore’s 45-strong Q400 fleet, in June WestJet launched its first contracted flying under a capacity purchase agreement (CPA). The initial “WestJet Link” contract, with Pacific Coast Airlines in Calgary, is very modest, but the model can be replicated across Canada. PCA’s 34-seat Saab 340Bs are painted in WestJet colours and have six Plus seats available.

Airline partnerships will play a major role in making the global strategy successful. WestJet is an old hand at those and has codeshares in place with numerous airlines. Two things mentioned in recent months are talks with Air France-KLM to deepen transatlantic cooperation and exploring new or deeper relationships on the transpacific.

One particularly significant development is the signing of a Delta/WestJet transborder JV in July. The deal covers 30-plus cities or nearly all of the US-Canada demand. It envisages expanded codesharing, FFP and reciprocal elite benefits, joint growth across the transborder network, co-location at key hubs and cooperation in cargo and corporate contracts. The airlines expect to obtain the regulatory approvals in the first half of 2019.

This deal is important because it could materially help WestJet secure feed from the US to its future 787 services and aid its quest to become a full-service, global airline. It could be the first and only immunised JV in the US-Canada market, though it has to be only a matter of time before Air Canada and United revive their earlier JV plans.

Uncertain cost outlook

In May, to avert industrial action and get the pilot contract settlement process agreed, WestJet made a major concession to ALPA: it agreed that Swoop pilots will be unionised and covered by the same contract as the mainline pilots.

In other words, Swoop pilots will have the same pay rates as WestJet pilots, who are now seeking wage parity with Air Canada pilots. However, it looks like pilots transferring from WestJet to Swoop will lose their seniority, enabling Swoop to obtain some savings through a young workforce. It is not yet known if there will be productivity concessions to facilitate more flexible work rules at the ULCC.

With the negotiations continuing, it is unclear how swiftly and amicably the first ALPA contract can be put in place and how much it will inflate WestJet’s labour costs. Pressures on that front will continue also because in July WestJet’s and Swoop’s cabin crew members voted to join a union.

Nevertheless, WestJet is committed to “staying ahead of our cost inflation” and even widening its competitive cost advantage with Air Canada. The management calls 2018 a “year of transition” that has included significant start-up expenses and expensive product launches. Thanks to the 737 densification and other projects, WestJet is on schedule to meet its “cost transformation program” goal of C$200m annual savings by the end of 2020.

The transition to the 737 MAXs over time and the growth of the 787 fleet should certainly help WestJet keep its unit costs in check, but it remains to be seen if the multiple other cost challenges can be averted and if the complex revenue strategies will pay off.

| Current | Future deliveries | Fleet | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fleet† | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022-23 | 2024-27 | Total | 2027 | |

| 737-600 | 13 | 13 | |||||||

| 737-700 | 54 | 54 | |||||||

| 737-800 | 48 | 48 | |||||||

| 737MAX 7 | 1 | 2 | 19 | 22 | 22 | ||||

| 737MAX 8 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 21 | ||

| 737MAX 9 | 10 | 2 | 12 | 12 | |||||

| 767-300ERW | 4 | 4 | |||||||

| 787-9 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 10 | ||||

| Q400 | 47 | 47 | |||||||

| Maximum‡ fleet | 173 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 14 | 21 | 58 | 231 |

| Lease expiries | -6 | -5 | -11 | -12 | -7 | -41 | -41 | ||

| Minimum§ fleet | 173 | 4 | 3 | -2 | -4 | 2 | 14 | 17 | 190 |

Notes: There are options to purchase another 21 MAX aircraft and ten 787s for 2020-2026 delivery. The MAX 7 and MAX 8 orders can be substituted for one another or, beginning in 2022, for the MAX 10. † At 30 June. ‡ all leases renewed § all leases allowed to expire

Source: WestJet

Note: 2018 and 2019 forecasts by J.P. Morgan (August 2, 2018)

Source: Company reports

Notes: Data not adjusted for average stage length differences. 2018F = Mid-point of each airline's guidance; 2019F = Forecasts by J.P. Morgan.

Source: Company reports