Cathay Pacific: 2016 brings

intense pressure

Aug/Sep 2016

Cathay Pacific Airways experienced a brutal six months in the first half of 2016, with profits plunging 82% year-on-year thanks to fierce competition, weak demand in some markets and hefty losses from poor fuel hedging. Will those trends continue for Cathay through the rest of this year?

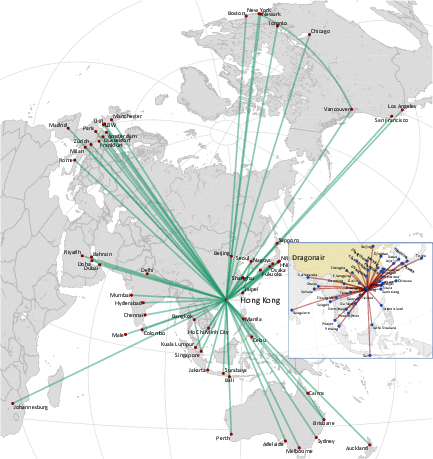

Hong Kong-based Cathay Pacific Airways operates to more than 170 passenger and cargo destinations in 40+countries, with the airline employing 23,000 (of which 16,600 are based in Hong Kong), and the Group a total of 33,800 worldwide.

Cathay had an excellent 2015, with group profit up 91% to HK$6bn (US$774m), but there were warning signs in the second-half of the year with premium demand not as strong as expected on some long-haul routes and the air cargo market becoming weaker.

The first half of calendar 2016, however, was worse than many analysts expected. Group revenue of HK$45.7bn (US$5.9bn) was a worrying 9.3% down on the January-June 2015 period and, of that, passenger revenue totalled HK$33.4bn (US$4.3bn) — down 7.8% year-on-year.

The group says that “the operating environment in the first half of 2016 was affected by economic fragility and intense competition. There was sustained pressure on revenues, reflecting suspension of fuel surcharges (from February), weak currencies in some markets, weak premium class demand, particularly on long-haul routes, and a higher proportion of passengers transiting through Hong Kong”.

In the first half of 2016 Cathay (and subsidiary Dragonair) carried 17.3m passengers (a rise of 2.7% year-on-year). Capacity increased 4.2% in the six-month period, but traffic growth lagged behind at 2.6%, leading to a 1.4 percentage point decrease in load factor, to 84.5% — which threatens to halt what had a been a continuous improvement in annual load factor over the last three years (see chart).

In the first half of 2016 passenger yields fell by 10.1% to HK¢54.3, which according to Cathay reflected “the suspension of fuel surcharges, strong competition and adverse currency movements”. Digging deeper into the numbers released by Cathay reveals that there was a significant reduction in premium corporate travel on all routes, but particularly on long-haul. Overall Cathay’s revenue from long-haul declined compared with January-June 2015, despite a 4.7% increase in long-haul capacity.

Group attributable net profit fell a massive 82.1% year-on-year, from HK$1,972m (US$254m) in H1 2015 to HK$353m (US$45.4m) in January-June 2016. Fuel is the largest cost component for the group (accounting for 29.1% of operating costs in the first half of 2016). After hedging fuel fell by HK$3,360m (or 20.2%) in H1 2016 — though Cathay is still hampered by losses on its fuel hedging contracts, which cost the group some HK$663m in the period. Cathay also lifted its fuel surcharge in February, and this remains suspended to date.

Though productivity has continued to improve and non-fuel costs fell by 0.5% per ATK in the first half, the group has responded to weaker revenue by carrying out a review of all non-fuel expenditure. Measures already taken include the freezing of new and replacement staff for all “non-operationally critical” functions, as well as cutbacks on non-essential discretionary expenditure.

Fleet renewal

In terms of the fleet, Cathay operates 124 passenger aircraft, comprising 53 777-300ERs, 42 A330-300s, 12 777-300s, five 777-200s, five A340-300s, four A350-900s and three 747-400s. They have an average age of less than nine years. Fleet renewal is continuing — the last 747-400s will go by the end of October this year, while one A340-300 will be retired in the second-half of the 2016 and the remaining four in 2017.

On order are 65 aircraft — 26 A350-1000s, 18 A350-900s and 21 777-9Xs. The first of an order for 22 A350-900XWBs was delivered in May, and four have been delivered so far this year, and with eight more due by the end of 2016 and the rest in 2017. The A350-1000s will arrive between 2018 and 2020.

The first aircraft have been used initially on routes within the Asia/Pacific region (including from Hong Kong to Manila, Taipei, Bangkok and Singapore), before being deployed on long-haul routes to Europe from September, including London and Düsseldorf.

Significantly, Cathay is not installing any first-class cabins on the A350-900 and -1000s, and is instead fitting out the aircraft with a larger number of premium economy seats (with three classes in total — business, premium economy and economy).

First class is being retained on 777-300ERs to “trunk routes” out of Hong Kong (to destinations such as London, New York and Los Angeles), and will be introduced onto the new 777-9Xs, which will arrive from 2021. Cathay Pacific is already the largest operator of the 777 in Asia.

The group’s cargo operation — 14 747-8Fs and 11 747-400Fs with a single 747-8F on order — has been hit hard by overcapacity and economic downturns in key markets globally. In the first half of 2016 Cathay’s cargo revenue fell a substantial 17.2%, to HK$9.4bn (US$1.2bn), and cargo load factor at the group was just 62.2% (and that was 1.9 percentage points lower compared with the first six months of 2015).

The Cathay Pacific Group also owns Hong Kong Dragon Airlines (100%) and AHK Air Hong Kong (60%). Hong Kong Dragon Airlines previously operated under the brand name Dragonair to regional Asian destinations with a fleet of 19 A330s, 15 A320s and eight A321s. However, in January the Group announced that Dragonair was to be rebranded as Cathay Dragon (though they will remain separate airlines), and aircraft began to adopt the new Cathay Dragon livery in April. Air Hong Kong is a cargo joint venture with DHL Express, and operates 10 A300-600Fs and three 747Fs.

The poor half-year results — and a previous warning by the company of the impending financial downturn — were met by a raft of downgrades by Goldman Sachs and other analysts. For example, in June Singaporean bank UOB Kay Hian said that “China Southern has added capacity to international routes by 26% in the year to date, and more passengers may choose to fly with the airline out of Guangzhou as congestion at Hong Kong continues”.

Hong Kong problems

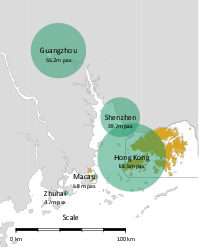

Cathay continues to battle against overcrowding at its hub, Hong Kong International Airport. Though only opened at Chek Lap Kok island in 1998 (replacing Kai Tak airport), it has grown to serve 68.5m passengers and 406,000 air traffic movements (ATMs) in 2015 — perilously close to its maximum capacity of 420,000 ATMs.

Cathay had been urging the construction of a third runway and terminal for many years, and this was finally approved by the Hong Kong Executive Council in April this year (at an estimated cost of HK$141.5bn — or US$18.2bn). Once it is finished, the new runway will allow capacity expansion to more than 100m passengers and 607,000 ATMs by 2030, but despite construction starting in August it will not be completed until 2024 at the very earliest (assuming no delays), as it is a complex project requiring reclamation of 650 hectares of land north of the existing airport island. Meanwhile, full capacity at the existing facilities will be reached well before then, either this year or 2017 at the latest.

The sluggishness (in Asian terms) of the Hong Kong authorities to make a decision hasn’t gone unnoticed by regional airport competitors, with most of them far advanced in expansion plans. Singapore Changi is building a fourth terminal to open in 2017 and a third runway (being converted from a military one) by 2020; Guangzhou Baiyun will build a second terminal (2018) and fourth runway (2020); and Shenzhen Bao'an will build a third runway by 2018 — and all of these developments will be completed well before the third runway is completed at Hong Kong, in 2024.

Increasing competition from Chinese airlines is a huge challenge to Cathay, particularly as many of them are piling on long-haul capacity, fuelled by new aircraft deliveries and by growth in international demand by the relatively affluent Chinese middle class. In particular capacity is being added onto routes into North America, which is having an adverse effect on premium yields for Cathay.

To make matters worse, many of the Chinese carriers are expanding international networks out of nearby airports in mainland China. For example, Shenzhen’s Bao’an airport is located just 38km from Hong Kong airport and didn’t have any scheduled, non-stop long-haul routes before 2016 — yet it now has three from three different airlines — to Sydney (operated by China Southern), Frankfurt (Air China) and Seattle (Xiamen Airlines), with at least three further new routes planned to open by the end of the year (including a service to Los Angeles).

The bigger threat comes from Guangzhou airport, some 135km from Hong Kong and which is the main hub for China Southern — with huge spokes of domestic flights drawing passengers onto its international flights.

In the face of this competition and despite an agonising wait for extra capacity at Hong Kong, Cathay’s strategy will continue to promote “Asia’s premier aviation hub”. However, even here the group is starting to face a growing challenge from the only LCC based at Hong Kong — HK Express, which was launched in 2004 by a local entrepreneur before HNA Group, the parent company of Hainan Airlines, bought a 45% stake in 2006. It evolved into an LCC in 2013, and today operates 14 A320s to more than 25 destinations throughout Asia — of which 14 are in direct competition with Cathay routes. HK Express also has 15 A320neos on order, and aims for a fleet of 30 aircraft by 2018.

2016 doldrums

Despite the good results in 2015, Cathay had already decided to scale back capacity growth in 2016 early on in the year, although perhaps this was more luck than judgment thanks to a labour dispute that forced the airline to refine its plans.

The Hong Kong Aircrew Officers Association, which represents 2,100 of the 2,900 pilots employed by Cathay, took part in a work-to-rule earlier this year in an attempt to change work rosters that it claimed were unfair, and this reportedly led Cathay to put on hold the launch of new routes from Hong Kong to Manchester and Boston. They will now start up sometime in 2017. However, in June Cathay did launch a route to Madrid, and in September a route was launched to London Gatwick, using new A350-900XWBs that will operate four times each week.

The Cathay Pacific Group is listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange, and as can be seen in the chart though the group’s share price has been volatile over the past few years, it has fallen substantially recently, from around HK$20 as at April 2015 to under HK$12 as at September this year.

The major shareholder remains the The Swire Group conglomerate, with a 45% share, while Air China has a 29.9% stake. Cathay itself still holds a 20% share of Air China, but the potential merger of the two airlines that was mooted just last year (see Aviation Strategy, May 2015) hasn’t happened, even though this would have provided Cathay with substantial amounts of mainland Chinese feed into its long-haul routes out of Hong Kong. Nevertheless, Cathay says it still wants to develop its relationship with Air China.

Cathay’s challenges will continue through 2016 and into 2017. In August John Slosar, chairman of Cathay Pacific, said that he expected the operating environment in the second half of the year to continue to be impacted by the same adverse factors as in the first half. He warned: “The overall business outlook therefore remains challenging — we expect passenger yield to remain under pressure”.

| as at 30 June | Deliveries | |||||||||

| Aircraft | Owned† | Operating lease | Total | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | >2021 | |

| Cathay | A330-300 | 36 | 6 | 42 | ||||||

| A340-300 | 5 | 5 | (1) | (4) | ||||||

| A350-900 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 11 | ||||||

| A350-1000 | 6 | 10 | 10 | |||||||

| 747-400 | 3 | 3 | (3) | |||||||

| 777-200 | 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 777-300 | 12 | 12 | ||||||||

| 777-300ER | 30 | 11 | 53 | 3 | 2 | |||||

| 777-9X | 21 | |||||||||

| Passenger aircraft | 103 | 18 | 121 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 10 | 21 | |

| 747-400F | 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 747-400BCF | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 747-400ERF | 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 747-8F | 13 | 13 | 1 | |||||||

| Freighters | 23 | 1 | 24 | 1 | ||||||

| Dragonair | A320-200 | 5 | 10 | 15 | ||||||

| A321-200 | 2 | 6 | 8 | |||||||

| A330-300 | 10 | 9 | 19 | |||||||

| 17 | 25 | 42 | ||||||||

† Includes finance leases

TRAFFIC DATA

Note: main map drawn using azimuthal equidistant projection centred on HKG. Great circle routes appear as straight lines.

Note: Area of circles directly related to number of airport terminal passengers 2015