Fastjet: The struggle to democratise African air travel

September 2013

Africa would appear to have huge potential for the growth of LCCs. It also presents formidable obstacles and complexities. Fastjet is objectively a small airline, with a current annual passenger volume of less than one million passengers, but it has achieved a high profile, and its short history illustrates both aspects of the African market.

Flights under the fastjet brand started up in Tanzania in November 2012 using three A319s, operating from Dar es Salaam to Kilimanjaro, Mbeya and Mwanza. Fastjet plc is the holding company for fastjet itself (which was developed from the former Fly540 operation in Tanzania), plus other Fly540 operations in Kenya, Ghana and Angola.

Starting with the potential, Africa has a great economic future ahead (and always will have, according to the sceptics):

- More than one billion people, of whom maybe one third can now be described as “middle class”

- Rapid economic growth (GDP in the 5-6% pa range)

- Huge Oil, Gas and natural resources

- $1.6 trillion consumer spend by 2020 (according to McKinsey)

- Infrastructure investment by governments and NGOs

- Restructuring of debt

- Hopefully, increasing political stability across the continent

Against this positive background, the aviation scene looks totally underdeveloped:

- Africa has 15% of the world population, 20% of the world land mass but less than 3% of world RPKs

- Propensity to fly: less than 0.1 seats per capita per annum in contrast to Europe’s 2.0 seats per capita per annum

- 10.85 accidents per million flight hours, compared to a world average of 2.00

- Long history of failed operators and wasteful flag-carriers

- Poor reliability, with endemic cancellations and delays

- Liberalisation, as promised by the Yamoussoukro Agreement, is still far off, and travel between all 48 countries of sub-Saharan Africa remains controlled by Bilateral Air Service Agreements.

Fastjet’s aim is to resolve this conundrum. Its mission statement is to implement the low-cost model across Africa, becoming the continent’s first low-cost, pan-African airline. Management is packed with LCC expertise: CEO Ed Winter (Go and easyJet), CCO Richard Bodin (easyJet) and CFO Angus Saunders (British Mediterranean and Avianova, a Russian LCC which was forced out of business). Parallels could be been drawn with India where domestic air traffic shot up from 14m passengers a year in the mid 2000s to about 70m now, following the arrival of LCCs like Indigo and SpiceJet.

The fastjet plan at its launch last year was for rapid growth in its fleet to 10 aircraft this year and 25-30 by 2015, as it applied the LCC experience of, mostly, easyJet to the African continent. But the current fleet remains at three, and the organisational structure of fastjet has been questioned. The airline is headquartered at London Gatwick where the top management work. There have been rumours of relocation — but to Dubai, rather than an African city. How, critics ask, can fastjet adapt the LCC model to Africa if it isn’t immersed in Africa?

However, fastjet can point to its marketing successes. At its most basic level this involves educating passengers about its “European” safety standards, demystifying the flying process (38% of its passengers have been first time flyers), through friendly videos, and establishing the brand.

It has tackled the African airline phenomenon of “Go Show”, whereby passengers don’t turn up at the airport until the very last minute to purchase their tickets, suspecting, correctly, that their desired flight will be delayed or just not happen. Fastjet’s on time performance from Dar es Salaam this year is put at 96% and cancellations at less than 0.1%, efficiency ratings unheard of in domestic African aviation. Consistent LCC pricing has also changed consumer behaviour; fastjet’s one-way prices average $70 (ex taxes) but are sold at around $20 for early booking while last minute tickets go up to $170. As in Europe, passengers quickly learn the LCC model. According to fastjet, its average advance booking/departure ratio has changed from 0.7 days when operations started at the end of 2012 to 15 days now.

Although internet usage is comparatively low in Africa, the website fastnet.com appears to be very well accepted in Tanzania, with over a million visits since its launch and a very respectable sale conversion rate of 8%. Mobile ownership is extraordinarily high in Africa (allegedly an average of two phones per capita) and has become a standard medium for making transactions and transferring money. About 25% of fastjet’s sales are via mobiles, the airline having entered into a partnership with Tigo, the global, but South America and Africa focused, telecoms provider, earlier this year. Through facebook and other social media, fastjet claims to be the fifth most popular brand in Tanzania and the most “liked” airline in sub Saharan Africa.

Fastjet’s logo is a fetching grey parrot, widespread throughout Africa, which is a very intelligent bird. It would undoubtedly applaud fastjet’s operating and marketing successes but might squawk loudly at the financial results.

When fastjet was generating publicity and seeking funding last year the idea was that it could quickly become a pan-African LCC (see Aviation Strategy, December 2012) through acquiring the existing AOCs of Fly540, the aviation arm of the Africa-orientated conglomerate Lonrho (London-Rhodesian, if you go back far enough). A former software company, Rubicon, was used as a cash shell to absorb the aviation assets of 540 (two aircraft and the licences for Tanzania, Kenya, Angola and Ghana) as well as its liabilities. In the new company, fastjet plc, Lonrho became a 50% shareholder while Sir Stelios Haji-Ioannou, easyJet’s founder and owner of the fastjet brand, added LCC credibility for investors, and received a very nice package — 5% of the share capital, a further 10% option, a royalty fee (5% of revenues) and €50,000 per month for consultancy services. As well as private investors, about 7% of fastjet’s stock was floated on London’s Alternative Investment Market (AIM); launched at 39p, the shares peaked at 48 early this year, since when the price has fallen precipitously to 6p in mid-September.

It is clear that African investment produced some nasty surprises for fastjet. Writing in the 2012 annual report, published in May, chairman David Lenigan wrote: “The Fly540 businesses acquired from Lonrho Plc have all seriously underperformed relative to expectations.”

The seriousness of the underperformance is starkly illustrated by the following table taken from the annual report:

| Revenue | EBITDA | |

|---|---|---|

| Tanzania | 3.6 | -13.8 |

| Angola | 13.1 | -4.3 |

| Ghana | 4.2 | -7.8 |

| Central | 0.2 | -15.9 |

| Total | 21.1 | -41.8 |

Also each country summary in the annual report referred to deep business problems and missing accounts. As a result the acquisition goodwill was adjusted down by $35m, and the auditors qualified the accounts.

In June David Lenigas stepped down as Chairman, temporarily replaced by CEO Ed Winter. This followed the purchase of Lonrho plc by FS Africa for a reported UK£175m; FS Africa is an investment fund set up by Rainer-Marc Frey, founder of Swiss hedge-fund group Horizon21, and Thomas Schmidheiny, who is, among many other things, a former director of Swissair.

Revised pan-African strategy

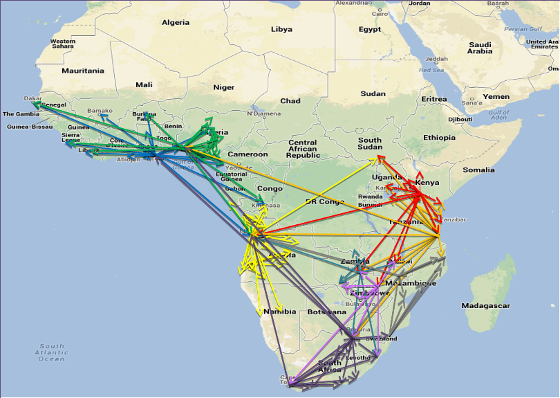

So without the framework promised by the 540 network, fastjet has had to modify its approach to achieving the pan-African airline shown in the map above (which was presented at the Terrapinn Low Cost carrier Congress held at Heathrow in September). There are now three models for growing fastjet.

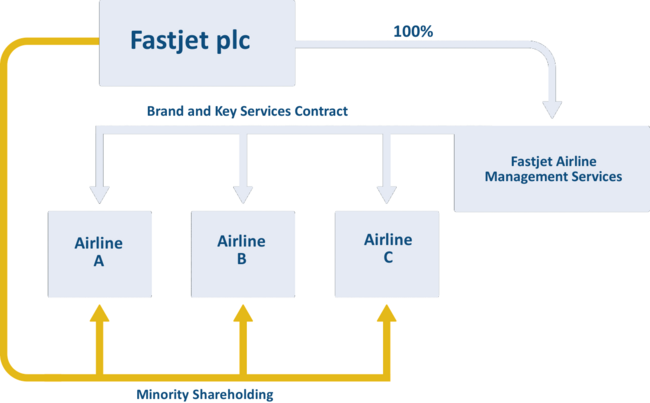

First, fastjet could set up a majority-owned carrier on the same lines as the Tanzanian operation in new countries — probably the preferred route but one likely to encounter bureaucratic and regulatory barriers.

Second, fastjet could take a minority shareholding in an airline and operate as a joint venture, with the partner providing local market expertise and compliance with ownership requirements. Air Asia has developed this model successfully, but Africa is more challenging.

Fastjet had advanced plans for a South African airline, 25% owned by fastjet and 75% by Blockbuster, a South African investment fund which was to have started this year. But this airline project has apparently been frozen as fastjet decided to concentrate on its first international services when it was awarded rights from Tanzania to South Africa, Zambia and Rwanda in June.

Flights to Johannesburg from Dar es Salaam were due to start on September 27th, posing a threat to SAA’s monopoly on this route. But nothing in Africa is that simple and on the launch day the South African authorities demanded “further documentation” from fastjet, causing the launch to be postponed.

Fastjet has also been exploring ways into the potentially huge Nigerian market, and has signed a MoU with RED1, a start-up, which according to its website, is “an innovative passenger airline, strategically positioned to bring the low cost, low fare revolution to the Nigerian people and Africa’s most dynamic region.”

Thirdly, fastjet is offering franchise-type agreements whereby African airlines can in effect buy fastjet’s LCC expertise, which is being packaged as Airline Management Service (AMS). The advantages of AMS, according to fastjet, are:

- Provides robust operational performance through group operational and safety systems and controls

- Maximises revenue by leveraging the brand

- Reduces risk for airline investors.

- Enables less experienced local airline management team to develop/operate a fastjet airline to the required international standards

- Provides the financial synergies of a large airline

- Creates efficiency through strategic guidance, business intelligence and management information from the whole group

Will Fastjet succeed?

The most obvious and painful lesson from fastjet’s experience is that there is no rapid way of setting up a transnational LCC in the continent given the current regulatory and bureaucratic barriers, and that airline capitalisation is likely to considerably greater than expected. The positive lesson is that fastjet has introduced effective LCC operating standards to Tanzania, and eventually, as in most of the rest of the world, the LCC model will help to break down barriers and undermine entrenched interests across sub-Saharan Africa — democratising air travel. The timescale question remains unknowable.

| Revenue | EBITDA | |

|---|---|---|

| Tanzania | 3.6 | -13.8 |

| Angola | 13.1 | -4.3 |

| Ghana | 4.2 | -7.8 |

| Central | 0.2 | -15.9 |

| Total | 21.1 | -41.8 |