Delta/Northwest merger: now looking more promising

September 2008

Delta and Northwest, the third and fifth largest US airlines, are hoping to complete their planned merger in the next few months, to create what they call "America’s premier global airline". The deal that initially offered little in revenue benefits and cost savings now suddenly looks rather promising, with a joint pilot agreement in place and no follow–up mergers in the pipeline. But what will be the impact on labour costs? And how sustainable are the revenue synergies in the longer run, given the shifting alliance landscape?

The all–stock transaction, announced on April 14th, was the first, and so far the only, merger deal between large US airlines since the US Airways/America West linkup in 2005. The combination, which will retain the Delta name, will be led by Delta’s CEO Richard Anderson. It will be headquartered in Atlanta, with some operations and staff functions in Northwest’s Eagan (Minnesota) base. The new Delta will have $35bn annual revenues and will be the world’s largest airline by passenger traffic.

The merger looks likely to secure stockholder and DOJ approvals. Shareholders will vote on the transaction on September 25 at special meetings to be held in Atlanta and New York. The deal received unconditional clearance from the EU Commission in early August. The DOJ is expected to follow suit this autumn — after all, there is minimal market overlap, Delta and Northwest already cooperate on some domestic routes, and the DOJ has already granted them permission to strengthen ties with their European SkyTeam partners. The airlines and the DOJ recently agreed on a timeline for the remainder of the antitrust review, which effectively guarantees a DOJ decision this calendar year. The airlines expect to be able to close the transaction by year–end.

Grounds for optimism

Back in April, the merger plan was not at all well received by investors because of its lack of synergies and capacity cuts. The initially projected $1bn annual synergies in later years seemed pitiful in light of the $3.5bn additional fuel bill that Delta and Northwest suddenly faced in 2008, and the initially projected $1bn merger–related expenses seemed reckless at a time when the focus needed to be on cash preservation. Investors aggressively voiced their disappointment, and Delta’s and Northwest’s shares plummeted.However, while significant execution risks obviously remain, in the past couple of months the Delta/Northwest merger plan has begun to look promising for a number of reasons — or, at least, it now seems like a reasonable strategy to deploy in the current industry environment.

The deal looks good, first because there are no other large–airline mergers on the horizon. Initially it was thought that there would be at least one follow–up merger, while some Washington lawmakers feared a "cascade of mergers". But soaring fuel prices, tightening credit and a slowing economy prompted other key players to reassess their priorities. Continental pulled out of merger talks with United at the end of April, and a month later United decided not to pursue a merger with US Airways.

Instead of industry consolidation, there will now be alliances. Continental and United have announced plans for a wide–ranging marketing partnership, which will involve Continental switching from SkyTeam to the Star alliance, while American hopes to tighten links with BA through an immunised transatlantic alliance.

There will not be other mergers in the current round, because the other airlines have missed the regulatory window. US airlines needed antitrust reviews for mergers before the current Administration, which is considered pro–merger, leaves office in January. Furthermore, the alliances will be a long time coming. The main threat, Continental/United, will not kick in until late 2009 at the earliest, because Continental has first to extract itself from SkyTeam and apply for regulatory approvals. Consequently, Delta and Northwest will have a significant advantage in the initial years as they consolidate.

Second, the Delta/Northwest plan now looks stronger because merger–related capacity cuts are no longer necessary. This is because the airlines, like their peers, have cut capacity sharply in response to the fuel and economic trends and will reduce capacity further if necessary.

Third, the Delta/Northwest plan looks good because the airlines have already achieved several milestones that should make the implementation of the merger smoother and the benefits likely to be realised earlier.

Most importantly, the critical pilot deal is in place. The airlines reached a pre–merger contract with both pilot groups in late June (ratified on August 11th), which also established the process for achieving seniority integration by the closing of the transaction (the pilots have agreed to submit to binding arbitration if necessary). This is believed to be the first time that a labour agreement has been reached in advance of a merger. It has removed one of the biggest hurdles, as pilot seniority has been a difficult issue in previous airline mergers (still unresolved at US Airways/America West).

The joint pilot deal, Delta’s mostly nonunion workforce and relatively good labour relations and strong support among Northwest pilots for the contract (an amazing shift from their earlier position) all bode well for a peaceful integration process.

Another major positive is that Delta and Northwest already have some connectivity between their reservations systems through SkyTeam. A recent report from Calyon Securities noted that labour and reservations systems usually account for over half of merger- related problems.

Delta and Northwest have already sorted out the post–merger organisational structure and named the entire executive team, in order to retain talent and "immediately begin capturing and exceeding the merger synergies following closing". The top 60 executives were named in mid–July. The top nine executives include five from Delta and four from Northwest. The 13–member board will have seven directors from Delta, five from Northwest and one from ALPA. During a 12–24 month transition period, Northwest will be a Delta subsidiary and run by Delta’s president/CFO Ed Bastian as CEO. Northwest’s current CEO, Doug Steenland, will step down once the merger closes and will take a seat on the new Delta’s board.

Fourth, the merger looks stronger now because it is expected to generate more synergies and be less costly to implement than initially estimated. Delta and Northwest have revised their financial forecasts — among other things, doubling the synergy estimates — as a result of a more detailed bottom–up analysis and after identifying substantial new opportunities.

Fifth, the merger should provide a good opportunity to raise substantial funding. While US airlines have continued to be able to raise cash from various sources, including the capital markets, and oil prices have fallen from the early–July peak, 2009 could still see a cash crunch if the economy slows significantly and oil prices remain at a high level. Merger–related financings — for example, equity injections or new credit facilities — would give the new Delta added financial flexibility in a tough industry environment.

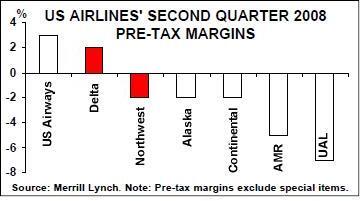

Delta and Northwest are probably the best–positioned of the US network carriers to meet the costs associated with mergers because of their successful recent Chapter 11 restructurings, which gave them strong balance sheets and competitive unit costs. Both airlines have transformed their business models and enhanced their networks, resulting in industry–leading revenue performance. In contrast with most of their peers, both Delta and Northwest earned profits before special items in the June quarter and are expected to continue to outperform the industry.

But outperforming peers does not ensure survival in the sort of economic environment that may materialise next year. The timing of the merger–related costs and benefits will be critical. Has the new Delta got a water–tight plan in that respect?

Merger synergies and costs

The other thing to watch for is labour expenses. Will the new joint pilot contract, which will increase Northwest pilots' pay by at least 30% over four years, be a financial burden? And what about all the other employee groups at both airlines that made deep sacrifices in bankruptcy?Delta and Northwest now expect the merger to generate $2bn in annual synergies by 2012, compared with $1bn when the deal was announced in April. Cash integration costs are expected to be around $600m over three years, compared with the initial estimate of "no more than $1bn".

The synergies are now expected to comfortably exceed merger–related costs even in the initial year. This is important in light of the need to preserve liquidity and it apparently reflects a promise made to shareholders to tie the cost of the integration to the value received. 2009 synergies (year one) are projected to be around $500m, compared with costs of $300m. 2010 and 2011 synergies are estimated at $1.1bn and $1.6bn, respectively, compared with costs of $200m and $100m. The full $2bn synergy run–rate, consisting of $1.4bn of network synergies and $600m of cost savings, is expected in 2012.

Roughly half of the $1bn increase in total annual synergies since the deal was announced came from refining earlier estimates. Better information was available about overhead reduction opportunities, technology, facilities overlap and improved efficiencies possible in airport operations and in selling costs. The station overlap synergy alone is well over $100m. Also, the joint pilot deal will make it possible to fully realise network and fleet synergies from day one, accelerating revenue capture. The remainder of the increase in synergies came from identifying structural opportunities, including the value of realigning affinity card strategies, optimising the RJ portfolio and creating a single powerful FFP.

The first–year synergies will be largely revenue play, resulting from the linking up of the networks and fleets. Being able fully to flow the fleet back and forth between the two networks was one of the rationales for why the airlines wanted the unified pilot deal and integrated seniority list done prior to closing.

In other words, Delta and Northwest hope that this merger will be different in that it will produce immediate revenue benefits. Linking up the networks will enable the airlines to compete more effectively and capture some market share from competitors.

The guiding principle in integration will be to focus on activities that generate a return on investment. Initial priorities will be to transition technology systems fully to a single platform, move to a single operating certificate and deliver a consistent customer experience by standardising the brand, employee training, uniforms, aircraft interiors and liveries. Some 26 integration teams have been hard at work and have made significant progress in a number of key areas.

Delta and Northwest have nicely complementary networks, both domestically and internationally. Of the 1,000–plus routes that the two airlines combined fly, only about 12 are the same. In addition, at airports where one or both are dominant, such as Atlanta or Detroit, there is no shortage of gates or slots and LCCs are already established, making it less likely that slot or gate divestitures are required. The merger combines Delta’s strengths in the South, Mountain West, Northeast, Europe and Latin America with Northwest’s leading positions in the Midwest, Canada and Asia. The plan is to maintain all hubs: Atlanta, Cincinnati, Detroit, Memphis, Minneapolis/St. Paul, New York JFK, Salt Lake City, Amsterdam and Tokyo Narita. There will be no specific capacity cuts as a direct result of the merger.

The downside is that the merger offers no cost savings from route and hub rationalisation. However, as many analysts have pointed out, industry conditions will determine the necessity for hub closures or further network restructuring. Both Delta and Northwest have already cut domestic capacity sharply and are prepared to cut more if necessary. There will be nothing stopping them from, say, closing a small hub in the future, regardless of promises made at the time of the merger.

Though not a priority, Delta and Northwest see significant opportunities to rationalise their RJ fleets and achieve cost synergies in regional operations. Between three owned regionals (Comair, Mesaba and Compass) and various contract operators, the new Delta will account for 40% of the current 50–seat RJ fleet in the US. There are likely to be additional reductions to the 100 RJs Delta is grounding this year. Although the three owned regionals will continue as separate companies, there are clear cost efficiency opportunities in terms of duplicated overheads and fleet commonality.

The biggest revenue gains are likely to be in international markets, where the large size and geographic diversity of the combination will boost business traffic. The new Delta will be the largest or second largest airline by traffic in all international markets out of the US. About 40% of its business will be international — expected to grow to 50% within a few years.

However, the merger will not really change the competitive landscape because the international market is so fragmented. A recent S&P report noted that the two largest participants, Air France–KLM and American, have less than 5% of the total market. But the merger will strengthen the transatlantic JV with Air France–KLM, which recently received antitrust immunity, and the SkyTeam alliance.

The synergy estimates include Delta’s and Northwest’s best estimates of the impact of the various changes on the alliance scene, including the loss of revenue associated with Continental leaving SkyTeam (the latter was described as "not material"). There appears to be upside to the figures, because the forecasts assumed that there would be one immediate follow–up merger. Also, the airlines believe that they have not included the full benefit of having 30% of the transatlantic market through the immunised AF/KLM/NW/DL alliance.

The projections include no impact from AA/BA, first because Delta’s and Northwest’s transatlantic operations focus on continental Europe. Paris will be the new Delta’s main European hub. Second, the airlines argue that the ten–year experience with the Northwest/KLM JV has shown that many of the benefits in such alliances build gradually as the parties get to learn to trust each other, find out what works, etc.

Otherwise the Northwest/KLM alliance has been a huge success. Delta executives noted in a recent conference call that Northwest’s profit margins across the North Atlantic are among the highest of any airline anywhere in the world. "Think about being able to leverage that across a network three times as big — it is a significant opportunity."

Sceptics would argue that the revenue synergies are not sustainable in the longer term, because demand is a zero–sum game. "One airline’s synergy is another airline’s lost share", observed JP Morgan analyst Jamie Baker in a recent report, adding that those losing share can be trusted to respond in kind.

One aspect of the deal that troubled many observers initially is that there will not be fleet synergies. Delta and Northwest have quite different fleets, including both Airbus and Boeing models and eight broad families of aircraft. It will be the largest and most complex mainline fleet in the US: nearly 800 aircraft, including everything from ancient DC–9s and MD–88s to highly attractive orders for A330s and 787s (for which Northwest is the US launch customer). Since the airlines are no longer in Chapter 11, they will not be able to rationalise the fleet very effectively.

Delta and Northwest have tried to put a positive spin on it by talking about the flexibility that they will have in being able to better match aircraft to routes, but that argument is not very convincing. The financial community appears to be in a "wait and see" mode in that respect, with some analysts suggesting that there may be some flexibility to pare the number of fleet types. Northwest has made useful headway in recent months in reducing its DC–9 fleet as part of the paring down of unprofitable flying; that fleet will decline from 94 at year–end 2007 to 61 by the end of 2008.

Delta executives say that the joint pilot agreement provides substantial financial and operational benefits that will far outweigh the cost of the contract. "It accelerates our ability to realise network synergies, expands our ability to code–share and, importantly, gets our pilot group behind the merger during this critical integration period."

The four–year contract, which runs through 2012, calls for pilot pay to be harmonised from day one, though retirement benefits will not be harmonised until the end of the contract. Delta successfully deployed a two–part approach. It first negotiated a deal with its own pilots: essentially a revision of an existing contract, which was extended through 2012, with the pilots agreeing to more flexibility (to facilitate the merger) in return for increased pay and a 3.5% equity stake in the combined company. Delta pilots will get pay increases of roughly 4% annually, meaning an incremental cost of about three points a year when previously contracted increases are included. The second part involved persuading Northwest pilots to come on board. Northwest pilots, who are more senior but lower paid, will receive at least a 30% pay increase over four years, as well as a 2.4% equity stake. The big concession that both pilot groups made was to agree to binding arbitration, if necessary, on the seniority issue prior to the closing of the merger.

Balance sheet considerations and financial prospects

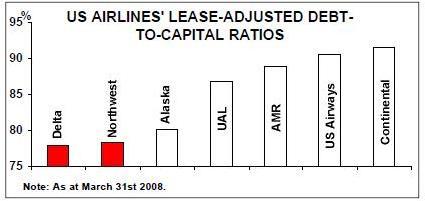

The new Delta is providing all US–based employees with an equity stake amounting to around 13.4%. The company has promised that the merger will result in fewer than 1,000 job cuts, affecting only management positions. There will be no involuntary layoffs for front–line employees. Delta has shed at least 3,000 employees this year through a voluntary programme.Even before any merger–related fund–raising, the new Delta will have one of the strongest balance sheets in the industry. Thanks to their Chapter 11 restructurings, Delta and Northwest have the lowest leverage among the US network carriers. According to a July 25th report by Merrill Lynch, Delta and Northwest had lease–adjusted debt–to–capitalisation ratios of 77.9% and 78.3% at the end of March — similar to JetBlue’s but lower than the 87%-92% ratios of UAL, AMR, US Airways and Continental.

Both airlines also have strong cash positions, which translates into better survival prospects. As of June 30, Delta had total liquidity of $4.3bn and Northwest had $3.7bn. The latest estimate, provided by Delta on August 25th, is that the combined cash position at year–end will be around $6bn. The airline said that it was comfortable with that position; however, it accounts for only 17% of annual revenues, so either some further pre–merger fund–raising is on the cards or there will be bigger merger–related transactions in the fourth quarter

Delta recently tapped a $1bn loan that was part of a credit line available upon Chapter 11 exit and also renegotiated its credit card agreements, to avoid any credit card hold–backs and ensure "full financial flexibility" to move forward with the merger. Northwest, in turn, issued $180m in new debt and drew down a credit facility. One of the most promising fund–raising avenues for the combined entity will be to do a forward sale of FFP miles, similar to — but on a much bigger scale — than the sale Continental completed in June. Of course, Air France–KLM may still be interested in investing $750m in an equity stake.

One of the key challenges that the new Delta will face in the longer term is financing significant re–fleeting, given the large numbers of old types in the fleet. In that respect the larger size — and hopefully stability — provided by the merger may be a positive move for the two airlines.

Restoring profitability will obviously be the key. Delta and Northwest are ahead of the pack also in that respect. They had the second- best pre–tax margins among the network carriers in the second quarter, 2% and -2% respectively (US Airways led the pack with a 3% margin). Excluding special items, both airlines actually reported small profits. They benefit from best–in–class cost structures and are now also achieving revenue premiums to the industry.