China's Big Three: The road to a Super PRC carrier?

September 2007

The "Big Three" PRC (Peoples Republic of China) airlines — Air China, China Southern and China Eastern — have been the beneficiaries of the government–mandated consolidation process in the aviation industry over the last few years, and have absorbed almost all of the medium–sized domestic carriers. But as competition between the Big Three increases, as well as from foreign airlines eager to tap into the growing Chinese market, so has financial pressure risen on the three largest airlines in China — and it’s likely that the structure of the Big Three will not remain the same for much longer.

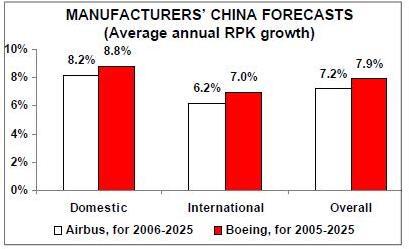

The good news for the aviation industry in general is that the Chinese economy is continuing its unprecedented growth. GDP increased by 11% in 2006 — its biggest rise in 11 years and the fourth year in a row of at least 10% growth — and this has been the key driver for traffic growth, both domestically and internationally. Although the latest market forecasts from the manufacturers (see table, opposite) see the Chinese domestic market growing at a faster rate than international traffic (and with Boeing being slightly more bullish about both markets than Airbus), both domestic and international markets are forecast to have sustained and high increases in traffic for the next two decades.

In the short–term, Chinese aviation is being given a substantial boost by the 2008 Olympic Games, which analysts believe will increase traffic to/from Beijing by as much as 20–25% in that year, with traffic expected to jump by about 15% in 2007 as a significant pre–Olympics effect starts to appear.

For the Big Three, the short–term effect of the Olympics and the long–term forecast growth in traffic is both good and bad news, because that growth is prompting unprecedented increases in capacity in the Chinese market by domestic and foreign airlines, causing fares and yields to fall.

Although all of the Big Three are now listed, they are effectively hampered in any meaningful efforts to strengthen their balance sheets by the Chinese government, which still has effective control over virtually everything that the Big Three do. Most visibly, orders are still placed in bulk with manufacturers "on behalf of airlines" by the Chinese government, but control extends much deeper than that, into senior managerial appointments, fare levels, route choices and virtually every major operational decision at the Big Three. On fares, for example, the government sets the overall fare level and airlines are only allowed to vary prices in a band up to 25% above and 45% below the state–set rate.

However, there are encouraging signs that some of the management at the three airlines is starting to feel confident enough to challenge the control of the government. For example, the Big Three are all lobbying the government to drop the VAT it imposes on imported aircraft, while the airlines are also complaining about high airport charges, increasing air congestion and inefficient air traffic control in China, the last two of which cost the industry around RMB 5bn ($0.6bn) in 2006, according to China Southern estimates.

The Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) has promised to invest RMB 50bn over the next five years in improving the country’s air traffic control system, but despite this pledge, Liu Shaoyong — chairman of China Southern — has called on the government to make a cash injection into airlines to compensate for air traffic congestion and high taxes. Shaoyong has gone further and publicly complained about China Southern’s lack of autonomy in deciding its strategy, including no input on what aircraft it buys and which airlines it has had to merge with (such as Northern Airlines and Xinjiang Airlines in 2005, both of which previously made losses).

For the moment, the Chinese government appears to be tolerant towards this growing criticism from within the domestic aviation industry, and indeed in January it was reported that the government planned to invest RMB 16bn ($2.1bn) into the Big Three in order to help them reduce debt levels (with $385m going to Air China, $848m to China Southern and $822m to China Eastern). However, with fuel prices falling over the first half of the year and the financial pressure easing slightly, the rumoured government cash boost may be postponed according to local sources — though it could be revived this autumn if fuel prices rise again.

But with or without further government cash injections — and despite other "structural" benefits of being a Chinese airline, such as the strengthening of the Yuan against the US Dollar, which significantly benefits domestic airlines — the growing competition in the aviation industry that the government has unleashed over the last few years is likely to have a profound effect on the future of the Big Three.

China Eastern is seen as the weakest of the Big Three financially, but now that a long–awaited investment by Singapore Airlines is going ahead (the two parties had been negotiating ever since July 2006), this may leave China Southern as the most vulnerable, as it will then be the last of the Big Three to find a strong, foreign strategic partner. Air China — thanks to its reliance on business traffic (accounting for 70% of all profits domestically), its equity links with Cathay Pacific and its dominant position at Beijing — is by far the strongest of the Big Three, and it may use its economic and political strength to force a merger with one of the two other airlines, and particularly before the government bows to growing external pressure to ease the restrictions on foreign investment. Currently foreign companies can own up to 49% of Chinese airlines, although no one company can own more than 25%, and if — or rather when — this is eased, foreign airlines are likely to rush into the Chinese market.

Air China

Rumours are even flying around in China that all of the Big Three may be merged into one so–called "super" Chinese airline, and although this is denied by everyone and anyone, it’s not beyond the realms of possibility that the Chinese government may see the creation of one mega–airline — which will instantly become the world’s largest carrier — as a powerful symbol of the growing strength of the country. The Beijing–based flag carrier has 32,700 employees and serves around 120 destinations (of which more than 40 are international). In January it completed the final moves in the complicated series of deals between it and Cathay Pacific, the China National Aviation Corporation (a Hong Kong–based government–owned holding company more commonly known as CNAC, which also owns 51% of Air Macau), CITIC Pacific and Swire Pacific. This entailed Air China taking 100% control of CNAC and de–listing it from the Hong Kong stock exchange after buying the remaining 30% it did not previously own from minority shareholders for the sum of HK$3.2bn (US$0.4bn). This followed the other components of the deal:

- Air China bought 10.16% of Cathay Pacific from CITIC Pacific (an investment company backed by the Chinese government and listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange) and Swire Pacific for HK$5.4bn (US$694m), thereby taking Air China’s direct and indirect (via CNAC) stake in Cathay to 17.5%.

- Cathay bought 1.2bn new H–shares (traded on the Hong Kong market) in Air China for HK$4.1bn, thus doubling its stake in Air China from 10% to 20%.

- Cathay purchased the remaining 82.2% of Hong Kong–based Dragonair that it didn’t own from CNAC (43.3%), CITIC Pacific (28.5%), Swire Pacific (7.7%) and others (2.7%) for a total of HK$8.22bn (US$1.06bn) in cash and new Cathay shares. This part of the deal was finally completed in September 2006 (when the CNAC shares were bought).

- Air China and Cathay signed a partnership agreement, including: reciprocal sales (with each airline selling flights for the other in its "home territory"); an extension of existing code–sharing; the launch of joint venture routes (with profit sharing) on selected Hong Kong–mainland China destinations; and the setting up of a cargo joint venture in Shanghai.

These deals give Air China a healthy chunk of a profitable airline (Citigroup estimates a RMB 600m/US$77m boost to revenue thanks to the tie–up with Cathay) and — crucially — access to feed into Beijing and Shanghai from Hong Kong business travellers. In January this year Air China and Cathay also changed their arrival and departure times at Hong Kong to allow easier connectivity for passengers, so that no passenger has to wait for more than an hour for a connection.

Air China IPO–ed on the London and Hong Kong exchanges in 2004 (raising US$1.1bn), but in August last year it also listed on the Shanghai stock exchange in an exercise that proved that not every airline listing in the Chinese aviation market is paved with gold. Air China intended to raise RMB 7.97bn (US$1bn) by selling 2.7bn new shares, equivalent to 22.25% of the enlarged equity, but the so–called A–share issue was set at an indicative price that was simply too high (with a multiple of 8.7 times 2005 earnings). A poor reception from potential investors quickly forced the airline to scale back the domestic IPO by just under 40%, from 2.7bn shares to 1.64bn (now representing 14.8% of the carrier’s equity), and thus raising RMB 4.59bn (US$577m) from institutional and private investors — some RMB 3.38bn (US$425m) less than it was aiming to raise originally.

After the debut day (August 18th), the share price started to drift down from the issue price of RMB 2.8, which forced Air China (via its parent, the government–owned China National Aviation Holdings — known as CNAH — which still has a majority stake in Air China) to spend many tens of millions of dollars in buying back its shares in order to shore up the stock.

Air China’s troubled Shanghai float was partly a case of bad timing (it went to market after the Chinese government gave permission for domestic IPOs to restart in May after a previous year–long ban, so lots of companies floated at a time when there was a general weakness in the Shanghai market), and partly because the airline and its advisors were just too greedy in setting a high price at a time when analysts were nervous about the price of fuel and the 2006 profit level.

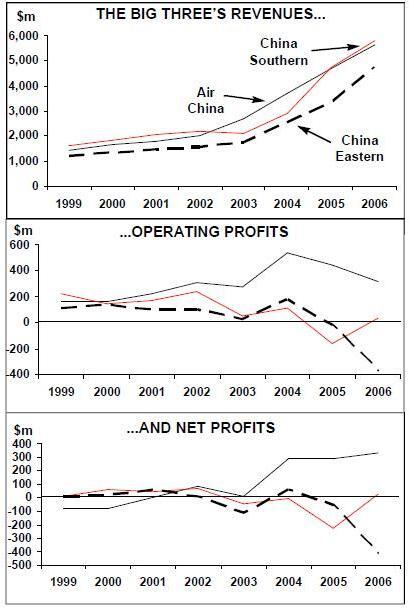

In 2006 Air China’s revenue (under international accounting standards, which differ significantly from the Chinese standards that the Big Three use for quarterly results) rose 21% to RMB 44.9bn ($5.6bn), while net profits rose 15% to RMB 2,688m ($338m). However, this was lower than some analysts expected (Merrill Lynch, for example, had forecast net profits of RMB 3.25bn), due largely to higher staff, maintenance and fuel costs. Fuel expenditure rose by 33.4% in 2006 to RMB 15.7bn, accounting for 37% of all costs, and as a result Air China is now increasing its hedging operation; it hedged 44% of fuel costs in 2006, but this will rise to 49% this year. The net profits also included a gain of RMB 1.6bn from selling the 43% stake in Dragonair to Cathay. At the operating level, profits fell by nearly one–third, to RMB 2.51bn ($316m).

Nevertheless, Air China has consistently been more profitable than both China Southern and China Eastern over the last five years, and it expects to post strong profit growth for the first half of 2007. Its rivals point out the inherent advantages that Air China has in being the flag carrier, such as being merged with stronger domestic airlines than its Big Three rivals, or the benefits of substantial government travel out of Beijing.

Indeed, at Beijing, Air China has an estimated 44% market share of traffic to/from the airport. The flag carrier has around 130 aircraft stationed there and it will benefit particularly from the new third terminal and runway that will open at Beijing at the end of 2007. The new terminal will double the capacity of the airport, and half the new facility will be devoted to Air China and its domestic partners (Shenzhen Airlines and Shandong Airlines) and the other half for international carriers.

In 2006 Air China launched routes from Beijing to Delhi, Madrid and Sao Paolo, and among the destinations that Air China has either started or plans to launch out of Beijing this year are St Petersburg, Saipan and Sapporo. Air China also launched a Beijing–San Francisco service in April, which joined existing routes to New York and Los Angeles, and more routes are likely following the new aviation agreement signed between China and the US in May, which will double the number of passenger flights allowed between the countries over the period to 2012 (from the current 266 flights a week).

Air China also wants to expand into more "secondary" international destinations, thereby building up Beijing as an international hub, and it is planning to build up Dubai as another hub operation from 2008, linking flights from Asia to not only Europe but to Africa and the Middle East as well, as part of what Air China calls a "twin hub" operation.

Air China’s international ambitions will also be realised when it finally joins the Star global alliance, to which it was formally invited in May this year. Air China hopes to become a member before the end of the year, but the move will be accompanied by further speculation that this may lead to a merger with Shanghai Airlines, which will also join Star at around the same time (and which will enable a "dual hub" strategy for Star in China). A tie–up between the two has been rumoured for some time, and Air China is keen to boost its presence in Shanghai in a direct challenge to one of its key competitors, Shanghai–based China Eastern. Air China already stations 30 aircraft at Shanghai and has a 20% market share out of the airport, compared with the 30% of China Eastern, but it plans to considerably strengthen its Shanghai base within the next year, with as many as 1,000 employees stationed there.

Shanghai will also be the headquarters of the new cargo joint venture with Cathay, reported to be launching by the end of 2007, with 51% owned by Air China and 49% by Cathay, although first Air China may buy out its existing partners in Air China Cargo, its current cargo operation, who are CITIC Pacific (which owns 25%) and Beijing Capital International Airport (which owns 24%).

The tie–up with Cathay will be followed by the opening of a new cargo terminal base in Shanghai, and this deal kills off any lingering hopes that China Eastern had of a cargo partnership with Air China. Both Air China and China Eastern face growing cargo competition, including Shanghaibased Great Wall Airlines — which launched in 2006 and is owned 25% by Singapore Airlines Cargo — and Shenzhen–based Jade Cargo International, which was launched in 2006 and is owned 25% by Lufthansa Cargo.

In terms of passenger traffic, Air China forecasts a 15% rise in RPKs in 2007, ahead of a planned 12% rise in capacity, and it says premium load factor should rise by 10%, thanks to booming business travel and the pre–Olympics effect. This will come on top of the 14.2% rise in passengers carried in 2006, to 34m, when a 12.7% rise in capacity was bettered by a 15.5% growth in traffic, resulting in a 1.9 percentage point increase in load factor, to 75.9%.

Air China also owns 25% of Shenzhen Airlines, which operates a fleet of 47 A320s and 737s, and has 29 narrowbody aircraft on order as it plans for rapid expansion. Shenzhen scored a coup in 2006 when it hired Li Kun away from China Southern to become its president. Kun had been with China Southern for 27 years, and was the first senior airline executive to leave one of the Big Three for a private airline (albeit one part–owned by Air China). Based in the southern city of Shenzhen, close to Hong Kong, 65% of the airline was auctioned off by the government to two private companies in May 2006 (with Air China unsuccessful in its bid to acquire a bigger stake). Air China also owns 22.8% of Shandong Airlines, which operates 30 aircraft on mostly domestic routes and which has 13 737s on order.

Air China’s fleet currently stands at 187 aircraft, with 35 new aircraft added in 2006 and 24 aircraft arriving this year. Around 65% of the total RMB 16.9bn capex at the airline in 2007 will be used for fleet expansion, and Air China will continue with high levels of fleet investment for the foreseeable future, with around 25 aircraft being added every year until the end of the decade.

China Southern

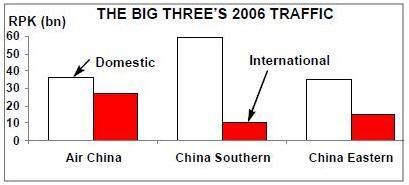

However — assuming that Air China doesn’t merge with one of its Big Three rivals — even this expansion will not enable the flag carrier to catch up with the fleets of its two main rivals. Guangzhou–based China Southern has 45,500 employees and is by far the largest of the Big Three in terms of fleet size, with 279 aircraft operating to more than 70 domestic and 50 international destinations. In terms of RPKs, it is the largest of the Big Three in the domestic market, but has the least amount of international traffic (see chart, opposite).

In 2006 China Southern returned to profitability for the first time since 2002, thanks to rising demand, selected cost–cutting and the revaluation of the Yuan against the US Dollar, with net profits of RMB 204m ($25.6m) compared with a $229m net loss in 2005. Revenue rose 22% to RMB 46.2bn ($5.8bn) in 2006 (passenger yield rose 9.1% in the year), and operating profits reached RMB 312m ($39m), compared with a RMB 1.3bn ($162m) operating loss in 2005.

In the first–half of 2007 China Southern’s revenue rose 19% and net profits reached $22m (compared with a $108m loss in 1H 2006), and the airline forecasts that it will carry as many as 60m passengers this year, which would represent a 22% rise on 2006, when its passengers carried rose 11.5% to 49.2m. ASKs increased by 9.8% in 2006, and with RPKs up 12.4% load factor rose 1.6 percentage points, to 71.7%. The strongest passenger growth in 2006 came from international routes — up by 13.2% — while domestic RPKs grew 9.8% and Hong Kong traffic fell by 0.5%.

As China Southern’s chairman likes to point out, in previous years the airline had been hampered by the "mandates" of the government, and losses increased in 2005 despite a 60% jump in revenue thanks largely to the integration costs of China Northern Airlines and Xinjiang Airlines, which were folded into China Southern as part of the government’s consolidation plan. Despite floating on the Hong Kong and New York exchanges in 1997, the government still owns a 50.3% stake in China Southern, and the airline may be more vulnerable to further government–mandated strategic moves as it will soon be the last of the Big Three without an equity link with a strong foreign airline. A tie–up with Air China would make sense strategically, giving the flag carrier access to a huge domestic network and giving China Southern a large international route network.

But in the absence of any such megamerger for the moment, according to unconfirmed sources China Southern is searching urgently for an international partner of its own choice, and Air France–KLM is tipped as the most likely candidate by some analysts. China Southern is believed to be negotiating an extensive passenger code–share with Air France–KLM at present, and in any case — after many years of speculation — China Southern will formally join SkyTeam before the end of 2007. The airline signed an MoU to join the alliance back in 2004, with the intention of joining in 2006, but this timetable was not achievable, and this year China Southern has been urgently upgrading many of its IT systems and other processes in order to meet the standards required by SkyTeam.

Whether SkyTeam membership will lead to an equity tie–up with Air France–KLM is yet to be seen, but later this year China Southern will also start a comprehensive partnership with SkyTeam member Continental, including code–sharing on both international and domestic flights (from November) as well as reciprocal FFPs (from September).

In preparation for SkyTeam membership, China Southern has been carrying out a major expansion of its international network this year, with at least 10 new routes either launched or due to start before the end of 2007, including routes from Guangzhou to Dubai, Phuket, Siem Reap (Cambodia), Yangon (Myanmar), Vientiane (Laos), New Delhi, Sapporo and Sendai (Japan), and from Urumqi to Jeddah (the first passenger route between China and Saudi Arabia) and flights from Shenyang to Nagoya. In December a daily service will be launched between Beijing and Paris, in competition with Air France and Air China.

China Southern is also becoming more aggressive in its approach to its main rivals. In the summer of last year China Southern finally opened up a hub operation in Beijing, which it had long been lobbying the Chinese government for permission to do in time for the 2008 Olympics. It already has its own terminal at Beijing airport (Terminal One) for domestic operations only, and the 40 or so routes there carry around 8m passengers to/from Beijing and account for at least 10% of the airline’s total revenue. China Southern is now spending around $150m on upgrading its Beijing facilities for future 787 and A380 operations from 2008 and 2009 respectively.

After Guangzhou and Beijing, China Southern has secondary hubs at Urumqi (in north–east China) and Shenyang (in the north–west) that enable domestic coverage of the whole country, and this year is also looking to invest $100m in setting up an airline based in Chongqing, in the south–west of China. This will be launched in partnership with the regional government, with plans initially for three A320s supplied by China Southern operating regional routes.

China Southern also holds stakes in China Postal Airlines (49%), Guangxi Airlines (60%), Guizhou Airlines (60%), Shantou Airlines (60%), Sichuan Airlines (39%), Xiamen Airlines (60%) and Zhuhai Airlines (60%). Xiamen Airlines currently operates 45 aircraft and has the largest order book of any of the second–tier carriers in China, with 30 new generation 737s on order, including 25 737–800s ordered this summer for delivery in 2011–2013. Sichuan Airlines is also a second–tier airline, with a fleet of 35 aircraft (all but five of which are A320 family models), with 12 A320 family aircraft on order.

As with its rivals, China Southern is looking to strengthen its cargo operations in the face of growing competition, and is currently analysing a cargo joint venture with Air France. Talks with Korean Air in 2006 over a cargo joint venture came to nothing and Korean Air instead set up a Chinese cargo airline in partnership with a local logistics company, but a tie–up with Air France is seen as more likely to come to fruition. In relative terms China Southern’s cargo operation has been small compared with its Big Three rivals, with most of its freight carried in the holds of passenger aircraft, and with its only dedicated cargo aircraft being two 747–400Fs. However, US–based B/E Aerospace has just begun to convert six A300s into freighters, which will be completed by the end of 2007 and be used on Asian routes.

China Eastern

Altogether China Southern has 98 aircraft on order. It agreed a further $1.3bn borrowing facility from the state–owned China Construction Bank, and this will be used partly to finance an order book that includes 50 A320s placed last year, for delivery in 2009 and 2010, and a substantial order for 55 737–700s and -800s that the airline is likely to place with Boeing this autumn. China Southern has five A380s on order, and although it is a major disappointment that the first A380 will not be delivered until 2009 — after the Beijing Olympics — Chinese government sources say the airline will receive $250m from Airbus as compensation. Shanghai–based China Eastern has 30,000 employees and operates a fleet of 207 aircraft to more than 100 destinations, with around 40 of those outside China.

In 1997 China Eastern became the first Chinese airline to list on a foreign market, when it debuted on the New York and Shanghai markets, and currently it is 61.6% owned by the government. But despite its early listing, China Eastern is financially the most vulnerable of the Big Three, as its book value halved in 2006 after a year of heavy losses. In 2006, although revenue rose 41% to RMB 37.9bn ($4.7bn), operating profit leapt from $16m in 2005 to RMB 3bn ($376m) in 2006, and its net loss rose from $57m in 2005 to RMB 3,314 (-$416m) in 2006. This was due largely to the integration of three airlines in 2005 and 2006 (Yunnan, Northwest and Wuhan) which resulted in large increases in costs, with fuel up 53% to RMB 13.6bn, salaries up 47% and maintenance up 91%.

With the addition of the merged airlines, in 2006 passengers carried rose 44.2% to 35m (with domestic passengers up 52.3% to 27.7m, international by 27.7% to 4.8m, and Hong Kong up 7.2% to 2.4m). RPKs grew by 38.1%, ahead of a 34.4% increase in ASKs, resulting in a 1.9 percentage point rise in load factor, to 71.3%.

In October last year China Eastern announced an unexpected change in president, with Cao Jianxiong replacing Luo Chaogeng, and although the airline says it expects to return to profit this year (it reduced its losses in the first–half of 2007), China Eastern’s immediate future depends on the long–anticipated investment by Singapore Airlines and Temasek Holdings, the Singapore government’s investment vehicle.

Negotiations had been taking place since the summer of 2006 over a joint purchase by SIA and Temasek of a minority stake in China Eastern. In early September the deal was finally unveiled, with SIA and Temasek agreeing to buy 24% of China Eastern for US$916bn. China Eastern’s shares had been suspended since May, and now that a deal has been agreed this gives a crucial boost to China Eastern, enabling it to reduce debt and to obtain access to more professional management. Equally, the agreement enables SIA to get into the Chinese market (although SIA has not had a great track record in previous investments in foreign airlines).

However, some analysts are concerned the deal will not create as many synergies between China Eastern and SIA as there are between Air China and Cathay, as there is relatively little overlap between the net–works of the two airlines. That’s perhaps why SIA brought in a co–investor, allowing its own investment to be less than 20% — which means that any short–term losses in China Eastern do not have to be taken onto its financials. For China Eastern however, the link with a strong foreign airline is more critical. Last year it reportedly also talked with Emirates and Japan Airlines, but no deal subsequently emerged, and if the deal with SIA had fallen through, China Eastern would have remained vulnerable.

Despite code–sharing with no fewer than 18 airlines (including American and Air France), China Eastern is also the last of China’s Big Three to commit to a global alliance, and with its rivals linking up with Star and SkyTeam, the most obvious candidate for China Eastern is oneworld. Whether it needs to agree a deal with oneworld more urgently than oneworld needs an agreement with China Eastern is open to debate, but the situation is complicated by the stake in China Eastern by Star member SIA.

Although oneworld insists this will not be a problem (given that oneworld’s Cathay has a stake in Star–bound Air China), unconfirmed local sources say that China Eastern could well be lured into Star after all, with the SIA investment putting heavy pressure on China Eastern executives to turn down oneworld.

If that happens, this would leave oneworld with a substantial hole in its global network, that will not be filled by Dragonair (now owned by Cathay) which is joining oneworld as an affiliate later this year, and that’s why oneworld may be hedging its bets by also talking with Hainan Airlines, the fourth largest airline in China.

The prospect of China Eastern membership of Star is all the more intriguing as it would fuel rumours about an Air China- China Eastern merger. There’s little doubt that Air China is intensely interested in Shanghai (see page four), which is the financial capital of China, but on the other hand Cathay is unlikely to want its new investment to get into bed with China Eastern, particularly as Shanghai Airlines (which code–shares with Air China) is soon to become a member of Star as well, and Shanghai Airlines is a fierce competitor with China Eastern.

The wishes of Cathay may be immaterial however, because if the Chinese government wants a merger to go ahead, it will happen. Perhaps most pertinent is that fact that CNAH — Air China’s parent company — has been increasing its stake in China Eastern (reaching 8.3% in May), and a full "bid" for China Eastern would involve only a domestic reshuffling of stakes held by CNAH and China Eastern Air Holding Corporation, the government–owned parent of China Eastern that will retain a 51% stake in China Eastern post the SIA/Temasek investment.

Where this all leaves China Eastern is hard to say, but in the meantime at least it is launching a counter attack on Air China via a build up of assets at Beijing, where it has formally applied to the CAAC to build a hub operation. China Eastern currently has an 11% market share of passengers to/from Beijing, but has been endeavouring to increase its presence there in the run up to the Olympics — although it is someway behind the activities of China Southern, which has its own terminal. Nevertheless, it has applied to the CAAC to start a daily service from the capital to London, competing against Air China and British Airways, as well as a route from Beijing to Okayama in Japan via Dalian. China Eastern currently has a handful of routes from Beijing to Asian destinations, including Nagoya in Japan (via Qingdao), Tokyo and Delhi.

China Eastern is also increasing international routes from Shanghai, which connect with the airline’s large domestic network. This year routes are being launched from Shanghai to Males (Maldives) and Johannesburg, while a non–stop route between Shanghai and New York JFK was started in December 2006, competing against a service from Air China and launched just ahead of a probable wave of new services from US airlines such as Continental, American, Northwest and United that are looking to increase direct routes into China given the recent bilateral (and which makes pressure on China Eastern to join a global alliance even more intense).

In terms of its fleet, approximately 20 aircraft will be added in both 2007 and 2008, with a total of 91 aircraft currently on outstanding order. These include 15 787–800s, to be delivered from June 2008 to 2010, while 30 more A319s and A320s were ordered in 2006, for delivery in 2008–2010. Three A300–600s are being converted into freighters by EADS this year for China Cargo Airlines, China’s first dedicated cargo airline, in which China Eastern owns 70%.

| Boeing | Boeing | Airbus | Airbus | ||||

| Narrowbodies | Widebodies | Narrowbodies | Widebodies | Other | Total | ||

| Air China | 96 (25) | 36 (15) | 35 (30) | 15 (11) | 5 | 187 | (81) |

| Air China Cargo | 9 | 9 | |||||

| Air Hong Kong | 8 | 8 | |||||

| Air Macau | 13 | 3 | 1 | 17 | |||

| Cathay Pacific | 58 (24) | 45 (5) | 103 | (29) | |||

| Changan AL | 6 | 4 | 10 | ||||

| China Cargo AL | 1 (1) | 1 | 6 | 8 (1) | |||

| China Eastern AL | 59 (20) | 3 (15) | 82 (45) | 30 (8) | 33 (3) | 207 | (71) |

| China Postal AL | 5 | 5 | |||||

| China Southern AL | 111 (20) | 12 (10) | 96 (54) | 11 (14) | 49 | 279 | (98) |

| China United AL | 11 | 32 | 43 | ||||

| China Xinhua AL | 16 | 16 | |||||

| Deer Jet | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Donghai AL | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Dragonair | 7 | 15 | 16 | 38 | |||

| East Star AL | 3 (7) | 3 (7) | |||||

| Great Wall AL | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Guizhou AL | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Hainan AL | 29 (29) | 5 (8) | 7 (27) | 27 (100) | 68 (164) | ||

| Hong Kong AL | 6 | 6 | |||||

| Hong Kong Express AW | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Huaxia Airlines | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Jade Cargo Int'l | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | |||||

| Jet Asia | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Juneyao AL | 4 (5) | 4 (5) | |||||

| Lucky Air | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Oasis Hong Kong AL | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Okay AW | 4 | 4 | |||||

| Shandong AL | 20 (13) | 10 | 30 | (13) | |||

| Shanghai AL | 36 (15) | 7 (9) | (5) | 7 | 50 | (29) | |

| Shanxi AL | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Shenzhen AL | 36 (10) | 11 (19) | 47 | (29) | |||

| Sichuan AL | 30 (12) | 5 | 35 | (12) | |||

| Spring AL | 7 | 7 | |||||

| Tianjin AL | 14 | 14 | |||||

| United Eagle AL | 4 | 4 | |||||

| VIVA Macau | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Xiamen AL | 45 (30) | 45 | (30) | ||||

| Yangtze River Express | 6 | 6 | |||||

| Total | 517 (162) | 149 (85) | 311 (204) | 129 (38) | 178 (103) | 1,284 (592) | |