SkyWest and FLYi: RJ operators, contrasting fortunes

September 2005

As fuel prices have again surged in recent weeks, creating havoc in the legacy carrier sector in the US, two of the nation’s largest regional jet operators find themselves in oddly contrasting positions.

One of those companies, FLYi, the parent of Independence Air, is in a cash crisis, after struggling for over a year. FLYi is a likely near–term Chapter 11 candidate and, unlike the legacy carriers, is probably also headed for liquidation. "The end appears to be near", noted one Wall Street analyst when downgrading the company to "sell" on August 15.

By contrast, on that same day, cash–rich SkyWest announced a US$425m acquisition of Atlantic Southeast Airlines (ASA), one of Delta’s two wholly owned regional subsidiaries. SkyWest has been consistently profitable, with one of the strongest balance sheets in the industry. The ASA purchase, which closed on September 8, has nearly doubled its size, making it the largest regional carrier in the US with a combined fleet of 372 aircraft.

Why the contrasting fortunes? Because the two airlines have adopted business models that have dramatically different fuel price risk exposures. SkyWest has opted to continue working with the legacy carriers, sticking with the safe fixed–fee feeder model that eliminates fuel price risk and guarantees profit margins.

FLYi, in turn, disillusioned by the regional model and tired of the hassles of working with bankrupt partners, has rejected all that in favour of being an independent low fare carrier — probably the worst possible time to try such a strategy with a fleet of primarily 50–seaters.

FLYi's ill-fated transformation

FLYi’s troubles date back to its decision, announced in mid–2003, to transform itself from a regional carrier into an LCC with a large independent hub operation at Washington Dulles. After previously operating as a feeder for United and Delta, and formerly known as Atlantic Coast Airlines or ACA, FLYi launched Independence Air in June 2004, initially with 50–seat CRJ–200s and since late 2004 also with 132–seat A319s. The airline terminated its United Express and Delta Connection operations by August and November 2004, respectively.

The past year has seen a complex fleet transformation, which has included retiring all 24 J–41 turboprops, passing 33 328JETs to Delta, returning 24 CRJs to lessors and adding 12 leased 132–seat A319s. In addition to the A319s, Independence Air currently operates 58 CRJs — down from a peak of 112 in 2003.

The airline uses the CRJs to offer frequent service on short haul routes and the A319s in larger, primarily long haul markets, including coast–to–coast. Currently, 44 destinations are served around the country.

The product is in the up–market JetBlue mould, described as "reliable and easy to use air transportation with excellent customer service".

FLYi’s efforts met with considerable scepticism right from the start, with the investment community being concerned about the high level of risk and untested economics. Those misgivings and the airline’s reasons for making the switch were examined in a briefing in the September 2003 issue of Aviation Strategy and further discussed in the May 2004 and November 2004 issues. In essence, FLYi’s leadership felt that the fixed–fee economics were deteriorating and that growth opportunities in the regional sector were diminishing.

Independence Air was extremely well funded to start with, with cash reserves of US$345m in June 2004. But, after a year of horrendous cash burn, unrestricted cash had dwindled to only US$66m at the end of June. The few analysts that still follow FLYi have concluded that, barring some miraculous rescue, the company is on course to run out of cash in the fourth quarter and therefore is likely to seek Chapter 11 protection before mid–October.

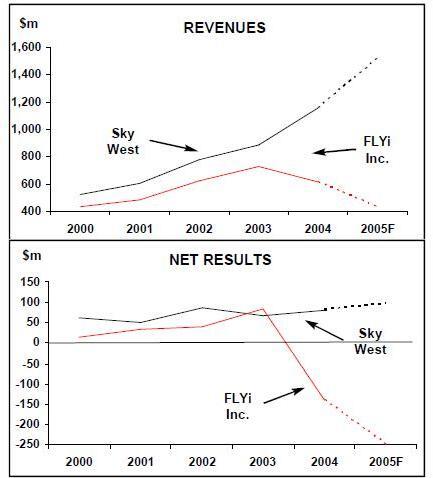

FLYi’s revenues have declined by 41% in the past two years, from US$730.5m in 2003 to an estimated US$430.5m this year. The company posted a US$139m net loss before restructuring charges for 2004, representing a negative 22.6% net margin and contrasting with 2003’s positive 11.3% margin.

The First Call consensus estimate is that FLYi is headed for a net loss before items of US$250m, or 58% of revenues, in 2005.

In addition to the tough revenue environment and fuel (FLYi has had no fuel hedges), the airline has blamed the past year’s losses on high transition and rebranding costs. It has an infrastructure and an overhead supporting a much larger operation. Also, FLYi has attracted less traffic than it had predicted, due to unexpectedly intense competition from United and others. Because of that and its own significant capacity addition, its load factors remained in the 40s or 50s until recently.

There have seen signs recently that FLYi is finally establishing itself in the marketplace. Its load factors have recovered dramatically — July’s was 79% and August’s 72.2%. Also, the airline has ranked high in customer satisfaction surveys.

There was also reason to hope that increased use of the larger Airbus aircraft would help reduce losses — after all, like many of the US regional airlines, ACA was a lean and highly efficient operation and therefore potentially successful as an LCC.

In addition to having much lower seat–mile costs than the CRJs, the A319s have given FLYi access to attractive new markets.

However, the recent load factor improvements appear to have come at the expense of yield. And the cost benefits resulting from increased A319 usage are totally obscured by an unexpectedly sharp fall in unit revenues. In fact, the negative CASM–RASM gap has widened over the past year.

In the second quarter, RASM plummeted by 48.3% year–over–year to 9.1 cents, while CASM fell by a lesser 31.5% to 13.7 cents.

In an attempt to remedy the problem, FLYi has decided to test the A319s in different markets. Beginning this month, the airline is cutting back transcontinental service (terminating Dulles–San Jose) in favour of using A319s in some of the higher–yield, short haul East Coast markets such as Boston. The airline has also reduced its total daily flights by 15% in the September schedule.

To conserve liquidity, in mid–August the airline deferred deliveries of six A319s that were scheduled for 2006. All of the 16 A319s on firm order will now be taken between the second half of 2007 and 2009.

This facilitated an immediate US$31.2m cash refund (for pre–delivery payments already made) and deferred US$11.5m in further payments that would have been required this year. (In April FLYi exercised its right to cancel all of its 34 firm CRJ orders from Bombardier, which had been tied to the United Express contract.) According to its latest quarterly report, FLYi is "re–evaluating the scope and nature of its Independence Air operations" and continuing to evaluate ways to address its liquidity needs. Initiatives under consideration include asset sales, such as the three remaining owned 328JETs and their spare parts inventory, additional issuance of equity or debt, and further debt or lease restructuring.

FLYi had US$253.8m of long–term debt at the end of June.

However, there may not be any realistic options left in respect of debt or leases, because FLYi has already undertaken extensive restructuring this year.

The company averted bankruptcy in February, when the majority of its CRJ lessors and debt providers and J–41 lessors agreed to restructure its lease and debt liabilities.

Merrill Lynch analyst Mike Linenberg has estimated FLYi’s third–quarter cash burn at US$600,000 per day, which would reduce unrestricted cash to just US$12m by the end of September. Including the A319 deposit refund, cash would amount to US$43m, which Linenberg noted is a "dangerously low liquidity level to enter the December quarter, particularly if oil prices stay high".

Tough new revisions to Chapter 11 laws will take effect on October 17, so like other prospective bankruptcy candidates, FLYi is expected to file before that date. FLYi’s shares, listed on the Nasdaq (but currently under notice of non–compliance with listing requirements) have been trading at bankruptcy levels for quite some time.

The share price fell steadily from the US$10–level in late 2003 to around US$4 in October 2004, when it plummeted to the US$1.50 level due to bankruptcy speculation.

The price fell below US$1 in April and since early August has languished below 50 cents. Investors have had plenty of warning and many have got out in recent months. Wellington Management, one of the largest shareholders, liquidated its stake in FLYi in June.

FLYi’s chances of attracting additional capital or emerging from Chapter 11 are much weaker than other airlines', because there are grave doubts about the viability of its business model. Arguably, the airline has not had a chance to properly demonstrate the strategy because of the fuel environment — among other things, the plans called for a much larger number of 50–seat CRJs. However, it is probably fair to conclude that 50–seat RJs are not viable for an LCC in the US, because the domestic market is so competitive and because a high fuel price environment is probably here to stay.

In many ways, the latest A319 deferrals have been the last straw, convincing analysts that FLYi will not achieve a competitive cost structure. Calyon Securities analyst Ray Neidl suggested that the A319 deferral "extinguishes the last possibility for management to make the business model work".

There have been repeated calls from analysts and investors for FLYi to give up LCC ambitions and go back to being a regional. When allocating new contracts some months ago, United also made it very clear that it would welcome FLYi back as a feeder (in the process getting rid of an irksome competitor at Dulles). This might still be possible as an alternative to liquidation, though the opportunities are diminishing as other regional airlines have adopted aggressive growth strategies. Many people believe that the regional sector is ripe for consolidation.

Unfortunately, FLYi is too small to have much positive impact on industry capacity if it disappears. But there would be positive impact on pricing, because FLYi has been particularly disruptive on that front as it has desperately sought to fill its aircraft.

SkyWest's ASA purchase and growth opportunities

Utah–based SkyWest, which operates under fixed–fee feeder contracts for United and Delta, typifies the traditional successful US feeder airline. Effectively a "major" with US$1.2bn revenues in 2004, the company has been consistently profitable — last year it earned a net profit of US$82m, representing 7% of revenues. The First Call consensus forecast for 2005 (before inclusion of ASA’s results) is a net profit of $97.4m or 6.4% of revenues.

While SkyWest and other US regional airlines have seen some deterioration in fixed–fee economics as their legacy partners have had to achieve cost savings, the impact on profit margins has been marginal. A report from Raymond James & Associates estimates that the guaranteed pretax profit margin in SkyWest’s latest contract with Delta is 9%, which apparently is the new market rate. Previously, 10–11% seemed to be the norm.

Also, regional carriers now seem content in working with legacy partners that are in Chapter 11. When announcing the ASA deal, which makes SkyWest Delta’s largest regional partner, SkyWest said that it was not concerned about Delta’s potential bankruptcy because of its successful experience of working with United in bankruptcy.

All the indications are that the legacy carriers will continue to rationalise their fleets, retiring older smaller narrowbody aircraft, which will create continuing growth opportunities for regional airlines. In other words, FLYi’s views about the future of regional feeder operations are probably not justified. It is indicative that, after being roughly equal in size in 2003 (FLYi with US$731m revenues and SkyWest with US$888m), FLYi (with US$431m projected 2005 revenues) is now less than one third of SkyWest (US$1.5bn) and just one fifth of the SkyWest/ASA combination (US$2.5bn).

SkyWest has an industry–leading liquidity position: June 30 cash reserves of US$557m or about 37% of this year’s revenues. The company is able to fund the ASA purchase from cash reserves, though it will probably opt for a partial debt financing. Long–term debt amounted to US$528.9m at the end of June.

The ASA acquisition, which closed more quickly than had been anticipated, is an important strategic move for SkyWest. The main benefits will be increased size and geographical presence, diversification and access to Atlanta, the world’s largest hub, where ASA holds leases to 26 gates.

The two airlines will have a combined fleet of 372 aircraft, up from SkyWest’s 221, plus 46 orders for delivery through 2007. They will have extensive presence nationwide, with primary hubs in Atlanta, Cincinnati, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Salt Lake City, Denver, Portland and Seattle/Tacoma.

The deal will enable SkyWest to achieve a better balance in ASM production among its two legacy partners — something that was apparently desirable despite Delta’s Chapter 11 risk. The current 35%/65% Delta/United exposure is expected to change to 59%/41% by the end of 2007. The combined fleet includes 62 EMB120s, 229 CRJ200s and 69 CRJ700s, as well as 12 ATR–72s that will be eliminated by the end of 2007. The 46 firm orders are mostly for CRJ700s. In addition, Delta or Comair will lease to SkyWest/ASA 40 additional RJs, of which 22 will be 70- seaters.

As part of the deal, SkyWest’s and ASA’s existing Delta Connection contracts were amended and extended until the end of 2020. Both will continue as fixed–fee agreements, which is the type of contract preferred by all regional airlines. SkyWest appears to have taken great care to structure the deal and formulate its plans so that risks associated with mergers or Chapter 11 are minimised or even eliminated. To avoid the typical merger–related disruptions and hassles, SkyWest has decided to operate the two airlines separately for the foreseeable future. Since SkyWest is totally non–union and ASA is heavily unionised, it makes sense to keep the labour groups separate — there should be no problems particularly since SkyWest’s pay and benefits are at least as good as ASA’s. Nor are there plans to make any significant changes to schedules or aircraft deployment.

Nevertheless, SkyWest expects to achieve some synergies. The plan is to launch an intense "best practices" initiative to utilise the strengths of each airline. Top management positions will obviously not be duplicated — SkyWest’s highly respected management team, led by Jerry Atkin as chairman/CEO, will take over at ASA. The ASA purchase deal was structured so that Delta will have strong financial incentive to affirm the SkyWest and ASA feeder contracts in Chapter 11. When the deal closed, SkyWest only paid Delta US$350 of the US$475m total agreed (US$425 purchase price plus US$50m of returned aircraft deposits); the final US$125m will be paid after four years or if/when Delta affirms the feeder contracts in Chapter 11.

Of course, SkyWest’s position as the leaseholder of 26 ASA gates in Atlanta would make it difficult for Delta to replace it with another carrier. SkyWest’s leadership noted that those gates put it "in a needed position even if Delta files for bankruptcy".

SkyWest also made provisions to avoid the problem that FLYi initially had of getting stuck with aircraft leases when a partner terminates a feeder contract. SkyWest insisted that the 40–aircraft leases that are part of the ASA purchase deal will terminate at the same time as the contract if there is a material breach by Delta.

There is no doubt that SkyWest had an upper hand in the negotiations, which had lasted for six months but were concluded when Delta was truly desperate. In addition to getting its conditions approved, SkyWest got ASA for a bargain price — Delta itself paid US$700m in 1999 for the 80% stake of ASA that it did not already own.

The deal has been generally welcomed on Wall Street, with analysts noting the likely substantial positive impact on SkyWest’s earnings from 2006. However, SkyWest’s shares may remain volatile until Delta affirms the feeder contracts in Chapter 11.