Atlantic Coast Airlines: Goldilocks, a low-cost strategy for 50-seaters

September 2003

Atlantic Coast Airlines, one of the largest regional carriers in the US, recently announced what has to be one of the most intriguing airline strategy changes devised in the post–September 11, 2001 environment. If implemented and successful, Project "Goldilocks" could also have potentially significant impact on the East Coast competitive landscape.

In brief, ACA wants to give up its United Express business, which currently generates 85% of its revenues. It wants to transform itself from a regional fee–for–service provider into a low fare carrier with a large independent hub operation at Washington Dulles. It intends to utilise its 50–seat RJs in smaller markets and to acquire larger narrowbody jets for higher–density and transcontinental routes.

The most striking thing about the proposal is that it would dramatically increase in the risk profile of the business. ACA would be switching from the industry’s safest, most predictable business model (the "fixed–fee" or "fee–per–departure" feeder agreement) to what has to be the riskiest form of existence. Low–fare carriers in the US have had a dismal survival record.

The largest US regional airlines have remained profitable through the current industry slump because of the protections afforded by their fixed–fee contracts, which guarantee at least small profit margins. The airlines collect the same fees regardless of what load factors and fares are.

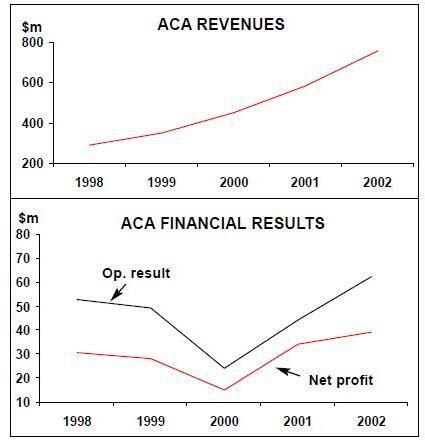

While working with a partner that is in Chapter 11 bankruptcy is obviously not ideal, ACA is still expected to post a healthy pretax profit margin for 2003 similar to last year’s 12%. Of the non–regional carriers, only Southwest and JetBlue have earned better margins than that over the past two years.

The announcement came after months of frustrating negotiations with United, which sought cost cuts and concessions from its regional partners as part of its Chapter 11 restructuring. However, Goldilocks does not appear to be a negotiating ploy; ACA’s leadership firmly believes that the strategy change is in the best interests of shareholders and (barring a hostile takeover) is determined to implement it.

Why, then, would ACA want to make such a controversial switch? Is this further evidence that the low–fare business model will soon dominate the industry? Or has United’s bankruptcy fundamentally changed the attractiveness of the regional business model?

There is considerable interest in ACA’s proposals also because of the potential implications for the rest of the industry. In the first place, ACA is throwing a big spanner in the works of UAL’s reorganisation — how will the major airline cope with the loss of its key partner and RJ provider at Chicago and Dulles?

The possibility of a new low–fare airline emerging to dominate a major East Coast hub is big news indeed. Does ACA have the potential to become Washington DC’s equivalent of JetBlue? Could it inflict serious damage to US Airways' planned RJ operations? Or would the DC–area incumbents (including Southwest at Baltimore) mount strong competitive responses? Not least of all, there is interest in the economics of ACA’s proposed venture. This is believed to be the first time anyone has attempted to be a low fare short–haul carrier with a fleet of RJs, when 150–seater aircraft have tended to be the norm in such operations.

However, there is considerable scepticism about the economics of the proposed venture. If there were doubts about JetBlue doing it with 100- seaters (Aviation Strategy, July/August 2003), how could ACA do it with 50–seaters?

With the economics untested, the investment community has been sharply divided on the plan. Several Wall Street analysts, including Blaylock’s Ray Neidl, JP Morgan’s Jamie Baker and UBS' Robert Ashcroft, have said outright that they believe ACA will be unsuccessful. They are mainly concerned about the RJs' high unit costs, with Baker arguing that "50–seat economics are particularly ill–suited for low–fare operation".

By contrast, Raymond James’ analyst James Parker and Merrill Lynch’s Michael Linenberg have rated ACA’s chances of success as high. Linenberg reminded investors that RJs have substantially lower per–trip costs than larger jets, which makes them optimal for small and medium sized markets. He also noted that the timing could not be better for ACA to utilise its resources in that way, given the weakened financial state of the majors.

Some logistical issues

ACA’s tentative schedule calls for Goldilocks to be launched in the second quarter of 2004.

However, the RJ part of the plan can only materialise if and when United formally rejects ACA’s feeder agreement, which has another seven years to run. This could take place in three ways: when UAL liquidates, when it emerges from Chapter 11 or by mutual agreement between UAL and ACA on how to phase out the aircraft.

United has now officially delayed its planned Chapter 11 exit to the first half of 2004 (meaning late spring or early summer).

Under bankruptcy rules, United has the option of either assuming ACA’s existing contract or rejecting it. It is not likely to assume the contract, because that would mean having to honour all the terms, including higher profit margins and previous RJ growth commitments. The latter may no longer be possible in light of the new growth opportunities granted to SkyWest, Mesa, Air Wisconsin and Trans States as part of new concessionary contracts.

James Parker pointed out in a recent research note that United will have to submit a plan for reorganisation 90 days prior to exiting bankruptcy, and that it will have to state how and when it will replace ACA. Parker suggested that the two sides would most likely agree to a phase–out of RJs and stations beginning in April 2004.

There is obviously a risk that ACA could be stuck with the United contract longer than desired. However, the flip side of that would be that it would continue to earn strong profit margins from the United business, which would help fund the new narrowbody operation. ACA has indicated that it could launch that part of Goldilocks first and fold the RJs in later.

Why this path?

ACA said that Goldilocks was the culmination of an extensive evaluation of different business platforms and changes in the airline industry going back to July 2001. The initial aim was to ensure continued growth opportunities in 2003–2004 and beyond, but after United’s Chapter 11 filing in December 2002 it was also for contingency planning purposes.

In the end, it was a combination of being attracted by the low–fare carrier platform, becoming disillusioned by the fixed–fee model and losing faith in UAL’s long–term prospects.

ACA felt that this was an ideal time to move into the segment of the industry that it believed would succeed in the long term. As CEO Kerry Skeen explained it: "I don’t think anyone will dispute that the low–fare platform is the best place to be, to have earnings and to be able to grow earnings".

ACA also believes that the likely industry consolidation in the next 10 years will have a negative effect on the regionals, specifically in terms of reducing the number of hubs. It has noted a trend in contract talks of the majors playing one regional against another, suggesting continued problems with the major partners.

Regarding the UAL talks, the airline gave a long list of reasons why it could not agree to the terms of a new contract, but in essence it was because of the trend of the fixed–fee economics deteriorating over time. Also, ACA is taking a rather dim view of UAL’s chances of successfully exiting bankruptcy, achieving long–term stability and avoiding labour problems.

Skeen said: "Now that the risk profiles are changing dramatically for that type of business, coupled with a reduction in economic benefit, it is very compelling for us to use CRJs in this manner".

Goldilocks’ business model

The initial Goldilocks business would consist of three elements. First, the airline would operate 87 50–seat CRJ–200s in about 36 low–to–medium density markets from Dulles. They would fly initially 275 departures daily on routes of up to 1,000 miles, with an average trip length of 300–400 miles.

Second, ACA plans to keep its Cincinnati and Boston–based Delta Connection operations, which currently utilise 32 328JETs. It has discussed the matter with Delta and does not foresee problems in the short term at least.

Third, ACA hopes to utilise 130–200 seat narrowbody aircraft in coast–to–coast and other primary markets currently served by United. That fleet would grow from 3–4 aircraft initially (operating 50 daily frequencies) to about 20 within 12–18 months.

The intention is to retire the remaining J–41s when the United service ends. ACA does not anticipate taking any of the 34 CRJs remaining on firm order. The impression gained is that, under the May 2003 CRJ deferral deal with Bombardier, ACA need not take any of the 34 aircraft in the event that it does not sign a new agreement with United.

ACA has said that it would consider other code–share relationships. However, its top executives also concede that the business model does not really support other code–shares because it is designed to be a very simple operation.

In contrast with United, whose objective at Dulles is to get feed to international and key domestic routes, ACA will aim to cater more for local traffic (aiming for a 50/50 mix).

This will require higher frequencies and more attractive scheduling than is currently the case with United, which operates only one daily flight bank at Dulles. Essentially, ACA expects to revert back to the Dulles schedule of eight daily banks that it had before it converted to fixed–fee service with United in 2000.

Like Southwest and JetBlue, ACA hopes to stimulate traffic. It estimates that 75% of its planned connecting markets do not have low–fare service today. It plans to offer 30–40% lower average fares and 60–70% lower unrestricted fares than what is currently available in those markets.

Key strategic advantages

ACA has many prerequisites in place to make Goldilocks a success. First, it has identified good markets that are evidently under–served and overpriced.

Second, it is already an established operation and will have considerable critical mass at Dulles from day one. Third, it has strong cash reserves to tap for start–up funds and to help sustain losses initially.

ACA will enjoy the unique advantage of being able to create almost overnight a formidable presence at Dulles with 87 CRJs. While implementation may be a challenge, scale should aid in the efforts to develop a brand. ACA calculates that, in terms of departures, it will immediately be the largest airline in the DC area, operating 275 daily flights compared to US Airways' 183 and Southwest’s 156.

The ACA executives made the interesting observation that the only US low–fare carriers that have consistently produced double–digit operating margins since 2001 (Southwest and JetBlue) are both the largest carriers in their main cities. By comparison, AirTran and Frontier, which have not produced double–digit margins (though AirTran is beginning to), are only number two carriers in Atlanta and Denver respectively.

The metropolitan DC area is the nation’s fifth largest local traffic market with 42m annual passengers.

Dulles (13m) is the 25th largest local market, which ACA believes is understated because it has never really been stimulated by lower fares; only AirTran and JetBlue are present in a few larger markets, and many people drive to Baltimore for Southwest’s low fares. Also, Dulles has had inferior service levels compared to National and Baltimore.

ACA is making the case that Dulles is geographically the most convenient airport for the vast majority of DC area residents. The intention is to pull the traffic back to Dulles that would have naturally gone there in the first place, rather than provoke US Airways or Southwest by trying to steal their traffic.

Being able to develop the low–fare operation on one’s home turf will be a major strength.

ACA has 46 gates, a maintenance base and other key facilities at Dulles — the sort of infrastructure that would be difficult for a newcomer to replicate. Questions have been raised about ACA’s ability to take over functions such as scheduling, pricing and revenue management, but the leadership points out that it only gave up those activities three years ago when it went 100% fixed fee.

In 1998 and 1999 the company achieved operating margins of 18.1% and 14.1% respectively.

It has been in business for 14 years, and most of the pre–2000 senior management talent is still there.

ACA is hoping that the Goldilocks announcement will deter other potential new entrants from Dulles (among others, Branson was earlier believed to be targeting that airport for his planned US start–up). However, ACA is not worried about new entrants because they could only start with a few aircraft.

According to James Parker, US Airways' current market coverage overlaps 95% of ACA’s planned markets, but Southwest serves only 23% of the city pairs. Head–to–head competition with Southwest and many other low–cost carriers would be limited by the fact that they could not profitably serve ACA’s 50–seat markets with 150- seaters.

The biggest near–term uncertainty is in respect of United’s plans. United has so far insisted that Dulles will remain an important hub in its global network. However, it will have to cover Chicago first.

ACA had a substantial $221m of cash on June 30 and expects $250–265m at the end of June 2004 (assuming continuation of United Express operations until that point). This would make Goldilocks an even better funded venture than JetBlue, which had $140m of seed money.

It would have ample resources to take it through several initial quarters of operating losses. However, it is worth noting that ACA will have the challenge of financing larger aircraft and that its hitherto extremely strong balance sheet is likely to weaken as a result.

Goldilocks’ economics

ACA expects to achieve unit costs of 15–16 cents per ASM with Goldilocks CRJs, which would be substantially below the 22 cents that the major carriers are apparently paying to the regionals (in Parker’s estimates). The regional’s profit margin and differences in utilisation account for much of the gap.

After taking control of the schedule, ACA expects to be able to boost daily RJ utilisation from the current nine to 11 hours. As a result, facility utilisation and labour productivity will also rise. The addition of larger aircraft will provide a further efficiency boost. Goldilocks will rely on web–based reservations and ticket sales. ACA already has competitive pay scales, an extremely productive workforce and not many restrictive work rules.

Skeen said that ACA’s rationale was exactly the same as JetBlue’s was with the recent ERJ- 190 decision — to operate high–frequency service in smaller markets that could not be served profitably with larger aircraft.

For example, a typical Goldilocks market of 350 miles might generate $12,000 a day in local revenues. CRJ’s costs are $2,800 per departure, so ACA could operate 4.3 daily CRJ departures. The addition of $10,000 daily connecting revenues would enable ACA to operate a total of eight daily CRJ departures. By comparison, a 125–seater could profitably operate less than two daily flights in that market.

The key thing to understanding the Goldilocks concept and economics is that ACA’s RJs and competitors' 150–seaters will not generally be present in the same markets. However, ACA’s leadership suggested that in the relatively limited number of head–to–head markets with Southwest, ACA was likely to offer $15–20 higher fares — a difference so small that people would probably just choose the more convenient airport.

Parker, whose company sponsored investor meetings for ACA in Boston and New York in mid- August, suggested in a research note that the unit cost difference between a 737 and a 50–seat RJ on a 224–mile route would be six cents or $13.44 per seat/$19.50 per passenger. Therefore ACA would need to charge $20 more per passenger in average fare to offset the higher CASM.

Parker feels that Goldilocks' biggest risk is on the revenue side of the equation. The higher RJ unit costs will require fares "at the upper end of the low fare range" (again, assuming RJs in head–to head competition with 150–seaters).

In Parker’s best–case scenario, Goldilocks would earn a 15% pretax margin on $945m revenues within 2–3 years of 87 RJs and 20 narrowbodies being fully on stream. In his worst–case scenario, there would no profit within 2–3 years, Goldilocks is shut down and ACA reverts to a revenue sharing agreement under a major airline code at Dulles, which would produce at least a modest profit margin.