KLM: Still searching for a sustainable role

September 2001

KLM continues to search for a sustainable role for itself. Unable to grow to the same mass as Lufthansa, BA or Air France, its has attempted on various occasions to create a new role for itself — through Alcazar, a virtual merger with Alitalia and a junior partnership in an alliance with BA — but all have failed. Where next?

Founded in 1919, KLM is one of the oldest and longest established carriers worldwide. In its early years it built up a strong long–haul network based initially on routes to link the home country with its colonial outposts. However, based in a country of only 15m inhabitants, it had a low level of indigenous traffic demand and had to look abroad to develop the traffic to satisfy the capacity it offered. The Chicago Conference enabled it to develop these routes. It developed its home base of Schiphol airport in Amsterdam as a transit hub and very successfully built a set of services dependent on the sixth freedom rights it could exploit. Having a very low level of natural point–to–point demand and becoming increasingly dependent on transfer traffic resulted in an operation characterised by high load factors and low yields. It happens as a result to have the longest average stage length of any of the European carriers.

KLM has built Amsterdam to be the fourth largest airport hub in Europe after London, Paris and Frankfurt. Always maintaining a commercial managerial mindset, it took advantage of the management incompetencies of its competitors before their respective privatisations and made significant ingress into the natural markets of Lufthansa (in particular the NordWest Rhein region), Air France and BA. Indeed, it can still be said that Amsterdam is London’s third airport as there are more regional connections from UK airports to Amsterdam than to both Heathrow and Gatwick combined.

In a regulated world, KLM performed adequately. The real problems have appeared in earnest since the onset of European deregulation. Niche operations can only last so long.

Financial results

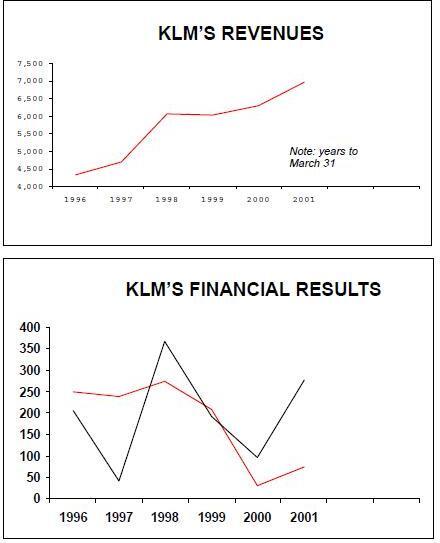

The results for 2000/01 were better than for the previous year but still disappointed the financial markets. On revenues of € 6,960m, up 10%, the company reported doubled operating profits of €277m and net profits of €75m against €29m last time. Traffic in the year grew by 3% against flat capacity. Load factors improved by 1.8 points to 78.5%. Yields rose by 10% in the period, against an increase in units costs of 8% and the break–even load factor fell by 1.3 points to 73.8%.

As a result margins improved by 2.5 points to a mere 4.0%. In the year the group achieved a return on capital of 5.7% up from 3.0% in the prior year. This is at least five points below a sustainable return. Its debt gearing fell marginally to 104% from 107% and interest cover improved to 2.1 times from the death–defying 1.3 times of the previous year.

In the three months to end June 2001, the company announced operating income of only €23m down from €100m in the prior year period. All elements of operations showed significant deterioration: capacity grew by 3% against traffic growth of only 1% (load factors fell by 2 points to 76%); yields fell by 1% against unit cost growth of 4%. As a result margins in the quarter fell by 4.4 points to a mere (break–even level) of 1.3%.

The Wings alliance

KLM’s a long–standing agreement with Northwest on the Atlantic (Wings) involves revenue- and cost–sharing on all routes between the US and Europe, under the auspices of immunity from the US anti–trust laws. In addition, it covers routes to India. Both partners have had bilateral links with other carriers in their own and other regions — but the alliance has not been developed to be as encompassing as either Star or oneworld, and SkyTeam is rapidly developing into a global force.

KLM and Northwest have links with JAS in Japan where their route networks meet at Northwest’s Tokyo hub. It announced in May that it has long last started talking properly with MAS to develop some form of cooperation, although this is unlikely to be fully fledged. Overall, the Wings is a poor third behind Star and oneworld in terms of market presence with only 7% world market share — except insofar that it is the longest established and the furthest developed.

KLM is currently almost inextricably linked with Northwest. The two operators have combined their operations to such an extent that it will be extremely difficult to effect a dissolution. KLM no longer has any sales or marketing activity in the US except where combined with Northwest. Likewise, Northwest uses KLM’s sales and marketing operation in Europe and the Middle/Near east. It has no real US network access except that provided by Northwest.

However, KLM does have an obligation to reimburse Northwest should it renege on the agreement before the end of the11 year contract.

The European merger imperative

Despite some intermediate holding action, the company recognises that it has to combine operations with another European carrier to gain access to a major second hub and to enable it to survive. In particular it needs an entrée into a hub in a major domestic market.

The choices are now minimal. None at this stage in the cycle should now go for the dross in Europe. Alitalia has signed with Air France (and KLM has already been burnt there). Lufthansa (plus SAS and Austrian) is out of the question as is Air France (soon to be linked with Alitalia). Swissair is no longer an option. Starting negotiations with some of the expected fallout from the Swissair experience may be considered — but surely not seriously.

KLM controls roughly 53% (55% including Northwest) of the slots at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport. It is a single terminal airport with currently four runways. A fifth runway is scheduled to open in 2003. The company has suffered considerable opposition from the environmental lobby in the political processes in the Netherlands.

In the past few years it has been constrained on the noise output at the airport — the only airport where such constraints have been imposed. The debate over whether to re–site the country’s main airport in the middle of the North Sea was scotched a year ago — helped by the company’s suggestion that it would move operations out of Holland. The environmental dispute is unlikely to go away. In the short run there appears sufficient capacity, but it is very likely that KLM will become increasingly constrained at its home base.

KLM'’s competitors have discovered the delights of marginal pricing to encourage traffic through their respective hubs — Air France in particular through the development of CDG. KLM has always inherently or surreptitiously had to discount against its competitors' tariffs. In addition, albeit having a good long–haul network, its exposure to the scheduled internal European market is limited to less than a 10% market share.

BA again?

KLM is reported to have reopened negotiations with BA, but they are no longer talking about ensuring a fully merged operation (which would cause problems over the respective route rights and historically has caused disagreements over managerial control) but an agreement which would allow joint European operations and give each access to the second European hub that both require. In time this may lead to joint equity holdings, but in the short run will need to overcome political issues over competition between the UK and Netherlands.

If KLM were to sign a deal with BA, it would presumably bring it under the oneworld banner. This could cause a significant problem with the KLM agreement with Northwest Airlines on the basis that Northwest would suffer political problems were it be seen to be connected to American Airlines. transatlantic deal.

Moreover, BA has discovered a deadline: the EC has pressed its campaign to take control of all bilateral air service negotiations and has put a motion before the European Courts to allow it to do so. As a result the UK government has taken fright and is now earnestly trying to tie up an aviation agreement before Brussels takes power. Consequently, BA is desperately anxious to fulfil some portion of its original agreement with its chosen partner American and has redefined its cooperation agreement with the hope that it is promulgated before the European Court rules in favour of the Commission. Equally, it may be said that the US would want to ratify an agreement before Brussels takes control. BA’s priorities are focussed on the Atlantic and its attention to Europe currently limited.

The painful experiences

In its search for meaningful partnership, KLM’s management have had a lot of bruising experiences in the alliance field. The agreement with Northwest now works very well operationally, but there were bitter boardroom battles between directors of the two airlines over control issues associated with KLM’s 25% shareholding, resulting in the sale of this investment in 1997.

It also had to extricate itself from a misguided investment in Air Littoral. It started negotiations in 1989 with British Airways to form a merged entity to operate a combined "World Airlines" group. This fell apart on questions of control. In the early 1990s it was negotiating with Swissair, SAS and Austrian under the project name of "Alcazar" to create a merged European carrier.

All this having failed it signed a deal with Alitalia in 1997 which was designed to merge the two companies' respective European operations. At the time Alitalia had a deal with Continental and Northwest was negotiating a deal with Continental. The hope was that the four carriers would be able to combine North Atlantic operations to generate a multi–hub trans–regional route system — linking the five US hubs (Minneapolis/St Paul , Detroit, Memphis, Houston, NY Newark) with the three European hubs (Amsterdam, Milan, Rome). For political reasons more than anything else, the Alitalia deal fell apart and Northwest had to dispose of its control in Continental. and now KLM is on its own again. In hindsight it is a great shame that KLM could not pursue its commitment to Alitalia, now lost to the Air France/Delta alliance.

At the same time it took stakes in Braathens SAFE in Norway and Eurowings in Germany to ensure regional links from those areas and attack the incumbent SAS and Lufthansa who had effectively joined operations. These two have now fallen by the wayside as Lufthansa has taken a stake in Eurowings. In addition, KLM was hoping to sell its stake in Braathens to SAS. This deal is now in abeyance following the dismissal of the deal by the Norwegian authorities and is currently stymied by regulatory concerns.

Meanwhile, the company has long had a major (and now fully owned) stake in Air UK, a regional British carrier, which provided substantial feed to Amsterdam from British regional airports. Faced with the start up of low cost competition in the UK from the likes of Ryanair, Easyjet and Go, it rebranded Air UK as a low cost carrier under the soubriquet "Buzz". This has been expensive with estimates of losses last year (to March 2001) reaching €50m. The suggestion is that the company will be forced to close the Buzz brand and move the fleet to its regional subsidiary KLM Cityhopper.

Outlook

If only this industry could get beyond the limitations of the results of the 1944 Chicago Conference the likes of KLM could develop a commercial and economic strategy that would allow it to survive. This should not have anything to do with capital ownership. The failure of the link with Alitalia was due more to political incompetence and interference than anything else — the Italian government just could not work out how to transfer flights from Milan’s overcrowded Linate airport to the new Malpensa without upsetting local politicians and the European Airline community. The delay in the full implementation exhausted KLM’s patience. The company’s talks with BA last year foundered on the problems of maintaining Dutch national route rights and required control of an airline by nationals of the home country for international route rights.

As it is KLM is left with three difficult alternatives:

1. Continue as is, with continued yield, unit revenue and margin erosion as the European majors concentrate on their own base hub development.

2. Yield to BA takeover, forgetting any idea of corporate or national identity. Attempt to disband the Northwest agreement in favour of a potential American Airlines connection. Forfeit management control in order to create the first cross–border European merger.

3. Acquire stakes in the remaining nonaligned airlines in Europe. Maybe even attempt to take over troubled Swissair or take a stake in Sabena or TAP (likelihood of success zero).