Can Air Canada leverage its virtual monopoly?

September 2000

Shareholders in Air Canada have reason to be happy — shares in the airline are up 80% this year. Moreover, the CEO, Robert Milton, has promised shareholders that "as the huge benefits of the [Air Canada/Canadian] restructuring roll in, they will accrue to you." Could Air Canada possibly avoid all the usual dire problems that befall the vast majority of airline mergers? And can it consolidate what is a virtual monopoly and turn short–term returns into a longer–term profit profile?

It now appears that the pilot contract conflict will be resolved through arbitration. So Air Canada will avoid a disastrous strike, and the government will not have to carry out its threat of imposing a solution on the national carrier. Also, as the summer traffic peak winds down, customer service and operations staff will have a period of respite to try and repair the significant customer relationship damage done over the last four or five months. The airline has publicly given itself 180 days to solve all its customer service problems.

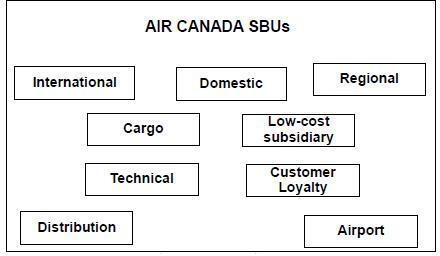

Air Canada has publicly talked about several spin–offs that could be floated as IPOs, so bringing in additional cash while retaining effective decision–making control. These include: Aeroplan, (the customer loyalty unit); a low cost carrier based at Hamilton (near Toronto); the regional airline subsidiaries; a leisure airline, the cargo operation; and the maintenance division. Apart from the obvious financial implications in terms of cash infusions, there are several possible benefits to Air Canada of following this SBU (Strategic Business Unit) strategy which a number of Euro–majors have adopted.

First, creating a separate low cost subsidiary is a good way to match most of the new entrants' products, although whether Air Canada’s component cost structures can be truly segregated is questionable (Continental Lite all over again?). Air Canada now owns the rights to many domestic airline brands, including the former Canadian regionals, and so may be able to exploit local loyalties to dilute the impact of the new entrants. Similarly, the new SBU–based structure may defuse customer dissatisfaction with the airline and head off any government attempts of re–regulate the market and control Air Canada’s pricing policies.

Second, the splintering of Air Canada into various operating and non–operating units should allow for the use of less expensive labour and serve to dilute union influence. Pilots, technical staff and other in–flight staff could be split into several units at different wage rates and on different working conditions.

Third, the main benefit of the Air Canada/Canadian merger was the creation of a single Canadian–based international carrier. The additional leverage on transborder and intercontinental markets is the main reason for the strong financial projections. Isolating the international operations from any domestic market turmoil should allow them to grow impeded only by market growth rate and competitive constraints.

The possible downside of the SBU strategy includes these threats.

- Managerial cost overlap created by having multiple fixed cost bases at each SBU;

- Intra–company cannibalism if the various domestic SBUs compete against each other for the same revenue;

- The cost reduction potential of the SBU being undermined by the new agreement with the pilots which gives them, among other things, protection from lay–offs for four years and restraints on hiring for the new Air Canada units;

- The reaction of other labour groups to the various re–organisations — inter–union cultural issues will, as always, be significant and have the potential to wreak havoc with an already poor customer service record; and

- The IT consequences of supporting all of the Air Canada pieces on one or multiple systems — the power of data acquisition, usage and leverage will play a large role in deciding how many benefits shareholders will see from the merger.

Simultaneous threats

The huge worry is that most or all of these threats will materialise simultaneously in the cyclical downturn that will probably occur in 18 months or so. If international, transborder and domestic markets slow or contract simultaneously then previous downturns have taught us that the bigger the airlines are, the more money they lose. The more pieces of an SBU–based corporation that follow the same cyclical imperatives, the worse the financial damage.

In the depths of the last recession the old Air Canada had no trouble losing C$500–600m/year. Adding in the old Canadian losses easily pushes the total over C$1bn. Assuming that the current Air Canada management can bridge the gap with its claimed C$700m of net cost efficiencies and revenue synergies, then one comes back to a loss figure of C$300-$400m. The acid test of the SBU strategy is whether it can minimise Air Canada’s traditional vulnerability to cyclical shocks. But there is limited evidence to date that substantiates this thesis

There is also the risk of another hostile incursion into the Canadian market by American/Oneworld (some analysts still contend that once Air Canada has cleaned up the messiest bits of its merger re–structuring, it will attract the attentions of an Onex version two). If Air Canada fails to deliver on its "180 days to perfect service" promise, many currently captive customers could be very receptive to alternative, oneworld–linked competitors.

On the transborder front, any merger between US Majors would be a cause for concern — in particular if the merger involves US Airways, which has a lot of Canada–US service. If the United/US Airways proposed merger goes ahead, the pressure would be on Air Canada to prove to United that it would be better off using AC–coded joint services than what it would be using US Airways capacity on transborder sectors. If US Airways links up with any of the other Majors, Air Canada/United duo will be faced with much more formidable competition than they have had to date.

On an intercontinental basis no significant new threats are emerging from either Canadian start–ups or incursions from other international carriers.

This leaves the threat from new entrants in the domestic marketplace. If one takes the fleet and route system projections of the known players including WestJet, Canjet, Royal Air (scheduled), Roots Air, Canada 3000 (scheduled), Air Transat (scheduled) one sees a combined addition of around 35–40 aircraft in the 120–150 seat range 18 months from now. Also, there will probably at least two more new entrants who have not yet announced their intentions. Air Canada itself says it will offload 30–35 DC–9s (ex–Air Canada) and/or 737–200s (ex–Canadian) to the Hamilton start–up carrier.

The implication is that Air Canada will probably lose a 10–15% share of the domestic market but this will not be materially different from the share of market that Air Canada/Canadian combo held in the last downturn. If the new Air Canada can retain at least 75% of domestic share, then its overall network strategy will not be derailed. Also, most of the domestic new entrants will still feed connecting international traffic revenue to Air Canada.

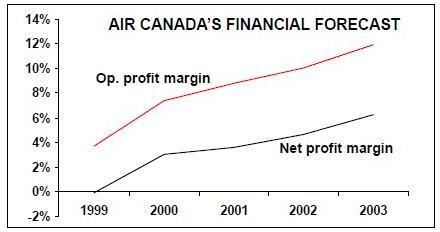

In isolation none of these factors should present any insurmountable obstacles. However, the combination of internal re–structuring, the implementation of the SBU structure, the domestic new entrant threat, and the brand damage caused by poor customer service makes the achievement of Air Canada’s own five–year profit margins projections somewhat questionable.