US Airways: now what's going on?

September 1999

US Airways aims to become a global “carrier of choice” with the help of a new Airbus fleet, MetroJet and other smart strategies. But, just as modest capacity growth has resumed for the first time in five years, costs are surging, yields are tumbling, operating performance is deteriorating and customer complaints are rising. Now that contract talks with the mechanics have broken down, the company faces the nightmarish prospect of a strike after a 30–day “cooling–off” period. At the same time, key shareholders are getting impatient.

All of this turmoil is disappointing in the light of the impressive efforts of the Wolf–Gangwal leadership team. First, a new five–year pilot contract in the autumn of 1997 ended years of stalemate, offered some cost savings and facilitated an order for up to 400 Airbus narrowbody aircraft. The deal also paved the way for the launch of MetroJet in June 1998 and the introduction of regional jets to the fleets of commuter partners.

The past 12 months have seen a complex route network restructuring, as MetroJet and the Boston–New York–Washington Shuttle, which was purchased in late 1997, have been grown rapidly at the expense of the mainline short–haul operations. MetroJet, which already serves 22 cities with a 41–strong fleet, is helping US Airways retain low–fare markets, while Shuttle enhances its presence on the most lucrative business travel routes in the Northeast.

There has also been major transatlantic expansion since 1996. This is logical as the bulk of the US–Europe traffic is destined to or originates from US Airways’ East coast stronghold. Seats offered to Europe have tripled since 1995, and further growth will be facilitated by the introduction of the A330 next year and the new terminal facilities at Philadelphia due to open in 2001.

Feeder operations have been enhanced with the introduction and expanded use of the regional jet by Mesa and Chautauqua Airlines — most recently at New York’s La Guardia — and the growth of turboprop flying by other US Airways Express operators. And US Airways has strengthened its overall market position by forging a marketing and FFP alliance with American in April 1998.

All of this adds up to a smart and balanced expansion strategy, which focuses on strengthening US Airways’ already formidable presence in the Eastern US. And the pace can hardly be considered reckless — just 3.9% overall ASM growth in the first six months of this year, after a 2.7% decline in 1998.

The network restructuring has been accompanied by various cost saving and revenue enhancing measures. The most important ones have been the consolidation of maintenance facilities from six to three, the launch of an improved international business product (Envoy Class) in late 1997, and a 25–year agreement with SABRE last year to provide most the company’s computer needs.

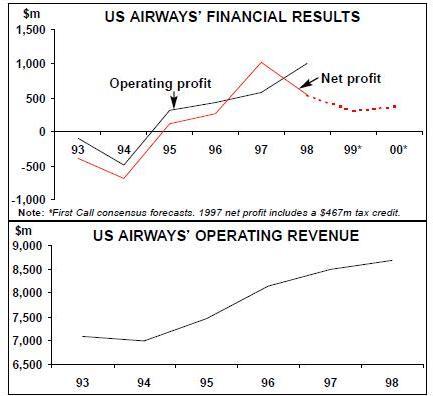

At the same time, US Airways has consolidated its 1995 financial turnaround. For 1998 the Group reported a pre–tax profit of $902m and a net profit of $538m, representing 10.4% and 6.2% of revenues. Total debt was reduced from $2.8bn to $2bn in the three years to the end of 1998, while cash rose from $900m to $1.2bn in the same period. Some $972m of preferred stock has been eliminated and there is a common stock repurchase programme in place to boost shareholder value.

The first indication that something was wrong came in early June 1999, when US Airways warned that its June quarter earnings would be below expectations. That in itself was none too surprising as the May statistics had indicated an industry–wide weakening of domestic traffic growth and yields. But a second warning from US Airways on July 14 that its earnings would remain disappointing through the rest of 1999 set alarm bells ringing.

The Group reported a 25.4% decline in operating profit to $279m in the second quarter. Although net profit rose by 63% to $317m, it included $181m of non–recurring after–tax gains from the sale of securities — without those gains net earnings fell by 30% to $136m.

It was not the worst of the profit declines posted by the Major, but the situation at US Airways is rather troubling for several reasons. First, the carrier appears to be under much greater pressure on the revenue side than the rest of the industry, while its cost trends are also disconcerting. Second, there has been a surge in flight cancellations and passenger complaints. Third, as indicated by two filings to the SEC in August, the problems have got worse as the summer has progressed.

The company does not have a cohesive plan to tackle those issues. As a result, analysts have revised down their estimates of the Group’s earnings for the third and fourth quarters and for the year several times this summer. The latest First Call consensus forecast is a profit of $4.24 per diluted share for 1999, which would represent a 24% decline from last year’s $5.60. The 3Q and 4Q estimates are $1.06 and 88 cents respectively.

However, these forecasts are probably already out of date as news of the breakdown of mechanics’ contract talks at US Airways appears to have prompted another round of earnings revisions. On August 25 PaineWebber analyst Sam Buttrick reduced his estimates to just 60 cents for both 3Q and 4Q, and $3.60 for the year, to reflect weaker revenue generation resulting from lost bookings during a countdown period to a possible strike.

US Airways’ stock has been a dismal performer, falling by as much as 35% in July alone (beating UAL’s 21% and TWA’s 16%). In early August the share price plummeted to a new 52- week low of just over 30 cents, down from a peak of about 80 cents in mid–1998.

Why operational problems?

Since the beginning of this year US Airways has been plagued by an unusually high level of flight cancellations. In the first quarter, 5.6% of its scheduled flights were not completed, which was more than double the level in the same period in 1998 and 1997. The second–quarter figures were nearly as bad, and July saw a cancellation rate of 7.6%, compared to 1.8% a year ago. The company warned in early August that its costs and revenues would continue to be hurt by flight cancellations and passenger dissatisfaction in the third quarter.

The cancellations have been blamed on a host of factors, including the weather (first quarter), ATC delays (particularly bad in July), pilot training issues, the complexity of integrating new Airbus aircraft, the need to reconfigure aircraft for MetroJet, problems in switching to SABRE, and delays in getting aircraft out of scheduled maintenance.

Some of this obviously hints at growing pains — after all, US Airways did take on a formidable challenge in simultaneously executing so many new strategies. However, the real reason for the continued maintenance delays appears to be the difficult situation with the mechanics. The company has not yet publicly admitted this, but all the evidence suggests that there has been a prolonged work slowdown.

This would certainly explain why there is no decisive strategy for dealing with the crisis. One of the recent SEC filings stated that the company is “unable to precisely determine the timing of when these factors will be resolved”. According to a US Airways spokesman, the situation is being controlled primarily with “a small number of preemptive flight cancellations”.

All of that has made it necessary to scale back expansion. The slowing of domestic traffic growth in the spring prompted US Airways to reduce its planned 1999 ASM growth from 7% to 6%. In August that figure was trimmed to 5.1% due to lack of aircraft and demand conditions. US Airways anticipates only 1% RPM growth in 1999, which would lead to a 2.8–point load factor decline.

Serious labour trouble

But those growth rates will, of course, not materialise if the labour situation deteriorates. On August 23 the company’s mechanics, represented by IAM, asked the National Mediation Board (NMB) to declare the contract talks at an impasse. As expected, the NMB released the two sides into a 30–day “cooling–off” period, which will expire on September 25. If no tentative contract is reached by then, the union will be free to strike.

The mechanics have been in contract talks since 1995. Although tentative agreement was reached in early June, in mid–July the membership rejected it with a 75% majority and voted to support a strike. Major issues like pay and job security are the sticking point. The union is seeking retroactive pay to September 1997, an immediate 4% rise, 4% annual rises thereafter and premiums on evening and overtime work.

US Airways has sought to secure concessionary contracts similar to the 1997 pilot deal with its other unions. Its 6,100 fleet service workers — another important IAM–represented group — ratified their first contract in April, while TWU–represented dispatchers followed suit in July. Talks with the 9,500 passenger service employees, who have just elected to be represented by the Communications Workers of America (CWA), may be concluded relatively quickly. However, tough negotiations continue with the flight attendants under federal mediation.

US Airways has a long history of difficulties with its mechanics — each of the past four IAM contract talks dating back to 1982 ended in impasses and the most recent one resulted in a four–day strike in 1992. Although the mechanics’ pay is believed to be close to the industry average, the workers are determined to get their share of the company’s record profits. A strike is, of course, a nightmarish scenario for any carrier, but a 30–day countdown alone can inflict much financial damage. An August 27 SEC filing by US Airways warned of “an adverse effect on short–term revenues”. PaineWebber tentatively estimates (without input from US Airways) that the “booking away” impact of a 30–day countdown could be a revenue loss of around $50–60m.

Yield and unit cost pressures

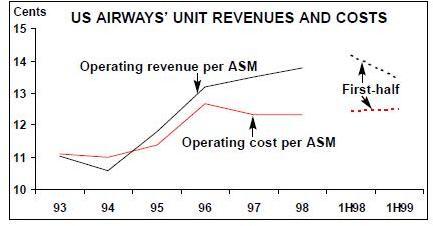

US Airways has been expected to gradually lose its revenue–premium because of growing low–cost competition on the East coast, and the transfer of routes to low–fare MetroJet has naturally accelerated that trend. But no–one expected it to happen this fast. US Airways’ unit revenues fell by 6.2% in the second quarter, which was the sharpest decline reported by the major carriers. According to a recent estimate by Merrill Lynch, July saw an 8% decline, when the average fall of just 0.8% for the rest of the industry reflected improvement over the May and June figures.

This has prompted some criticism from analysts that the financial effects of MetroJet were miscalculated. Perhaps the new venture has been taken to too many business–oriented markets, where the mainline operation previously attracted substantial volumes of premium–fare traffic? However, it is important to bear in mind that US Airways really had no choice other than to get on the low–cost bandwagon and that it needed to defend its key markets.

MetroJet was centred on Baltimore, where Southwest has established a base, and it was taken to the Northeast–Florida markets, where Delta Express has become a major competitor. But possibly the toughest challenge has actually come from United, which in April began aggressively building Washington Dulles into a fully–fledged hub with numerous short–haul, transcontinental and international services. United is now also considering bringing its low–cost Shuttle to Dulles.

The indications are that MetroJet has achieved significant efficiencies with its one aircraft type, single–class, quick turnaround operations. Average daily aircraft utilisation has risen from nine to 12 hours. Load factors have apparently met expectations and a broad–based FFP has helped attract business traffic. However, MetroJet will not have much impact on US Airways’ extremely high overall unit cost structure.

Because of the inevitable decline in unit revenues and yields, US Airways is pinning its hopes on unit cost reduction. Costs per ASM were supposed to start coming down this year with the help of capacity expansion, but that has not happened for several reasons. First, labour costs are rising — in the June quarter that trend was attributed to a decision to grant immediate pay rises to customer service agents. Second, the hike in fuel prices is having a greater impact on US Airways than on its competitors because it is less hedged against fuel costs. Third, there have been additional costs associated with getting new systems working. Fourth, extra spending is bound to be necessary to restore operational performance and service standards.

However, once the current problems have been ironed out, the modern and streamlined Airbus fleet is fully integrated and international expansion gets into full swing, unit costs should start coming down. US Airways is still expected to outperform the industry in terms of unit cost reduction over the next few years.

Fleet and expansion plans

Growth will largely come from MetroJet and transatlantic expansion, though because of the short term aircraft availability constraints MetroJet’s expansion will now slow a little until around the middle of next year. Several new markets planned for this autumn have been cancelled and the venture will now utilise at most 48 aircraft by year–end, compared to the previously envisaged 54.

The process of fully integrating Shuttle continues with the transfer of more routes, revamping the product and upgrading the fleet. US Airways recently converted its own Boston–Washington National and Dulles to Boston and LaGuardia services into Shuttle, and Dallas services will follow shortly. In October Shuttle will receive its first A320, which will replace its 11–strong hush–kitted 727 fleet over the next year.

The A319 and the A320, which entered service last November and February respectively, will ultimately replace also the 737–200, DC9–30 and MD–80 fleets. There are now 25 A319/320s in the fleet, with 14 more scheduled for delivery by year end. The rest of the 87 firm orders and 272 option will arrive at a rate of about 25 aircraft per year. The A330–300, which is expected to enter service in late spring, will replace the transatlantic fleet of 12 767–200s (which will be transferred to longhaul domestic routes) and facilitate major international expansion, as well as a three–class service.

The seven A330–300s on firm order are all due to arrive by early 2001, and the 23 options can be switched to other A330 models or the A340.

There are also ambitious plans on the drawing board for US Airways Express operators. Manufacturers have reportedly been approached for proposals for up to 400 regional jets. But that would require the approval of US Airways’ pilots union, whose current contract caps the number of RJs at 9% of the mainline fleet (about 35). Even though RJs must be particularly threatening to the pilots of a predominantly short–haul carrier, the union is believed to be willing to consider relaxing the restrictions.

Shareholder value considerations

In early August US Airways’ shares received a temporary boost as Tiger Management, a large New York City hedge fund that owns 22.4% of the airline’s stock, said in an SEC filing that it is exploring ways to enhance shareholder value, including options such as a merger, sale or recapitalisation. While praising US Airways’ management, Tiger felt that the stock was undervalued and indicated that it may consider selling its stake.

The announcement may have been intended mainly at stabilising the share price. It is certainly hard to see how US Airways could possibly benefit from another ownership change. A merger with another major carrier would be an unrealistic proposition because of labour and antitrust hurdles. US Airways and American have been talking about expanding their marketing alliance, which could obviously be extremely beneficial. However, the issue may have been relegated to the sidelines this summer as both carriers have had serious internal problems to deal with.